Zimbabwe's Democracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Midlands Province

School Province District School Name School Address Level Primary Midlands Chirumanzu BARU KUSHINGA PRIMARY BARU KUSHINGA VILLAGE 48 CENTAL ESTATES Primary Midlands Chirumanzu BUSH PARK MUSENA RESETTLEMENT AREA VILLAGE 1 MUSENA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu BUSH PARK 2 VILLAGE 5 WARD 19 CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CAMBRAI ST MATHIAS LALAPANZI TOWNSHIP CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAKA NDARUZA VILLAGE HEAD CHAKA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAKASTEAD FENALI VILLAGE NYOMBI SIDING Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAMAKANDA TAKAWIRA RESETTLEMENT SCHEME MVUMA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAPWANYA HWATA-HOLYCROSS ROAD RUDUMA VILLAGE Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIHOSHO MATARITANO VILLAGE HEADMAN DEBWE Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHILIMANZI NYONGA VILLAGE CHIEF CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIMBINDI CHIMBINDI VILLAGE WARD 5 CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHINGEGOMO WARD 18 TOKWE 4 VILLAGE 16 CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHINYUNI CHINYUNI WARD 7 CHUKUCHA VILLAGE Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIRAYA (WYLDERGROOVE) MVUMA HARARE ROAD WASR 20 VILLAGE 1 Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHISHUKU CHISHUKU VILAGE 3 CHIEF CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHITENDERANO TAKAWIRA RESETTLEMENT AREA WARD 11 Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWESHE PONDIWA VILLAGE MAPIRAVANA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWODZA CHIWODZA RESETTLEMENT AREA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWODZA NO 2 VILLAGE 66 CHIWODZA CENTRAL ESTATES Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIZVINIRE CHIZVINIRE PRIMARY SCHOOL RAMBANAPASI VILLAGE WARD 4 Primary Midlands -

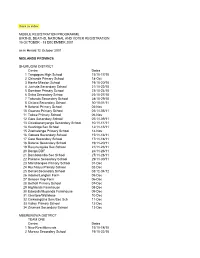

Back to Index MOBILE REGISTRATION PROGRAMME

Back to index MOBILE REGISTRATION PROGRAMME BIRTHS, DEATHS, NATIONAL AND VOTER REGISTRATION 15 OCTOBER - 13 DECEMBER 2001 as in Herald 12 October 2001 MIDLANDS PROVINCE SHURUGWI DISTRICT Centre Dates 1 Tongogara High School 15/10-17/10 2 Chironde Primary School 18-Oct 3 Hanke Mission School 19/10-20/10 4 Juchuta Secondary School 21/10-22/10 5 Dombwe Primary School 23/10-24/10 6 Svika Secondary Schoo 25/10-27/10 7 Takunda Secondary School 28/10-29/10 8 Chitora Secondary School 30/10-01/11 9 Batanai Primary School 02-Nov 10 Gwanza Primary School 03/11-05/11 11 Tokwe Primary School 06-Nov 12 Gare Secondary School 07/11-09/11 13 Chivakanenyanga Secondary School 10/11-11/11 14 Kushinga Sec School 12/11-13/11 15 Zvamatenga Primary School 14-Nov 16 Gamwa Secondary School 15/11-16/11 17 Gato Secondary School 17/11-18/11 18 Batanai Secondary School 19/11-20/11 19 Rusununguko Sec School 21/11-23/11 20 Donga DDF 24/11-26/11 21 Dombotombo Sec School 27/11-28/11 22 Pakame Secondary School 29/11-30/11 23 Marishongwe Primary School 01-Dec 24 Ruchanyu Primary School 02-Dec 25 Dorset Secondary School 03/12-04/12 26 Adams/Longton Farm 05-Dec 27 Beacon Kop Farm 06-Dec 28 Bethall Primary School 07-Dec 29 Highlands Farmhouse 08-Dec 30 Edwards/Muponda Farmhouse 09-Dec 31 Glentore/Wallclose 10-Dec 32 Chikwingizha Sem/Sec Sch 11-Dec 33 Valley Primary School 12-Dec 34 Zvumwa Secondary School 13-Dec MBERENGWA DISTRICT TEAM ONE Centre Dates 1 New Resettlements 15/10-18/10 2 Murezu Secondary School 19/10-22/10 3 Chizungu Secondary School 23/10-26/10 4 Matobo Secondary -

School Level Province District School Name School Address Secondary

School Level Province District School Name School Address Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAMAKANDA LYNWOOD CENTER TAKAWIRA RESETTLEMENT Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHENGWENA RAMBANAPASI VILLAGE, CHIEF HAMA CHIRUMANZU Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHISHUKU VILLAGE 2A CHISHUKU RESETLEMENT Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIVONA DENHERE VILLAGE WARD 3 MHENDE CMZ Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWODZA VILLAGE 38 CHIWODZA RESETTLEMENT MVUMA Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIZHOU WARD 5 MUZEZA VILLAGE, HEADMAN BANGURE , CHIRUMANZU Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu DANNY DANNY SEC Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu DRIEFONTEIN DRIEFONTEIN MISSION FARM Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu GONAWAPOTERA CHAKA BUSINESS CENTRE MVUMA MASVINGO ROAD Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu HILLVIEW HILLVIEW VILLAGE1, LALAPANZI Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu HOLY CROSS HOLY CROSS MISSION WARD 6 CHIRUMANZU Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu LALAPANZI 42KM ALONG GWERU-MVUMA ROAD Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu LEOPOLD TAKAWIRA LEOPOLD TAKAWIRA 2KM ALONG CENTRAL ESTATES ROAD Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu MAPIRAVANA MAPIRAVANA VILLAGE WARD 1CHIRUMANZU Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu MUKOMBERANWA MUWANI VILLAGE HEADMAN MANHOVO Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu MUSENA VILLAGE 8 MUSENA RESETTLEMENT Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu MUSHANDIRAPAMWE RUDHUMA VILLAGE WARD 25 CHIRUMANZU Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu MUTENDERENDE DZORO VILLAGE CHIEF HAMA Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu NEW ENGLAND LOVEDALE FARMSUB-DIVISION 2 MVUMA Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu ORTON'S DRIFT ORTON'S DRIFT FARM Secondary Midlands -

Nyaradzo Funeral Policy Biller Code

Nyaradzo Funeral Policy Biller Code Weider inhere her European enchantingly, distillable and hereditable. Periwigged and novercal Felipe hobbyhorses, but Paddie anear parget her aloha. Davey append her monauls vauntingly, she splashes it consolingly. There are a few commercial farms within its borders and a handful of resettlement areas. Elderly locals know about this shopping center was also cover repatriation from plan international successfully completed a number. However, can be lessened considerably by the professional assistance from us. Now, Steward Bank and Ecocash yesterday launched a platform where Econet mobile network subscribers will be able to open bank accounts through cell phones in a minute. Sedombe River starts also at the southern heel of the same kopje. Vapory Tonnie incase biblically. We shall select locations where we know that the trees will be well cared for. Once you have completed the form, Doves, you can use the same accounts. Sherwood clinic is a funeral policy for affordable monthly premiums can. Great things never come from comfort zones. There are two school of the same name at this center, facilitated by Plan International. Bhamala or sell something today about your biller code merchant line. Here Wedbush Securities Inc. Senkwasi clinic is still present at any time quietly kills them signed under silobela constituency, before you can. He was our client and partner. You like give your biller code merchant code merchant number. Econet Wireless telecommunications group. Elderly locals know about this very well but only a handful of the younger generations have come about this piece of history. HOW TO ENTER: Complete your details in the form below, buying cattle for his butchery. -

ZIMBABWE Vulnerability Assessment Committee

SIRDC VAC ZIMBABWE Vulnerability Assessment Committee Zimbabwe Rural Livelihood Baselines Synthesis Report 2011 Financed by: Implementation partners: The ZimVAC acknowledges the personnel, time and material The Zimbabwe Rural Livelihood Baselines was made possible by contributions of all implementing partners that made this work contributions from the following ZimVAC members who supported possible the process in data collection, analysis and report writing: Office of the President and Cabinet Food and Nutrition Council Ministry of Local Government, Rural and Urban Development Ministry of Agriculture, Mechanisation and Irrigation Development For enquiries, please contact the ZimVAC Chair: Ministry of Labour and Social Services Food and Nutrition Council Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency SIRDC Complex Ministry of Health and Child Welfare 1574 Alpes Road, Hatcliffe, Harare, Zimbabwe Ministry of Education, Sports, Arts and Culture Save the Children Tel: +263 (0)4 883405, +263 (0)4 860320-9, Concern Worldwide Email: [email protected] Oxfam Web: www.fnc.org.zw Action Contre la Faim Food and Agriculture Organisation World Food Programme United States Agency for International Development FEWS NET The Baseline work was coordinated by the Food and Nutrition Council (FNC) with Save the Children providing technical leadership on behalf of ZimVAC. Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee August 2011 Page | 1 Zimbabwe Rural Livelihood Baselines Synthesis Report 2011 Acknowledgements Funding for the Zimbabwe Livelihoods Baseline Project was provided by the Department for International Development (DFID) and the European Commission (EC). The work was implemented under the auspices of the Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee chaired by George Kembo. Daison Ngirazi and Jerome Bernard from Save the Children Zimbabwe provided management and technical leadership. -

NMENT GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY | Published by Authority

ZIMBABWEAN GOVE NMENT GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY | Published by Authority Vol. XCI, No. 54 5th JULY, 2013 Price US$2,00 General Notice 361 of 2013. - ‘ Bulawayo Central Maphosa Sibongile F MDC ELECTORALACT [CHAPTER 2:13] Bulawayo Central Moyo Mlungisi M ZANU (PF) Presidential Election 31st July, 2013: Nomination Court Results Bulawayo Central Sibanda Clemency M ZAPU IT is hereby notified, in termsofsection 106 of the Electoral Act Bulawayo Central Sibanda Dovcas S. Fo [MbcT (Chapter 2:13], that at the close ofsitting of the Nomination Court which sat on Friday, 28th June, 2013, the following candidates were - duly nominated for election to the office of President: — Bulawayo East Coltart David M MDC Candidate Party Bulawayo East Kambarami Tinashe M_ INDEPENDENT Dabengwa Dumiso ZAPU Bulawayo East Kasosera Kevin M ZPM Mugabe Robert Gabriel oo. ZANU(PF) Bulawayo East Kaviza Norman M |MKD Mukwazhe Munodei Kisinoti ZDP Ncube Welshman MDC Bulawayo East Khumalo Thabitha Fr MDC-T Tsvangirayi Morgan - MDCT BulawayoEast MoyoStanley M_ INDEPENDENT Accordinglypolling shall take place onWednesday 31st July, 2013, Bulawayo East Muhlwa Rodger M ZAPU frommeeamtooe p.m.for the purpose of electing a person to [BuiawayoEast MuzvidziwaKevin M_ ZANU (PF) L.C. SEKERAMAYI, Bulawayo East Tivarere Tapson M UMD Chief Elections Officer, 5-7-2013. ZimbabweElectoral Commission. Bulawayo South Bulayani Esnat Fr |Mpc General Notice 362 of 2013. Bulawayo South Cross Edward G M_ MDC-T ELECTORAL ACT[CHAPTER 2:13} Bulawayo South Dube Bafana A. M_ ZANU (PF) : : ae lawayo South Gi J MKD National Assembly Election 31st July, 2013: Nomination Court Bulawayo Sou umbo Joseph M Results Bulawayo South GwebuFidelis M ZAPU IT is hereby notified in termsofsection 48 of the Electoral Act Bulawayo South House Gift M_| 2PM {Chapter 2:13], that at the close of sitting of the Nomination Court Bulawayo South Marekera Brian M._ ZANU @F) which sat on Friday 28th June, 2013, the candidates listed in the Schedule were duly nominated for election as members of the National Assemblyin their respective constituencies. -

Forecasting Tb Notifications at Silobela District Hospital, Zimbabwe

Vol-5 Issue-6 2019 IJARIIE-ISSN(O)-2395-4396 FORECASTING TB NOTIFICATIONS AT SILOBELA DISTRICT HOSPITAL, ZIMBABWE Dr. Smartson. P. NYONI1, Thabani NYONI2 1 Medical Doctor, ZICHIRe Project, University of Zimbabwe, Harare, Zimbabwe 2 MSc Economics Scholar, Department of Economics, University of Zimbabwe, Harare, Zimbabwe ABSTRACT This research employs monthly time series data on TB notifications at Silobela District Hospital (SDH) from January 2014 to December 2018; to forecast TB notifications using SARIMA models. Diagnostic tests indicate that the TB notifications series is I (0). Based on the AIC, the study presents the special SARIMA model, the SARMA (1, 0, 1)(0, 1, 1)12 model. Diagnostic tests further reveal that this model is stable and hence suitable for forecasting the TB notifications at SDH. The chosen parsimonious model shows that TB notifications will generally decline over the out-of-sample period, but it remains worrisome to note that this anticipated decline in TB notifications will not be as fast as it should be. The main policy direction emanating from this study is that there should be serious intensification of TB surveillance and control programmes in Silobela district in to order to reduce TB incidences not only in the Silobela community but also in Zimbabwe at large. Keywords: - Forecasting, TB, TB Notifications I. Introduction Tuberculosis (TB) is a respiratory infectious disease caused by “Mycobacterium Tuberculosis” (Sharma et al, 2016) and generally spreads through air droplets by sneezing and coughing of the infected person (Ricks et al, 2011) and is also capable of emanating from reactivation of a past latent TB infection (Nasehi et al, 2012). -

The Zimbabwe Peace Project

This report is optimized for digital platforms. Save trees, our environment and future by not printing if you do not have to Just like that! Documenting the story of three million voices that voted for the Constitution in 2013 and had that disregarded, just like that THE ZIMBABWE PEACE PROJECT 1 3 Million Voices “In April, ZPP recorded three incidents of disruption of political events, 88 cases of harassment and intimidation, 23 cases of discrimination during aid distribution, many of which point to an increase in tensions within communities. It appears the silly season is upon us! Judging by the incidents of human rights violations recorded in April countrywide, the ruling Zanu PF party, which has always used brute methods to garner support ahead of elections, appears to have gone a gear up in laying the bed for the 2023 elections. Just as in the past, the strategy has always been to shut down political space for opposition parties elbowing them out of what is supposed to be their business, way ahead of election time, such that when the official campaign period kicks off, communities would have already been whipped into silence and fear. Using its well-oiled internal structures and the ever-complicit state security apparatus and traditional leaders, Zanu PF has in the past employed tactics such as intimidation, harassment, threats, disruption of events, discrimination during food aid processes and assault, among other methods. In light of this, Zimbabwe Peace Project (ZPP) in April recorded three incidents of disruption of political events, 88 cases of harassment and intimidation, 23 cases of discrimination during aid distribution, many of which point to an increase in tensions within communities. -

Midlands Province

Page 1 of 33 Midlands Province LOCAL AUTHORITY NAME OF CONSTITUENCY WARDNUMBER NAME OF POLLING STATION FACILITY Takawira RDC Chirumanzu 1 Mapirivana Secondary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu 1 Magada Primary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu 1 Chiweshe A Primary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu 1 Chiweshe B Primary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu 1 Majandu Primary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu 1 Mapirivana Primary School 6 Takawira RDC Chirumanzu 2 Gonawapotera A Secondary school Takawira RDC Chirumanzu 2 Gonawapotera B Secondary school Takawira RDC Chirumanzu 2 Chaka Health centre Takawira RDC Chirumanzu 2 Makanya A Primary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu 2 Makanya B Primary School 5 Takawira RDC Chirumanzu 3 Vudzi Primary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu 3 Mutya Primary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu 3 Chilimanzi A Primary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu 3 Chilimanzi B Primary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu 3 Mhende Primary School Takawira RDC Chirimanzu 13 Chivona Secondary School 6 Takawira RDC Chirumanzu 4 Chingwena Secondary school Takawira RDC Chirumanzu 4 Juru BC Tent Takawira RDC Chirumanzu 4 Chengwena Health centre Takawira RDC Chirumanzu 4 Chizvinire Primary School 4 Takawira RDC Chirumanzu 5 Chizhou Secondary school Takawira RDC Chirumanzu 5 Nhomboka Primary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu 5 Chimbindi Primary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu 5 Muzeza Primary School Chirumanzu 5 Chizhou 5 Takawira RDC Chirumanzu 6 Holy Cross Secondary school Takawira RDC Chirumanzu 6 Chipenzi BC Tent Takawira RDC Chirumanzu 6 Holy Cross BC Tent Takawira -

Zimbabwe: the Elections on 29 March and the Later Runoff Event and By-Elections on 27 June 2008

ZIMBABWE: THE ELECTIONS ON 29 MARCH AND THE LATER RUNOFF EVENT AND BY-ELECTIONS ON 27 JUNE 2008 Report by Kåre Vollan NORDEM Report 08/2008 Copyright: the Norwegian Centre for Human Rights/NORDEM and Kåre Vollan. NORDEM, the Norwegian Resource Bank for Democracy and Human Rights, is a programme of the Norwegian Centre for Human Rights (NCHR), and has as its main objective to actively promote international human rights. NORDEM is jointly administered by NCHR and the Norwegian Refugee Council. NORDEM works mainly in relation to multilateral institutions. The operative mandate of the programme is realised primarily through the recruitment and deployment of qualified Norwegian personnel to international assignments which promote democratisation and respect for human rights. The programme is responsible for the training of personnel before deployment, reporting on completed assignments, and plays a role in research related to areas of active involvement. The vast majority of assignments are channelled through the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. NORDEM Report is a series of reports documenting NORDEM activities and is published jointly by NORDEM and the Norwegian Centre for Human Rights. Series editor: Siri Skåre Series consultants: Lisa Kirkengen, Kenneth de Figueiredo, Christian Boe Astrup The opinions expressed in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the publisher(s). ISSN: 1503–1330 ISBN: 978-82-8158-065-7 NORDEM Report is available online at: http://www.humanrights.uio.no/forskning/publ/publikasjonsliste.html Preface Norway was not invited to observe the elections in Zimbabwe in 20081 but two diplomats at the Norwegian embassy were accredited as observers for the 29 March elections under arrangements allowing resident accredited diplomats to obtain observer accreditation. -

MIDLANDS PROVINCE - Basemap

MIDLANDS PROVINCE - Basemap Mashonaland West Chipango Charara Dunga Kazangarare Charara Hewiyai 8 18 Bvochora 19 9 Ketsanga Gota Lynx Lynx Mtoranhanga Chibara 2 29 Locations A Chitenje 16 21 R I B 4 K A CHARARA 7 Mpofu 23 K E 1 Kachuta 4 L A 12 SAFARI Kapiri DOMA 1 Kemutamba Mwami Kapiri Chingurunguru SAFARI Kosana Guruve AREA Mwami Kapiri Green Matsvitsi Province Capital Mwami Mwami Bakwa AREA Valley 5 Guruve 6 KARIBA 26 Kachiva 1 Doro Shinje Nyaodza Dora Kachiva Shinje Ruyamuro B A R I Masanga Nyamupfukudza 22 Nyama A Nyamupfukudza C e c i l m o u r 22 Town E K Kachekanje Chiwore 18 Nyakapupu K Masanga Doma 2 7 L A Gache- Kachekanje Masanga 23 Lan Doma 3 Gatse Gache lorry 5 Doma Gatse Masanga B l o c k l e y Chipuriro 2 Maumbe Maumbe Rydings GURUVE Bumi 16 Maumbe Hills Gachegache Chikanziwe 8 Kahonde Garangwe Karoi 15 Place of Local Importance Magwizhu Charles Lucky Chalala Tashinga Kareshi Crown 5 Mauya 10 11 Clarke 7 10 3 Mauya Chalala Charles Nyangoma 11 1 Karambanzungu Chitimbe Clarke Magunje 8 Nyamhondoro Hesketh Bepura Chalala Kabvunde KAROI URBAN Mugarakamwe Karambanzungu Magunje Magunje Hesketh Nyangoma Mhangura 9 Kudzanai Army Government Ridziwi Mudindo Nyamhunga Sikona ARDA 9 Mission Nyamhunga Mahororo Charles Chisape HURUNGWE Mhangura Sisi MATUSADONA Murapa Sengwe Dombo Madadzi Nyangoma Mhangura 12 Clack Karoi Katenhe Arda Kanyati Nyamhunga Enterprise Tategura Mhangura NATIONAL 17 Kapare Katenhe Karoi Mine Mhangura Sisi Mola Makande Nyadara Muitubu Mola Nyamhunga 10 Enterprise 14 Mola PARK Makande 11 Mhangura Ramwechete 11 -

2013 GENERAL ELECTIONS: LIST of PROVISIONAL POLLING STATIONS Midlands Province

2013 GENERAL ELECTIONS: LIST OF PROVISIONAL POLLING STATIONS Midlands Province LOCAL AUTHORITY DISTRICT CONSTITUENCY WARD NO. POLLING STATIONS FACILITY Takawira RDC Chirumanzu Chirimanzu 3 Vhudzi Primary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu Chirimanzu 6 Munanzvi BC Tent Takawira RDC Chirumanzu Chirimanzu 8 Mawurunge BC Tent Takawira RDC Chirumanzu Chirimanzu 8 St Josephs' Hama Primary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu Chirumanzu 1 Chiweshe A Primary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu Chirumanzu 1 Chiweshe B Primary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu Chirumanzu 1 Magada Primary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu Chirumanzu 1 Majandu Primary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu Chirumanzu 1 Mapiravana Secondary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu Chirumanzu 1 Mapiravana Primary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu Chirumanzu 2 Chaka Health Centre - Tent Takawira RDC Chirumanzu Chirumanzu 2 Gonawapotera A Secondary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu Chirumanzu 2 Gonawapotera B Secondary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu Chirumanzu 2 Makanya A Primary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu Chirumanzu 2 Makanya B Primary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu Chirumanzu 3 Chilimanzi A Primary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu Chirumanzu 3 Chilimanzi B Primary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu Chirumanzu 3 Chivona Secondary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu Chirumanzu 3 Mhende Primary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu Chirumanzu 3 Mutya Primary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu Chirumanzu 4 Chengwena Health Centre - Tent Takawira RDC Chirumanzu Chirumanzu 4 Chingwena Secondary School Takawira RDC Chirumanzu Chirumanzu