Affirmative Action Reconceived: a Comparative Study of Constitutional Precommitments to Group Preferences for Racial Minorities and Women

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stephen Philip Cohen the Idea Of

00 1502-1 frontmatter 8/25/04 3:17 PM Page iii the idea of pakistan stephen philip cohen brookings institution press washington, d.c. 00 1502-1 frontmatter 8/25/04 3:17 PM Page v CONTENTS Preface vii Introduction 1 one The Idea of Pakistan 15 two The State of Pakistan 39 three The Army’s Pakistan 97 four Political Pakistan 131 five Islamic Pakistan 161 six Regionalism and Separatism 201 seven Demographic, Educational, and Economic Prospects 231 eight Pakistan’s Futures 267 nine American Options 301 Notes 329 Index 369 00 1502-1 frontmatter 8/25/04 3:17 PM Page vi vi Contents MAPS Pakistan in 2004 xii The Subcontinent on the Eve of Islam, and Early Arab Inroads, 700–975 14 The Ghurid and Mamluk Dynasties, 1170–1290 and the Delhi Sultanate under the Khaljis and Tughluqs, 1290–1390 17 The Mughal Empire, 1556–1707 19 Choudhary Ramat Ali’s 1940 Plan for Pakistan 27 Pakistan in 1947 40 Pakistan in 1972 76 Languages of Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Northwest India 209 Pakistan in Its Larger Regional Setting 300 01 1502-1 intro 8/25/04 3:18 PM Page 1 Introduction In recent years Pakistan has become a strategically impor- tant state, both criticized as a rogue power and praised as being on the front line in the ill-named war on terrorism. The final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States iden- tifies Pakistan, along with Afghanistan and Saudi Arabia, as a high- priority state. This is not a new development. -

Indigenous and Tribal People's Rights Over Their Ancestral Lands

INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc. 56/09 30 December 2009 Original: Spanish INDIGENOUS AND TRIBAL PEOPLES’ RIGHTS OVER THEIR ANCESTRAL LANDS AND NATURAL RESOURCES Norms and Jurisprudence of the Inter‐American Human Rights System 2010 Internet: http://www.cidh.org E‐mail: [email protected] OAS Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data Derechos de los pueblos indígenas y tribales sobre sus tierras ancestrales y recursos naturales: Normas y jurisprudencia del sistema interamericano de derechos humanos = Indigenous and tribal people’s rights over their ancestral lands and natural resources: Norms and jurisprudence of the Inter‐American human rights system / [Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights.] p. ; cm. (OEA documentos oficiales ; OEA/Ser.L)(OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L) ISBN 978‐0‐8270‐5580‐3 1. Human rights‐‐America. 2. Indigenous peoples‐‐Civil rights‐‐America. 3. Indigenous peoples‐‐Land tenure‐‐America. 4. Indigenous peoples‐‐Legal status, laws, etc.‐‐America. 5. Natural resources‐‐Law and legislation‐‐America. I. Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights. II Series. III. Series. OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L. OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc.56/09 Document published thanks to the financial support of Denmark and Spain Positions herein expressed are those of the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights and do not reflect the views of Denmark or Spain Approved by the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights on December 30, 2009 INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS MEMBERS Luz Patricia Mejía Guerrero Víctor E. Abramovich Felipe González Sir Clare Kamau Roberts Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro Florentín Meléndez Paolo G. Carozza ****** Executive Secretary: Santiago A. -

Queer Theory, Ethno/Musicology, and the Disorientation of the Field

Queer Theory, Ethno/Musicology, and the Disorientation of the Field Steven Moon We spend significant time and space in our academic lives positioning ourselves: within the theory of the field, in regard to the institution, within networks of interlocutors, scholars, performers, and so on. We are likewise trained to critique those positions, to identify modes of power in their myriad manifestations, and to work towards more equitable methods and theory. That is, we constantly are subject to attempts of disciplinary orienta- tion, and constantly negotiate forms of re-orientation. Sara Ahmed reminds us that we might ask not only how we are oriented within our discipline, but also about 1) how the discipline itself is oriented, and 2) how orien- tation within sexuality shapes how our bodies extend into space (2006). This space—from disciplinary space, to performance space, to the space of fieldwork and the archive—is a boundless environment cut by the trails of the constant reorientation of those before us. But our options are more than the dichotomy between “be oriented” and “re-orient oneself.” In this essay, I examine the development of the ethno/musicologies’ (queer) theoretical borrowings from anthropology, sociology, and literary/cultural studies in order to historicize the contemporary queer moment both fields are expe- riencing and demonstrate the ways in which it might dis-orient the field. I trace the histories of this queer-ing trend by beginning with early concep- tualizations of the ethno/musicological projects, scientism, and quantita- tive methods. This is in relation to the anthropological method of ethno- cartography in order to understand the historical difficulties in creating a queer qualitative field, as opposed to those based in hermeneutics. -

Unit 16 Ethnicity Politics and State

UNIT 16 ETHNICITY POLITICS AND STATE Structure 16.1 Introduction 16.2 Ethnicity : Meaning 16.2.1 Characteristics of Ethnic Groups 16.2.2 Ethnicity 16.3 Ethnicity and State 16.4 Assimilation and Integration 16.5 Pluralism 16.5.1 Multiculturalism 16.6 Power Sharing 16.6.1 Federalism 16.6.2 Consociationalism 16.7 Summary 16.8 Exercises 16.1 INTRODUCTION Almost all states today are marked by diversity and difference-differences of ethnicity, culture and religion in addition to many individual differences which characterise members of societies. A large number of these states are confronted with ethnic conflicts, assertion of ethno-religious identity, movements for recognition, rights of self determination etc. In view of the fact that the prospect for peace and war, the maintenance of national unity and the fundamental human rights in many parts of the world and in many ways depend on the adequate solution of ethnic tensions the way States deal with the question has become one of the most important political issues in the contemporary world. Of course each state has its own unique way to deal with or responding to its cultural diversities yet there are some general approaches which states adopt, or have been suggested by experts. An understanding of the responses of States and approaches in dealing with ethnic groups will be useful for the students of comparative politics to analyse the phenomena in general and specific situations as also to make policy suggestions. 16.2 ETHNICITY: MEANING Race, ethnicity and cultural identity are complex concepts that are historically, socially and contextually based. -

Conditional Consociationalism: Electoral Systems and Grand Coalitions∗

Conditional Consociationalism: Electoral Systems and Grand Coalitions∗ Nils-Christian Bormanny March 25, 2011 Abstract Consociationalism is a complex set of rules and norms that is sup- posed to enable democratic governance and peaceful coexistence of different social segments in plural societies. Statistical studies of con- flict often reduce it to either a PR or federalism dummy in a regression. I extract the core definition of consociationalism from Lijphart's writ- ing and explicitly link its institutional and behavioral dimensions. I also address the possible endogeneity of electoral systems and show that once endogeneity is accounted for PR has a positive effect on eth- nic elite cooperation although historical, socio-structural and interna- tional factors exert a more robust influence. A history of violence in a country seems to antagonize elites and hinder cooperation. ∗Paper to be presented at the ECPR Joint Sessions workshop on Political Violence and Institutions from 12-17 April in St. Gallen, Switzerland. I thank Manuel Vogt and Julian Wucherpfennig for helpful discussion and comments. yCenter of Comparative and International Studies, ETH Zurich, Switzerland. Email: [email protected] 1 1 Introduction Was Lijphart (1977, 238) correct in pronouncing that \[f]or many of the plural societies of the non-Western world (. ) the realistic choice is not between the British normative model of democracy and the consociational model, but between consociational democracy and no democracy at all?" The appraisal of the alleged blessings of consociationalism has been incom- plete and/or hotly disputed. Most studies focus on the application to single cases, and large-N studies have only gained systematic insight at the expense of conceptual clarity. -

The Demise of the Nation-State: Towards a New Theory of the State Under International Law

The Demise of the Nation-State: Towards a New Theory of the State Under International Law By James D. Wilets* I. INTRODUCTION It may seem premature to speak of the demise of the nation-state' when the last decade has seen the proliferation of ever-smaller nation-states throughout Eastern Europe and Asia and the demand for secession from national move- ments in countries as diverse as Canada, Yugoslavia, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Rus- sia, Spain and India. Nevertheless, the seemingly contradictory centrifugal forces of nationalism and the centripetal forces of confederation and federation are simply different stages of the same historical process that have been occur- ring since before the 17th century. 2 This historical process has consisted of * Assistant Professor of International Law, Nova Southeastern University, Shepard Broad Law Center; Executive Director, Inter-American Center for Human Rights. J.D., Columbia Univer- sity School of Law, 1987; M.A., Yale University, 1994. Consultant to the National Democratic Institute, 1994; the International Human Rights Law Group, 1992; and the United Nations in its Second Half Century, a project proposed by UN Secretary-General Boutros-Ghali and funded by the Ford Foundation. I would like to thank Sir Michael Howard and Michael Reisman for their valuable comments on the first drafts. I would also like to thank Johnny Burris, Tony Chase, Douglas Donoho, Kevin Brady, Carlo Corsetti, Luis Font, Marietta Galindez, Rhonda Gold, Elizabeth Iglesias, Jose Rodriguez, Stephen Schnably and the entire library staff at the NSU Law Center for their enormously valuable comments, input, assistance and support. Any and all errors in fact are entirely mine. -

The Kingdom of Afghanistan: a Historical Sketch George Passman Tate

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1911 The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch George Passman Tate Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tate, George Passman The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch, with an introductory note by Sir Henry Mortimer Durand. Bombay: "Times of India" Offices, 1911. 224 p., maps This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tate, G,P. The kfn&ean sf Af&mistan, DATE DUE I Mil 7 (7'8 DEDICATED, BY PERMISSION, HIS EXCELLENCY BARON HARDINGE OF PENSHURST. VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, .a- . (/. BY m HIS OBEDIENT, SERVANT THE AUTHOR. il.IEmtev 01 the Asiniic Society, Be?zg-nl, S?~rueyof I~din. dafhor of 'I Seisinqz : A Menzoir on the FJisio~y,Topo~rcrphj~, A7zliquiiies, (112d Peo$Ie of the Cozi?zt~y''; The F/.o?zlic7,.~ of Baluchisia'nn : Travels on ihe Border.? of Pe~szk n?zd Akhnnistnn " ; " ICalnf : A lMe??zoir on t7ze Cozl7~try and Fnrrzily of the Ahntadsai Khn7zs of Iinlnt" ; 4 ec. \ViTkI AN INrPR<dl>kJCTOl2Y NO'FE PRINTED BY BENNETT COLEMAN & Co., Xc. PUBLISHED AT THE " TIMES OF INDIA" OFFTCES, BOMBAY & C.1LCUTT-4, LONDON AGENCY : gg, SI-IOE LANE, E.C. -

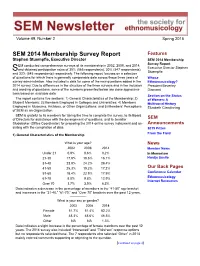

SEM 2014 Membership Survey Report Features Stephen Stuempfle, Executive Director SEM 2014 Membership

Volume 49, Number 2 Spring 2015 SEM 2014 Membership Survey Report Features Stephen Stuempfle, Executive Director SEM 2014 Membership EM conducted comprehensive surveys of its membership in 2002, 2008, and 2014, Survey Report Executive Director Stephen and obtained participation rates of 35% (565 respondents), 30% (547 respondents), S Stuempfle and 32% (545 respondents) respectively. The following report focuses on a selection of questions for which there is generally comparable data across these three years of Whose survey administration. Also included is data for some of the new questions added in the Ethnomusicology? 2014 survey. Due to differences in the structure of the three surveys and in the inclusion President Beverley and wording of questions, some of the numbers presented below are close approxima- Diamond tions based on available data. Section on the Status The report contains five sections: 1) General Characteristics of the Membership; 2) of Women: A Student Members; 3) Members Employed in Colleges and Universities; 4) Members Multivocal History Employed in Museums, Archives, or Other Organizations; and 5) Members’ Perceptions Elizabeth Clendinning of SEM as an Organization. SEM is grateful to its members for taking the time to complete the survey, to its Board of Directors for assistance with the development of questions, and to Jennifer SEM Studebaker (Office Coordinator) for preparing the 2014 online survey instrument and as- Announcements sisting with the compilation of data. 2015 Prizes From the Field 1) General Characteristics of the Membership What is your age? News 2002 2008 2014 Member News Under 21 0.9% 0.6% 0.2% In Memoriam 21-30 17.9% 19.6% 16.1% Hardja Susilo 31-40 23.9% 24.2% 29.4% 41-50 25.3% 19.2% 17.2% Our Back Pages 51-60 18.4% 22.9% 17.9% Conference Calendar 61-70 8.0% 9.8% 12.9% Ethnomusicology Internet Resources Over 70 3.7% 3.9% 6.3% Data indicates a decrease in the percentage of members in the “41-50” age bracket and increases in the “31-40,” “61-70,” and “Over 70” brackets over the past 12 years. -

Editor's Note: Indigenous Communities and COVID-19

Volume 4, Issue 1 (October 2015) Volume 9, Issue 3 (2020) http://w w w.hawaii.edu/sswork/jisd https://ucalgary.ca/journals/jisd http://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/ E-ISSN 2164-9170 handle/10125/37602 pp. 1-3 E-ISSN 2164-9170 pp. 1-15 Editor’s Note: Indigenous Communities and COVID-19: Impact and Implications R eaching Harmony Across Indigenous and Mainstream Peter Mataira ReHawaiisear cPacifich Co nUniversitytexts: A Collegen Em eofr gHealthent N andar rSocietyative CaPaulatherin eMorelli E. Burn ette TuUniversitylane U niver sofity Hawai‘i at Mānoa Michael S. Spencer ShUniversityanondora B ioflli oWashingtont Wa shington University i n St. Louis As the editors we honor those who have contributed to this special issue, Indigenous CommunitiesKey Words and COVID-19: Impact and Implications. In this time of great uncertainty and unrest Indigenous r esearch • power • decolonizing research • critical theory we felt compelled to seek a call for papers that would examine aspects of our traditional cultures focusedAbstra specificallyct on COVID-19 and its disruptions to the dimensions of our wellbeing and the Research with indigenous communities is one of the few areas of research restoration of wellness. This virus has impacted every individual and family on this planet, and, has encompassing profound controversies, complexities, ethical responsibilities, and helpedhistor iccoalesceal contex tthe of pervasiveexploitat ion intersectional and harm. O fstrugglesten this c oofm pIndigenouslexity becom ePeopless . overwhTheelmi narticlesgly appa rselectedent to th eare ea rcompellingly career resea inrch theirer wh oability endeav toors castto m lightake over the shadows of discord meaningful contributions to decolonizing research. Decolonizing research has the andca pairaci tofy t oconspiracy be a cat alyst fsurroundingor the improve dthis wel lpandemic.being and po sTheyitive so acknowledgecial change amon thatg the grief and anguish buried beneathindigen otheus csoilomm ofun intergenerationalities and beyond. -

Filipino Americans and Polyculturalism in Seattle, Wa

FILIPINO AMERICANS AND POLYCULTURALISM IN SEATTLE, WA THROUGH HIP HOP AND SPOKEN WORD By STEPHEN ALAN BISCHOFF A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN AMERICAN STUDIES WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY Department of American Studies DECEMBER 2008 To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the thesis of STEPHEN ALAN BISCHOFF find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. _____________________________________ Chair, Dr. John Streamas _____________________________________ Dr. Rory Ong _____________________________________ Dr. T.V. Reed ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Since I joined the American Studies Graduate Program, there has been a host of faculty that has really helped me to learn what it takes to be in this field. The one professor that has really guided my development has been Dr. John Streamas. By connecting me to different resources and his challenging the confines of higher education so that it can improve, he has been an inspiration to finish this work. It is also important that I mention the help that other faculty members have given me. I appreciate the assistance I received anytime that I needed it from Dr. T.V. Reed and Dr. Rory Ong. A person that has kept me on point with deadlines and requirements has been Jean Wiegand with the American Studies Department. She gave many reminders and explained answers to my questions often more than once. Debbie Brudie and Rose Smetana assisted me as well in times of need in the Comparative Ethnic Studies office. My cohort over the years in the American Studies program have developed my thinking and inspired me with their own insight and work. -

Peoples of India

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION WAR BACKGROUND STUDIES NUMBER EIGHTEEN PEOPLES OF INDIA By WILLIAM H. GILBERT, JR. (Publication 3767) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION APRIL 29, 1944 BALTIMORE, MD., U. 8. A. CONTENTS Page Introduction 1 Geography 2 Topographic features 3 Geology 6 Climate 7 Vegetation 7 Animals 10 Natural regions 12 Cultures and races 13 Archeology 13 Material culture 15 Racial types 17 Temperamental characteristics 19 Population, health, and nutrition 20 Marriage and the family 24 Economic aspects 25 History 28 Government 34 Political areas of today 36 Languages 40 Religions and sects 46 Fine arts 53 Games and recreations 54 Primitive areas 55 Caste areas 56 Cultural and ethnic divisions 57 Summary outline of the social units of India 59 Castes and tribes 60 The system 60 Brahmans 64 Rajputs 65 Banias and allied business castes 67 Sudra or low castes 68 Muslim groups 69 Outlying systems of caste 71 Hill tribes 75 Conclusion 82 Selected bibliography 84 TABLES Page 1. Increase in the population of India 22 2. Approximate dates of major racial events in Indian history 34 3. Steps in the constitutional history of British India 35 4. Political parties and groupings in India 37 5. Classification of caste groups, with examples 81 iii . IV ILLUSTRATIONS ILLUSTRATIONS PLATES Page 1. Nanga Valley, Himalayan border of Afghanistan 1 2. Upper, Himalayas near Darjeeling 4 Lower, Vale of Kashmir 4 3. Upper, Rice planting in wet rice area 4 Lower, Coconut groves on the Malabar Coast 4 4. Upper, Plucking tea 4 Lower, Bathing ghat 4 5. -

Asia and Oceania Jack Dentith, Emily Hong, Irwin Loy, Farah Mihlar, Daniel Openshaw, Jacqui Zalcberg Right: Uighurs in Kazakhstan Picking Fruit from Central a Tree

ARCTIC OCEAN RUSSIA JAPAN KAZAKHSTAN NORTH MONGOLIA KOREA UZBEKISTAN SOUTH TURKMENISTAN KOREA KYRGYZSTAN TAJIKISTAN PACIFIC Jammu and AFGHANIS- Kashmir CHINA TAN OCEAN PAKISTAN TIBET Taiwan NEPAL BHUTAN BANGLADESH Hong Kong INDIA BURMA LAOS PHILIPPINES THAILAND VIETNAM CAMBODIA Andaman and Nicobar BRUNEI SRI LANKA Islands Bougainville PAPUA NEW MALAYSIA SOLOMON ISLANDS MALDIVES GUINEA SINGAPORE Borneo Sulawesi Wallis and Futuna (FR.) Sumatra INDONESIA TIMOR-LESTE FIJI ISLANDS French Polynesia (FR.) Java New Caledonia (FR.) INDIAN OCEAN AUSTRALIA NEW ZEALAND Asia and Oceania Jack Dentith, Emily Hong, Irwin Loy, Farah Mihlar, Daniel Openshaw, Jacqui Zalcberg Right: Uighurs in Kazakhstan picking fruit from Central a tree. Carolyn Drake/Panos. which affects the health of the most vulnerable people living in the region. In March, the Asian Asia Development Bank (ADB) reported that the shrinking of the Aral Sea and drying up of two Daniel Openshaw major rivers, the Amu Darya and Syr Darya, would particularly affect Karakalpakstan – an inority groups live in some of the autonomous region of Uzbekistan, home to the poorest regions of Central Asia; majority of the country’s Karakalpak population, M Pamiris in Gorno-Badakhshan as highlighted in MRG’s 2012 State of the World’s Autonomous Province in Tajikistan; Uzbeks Minorities and Indigenous Peoples. in South Kazakhstan province; Karakalpaks in In an already poor region, climate change Uzbekistan’s Karakalpakstan region; and high is especially significantly affecting the most numbers of Uzbeks and Tajiks in Kyrgyzstan’s vulnerable. Most people in Karakalpakstan Ferghana Valley. Poverty has a direct impact depend on agriculture, so water shortages have on their health.