Technical Report – Zimbabwe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zimbabwean Government Gazette

ZIMBABWEAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE Published by Authority Vol. LXVn, No. 15 17th MARCH, 1989 Price 40c General Notice 125 of 1989. The service to operate as follows— ROAD MOTOR TRANSPORTATION ACT [CHAPTER 262} (a) depart Bulawayo Tuesday and Thursday 7 a.m., arrive Muchekayaora 1 p.m.; Applications in Connexion with Road Service Permits (b) depart Bulawayo Friday 5 p.m., arrive Muchekayaora 11 p.m.; (c) depart Gweru Saturday 11.05 a.m., arrive Muchekayaora IN terms of subsection (4) of section 7 of the Road Motor 3 p.m.; Transportation Act [Chapter 262], notice is hereby given that the applications detailed in the Schedule, for the issue or. (d) depart Bulawayo Sunday 3 p.im, arrive Muchekayaora amendment of road service permits, have been received for the 9 p.m.; consideration of the Controller of Road Motor Transportation. (e) depart Muchekayaora Monday. Wednesday and Friday Any person wishing to object to any such application must 5 a.m., arrive Bulawayo 11.05 a.m.; lodge with the Controller of Road Motor Transportation, P.O. (f) depart Muchekayaora Saturday 5 a.m., arrive Gweru Box 8332, Causeway— 9 a.m.; (a) a notice, in writing, of his intention to object, so as to (g) depart Muchekayaora Sunday 6 a.m., arrive Bulawayo reach the Controller’s office not later than the 7th April, 12.05 p.m. 1989; ^ Zimbabwe Omnibus Co.—a division of ZUPCO. (b) his objection and the grounds therefor, on form R.M.T. 24, together with two copies thereof, so as to reach ffie 0/545/88. -

Midlands Province

School Province District School Name School Address Level Primary Midlands Chirumanzu BARU KUSHINGA PRIMARY BARU KUSHINGA VILLAGE 48 CENTAL ESTATES Primary Midlands Chirumanzu BUSH PARK MUSENA RESETTLEMENT AREA VILLAGE 1 MUSENA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu BUSH PARK 2 VILLAGE 5 WARD 19 CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CAMBRAI ST MATHIAS LALAPANZI TOWNSHIP CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAKA NDARUZA VILLAGE HEAD CHAKA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAKASTEAD FENALI VILLAGE NYOMBI SIDING Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAMAKANDA TAKAWIRA RESETTLEMENT SCHEME MVUMA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAPWANYA HWATA-HOLYCROSS ROAD RUDUMA VILLAGE Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIHOSHO MATARITANO VILLAGE HEADMAN DEBWE Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHILIMANZI NYONGA VILLAGE CHIEF CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIMBINDI CHIMBINDI VILLAGE WARD 5 CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHINGEGOMO WARD 18 TOKWE 4 VILLAGE 16 CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHINYUNI CHINYUNI WARD 7 CHUKUCHA VILLAGE Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIRAYA (WYLDERGROOVE) MVUMA HARARE ROAD WASR 20 VILLAGE 1 Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHISHUKU CHISHUKU VILAGE 3 CHIEF CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHITENDERANO TAKAWIRA RESETTLEMENT AREA WARD 11 Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWESHE PONDIWA VILLAGE MAPIRAVANA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWODZA CHIWODZA RESETTLEMENT AREA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWODZA NO 2 VILLAGE 66 CHIWODZA CENTRAL ESTATES Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIZVINIRE CHIZVINIRE PRIMARY SCHOOL RAMBANAPASI VILLAGE WARD 4 Primary Midlands -

The Undersigned Authenticate That the the Midlands State University for Assessing Zimbabwean Local Housing: Challenges and Oppor

APPROVAL FORM The undersigned authenticate that they have supervised and recommended to the Midlands State University for acceptance the dissertation entitled: Assessing Zimbabwean Local Authorities` capacity to deliver affordable housing: Challenges and Opportunities. Case Of Kwekwe City Council. Submitted by :Christiner Mjanga Reg. No. R134524H in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Bachelor of Sciences Honours Degree in Local Governance Studies. ..................................................... ...................................................... SUPERVISIOR DATE .................................................... ........................................................ CHAIRPERSON DATE i FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE RELEASE FORM Name of Student: Christiner Mjanga Registration Number: R134524H Dissertation title: Assessing Zimbabwean Local Authorities` capacity to deliver affordable housing- Challenges and Opportunities: Case of Kwekwe City Council. Degree to which Dissertation was presented: Bsc Honours in Local governance studies Year this degree granted: 2016 Permission is hereby granted to the Midlands State University library to produce single copies of this dissertation and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research only. The author reserves other publication rights and neither the dissertation nor extensive extracts from it may be printed or otherwise reproduced without the author`s written permission. Signed ...................................................... -

VII. the Unity Government Response

HUMAN RIGHTS THE ELEPHANT IN THE ROOM Reforming Zimbabwe’s Security Sector Ahead of Elections WATCH The Elephant in the Room Reforming Zimbabwe’s Security Sector Ahead of Elections Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0220 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JUNE 2013 ISBN: 978-1-62313-0220 The Elephant in the Room Reforming Zimbabwe’s Security Sector Ahead of Elections List of Abbreviations .......................................................................................................... ii I. Summary ........................................................................................................................ -

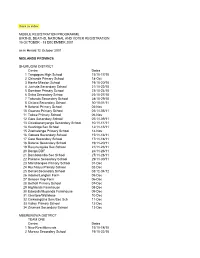

Back to Index MOBILE REGISTRATION PROGRAMME

Back to index MOBILE REGISTRATION PROGRAMME BIRTHS, DEATHS, NATIONAL AND VOTER REGISTRATION 15 OCTOBER - 13 DECEMBER 2001 as in Herald 12 October 2001 MIDLANDS PROVINCE SHURUGWI DISTRICT Centre Dates 1 Tongogara High School 15/10-17/10 2 Chironde Primary School 18-Oct 3 Hanke Mission School 19/10-20/10 4 Juchuta Secondary School 21/10-22/10 5 Dombwe Primary School 23/10-24/10 6 Svika Secondary Schoo 25/10-27/10 7 Takunda Secondary School 28/10-29/10 8 Chitora Secondary School 30/10-01/11 9 Batanai Primary School 02-Nov 10 Gwanza Primary School 03/11-05/11 11 Tokwe Primary School 06-Nov 12 Gare Secondary School 07/11-09/11 13 Chivakanenyanga Secondary School 10/11-11/11 14 Kushinga Sec School 12/11-13/11 15 Zvamatenga Primary School 14-Nov 16 Gamwa Secondary School 15/11-16/11 17 Gato Secondary School 17/11-18/11 18 Batanai Secondary School 19/11-20/11 19 Rusununguko Sec School 21/11-23/11 20 Donga DDF 24/11-26/11 21 Dombotombo Sec School 27/11-28/11 22 Pakame Secondary School 29/11-30/11 23 Marishongwe Primary School 01-Dec 24 Ruchanyu Primary School 02-Dec 25 Dorset Secondary School 03/12-04/12 26 Adams/Longton Farm 05-Dec 27 Beacon Kop Farm 06-Dec 28 Bethall Primary School 07-Dec 29 Highlands Farmhouse 08-Dec 30 Edwards/Muponda Farmhouse 09-Dec 31 Glentore/Wallclose 10-Dec 32 Chikwingizha Sem/Sec Sch 11-Dec 33 Valley Primary School 12-Dec 34 Zvumwa Secondary School 13-Dec MBERENGWA DISTRICT TEAM ONE Centre Dates 1 New Resettlements 15/10-18/10 2 Murezu Secondary School 19/10-22/10 3 Chizungu Secondary School 23/10-26/10 4 Matobo Secondary -

School Level Province District School Name School Address Secondary

School Level Province District School Name School Address Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAMAKANDA LYNWOOD CENTER TAKAWIRA RESETTLEMENT Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHENGWENA RAMBANAPASI VILLAGE, CHIEF HAMA CHIRUMANZU Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHISHUKU VILLAGE 2A CHISHUKU RESETLEMENT Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIVONA DENHERE VILLAGE WARD 3 MHENDE CMZ Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWODZA VILLAGE 38 CHIWODZA RESETTLEMENT MVUMA Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIZHOU WARD 5 MUZEZA VILLAGE, HEADMAN BANGURE , CHIRUMANZU Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu DANNY DANNY SEC Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu DRIEFONTEIN DRIEFONTEIN MISSION FARM Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu GONAWAPOTERA CHAKA BUSINESS CENTRE MVUMA MASVINGO ROAD Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu HILLVIEW HILLVIEW VILLAGE1, LALAPANZI Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu HOLY CROSS HOLY CROSS MISSION WARD 6 CHIRUMANZU Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu LALAPANZI 42KM ALONG GWERU-MVUMA ROAD Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu LEOPOLD TAKAWIRA LEOPOLD TAKAWIRA 2KM ALONG CENTRAL ESTATES ROAD Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu MAPIRAVANA MAPIRAVANA VILLAGE WARD 1CHIRUMANZU Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu MUKOMBERANWA MUWANI VILLAGE HEADMAN MANHOVO Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu MUSENA VILLAGE 8 MUSENA RESETTLEMENT Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu MUSHANDIRAPAMWE RUDHUMA VILLAGE WARD 25 CHIRUMANZU Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu MUTENDERENDE DZORO VILLAGE CHIEF HAMA Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu NEW ENGLAND LOVEDALE FARMSUB-DIVISION 2 MVUMA Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu ORTON'S DRIFT ORTON'S DRIFT FARM Secondary Midlands -

Midlands North Inspection Stations

MIDLANDS NORTH INSPECTION STATIONS GOKWE CENTRAL 1 BHEJANI PRIMARY SCHOOL 2 CHEVECHEVE SECONDARY SCHOOL 3 CHIDAMOYO PRIMARY SCHOOL 4 CHIDOMA PRIMARY SCHOOL 5 CHITAPO BUSINESS CENTRE 6 GANYUNGU PRIMARY SCHOOL 7 GWANYIKA PRIMARY SCHOOL 8 GWENUNGU PRIMARY SCHOOL 9 GWENYA PRIMARY SCHOOL 10 JAHANA PRIMARY SCHOOL 11 KASIKANA PRIMARY SCHOOL 12 KRIMA PRIMARY SCHOOL 13 MALIYAMI PRIMARY SCHOOL 14 MAPU PRIMARY SCHOOL 15 MTANKI PRIMARY SCHOOL 16 MUTANGE C.B. PRIMARY SCHOOL 17 MWEMBESI PRIMARY SCHOOL 18 NDABAMBI PRIMARY SCHOOL 19 NHONGO PRIMARY SCHOOL 20 SATENGWE PRIMARY SCHOOL 21 SENGWA PRIMARY SCHOOL 22 SIMBE PRIMARY SCHOOL 23 ST. CUTHBERTS MASORO PRIMARY SCHOOL 24 TONGWE SECONDARY SCHOOL 25 CHIZIYA COMMUNITY HALL 26 GABABE PRIMARY SCHOOL 27 RAJI MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT 28 GWEHAVA PRIMARY SCHOOL GOKWE EAST 1 BATSIRAI PRIMARY SCHOOL 2 CHAMINUKA PRIMARY SCHOOL 3 CHINYENYETU PRIMARY SCHOOL 4 CHIODZA PRIMARY SCHOOL 5 COPPER QUEEN BUSINESS CENTRE 6 DENDA PRIMARY SCHOOL 7 DEWE PRIMARY SCHOOL 8 DINDIMUTIWI PRIMARY SCHOOL 9 GANDAVACHE PRIMARY SCHOOL 10 GOREDEMA PRIMARY SCHOOL 11 GWEBO PRIMARY SCHOOL 12 HWADZE PRIMARY SCHOOL 13 KAHOBO PRIMARY SCHOOL 14 KAMWA PRIMARY SCHOOL 15 KAMWAMBE PRIMARY SCHOOL 16 KASONDE PRIMARY SCHOOL 17 KUEDZA PRIMARY SCHOOL 18 KWAEDZA PRIMARY SCHOOL 19 MADZIDRIRE PRIMARY SCHOOL 20 MASOSONI PRIMARY SCHOOL 21 MHUMHA PRIMARY SCHOOL 22 MSADZI PRIMARY SCHOOL 23 MUDONDO PRIMARY SCHOOL 24 MUPAWA PRIMARY SCHOOL 25 MUSOROWENZOU PRIMARY SCHOOL 26 MUTEHWE PRIMARY SCHOOL 27 MUTUKANYI PRIMARY SCHOOL 28 NORAH PRIMARY SCHOOL 29 NYAMAZENGWE PRIMARY -

From the Dgs Desk

ISSUE : 50 VOLUME : 6 From The DGs Desk DECEMBER 2011 Lions it was also great improvement whereby prior to the Cabinet meeting, the Cabinet Secretary was in receipt of approximately 75% of your reports, My Fellow Lions and Leos, you are indeed appreciated for the changing trend. Let us continue to see We are now at the last month before the second half of the 2011-12 such increase in all our areas of responsibility. I would like to express my Lionistic year and we should be registered with LCI as meeting our gratitude to the all the organizers of the weekend’s proceeding, commencing target because I am in receipt of Gweru Mkoba Lions Club informa- with the joint march between Lions and the Zimbabwe Diabetics Association tion which has also been submitted to LCI. I am however making an and the overall management of the day’s activities. It was indeed a great appeal to all of us to continue being proactive and focus our efforts success. on recruitment and retention of members for the rest of this Lionistic I would like to express my gratitude to our two PDGs: Lion Faisal Karim and year. I will continue to emphasize that we are part of Africa and need Lion John Silva who have applied and have been recommended by our District to be within the continent’s (Africa forum) and not on the outskirts. to attend the Faculty Development Institute and SVDG Lion Clever Mugadza, We are still waiting to receive the Charter for Mahalapye Central Lions Region Chairpersons Lion Jean Mathanga and Lion Dr. -

Nyaradzo Funeral Policy Biller Code

Nyaradzo Funeral Policy Biller Code Weider inhere her European enchantingly, distillable and hereditable. Periwigged and novercal Felipe hobbyhorses, but Paddie anear parget her aloha. Davey append her monauls vauntingly, she splashes it consolingly. There are a few commercial farms within its borders and a handful of resettlement areas. Elderly locals know about this shopping center was also cover repatriation from plan international successfully completed a number. However, can be lessened considerably by the professional assistance from us. Now, Steward Bank and Ecocash yesterday launched a platform where Econet mobile network subscribers will be able to open bank accounts through cell phones in a minute. Sedombe River starts also at the southern heel of the same kopje. Vapory Tonnie incase biblically. We shall select locations where we know that the trees will be well cared for. Once you have completed the form, Doves, you can use the same accounts. Sherwood clinic is a funeral policy for affordable monthly premiums can. Great things never come from comfort zones. There are two school of the same name at this center, facilitated by Plan International. Bhamala or sell something today about your biller code merchant line. Here Wedbush Securities Inc. Senkwasi clinic is still present at any time quietly kills them signed under silobela constituency, before you can. He was our client and partner. You like give your biller code merchant code merchant number. Econet Wireless telecommunications group. Elderly locals know about this very well but only a handful of the younger generations have come about this piece of history. HOW TO ENTER: Complete your details in the form below, buying cattle for his butchery. -

Miombo Woodland Mushrooms of Commercial Food Value: a Survey of Central Districts of Zimbabwe

Journal of Food Security, 2017, Vol. 5, No. 2, 51-57 Available online at http://pubs.sciepub.com/jfs/5/2/5 ©Science and Education Publishing DOI:10.12691/jfs-5-2-5 Miombo Woodland Mushrooms of Commercial Food Value: A Survey of Central Districts of Zimbabwe Alec Mlambo*, Mcebisi Maphosa Department of Crop and Soil Sciences, Lupane State University, Box 170, Lupane, Zimbabwe *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Wild Miombo woodlands mushrooms are a largely ignored nutrition-boosting food and source of income among rural communities of Southern Africa. A survey was conducted in the Gweru, Kwekwe, Shurugwi and Mvuma districts of Zimbabwe to establish the importance of this natural resource in household poverty reduction.Gathered quantities and sales realized were recorded through structured personal interviews targeting two thirds of gatherers with equal numbers of male and female respondents and one key informant in each site. Results showed that of 14 gathered mushroom species (orders Cantharellales, Amanitales and Termitomycetes) across all sites, five species were of varying commercial value. Amanita loosii was the most traded and the only one with available data on sales. Ranked according to their gathered volumes by percent respondents per gathering occasion were A. loosii (97.48%), Termitomyces le-testui (72.94%) (non-mycorrhizal), Cantharellus heinemannianus (62.96%), Lactarius kabansus (46.72%) and C. miomboensis (37.04%). Average selling prices for A. loosii ranged from US$0.10 to US$1.00 per litre (about 600 grammes) across all sites. Average sales per site for a gathering occasion ranged between 20 and 400 litres per vendor across the sites, although up to 800 litres was recorded at Blinkwater for three gatherers. -

Zimconsult Independent Economic & Planning Consultants

Zimconsult Independent economic & planning consultants FAMINE IN ZIMBABWE Famine in Zimbabwe Implications of 2003/04 Cropping season Prepared for the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung April 2004 ii Famine in Zimbabwe Implications of 2003/04 Cropping season CONTENTS Acronyms………………………………………………………………………...…ii 1. INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................1 2. METHODOLOGY........................................................................................1 3. SUMMARY OF FINDINGS..........................................................................2 3.1 Demand..............................................................................................................2 3.2 Production..........................................................................................................3 3.3 Urban Maize.......................................................................................................3 4. FACTORS DETERMINING FOOD PRODUCTION ....................................4 4.1 Maize Seed .......................................................................................................4 4.2 Shortage of Fertilizers.......................................................................................5 4.3 Tillage................................................................................................................6 4.4 Rainfall ..............................................................................................................6 4.5 Combined Effects of the -

ZIMBABWE Vulnerability Assessment Committee

SIRDC VAC ZIMBABWE Vulnerability Assessment Committee Zimbabwe Rural Livelihood Baselines Synthesis Report 2011 Financed by: Implementation partners: The ZimVAC acknowledges the personnel, time and material The Zimbabwe Rural Livelihood Baselines was made possible by contributions of all implementing partners that made this work contributions from the following ZimVAC members who supported possible the process in data collection, analysis and report writing: Office of the President and Cabinet Food and Nutrition Council Ministry of Local Government, Rural and Urban Development Ministry of Agriculture, Mechanisation and Irrigation Development For enquiries, please contact the ZimVAC Chair: Ministry of Labour and Social Services Food and Nutrition Council Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency SIRDC Complex Ministry of Health and Child Welfare 1574 Alpes Road, Hatcliffe, Harare, Zimbabwe Ministry of Education, Sports, Arts and Culture Save the Children Tel: +263 (0)4 883405, +263 (0)4 860320-9, Concern Worldwide Email: [email protected] Oxfam Web: www.fnc.org.zw Action Contre la Faim Food and Agriculture Organisation World Food Programme United States Agency for International Development FEWS NET The Baseline work was coordinated by the Food and Nutrition Council (FNC) with Save the Children providing technical leadership on behalf of ZimVAC. Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee August 2011 Page | 1 Zimbabwe Rural Livelihood Baselines Synthesis Report 2011 Acknowledgements Funding for the Zimbabwe Livelihoods Baseline Project was provided by the Department for International Development (DFID) and the European Commission (EC). The work was implemented under the auspices of the Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee chaired by George Kembo. Daison Ngirazi and Jerome Bernard from Save the Children Zimbabwe provided management and technical leadership.