Seafood Risk Assessment New Zealand Blue Cod Fishery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marine Fish Conservation Global Evidence for the Effects of Selected Interventions

Marine Fish Conservation Global evidence for the effects of selected interventions Natasha Taylor, Leo J. Clarke, Khatija Alliji, Chris Barrett, Rosslyn McIntyre, Rebecca0 K. Smith & William J. Sutherland CONSERVATION EVIDENCE SERIES SYNOPSES Marine Fish Conservation Global evidence for the effects of selected interventions Natasha Taylor, Leo J. Clarke, Khatija Alliji, Chris Barrett, Rosslyn McIntyre, Rebecca K. Smith and William J. Sutherland Conservation Evidence Series Synopses 1 Copyright © 2021 William J. Sutherland This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Taylor, N., Clarke, L.J., Alliji, K., Barrett, C., McIntyre, R., Smith, R.K., and Sutherland, W.J. (2021) Marine Fish Conservation: Global Evidence for the Effects of Selected Interventions. Synopses of Conservation Evidence Series. University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. Further details about CC BY licenses are available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Cover image: Circling fish in the waters of the Halmahera Sea (Pacific Ocean) off the Raja Ampat Islands, Indonesia, by Leslie Burkhalter. Digital material and resources associated with this synopsis are available at https://www.conservationevidence.com/ -

Yellow-Eyed Penguin Diet and Indirect Effects

CSP16205-1 POP2016-05 Mattern & Ellenberg - Yellow-eyed penguin diet and indirect effects 1 CSP16205-1 POP2016-05 Mattern & Ellenberg - Yellow-eyed penguin diet and indirect effects Table of Contents Abstract ....................................................................................................3 Introduction .............................................................................................4 Background/context ............................................................................................ 4 Objectives ........................................................................................................... 5 Methods ....................................................................................................5 Results ......................................................................................................6 Main prey species, inter-decadal & regional variations ...................................... 6 Prey sizes, age classes & temporal occurrence .................................................. 11 Differences between adult & juvenile penguins ............................................... 13 Prey behaviour & capture strategies ................................................................. 13 Prey association with benthic sediments .......................................................... 14 Indirect fisheries effects on prey composition and behaviour ........................... 17 Linear foraging along bottom trawl furrows .................................................... -

New Zealand Fishes a Field Guide to Common Species Caught by Bottom, Midwater, and Surface Fishing Cover Photos: Top – Kingfish (Seriola Lalandi), Malcolm Francis

New Zealand fishes A field guide to common species caught by bottom, midwater, and surface fishing Cover photos: Top – Kingfish (Seriola lalandi), Malcolm Francis. Top left – Snapper (Chrysophrys auratus), Malcolm Francis. Centre – Catch of hoki (Macruronus novaezelandiae), Neil Bagley (NIWA). Bottom left – Jack mackerel (Trachurus sp.), Malcolm Francis. Bottom – Orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus), NIWA. New Zealand fishes A field guide to common species caught by bottom, midwater, and surface fishing New Zealand Aquatic Environment and Biodiversity Report No: 208 Prepared for Fisheries New Zealand by P. J. McMillan M. P. Francis G. D. James L. J. Paul P. Marriott E. J. Mackay B. A. Wood D. W. Stevens L. H. Griggs S. J. Baird C. D. Roberts‡ A. L. Stewart‡ C. D. Struthers‡ J. E. Robbins NIWA, Private Bag 14901, Wellington 6241 ‡ Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, PO Box 467, Wellington, 6011Wellington ISSN 1176-9440 (print) ISSN 1179-6480 (online) ISBN 978-1-98-859425-5 (print) ISBN 978-1-98-859426-2 (online) 2019 Disclaimer While every effort was made to ensure the information in this publication is accurate, Fisheries New Zealand does not accept any responsibility or liability for error of fact, omission, interpretation or opinion that may be present, nor for the consequences of any decisions based on this information. Requests for further copies should be directed to: Publications Logistics Officer Ministry for Primary Industries PO Box 2526 WELLINGTON 6140 Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0800 00 83 33 Facsimile: 04-894 0300 This publication is also available on the Ministry for Primary Industries website at http://www.mpi.govt.nz/news-and-resources/publications/ A higher resolution (larger) PDF of this guide is also available by application to: [email protected] Citation: McMillan, P.J.; Francis, M.P.; James, G.D.; Paul, L.J.; Marriott, P.; Mackay, E.; Wood, B.A.; Stevens, D.W.; Griggs, L.H.; Baird, S.J.; Roberts, C.D.; Stewart, A.L.; Struthers, C.D.; Robbins, J.E. -

Horoirangi Marine Reserve

Horoirangi Marine Reserve Introduction Horoirangi Marine Reserve comes into being on 26 January 2006 after which all marine life within its boundaries will be totally protected; no fishing will be allowed. This fact sheet provides some brief information on the new marine reserve which was applied for by Forest and Bird. A more detailed pamphlet will be available in the next few months. The reserve’s name was chosen by Nelson iwi. Horoirangi was an important Maori ancestor who is regarded as a guardian of her people bringing Sea Anemones fertility and abundance. Horoirangi is also the Photo: Ken Grange Maori name of the highest peak overlooking the marine reserve. How to get there Measuring 904 ha and a little over 5 km in length, The subtidal reefs extend from around 100 m to Horoirangi Marine Reserve is around 11 km north over 400 m offshore and down to a depth of about of Nelson city along the eastern side of Tasman 20 m. Soft sediment habitats occur beyond the Bay. It extends north-east from Glenduan (“the outer reef edge with various mixes of mud, sand, Glen”) to Ataata Point, the southern headland of shell and gravel closer to shore and soft mud Cable Bay, and offshore for one nautical mile (see offshore. map). Although fishing will not be allowed in the marine The reserve is accessible by foot from the Glen. reserve, other forms of recreation are welcomed. Boulder Bank Sponge Kayaks can also be launched and retrieved - with Walking, exploring the intertidal zone, kayaking, Photo: Ken Grange care - across the boulder bank. -

Intrinsic Vulnerability in the Global Fish Catch

The following appendix accompanies the article Intrinsic vulnerability in the global fish catch William W. L. Cheung1,*, Reg Watson1, Telmo Morato1,2, Tony J. Pitcher1, Daniel Pauly1 1Fisheries Centre, The University of British Columbia, Aquatic Ecosystems Research Laboratory (AERL), 2202 Main Mall, Vancouver, British Columbia V6T 1Z4, Canada 2Departamento de Oceanografia e Pescas, Universidade dos Açores, 9901-862 Horta, Portugal *Email: [email protected] Marine Ecology Progress Series 333:1–12 (2007) Appendix 1. Intrinsic vulnerability index of fish taxa represented in the global catch, based on the Sea Around Us database (www.seaaroundus.org) Taxonomic Intrinsic level Taxon Common name vulnerability Family Pristidae Sawfishes 88 Squatinidae Angel sharks 80 Anarhichadidae Wolffishes 78 Carcharhinidae Requiem sharks 77 Sphyrnidae Hammerhead, bonnethead, scoophead shark 77 Macrouridae Grenadiers or rattails 75 Rajidae Skates 72 Alepocephalidae Slickheads 71 Lophiidae Goosefishes 70 Torpedinidae Electric rays 68 Belonidae Needlefishes 67 Emmelichthyidae Rovers 66 Nototheniidae Cod icefishes 65 Ophidiidae Cusk-eels 65 Trachichthyidae Slimeheads 64 Channichthyidae Crocodile icefishes 63 Myliobatidae Eagle and manta rays 63 Squalidae Dogfish sharks 62 Congridae Conger and garden eels 60 Serranidae Sea basses: groupers and fairy basslets 60 Exocoetidae Flyingfishes 59 Malacanthidae Tilefishes 58 Scorpaenidae Scorpionfishes or rockfishes 58 Polynemidae Threadfins 56 Triakidae Houndsharks 56 Istiophoridae Billfishes 55 Petromyzontidae -

ASFIS ISSCAAP Fish List February 2007 Sorted on Scientific Name

ASFIS ISSCAAP Fish List Sorted on Scientific Name February 2007 Scientific name English Name French name Spanish Name Code Abalistes stellaris (Bloch & Schneider 1801) Starry triggerfish AJS Abbottina rivularis (Basilewsky 1855) Chinese false gudgeon ABB Ablabys binotatus (Peters 1855) Redskinfish ABW Ablennes hians (Valenciennes 1846) Flat needlefish Orphie plate Agujón sable BAF Aborichthys elongatus Hora 1921 ABE Abralia andamanika Goodrich 1898 BLK Abralia veranyi (Rüppell 1844) Verany's enope squid Encornet de Verany Enoploluria de Verany BLJ Abraliopsis pfefferi (Verany 1837) Pfeffer's enope squid Encornet de Pfeffer Enoploluria de Pfeffer BJF Abramis brama (Linnaeus 1758) Freshwater bream Brème d'eau douce Brema común FBM Abramis spp Freshwater breams nei Brèmes d'eau douce nca Bremas nep FBR Abramites eques (Steindachner 1878) ABQ Abudefduf luridus (Cuvier 1830) Canary damsel AUU Abudefduf saxatilis (Linnaeus 1758) Sergeant-major ABU Abyssobrotula galatheae Nielsen 1977 OAG Abyssocottus elochini Taliev 1955 AEZ Abythites lepidogenys (Smith & Radcliffe 1913) AHD Acanella spp Branched bamboo coral KQL Acanthacaris caeca (A. Milne Edwards 1881) Atlantic deep-sea lobster Langoustine arganelle Cigala de fondo NTK Acanthacaris tenuimana Bate 1888 Prickly deep-sea lobster Langoustine spinuleuse Cigala raspa NHI Acanthalburnus microlepis (De Filippi 1861) Blackbrow bleak AHL Acanthaphritis barbata (Okamura & Kishida 1963) NHT Acantharchus pomotis (Baird 1855) Mud sunfish AKP Acanthaxius caespitosa (Squires 1979) Deepwater mud lobster Langouste -

Worse Things Happen at Sea: the Welfare of Wild-Caught Fish

[ “One of the sayings of the Holy Prophet Muhammad(s) tells us: ‘If you must kill, kill without torture’” (Animals in Islam, 2010) Worse things happen at sea: the welfare of wild-caught fish Alison Mood fishcount.org.uk 2010 Acknowledgments Many thanks to Phil Brooke and Heather Pickett for reviewing this document. Phil also helped to devise the strategy presented in this report and wrote the final chapter. Cover photo credit: OAR/National Undersea Research Program (NURP). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/Dept of Commerce. 1 Contents Executive summary 4 Section 1: Introduction to fish welfare in commercial fishing 10 10 1 Introduction 2 Scope of this report 12 3 Fish are sentient beings 14 4 Summary of key welfare issues in commercial fishing 24 Section 2: Major fishing methods and their impact on animal welfare 25 25 5 Introduction to animal welfare aspects of fish capture 6 Trawling 26 7 Purse seining 32 8 Gill nets, tangle nets and trammel nets 40 9 Rod & line and hand line fishing 44 10 Trolling 47 11 Pole & line fishing 49 12 Long line fishing 52 13 Trapping 55 14 Harpooning 57 15 Use of live bait fish in fish capture 58 16 Summary of improving welfare during capture & landing 60 Section 3: Welfare of fish after capture 66 66 17 Processing of fish alive on landing 18 Introducing humane slaughter for wild-catch fish 68 Section 4: Reducing welfare impact by reducing numbers 70 70 19 How many fish are caught each year? 20 Reducing suffering by reducing numbers caught 73 Section 5: Towards more humane fishing 81 81 21 Better welfare improves fish quality 22 Key roles for improving welfare of wild-caught fish 84 23 Strategies for improving welfare of wild-caught fish 105 Glossary 108 Worse things happen at sea: the welfare of wild-caught fish 2 References 114 Appendix A 125 fishcount.org.uk 3 Executive summary Executive Summary 1 Introduction Perhaps the most inhumane practice of all is the use of small bait fish that are impaled alive on There is increasing scientific acceptance that fish hooks, as bait for fish such as tuna. -

A Cyprinid Fish

DFO - Library / MPO - Bibliotheque 01005886 c.i FISHERIES RESEARCH BOARD OF CANADA Biological Station, Nanaimo, B.C. Circular No. 65 RUSSIAN-ENGLISH GLOSSARY OF NAMES OF AQUATIC ORGANISMS AND OTHER BIOLOGICAL AND RELATED TERMS Compiled by W. E. Ricker Fisheries Research Board of Canada Nanaimo, B.C. August, 1962 FISHERIES RESEARCH BOARD OF CANADA Biological Station, Nanaimo, B0C. Circular No. 65 9^ RUSSIAN-ENGLISH GLOSSARY OF NAMES OF AQUATIC ORGANISMS AND OTHER BIOLOGICAL AND RELATED TERMS ^5, Compiled by W. E. Ricker Fisheries Research Board of Canada Nanaimo, B.C. August, 1962 FOREWORD This short Russian-English glossary is meant to be of assistance in translating scientific articles in the fields of aquatic biology and the study of fishes and fisheries. j^ Definitions have been obtained from a variety of sources. For the names of fishes, the text volume of "Commercial Fishes of the USSR" provided English equivalents of many Russian names. Others were found in Berg's "Freshwater Fishes", and in works by Nikolsky (1954), Galkin (1958), Borisov and Ovsiannikov (1958), Martinsen (1959), and others. The kinds of fishes most emphasized are the larger species, especially those which are of importance as food fishes in the USSR, hence likely to be encountered in routine translating. However, names of a number of important commercial species in other parts of the world have been taken from Martinsen's list. For species for which no recognized English name was discovered, I have usually given either a transliteration or a translation of the Russian name; these are put in quotation marks to distinguish them from recognized English names. -

Blue Cod Mild-Tasting White Fish Extremely Cost Effective Very Healthy Alternative Blue Cod Blue Cod Is Wild Caught in New Zealand

® QUALITY SINCE 1899 Blue Cod Mild-Tasting White Fish Extremely Cost Effective Very Healthy Alternative Blue Cod Blue cod is wild caught in New Zealand. It is a white fin-fish, and produces good fillets that are low in fat, which allows for a mild taste and numerous applications. Toppits Blue Cod Fillets are very versatile and can be baked, broiled, fried, grilled, battered, steamed/boiled, or sautéed. Our Blue Cod is the perfect way to introduce your customers to fish. Features & Benefits • Cost effective and a great substitute for higher priced Nutrition Facts white fish such as Atlantic Cod, Pacific Cod and Valeur nutritive Per 100 g / par 100 g Patagonian Silver Hake. Amount % Daily Value Teneur % valeur quotidienne • Mild flavour creates a versatile white fish and makes it Calories / Calories 80 Fat / Lipides 1 g 2 % great for new fish consumers. Saturated / saturés 0 g 0 % + Trans / trans 0 g • Healthy option as it’s low in fat, saturated fatty acids and Cholesterol / Cholestérol 70 mg sodium. Sodium / Sodium 110 mg 5 % Carbohydrate / Glucides 0 g 0 % • From an MSC certified sustainable fishery www.msc.org Fibre / Fibres 0 g 0 % Sugars / Sucres 0 g • Ocean Wise Sustainable Protein / Protéines 19 g Vitamin A / Vitamine A 0 % Vitamin C / Vitamine C 0 % Calcium / Calcium 0 % Iron / Fer 0 % Item Description Brand Origin Pack SCC Blue Cod Fillets IQF, 3 oz 7147889 Toppits China 1/10 lb 10068689110189 (Skinless/Boneless) MSC OW Blue Cod Fillets IQF, 4 oz 8507871 Toppits China 1/10 lb 10068689120942 (Skinless/Boneless) MSC OW Blue Cod -

Fish, Crustaceans, Molluscs, Etc Capture Production by Species

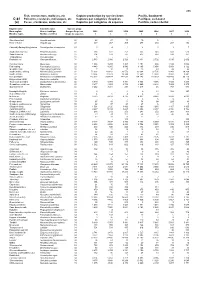

495 Fish, crustaceans, molluscs, etc Capture production by species items Pacific, Southwest C-81 Poissons, crustacés, mollusques, etc Captures par catégories d'espèces Pacifique, sud-ouest (a) Peces, crustáceos, moluscos, etc Capturas por categorías de especies Pacífico, sudoccidental English name Scientific name Species group Nom anglais Nom scientifique Groupe d'espèces 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 Nombre inglés Nombre científico Grupo de especies t t t t t t t Short-finned eel Anguilla australis 22 28 27 13 10 5 ... ... River eels nei Anguilla spp 22 337 267 209 277 210 207 152 Chinook(=Spring=King)salmon Oncorhynchus tshawytscha 23 0 4 1 2 1 1 7 Southern lemon sole Pelotretis flavilatus 31 238 322 251 335 348 608 513 Sand flounders Rhombosolea spp 31 204 193 187 437 514 530 351 Tonguefishes Cynoglossidae 31 3 - - - - - - Flatfishes nei Pleuronectiformes 31 2 580 2 986 2 729 3 431 2 702 3 015 2 602 Common mora Mora moro 32 1 308 1 234 1 403 1 154 986 1 180 1 088 Red codling Pseudophycis bachus 32 4 443 8 265 9 540 8 165 5 854 5 854 6 122 Grenadier cod Tripterophycis gilchristi 32 7 10 13 13 43 29 26 Southern blue whiting Micromesistius australis 32 72 203 43 812 26 576 30 304 32 735 23 943 29 268 Southern hake Merluccius australis 32 13 834 22 623 19 344 12 560 12 858 13 892 8 881 Blue grenadier Macruronus novaezelandiae 32 215 302 209 414 147 032 134 145 119 329 103 489 96 119 Ridge scaled rattail Macrourus carinatus 32 - - - - - 9 14 Thorntooth grenadier Lepidorhynchus denticulatus 32 5 349 5 304 6 341 3 855 4 056 3 725 3 264 Grenadiers, rattails nei Macrouridae 32 3 877 4 253 3 732 2 660 2 848 7 939 8 970 Gadiformes nei Gadiformes 32 3 252 3 281 298 1 217 46 767 886 Broadgilled hagfish Eptatretus cirrhatus 33 2 - 0 0 11 508 347 Sea catfishes nei Ariidae 33 4 6 4 4 4 .. -

Inshore Trawl Survey of the Canterbury Bight and Pegasus Bay, December 1998-January 1999

TWs Taihoro Nukurangi Inshore trawl survey of the Canterbury Bight and Pegasus Bay, December 1998-January 1999 M. L. Stevenson and M. P. Beentjes Final Research Report for Ministry of Fisheries Research Project INT9802 National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research June 1999 Final Research Report Author: M. Stevenson and M. Beentjes Title: Inshore trawl survey of the Canterbury Bight and Pegasus Bay, December 1998-January 1999 Date: 22 June 1999 Contractor: National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research Limited Project Title: Estimation of inshore fish abundance along the east coast of the South Island from Kaikoura to Shag Point using trawl surveys. Project Code: 1NT9802 Project Leader: Michael Beentjes Duration of Project: Start Date: 1 October 1998 Completion date: 30 June 1999 Executive Summary: The trawl survey was successfully completed in December 1998-Januray 1999 and the data have been checked and loaded onto the trawl database. Preliminary results were presented to Inshore Working Groups 1 & 2 in February 1999. A NIWA Technical Report has been prepared (see the attached). Biomass estimates for the most abundant species and other commercially important species for which more than 200 kg were caught have been determined. Catch rates, distribution, and scaled length frequencies for the major commercial species have been charted. Length-weight relationships for the target species, rough skate, smooth skate, dark ghost shark, lemon sole, new Zealand dole, sand flounder, and hapuku have been calculated from the data. Target coefficients of variation were achieved on all four target species, elephantfish, red gurnard, giant stargazer, and juvenile red cod < 41 cm total length. -

Relative Abundance, Size and Age Structure, and Stock Status of Blue Cod Off North Otago in 2018

Relative abundance, size and age structure, and stock status of blue cod off north Otago in 2018 New Zealand Fisheries Assessment Report 2019/07 M.P. Beentjes M. Fenwick ISSN 1179-5352 (online) ISBN 978-1-98-857182-9 (online) February 2019 Requests for further copies should be directed to: Publications Logistics Officer Ministry for Primary Industries PO Box 2526 WELLINGTON 6140 Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0800 00 83 33 Facsimile: 04-894 0300 This publication is also available on the Ministry for Primary Industries websites at: http://www.mpi.govt.nz/news-and-resources/publications http://fs.fish.govt.nz go to Document library/Research reports © Crown Copyright – Fisheries New Zealand Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Status of the north Otago blue cod stocks ............................................................................... 3 1.2 North Otago bathymetry and substrate .................................................................................... 3 1.3 Blue cod potting surveys ......................................................................................................... 3 1.4 Previous north Otago blue cod potting surveys ....................................................................... 4 1.5 Objectives ................................................................................................................................ 4 2. METHODS .....................................................................................................................................