Program Notes for Graduate Recital Season E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eastman School of Music, Thrill Every Time I Enter Lowry Hall (For- Enterprise of Studying, Creating, and Loving 26 Gibbs Street, Merly the Main Hall)

EASTMAN NOTESFALL 2015 @ EASTMAN Eastman Weekend is now a part of the University of Rochester’s annual, campus-wide Meliora Weekend celebration! Many of the signature Eastman Weekend programs will continue to be a part of this new tradition, including a Friday evening headlining performance in Kodak Hall and our gala dinner preceding the Philharmonia performance on Saturday night. Be sure to join us on Gibbs Street for concerts and lectures, as well as tours of new performance venues, the Sibley Music Library and the impressive Craighead-Saunders organ. We hope you will take advantage of the rest of the extensive Meliora Weekend programming too. This year’s Meliora Weekend @ Eastman festivities will include: BRASS CAVALCADE Eastman’s brass ensembles honor composer Eric Ewazen (BM ’76) PRESIDENTIAL SYMPOSIUM: THE CRISIS IN K-12 EDUCATION Discussion with President Joel Seligman and a panel of educational experts AN EVENING WITH KEYNOTE ADDRESS EASTMAN PHILHARMONIA KRISTIN CHENOWETH BY WALTER ISAACSON AND EASTMAN SCHOOL The Emmy and Tony President and CEO of SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Award-winning singer the Aspen Institute and Music of Smetana, Nicolas Bacri, and actress in concert author of Steve Jobs and Brahms The Class of 1965 celebrates its 50th Reunion. A highlight will be the opening celebration on Friday, featuring a showcase of student performances in Lowry Hall modeled after Eastman’s longstanding tradition of the annual Holiday Sing. A special medallion ceremony will honor the 50th class to commemorate this milestone. The sisters of Sigma Alpha Iota celebrate 90 years at Eastman with a song and ritual get-together, musicale and special recognition at the Gala Dinner. -

Recommended Solos and Ensembles Tenor Trombone Solos Sång Till

Recommended Solos and Ensembles Tenor Trombone Solos Sång till Lotta, Jan Sandström. Edition Tarrodi: Stockholm, Sweden, 1991. Trombone and piano. Requires modest range (F – g flat1), well-developed lyricism, and musicianship. There are two versions of this piece, this and another that is scored a minor third higher. Written dynamics are minimal. Although phrases and slurs are not indicated, it is a SONG…encourage legato tonguing! Stephan Schulz, bass trombonist of the Berlin Philharmonic, gives a great performance of this work on YouTube - http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mn8569oTBg8. A Winter’s Night, Kevin McKee, 2011. Available from the composer, www.kevinmckeemusic.com. Trombone and piano. Explores the relative minor of three keys, easy rhythms, keys, range (A – g1, ossia to b flat1). There is a fine recording of this work on his web site. Trombone Sonata, Gordon Jacob. Emerson Edition: Yorkshire, England, 1979. Trombone and piano. There are no real difficult rhythms or technical considerations in this work, which lasts about 7 minutes. There is tenor clef used throughout the second movement, and it switches between bass and tenor in the last movement. Range is F – b flat1. Recorded by Dr. Ron Babcock on his CD Trombone Treasures, and available at Hickey’s Music, www.hickeys.com. Divertimento, Edward Gregson. Chappell Music: London, 1968. Trombone and piano. Three movements, range is modest (G-g#1, ossia a1), bass clef throughout. Some mixed meter. Requires a mute, glissandi, and ad. lib. flutter tonguing. Recorded by Brett Baker on his CD The World of Trombone, volume 1, and can be purchased at http://www.brettbaker.co.uk/downloads/product=download-world-of-the- trombone-volume-1-brett-baker. -

1 Making the Clarinet Sing

Making the Clarinet Sing: Enhancing Clarinet Tone, Breathing, and Phrase Nuance through Voice Pedagogy D.M.A Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alyssa Rose Powell, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2020 D.M.A. Document Committee Dr. Caroline A. Hartig, Advisor Dr. Scott McCoy Dr. Eugenia Costa-Giomi Professor Katherine Borst Jones 1 Copyrighted by Alyssa Rose Powell 2020 2 Abstract The clarinet has been favorably compared to the human singing voice since its invention and continues to be sought after for its expressive, singing qualities. How is the clarinet like the human singing voice? What facets of singing do clarinetists strive to imitate? Can voice pedagogy inform clarinet playing to improve technique and artistry? This study begins with a brief historical investigation into the origins of modern voice technique, bel canto, and highlights the way it influenced the development of the clarinet. Bel canto set the standards for tone, expression, and pedagogy in classical western singing which was reflected in the clarinet tradition a hundred years later. Present day clarinetists still use bel canto principles, implying the potential relevance of other facets of modern voice pedagogy. Singing techniques for breathing, tone conceptualization, registration, and timbral nuance are explored along with their possible relevance to clarinet performance. The singer ‘in action’ is presented through an analysis of the phrasing used by Maria Callas in a portion of ‘Donde lieta’ from Puccini’s La Bohème. This demonstrates the influence of text on interpretation for singers. -

Gustavo Dudamel 2020/21 Season (Long Biography)

GUSTAVO DUDAMEL 2020/21 SEASON (LONG BIOGRAPHY) Gustavo Dudamel is driven by the belief that music has the power to transform lives, to inspire, and to change the world. Through his dynamic presence on the podium and his tireless advocacy for arts education, Dudamel has introduced classical music to new audiences around the world and has helped to provide access to the arts for countless people in underserved communities. As the Music & Artistic Director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, now in his twelfth season, Dudamel’s bold programming and expansive vision led The New York Times to herald the LA Phil as “the most important orchestra in America – period.” With the COVID-19 global pandemic shutting down the majority of live performances, Dudamel has committed even more time and energy to his mission of bringing music to young people across the globe, firm in his belief that the arts play an essential role in creating a more just, peaceful, and integrated society. While quarantining in Los Angeles, he hosted a new radio program from his living room entitled “At Home with Gustavo,” sharing personal stories and musical selections as a way to bring people together during a time of isolation. The program was broadcast locally as well as internationally in both English and Spanish, with guest co-hosts including, among others, composer John Williams, his wife, actress María Valverde. Dudamel also participated in Global Citizen’s Global Goal: Unite For Our Future TV fundraising special, giving a socially-distanced performance from the Hollywood Bowl with the LA Phil and YOLA (Youth Orchestra Los Angeles). -

Mcallister Interview Transcription

Interview with Timothy McAllister: Gershwin, Adams, and the Orchestral Saxophone with Lisa Keeney Extended Interview In September 2016, the University of Michigan’s University Symphony Orchestra (USO) performed a concert program with the works of two major American composers: John Adams and George Gershwin. The USO premiered both the new edition of Concerto in F and the Unabridged Edition of An American in Paris created by the UM Gershwin Initiative. This program also featured Adams’ The Chairman Dances and his Saxophone Concerto with soloist Timothy McAllister, for whom the concerto was written. This interview took place in August 2016 as a promotion for the concert and was published on the Gershwin Initiative’s YouTube channel with the help of Novus New Music, Inc. The following is a full transcription of the extended interview, now available on the Gershwin channel on YouTube. Dr. Timothy McAllister is the professor of saxophone at the University of Michigan. In addition to being the featured soloist of John Adams’ Saxophone Concerto, he has been a frequent guest with ensembles such as the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Lisa Keeney is a saxophonist and researcher; an alumna of the University of Michigan, she works as an editing assistant for the UM Gershwin Initiative and also independently researches Gershwin’s relationship with the saxophone. ORCHESTRAL SAXOPHONE LK: Let’s begin with a general question: what is the orchestral saxophone, and why is it considered an anomaly or specialty instrument in orchestral music? TM: It’s such a complicated past that we have with the saxophone. -

Transfer Learning for Piano Sustain-Pedal Detection

Transfer Learning for Piano Sustain-Pedal Detection Beici Liang, Gyorgy¨ Fazekas and Mark Sandler Centre for Digital Music, Queen Mary University of London London, United Kingdom Email: fbeici.liang,g.fazekas,[email protected] Abstract—Detecting piano pedalling techniques in polyphonic music remains a challenging task in music information retrieval. While other piano-related tasks, such as pitch estimation and onset detection, have seen improvement through applying deep learning methods, little work has been done to develop deep learning models to detect playing techniques. In this paper, we propose a transfer learning approach for the detection of sustain- pedal techniques, which are commonly used by pianists to enrich the sound. In the source task, a convolutional neural network (CNN) is trained for learning spectral and temporal contexts when the sustain pedal is pressed using a large dataset generated by a physical modelling virtual instrument. The CNN is designed Melspectrogram and experimented through exploiting the knowledge of piano acoustics and physics. This can achieve an accuracy score of MIDI & sensor 0 127 0.98 in the validation results. In the target task, the knowledge learned from the synthesised data can be transferred to detect the Fig. 1. Different representations of the same note played without (first note) or sustain pedal in acoustic piano recordings. A concatenated feature with (second note) the sustain pedal, including music score, melspectrogram vector using the activations of the trained convolutional layers is and messages from MIDI or sensor data. extracted from the recordings and classified into frame-wise pedal press or release. We demonstrate the effectiveness of our method in acoustic piano recordings of Chopin’s music. -

The Clarinet and Piano

REVIEWS The explanations are succinct without CLARINET AND PIANO BOOKS sacrificing depth of understanding. The Brian Balmages. Dream Sonatina for Kornel Wolak. Articulation Types for pictures highlighting each muscle group are well presented and clear, and the clarinet and piano. Potenza Music, Clarinet. Music Mind Inc., 2017. 54 2015. Duration 10’30” $24.95 pp. PDF e-book $14.99, hard copy bibliography of materials for additional $19.99 study compliments his explanations nicely. American composer Brian Balmages I found this part of the book particularly (b. 1975) has written numerous works helpful. It directs the student to additional for wind and brass instruments. Dream exercises and methods that will help refine Sonatina was composed for clarinetist the technique in question. Articulation Marguerite Levin and premiered by Types for Clarinet is an excellent primer her in Weill Recital Hall, New York and first step in the understanding and City. Balmages fulfilled the specifics of application of the various available the commission by composing a work reflecting life in his 30s. For Balmages articulations. It was an enjoyable read, this centered on the birth of his two and I recommend it to anyone looking to children and three types of dreams they present articulation concepts to students experienced: daydreams, sweet dreams in a fresh and novel way. and bad dreams. The dreams are each Kornel Wolak’s book Articulation Types – Osiris Molina portrayed in a separate movement. for Clarinet is an extension of his work for The music is well-written, convincing Music Mind Inc. and his graduate research and of medium-hard difficulty, and it uses at the University of Toronto. -

DEREK BERMEL: VOICES DUST DANCES | THRACIAN ECHOES | ELIXIR DEREK BERMEL B

DEREK BERMEL: VOICES DUST DANCES | THRACIAN ECHOES | ELIXIR DEREK BERMEL b. 1967 DUST DANCES [1] DUST DANCES (1994) 9:26 THRACIAN ECHOES [2] THRACIAN ECHOES (2002) 19:23 ELIXIR [3] ELIXIR (2006) 7:21 VOICES, FOR SOLO CLARINET AND ORCHESTRA VOICES, FOR SOLO CLARINET AND ORCHESTRA (1997) [4] I. Id 6:43 DEREK BERMEL clarinet [5] II. She Moved Thru the Fair 5:46 BOSTON MODERN ORCHESTRA PROJECT [6] III. Jamm on Toast 6:12 GIL ROSE, CONDUCTOR TOTAL 54:54 2 COMMENT idea in the orchestral realm by writing myself a clarinet concerto. My thoughts immediately turned to two of my favorite musicians, bass clarinetist Eric Dolphy and bassist Charles Mingus. Their conversational rapport inspired the first movement—called “Id”—and the rest of the concerto followed from there. I dedicated Voices to my father, who taught me By Derek Bermel an enormous amount about theatre. The outer movements more fully embrace my jazz From an early age, I was obsessed with the orchestra. During my preteen years I would background—using techniques including glissandi, growl tones, and flutter tongue—with return from the public library with armfuls of LP records—Stravinsky, Bartok, Debussy, a nod to the bittersweet “keening” of Irish folksong in the middle movement. Berg, Mussorgsky, Ravel, Copland, Britten, Webern, Messiaen, Ives. During the same Another tradition that had always fascinated me was Bulgarian folk music. In August period my knowledge of jazz was deepening. When my grandmother bought me a beat- 2001, I traveled to Plovdiv, Bulgaria, where I spent six months learning the Thracian folk up piano for $300 (she overpaid), I immediately began to reenact the works of Thelonious style with clarinetist Nikola Iliev. -

Grow Your Art Residency Luciana Souza Thursday, November 7, 2019 Brown Hall 7:30 P.M

Grow Your Art Residency Luciana Souza Thursday, November 7, 2019 Brown Hall 7:30 p.m. Doralice Antonio Almeida and Dorival Caymmi Dona Lu Marco Pereira He Was Too Good To Me Music by Richard Rodgers Lyrics by Lorenz Hart These Things Luciana Souza Say No To You Luciana Souza In March (I Remember) Luciana Souza Só Danço Samba Music by Antonio Carlos Jobim Lyrics by Vinicius De Moraes Ester Wiesnerova, voice Priya Carlberg, voice Ian Buss, tenor saxophone Moshe Elmakias, piano Andres Orco-Zerpa, guitar Andrew Schiller, bass Avery Logan, drums Intermission No Wonder Luciana Souza, arranged by Jim McNeely Heaven Duke Ellington, arranged by Guillermo Klein Choro Dançado Maria Schneider A Felicidade Music by Antonio Carlos Jobim Lyrics by Vinicius De Moraes arranged by Ken Schaphorst Cravo e Canela Milton Nascimento, arranged by Vince Mendoza NEC Jazz Orchestra Ken Schaphorst, conductor Aaron Dutton, soprano and alto saxophones, flute, clarinet Samantha Spear, alto saxophone, clarinet, flute, piccolo Jesse Beckett-Herbert, tenor saxophone, flute, clarinet Declan Sheehy-Moss, tenor saxophone, clarinet, bass clarinet Nick Suchecki, baritone saxophone, contra-alto clarinet, bass clarinet Trumpets Miles Keingstein Massimo Paparello Eliza Block Daniel Hirsch Trombones Michael Prentky Michael Sabin Sam Margolis Dorien Tate Piano Moshe Elmakias Guitar Andres Orco-Zerpa Bass Domenico Botelho Drums Charlie Weller Born in São Paulo, Brazil, Ms. Souza grew up in a family of Bossa Nova innovators - her father, a singer and songwriter, her mother, a poet and lyricist. Ms. Souza’s work as a performer transcends traditional boundaries around musical styles, offering solid roots in jazz, sophisticated lineage in world music, and an enlightened approach to new music. -

By Aaron Jay Kernis

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2016 “A Voice, A Messenger” by Aaron Jay Kernis: A Performer's Guide and Historical Analysis Pagean Marie DiSalvio Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation DiSalvio, Pagean Marie, "“A Voice, A Messenger” by Aaron Jay Kernis: A Performer's Guide and Historical Analysis" (2016). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3434. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3434 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. “A VOICE, A MESSENGER” BY AARON JAY KERNIS: A PERFORMER’S GUIDE AND HISTORICAL ANALYSIS A Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Pagean Marie DiSalvio B.M., Rowan University, 2011 M.M., Illinois State University, 2013 May 2016 For my husband, Nicholas DiSalvio ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee, Dr. Joseph Skillen, Prof. Kristin Sosnowsky, and Dr. Brij Mohan, for their patience and guidance in completing this document. I would especially like to thank Dr. Brian Shaw for keeping me focused in the “present time” for the past three years. Thank you to those who gave me their time and allowed me to interview them for this project: Dr. -

Miriam Gideon's Cantata, the Habitable Earth

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2003 Miriam Gideon's cantata, The aH bitable Earth: a conductor's analysis Stella Panayotova Bonilla Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Bonilla, Stella Panayotova, "Miriam Gideon's cantata, The aH bitable Earth: a conductor's analysis" (2003). LSU Major Papers. 20. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/20 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MIRIAM GIDEON’S CANTATA, THE HABITABLE EARTH: A CONDUCTOR’S ANALYSIS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Stella Panayotova Bonilla B.M., State Academy of Music, Sofia, Bulgaria, 1991 M.M., Louisiana State University, 1994 August 2003 ©Copyright 2003 Stella Panayotova Bonilla All rights reserved ii DEDICATION To you mom, and to the memory of my beloved father. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks to Dr. Kenneth Fulton for his guidance through the years, his faith in me and his invaluable help in accomplishing this project. Thanks to Dr. Robert Peck for his inspirational insight. Thanks to Dr. Cornelia Yarbrough and Dr. -

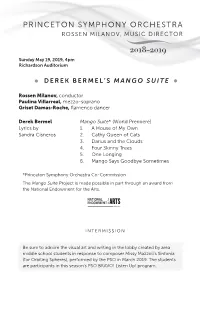

Mango Suite Program Pages

PRINCETON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ROSSEN MILANOV, MUSIC DIRECTOR 2018–2019 Sunday May 19, 2019, 4pm Richardson Auditorium DEREK BERMEL’S MANGO SUITE Rossen Milanov, conductor Paulina Villarreal, mezzo-soprano Griset Damas-Roche, flamenco dancer Derek Bermel Mango Suite* (World Premiere) Lyrics by 1. A House of My Own Sandra Cisneros 2. Cathy Queen of Cats 3. Darius and the Clouds 4. Four Skinny Trees 5. One Longing 6. Mango Says Goodbye Sometimes *Princeton Symphony Orchestra Co-Commission The Mango Suite Project is made possible in part through an award from the National Endowment for the Arts. INTERMISSION Be sure to admire the visual art and writing in the lobby created by area middle school students in response to composer Missy Mazzoli’s Sinfonia (for Orbiting Spheres), performed by the PSO in March 2019. The students are participants in this season’s PSO BRAVO! Listen Up! program. Manuel de Falla El amor brujo Introducción y escena (Introduction and Scene) En la cueva (In the Cave) Canción del amor dolido (Song of Love’s Sorrow) El Aparecido (The Apparition) Danza del terror (Dance of Terror) El círculo mágico (The Magic Circle) A medianoche (Midnight) Danza ritual del fuego (Ritual Fire Dance) Escena (Scene) Canción del fuego fatuo (Song of the Will-o’-the-Wisp) Pantomima (Pantomime) Danza del juego de amor (Dance of the Game of Love) Final (Finale) El sombrero de tres picos (The Three-Cornered Hat), Suite No. 1 Introduction—Afternoon Dance of the Miller’s Wife (Fandango) The Corregidor The Grapes La vida breve, Spanish Dance No. 1 This concert is made possible in part through the support of Yvonne Marcuse.