DEREK BERMEL: VOICES DUST DANCES | THRACIAN ECHOES | ELIXIR DEREK BERMEL B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LIU Post Chamber Music Festival 2014 33Rd Summer Season LIU POST CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL with the PIERROT CONSORT July 14 to July August 1, 2014

LIU Post Chamber Music Festival 2014 33rd Summer Season LIU POST CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL WITH THE PIERROT CONSORT July 14 to July August 1, 2014 SUSAN DEAVER & MAUREEN HYNES, FESTIVAL FOUNDERS SUSAN DEAVER, FESTIVAL DIRECTOR DALE STUCKENBRUCK, ASSISTANT DIRECTOR chamber ensembles ♦ chamber orchestras festival artists & participants concert series ♦ conducting program concerto competition ♦ master classes DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC LIU Post 720 Northern Blvd., Brookville, New York 11548-1300 www.liu.edu/post/chambermusic Phone: (516) 299-2103 • Fax: (516) 299-2884 e-mail: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS Mission Statement & History of the LIU Post Chamber Music Festival 3 Descriptions of Festival Programs 4-5 Credit Programs – Undergraduate, Graduate & High School Enrichment Artistry Program for young professionals & preformed chamber ensembles Performance Program for college & conservatory musicians Music Educator’s Program for Advancement of Chamber Music Advanced Program for students ages 15 to 18 Seminar Program for students ages 9 to 14 Conducting Program Classes Offered at the Festival 5 Musicianship Classes, Individual Master Classes, Chamber Music Performance Classes, Master Classes with Special Guest Artists and Educational Residencies Chamber Orchestras and Larger Ensembles 6-7 Concerto Competition 7 Festival Concerts 8 General Information 9 Facilities, Housing, Transportation, Food Service, Student and Faculty ID, Distribution of Orchestral and Chamber Music, Orientation and the Festival Office Tuition and Program -

Richard O'neill

Richard O’Neill 1276 Aikins Way Boulder, CO 80305 917.826.7041 [email protected] www.richard-oneill.com Education University of North Carolina School of the Arts 1997 High School Diploma University of Southern California, Thornton School of Music 2001 Bachelor of Music, magna cum laude The Juilliard School 2003 Master of Music The Juilliard School 2005 Artist Diploma Teaching University of Colorado, Boulder, College of Music 2020 - present Experience Artist in Residence, Takacs Quartet University of California Los Angeles, Herb Alpert School of Music 2007 - 2016 Lecturer of Viola University of Southern California, Thornton School of Music 2008 Viola Masterclasses Hello?! Orchestra (South Korea) 2012 - present Multicultural Youth Orchestra Founder, conductor and teacher Music Academy of the West, Santa Barbara 2014 - present Viola and Chamber Music Florida International University 2014 Viola Masterclass Brown University 2015 Viola Masterclass Hong Kong Academy of Performing Arts. 2016, 2018 Viola Masterclasses Scotia Festival 2017 Viola Masterclasses Asia Society, Hong Kong 2018 Viola and Chamber Music Masterclasses Mannes School of Music 2018 Viola Masterclass The Broad Stage, Santa Monica 2018 - 2019 Artist-in-residence, viola masterclasses, community events Affiliations Sejong Soloists 2001 - 2007 Principal Viola The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center 2003 - present CMS Two/Bowers YoungArtist from 2004-06 CREDIA International Artist Management 2004 - present Worldwide manager, based in South Korea Seattle Chamber Music Society -

The Clarinet and Piano

REVIEWS The explanations are succinct without CLARINET AND PIANO BOOKS sacrificing depth of understanding. The Brian Balmages. Dream Sonatina for Kornel Wolak. Articulation Types for pictures highlighting each muscle group are well presented and clear, and the clarinet and piano. Potenza Music, Clarinet. Music Mind Inc., 2017. 54 2015. Duration 10’30” $24.95 pp. PDF e-book $14.99, hard copy bibliography of materials for additional $19.99 study compliments his explanations nicely. American composer Brian Balmages I found this part of the book particularly (b. 1975) has written numerous works helpful. It directs the student to additional for wind and brass instruments. Dream exercises and methods that will help refine Sonatina was composed for clarinetist the technique in question. Articulation Marguerite Levin and premiered by Types for Clarinet is an excellent primer her in Weill Recital Hall, New York and first step in the understanding and City. Balmages fulfilled the specifics of application of the various available the commission by composing a work reflecting life in his 30s. For Balmages articulations. It was an enjoyable read, this centered on the birth of his two and I recommend it to anyone looking to children and three types of dreams they present articulation concepts to students experienced: daydreams, sweet dreams in a fresh and novel way. and bad dreams. The dreams are each Kornel Wolak’s book Articulation Types – Osiris Molina portrayed in a separate movement. for Clarinet is an extension of his work for The music is well-written, convincing Music Mind Inc. and his graduate research and of medium-hard difficulty, and it uses at the University of Toronto. -

Grow Your Art Residency Luciana Souza Thursday, November 7, 2019 Brown Hall 7:30 P.M

Grow Your Art Residency Luciana Souza Thursday, November 7, 2019 Brown Hall 7:30 p.m. Doralice Antonio Almeida and Dorival Caymmi Dona Lu Marco Pereira He Was Too Good To Me Music by Richard Rodgers Lyrics by Lorenz Hart These Things Luciana Souza Say No To You Luciana Souza In March (I Remember) Luciana Souza Só Danço Samba Music by Antonio Carlos Jobim Lyrics by Vinicius De Moraes Ester Wiesnerova, voice Priya Carlberg, voice Ian Buss, tenor saxophone Moshe Elmakias, piano Andres Orco-Zerpa, guitar Andrew Schiller, bass Avery Logan, drums Intermission No Wonder Luciana Souza, arranged by Jim McNeely Heaven Duke Ellington, arranged by Guillermo Klein Choro Dançado Maria Schneider A Felicidade Music by Antonio Carlos Jobim Lyrics by Vinicius De Moraes arranged by Ken Schaphorst Cravo e Canela Milton Nascimento, arranged by Vince Mendoza NEC Jazz Orchestra Ken Schaphorst, conductor Aaron Dutton, soprano and alto saxophones, flute, clarinet Samantha Spear, alto saxophone, clarinet, flute, piccolo Jesse Beckett-Herbert, tenor saxophone, flute, clarinet Declan Sheehy-Moss, tenor saxophone, clarinet, bass clarinet Nick Suchecki, baritone saxophone, contra-alto clarinet, bass clarinet Trumpets Miles Keingstein Massimo Paparello Eliza Block Daniel Hirsch Trombones Michael Prentky Michael Sabin Sam Margolis Dorien Tate Piano Moshe Elmakias Guitar Andres Orco-Zerpa Bass Domenico Botelho Drums Charlie Weller Born in São Paulo, Brazil, Ms. Souza grew up in a family of Bossa Nova innovators - her father, a singer and songwriter, her mother, a poet and lyricist. Ms. Souza’s work as a performer transcends traditional boundaries around musical styles, offering solid roots in jazz, sophisticated lineage in world music, and an enlightened approach to new music. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1963-1964

TANGLEWOOD Festival of Contemporary American Music August 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 1964 Sponsored by the Berkshire Music Center In Cooperation with the Fromm Music Foundation RCA Victor R£D SEAL festival of Contemporary American Composers DELLO JOIO: Fantasy and Variations/Ravel: Concerto in G Hollander/Boston Symphony Orchestra/Leinsdorf LM/LSC-2667 COPLAND: El Salon Mexico Grofe-. Grand Canyon Suite Boston Pops/ Fiedler LM-1928 COPLAND: Appalachian Spring The Tender Land Boston Symphony Orchestra/ Copland LM/LSC-240i HOVHANESS: BARBER: Mysterious Mountain Vanessa (Complete Opera) Stravinsky: Le Baiser de la Fee (Divertimento) Steber, Gedda, Elias, Mitropoulos, Chicago Symphony/Reiner Met. Opera Orch. and Chorus LM/LSC-2251 LM/LSC-6i38 FOSS: IMPROVISATION CHAMBER ENSEMBLE Studies in Improvisation Includes: Fantasy & Fugue Music for Clarinet, Percussion and Piano Variations on a Theme in Unison Quintet Encore I, II, III LM/LSC-2558 RCA Victor § © The most trusted name in sound BERKSHIRE MUSIC CENTER ERICH Leinsdorf, Director Aaron Copland, Chairman of the Faculty Richard Burgin, Associate Chairman of the Faculty Harry J. Kraut, Administrator FESTIVAL of CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN MUSIC presented in cooperation with THE FROMM MUSIC FOUNDATION Paul Fromm, President Alexander Schneider, Associate Director DEPARTMENT OF COMPOSITION Aaron Copland, Head Gunther Schuller, Acting Head Arthur Berger and Lukas Foss, Guest Teachers Paul Jacobs, Fromm Instructor in Contemporary Music Stanley Silverman and David Walker, Administrative Assistants The Berkshire Music Center is the center for advanced study in music sponsored by the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Erich Leinsdorf, Music Director Thomas D. Perry, Jr., Manager BALDWIN PIANO RCA VICTOR RECORDS — 1 PERSPECTIVES OF NEW MUSIC Participants in this year's Festival are invited to subscribe to the American journal devoted to im- portant issues of contemporary music. -

New on Naxos | September 2013

NEW ON The World’s Leading ClassicalNAXO Music LabelS SEPTEMBER 2013 © Grant Leighton This Month’s Other Highlights © 2013 Naxos Rights US, Inc. • Contact Us: [email protected] www.naxos.com • www.classicsonline.com • www.naxosmusiclibrary.com • blog.naxos.com NEW ON NAXOS | SEPTEMBER 2013 8.572996 Playing Time: 64:13 7 47313 29967 6 Johannes BRAHMS (1833–1897) Ein deutsches Requiem (A German Requiem), Op. 45 Anna Lucia Richter, soprano • Stephan Genz, baritone MDR Leipzig Radio Choir and Symphony Orchestra Marin Alsop Brahms’s A German Requiem, almost certainly triggered by the death of his mother in 1865, is one of his greatest and most popular works, quite unlike any previous Requiem. With texts taken from Luther’s translation of the Bible and an emphasis on comforting the living for their loss and on hope of the Resurrection, the work is deeply rooted in the tradition of Bach and Schütz, but is vastly different in character from the Latin Requiem of Catholic tradition with its evocation of the Day of Judgement and prayers for mercy on the souls of the dead. The success of Marin Alsop as Music Director of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra was recognized when, in 2009, her tenure was extended to 2015. In 2012 she took up the post of Chief Conductor of the São Paulo Symphony Orchestra, where she steers the orchestra in its artistic and creative programming, recording ventures and its education and outreach activities. Marin Alsop © Grant Leighton Companion Titles 8.557428 8.557429 8.557430 8.570233 © Christiane Höhne © Peter Rigaud MDR Leipzig Radio Choir MDR Leipzig Radio Symphony Orchestra © Jessylee Anna Lucia Richter Stephan Genz 2 NEW ON NAXOS | SEPTEMBER 2013 © Victor Mangona © Victor Leonard Slatkin Sergey RACHMANINOV (1873–1943) Symphony No. -

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Phyllis Curtin - Box 1 Folder# Title: Photographs Folder# F3 Clothes by Worth of Paris (1900) Brooklyn Academy F3 F4 P.C. recording F4 F7 P. C. concert version Rosenkavalier Philadelphia F7 FS P.C. with Russell Stanger· FS F9 P.C. with Robert Shaw F9 FIO P.C. with Ned Rorem Fl0 F11 P.C. with Gerald Moore Fl I F12 P.C. with Andre Kostelanetz (Promenade Concerts) F12 F13 P.C. with Carlylse Floyd F13 F14 P.C. with Family (photo of Cooke photographing Phyllis) FI4 FIS P.C. with Ryan Edwards (Pianist) FIS F16 P.C. with Aaron Copland (televised from P.C. 's home - Dickinson Songs) F16 F17 P.C. with Leonard Bernstein Fl 7 F18 Concert rehearsals Fl8 FIS - Gunther Schuller Fl 8 FIS -Leontyne Price in Vienna FIS F18 -others F18 F19 P.C. with hairdresser Nina Lawson (good backstage photo) FI9 F20 P.C. with Darius Milhaud F20 F21 P.C. with Composers & Conductors F21 F21 -Eugene Ormandy F21 F21 -Benjamin Britten - Premiere War Requiem F2I F22 P.C. at White House (Fords) F22 F23 P.C. teaching (Yale) F23 F25 P.C. in Tel Aviv and U.N. F25 F26 P. C. teaching (Tanglewood) F26 F27 P. C. in Sydney, Australia - Construction of Opera House F27 F2S P.C. in Ipswich in Rehearsal (Castle Hill?) F2S F28 -P.C. in Hamburg (large photo) F2S F30 P.C. in Hamburg (Strauss I00th anniversary) F30 F31 P. C. in Munich - German TV F31 F32 P.C. -

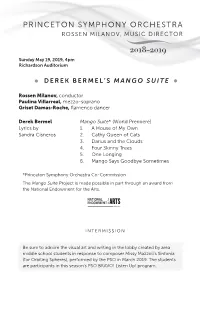

Mango Suite Program Pages

PRINCETON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ROSSEN MILANOV, MUSIC DIRECTOR 2018–2019 Sunday May 19, 2019, 4pm Richardson Auditorium DEREK BERMEL’S MANGO SUITE Rossen Milanov, conductor Paulina Villarreal, mezzo-soprano Griset Damas-Roche, flamenco dancer Derek Bermel Mango Suite* (World Premiere) Lyrics by 1. A House of My Own Sandra Cisneros 2. Cathy Queen of Cats 3. Darius and the Clouds 4. Four Skinny Trees 5. One Longing 6. Mango Says Goodbye Sometimes *Princeton Symphony Orchestra Co-Commission The Mango Suite Project is made possible in part through an award from the National Endowment for the Arts. INTERMISSION Be sure to admire the visual art and writing in the lobby created by area middle school students in response to composer Missy Mazzoli’s Sinfonia (for Orbiting Spheres), performed by the PSO in March 2019. The students are participants in this season’s PSO BRAVO! Listen Up! program. Manuel de Falla El amor brujo Introducción y escena (Introduction and Scene) En la cueva (In the Cave) Canción del amor dolido (Song of Love’s Sorrow) El Aparecido (The Apparition) Danza del terror (Dance of Terror) El círculo mágico (The Magic Circle) A medianoche (Midnight) Danza ritual del fuego (Ritual Fire Dance) Escena (Scene) Canción del fuego fatuo (Song of the Will-o’-the-Wisp) Pantomima (Pantomime) Danza del juego de amor (Dance of the Game of Love) Final (Finale) El sombrero de tres picos (The Three-Cornered Hat), Suite No. 1 Introduction—Afternoon Dance of the Miller’s Wife (Fandango) The Corregidor The Grapes La vida breve, Spanish Dance No. 1 This concert is made possible in part through the support of Yvonne Marcuse. -

Ross Bauer, Composer Portrait Celebrating His Sixtieth Birthday

Mika Pelo and Kurt Rohde, co-directors PeRFoRMeRS Hrabba atladottir, violin ellen Ruth Rose, viola Mary artmann, cello Michael Seth orland, piano Peter Josheff, clarinet eric Zivian, piano Jean-Michel Fonteneau, cello Ross Bauer, Composer Portrait Celebrating His Sixtieth Birthday 7:00 pm, Sunday, JanuaRy 22, 2012 Vanderhoef Studio Theatre, Robert and Margrit Mondavi Center for the Performing arts 6:15pm pre-ConCert TalK with composers Ross Bauer, Martha Horst, and Harold Meltzer EmpyRean enSemble Co-directors Mika Pelo Kurt Rohde PERFORMERS Hrabba Atladottir, violin Ellen Ruth Rose, viola Mary Artmann, cello Michael Seth Orland, piano Peter Josheff, clarinet Eric Zivian, piano Jean-Michel Fonteneau, cello adMinistraTiVe & PRoduction STaff Christina Acosta, editor Philip Daley, publicity manager Rudy Garibay, designer Joshua Paterson, production manager THe dePartmenT oF MuSiC preSents The empyrean ensemble Mika Pelo and Kurt Rohde, co-directors Ross Bauer Composer Portrait Program The Near Beyond for Clarinet and String Trio Ross Bauer (b. 1951) Pink Angels for Violin, Viola, and Violoncello Harold Meltzer (world premiere, in honor of Ross Bauer’s sixtieth birthday) (b. 1966) Riff Tides for Violin, Cello, Viola, Bass Clarinet Martha Horst (world premiere, in honor of Ross Bauer’s sixtieth birthday) (b. ) Tribute for Cello and Piano Ross Bauer intermission Sequenza IX for Solo Clarinet Luciano Berio (1925–2003) Piano Quartet Ross Bauer Moderato Adagio Allegro giocoso Please join us for a reception following the concert in the Bartholomew Room Sunday, January 22, 2012 • 7:00 pm Vanderhoef Studio Theatre, Mondavi Center We ask that you be courteous to your fellow audience members and the performers. -

News Release

news release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PRESS CONTACT: Maggie Stapleton, Jensen Artists September 25, 2019 646.536.7864 x2; [email protected] American Composers Orchestra Announces 2019-2020 Season Derek Bermel, Artistic Director & George Manahan, Music Director Two Concerts presented by Carnegie Hall New England Echoes on November 13, 2019 & The Natural Order on April 2, 2020 at Zankel Hall Premieres by Mark Adamo, John Luther Adams, Matthew Aucoin, Hilary Purrington, & Nina C. Young Featuring soloists Jamie Barton, mezzo-soprano; JIJI, guitar; David Tinervia, baritone & Jeffrey Zeigler, cello The 29th Annual Underwood New Music Readings March 12 & 13, 2020 at Aaron Davis Hall at The City College of New York ACO’s annual roundup of the country’s brightest young and emerging composers EarShot Readings January 28 & 29, 2020 with Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra May 5 & 6, 2020 with Houston Symphony Third Annual Commission Club with composer Mark Adamo to support the creation of Last Year ACO Gala 2020 honoring Anthony Roth Constanzo, Jesse Rosen, & Yolanda Wyns March 4, 2020 at Bryant Park Grill www.americancomposers.org New York, NY – American Composers Orchestra (ACO) announces its full 2019-2020 season of performances and engagements, under the leadership of Artistic Director Derek Bermel, Music Director George Manahan, and President Edward Yim. ACO continues its commitment to the creation, performance, preservation, and promotion of music by 1 American Composers Orchestra – 2019-2020 Season Overview American composers with programming that sparks curiosity and reflects geographic, stylistic, racial and gender diversity. ACO’s concerts at Carnegie Hall on November 13, 2019 and April 2, 2020 include major premieres by 2015 Rome Prize winner Mark Adamo, 2014 Pulitzer Prize winner John Luther Adams, 2018 MacArthur Fellow Matthew Aucoin, 2017 ACO Underwood Commission winner Hilary Purrington, and 2013 ACO Underwood Audience Choice Award winner Nina C. -

Stoltzmanresolve Digibooklet.Pdf

1 CONCERTO FOR CLARINET AND ORCHESTRA (1947) I. A wizardly weave of contrapuntal themes and rhythmic motives instantly engulfs us. The solo clarinet enters on the intervals that gave historic birth to the instrument: octave, fifth, and twelfth, its harmonic backbone. The theme creates a sweeping arch over seven measures long eloquently encompassing all the clarinet’s registers. The first movement coda ends with a twinkle as the clarinet giggles a bluesy trill; followed by a glockenspiel exclama- tion point and a timpani plop! I am reminded of my interview with Lukas Foss on his student memories of Hindemith at Tanglewood. “After class he took us down to the pond for a swim. I’ll never forget the sound of his plump little body landing in the water with a plop!” II. The ostinato takes a five note pizzicato pattern with a jazz syncopation before the fifth note. The groove slides over to another beat at each entrance making a simple steady 2/2 time excitingly elusive. Riding that groove is a rapid clarinet lick right out of the “King of Swing”’s bag. A rhythm section (timpani, snare drum, triangle, and tambourine) sets a “Krupa-like” complexity, and before you know it the ride ends with the band disappearing clean as a clarinet pianissimo. III. Perhaps the longest, most melancholic, beautiful melody ever written for the clarinet; twenty measures of breath- taking calm and majesty. Balancing this sweeping aria is a recitative (measures 51-71). Hindemith gives the return of the song to solo oboe surrounded by soft, tiny woodwind creatures and muted murmurings for two solo violins. -

CULTIVATE Five Emerging Composers Selected for Intensive, All-Scholarship Workshop and Mentoring Program; Derek Bermel Named Program Director

NEWS...For Immediate Release June 15, 2012 Contact: Elizabeth Dworkin, Dworkin & Company 914.244.3803, [email protected] Copland House Launches CULTIVATE Five Emerging Composers Selected for Intensive, All-Scholarship Workshop and Mentoring Program; Derek Bermel Named Program Director Cortlandt Manor, NY - Copland House today announces the launch of CULTIVATE, an intensive, annual, all-scholarship creative workshop and mentoring program dedicated to developing the talents of exceptionally gifted American composers in the initial stages of their professional careers. Serving as CULTIVATE Director is Derek Bermel, the acclaimed composer and Founding Clarinetist of the Music from Copland House ensemble. For the inaugural session this summer, five composers from around the U.S. have been invited to participate: Nathan Heidelberger, 25 (Westchester Community Foundation Valentine and Clark Fellow); Roger Zare, 27 (ASCAP Foundation Fellow); Michael Djupstrom, 31; Reena Esmail, 29; and Michael Ippolito, 27. "We hope that CULTIVATE will help these gifted young composers to be better prepared as creators, artists, and leaders in a profoundly-changing musical landscape," said Copland House's Artistic and Executive Director Michael Boriskin. "We intend for this program to contribute substantively to the essential discourse about the role of composers in today's shifting social, civic, and cultural environments. And having worked with Derek -as composer, performer, resident, educator, and general artistic partner, colleague, and friend- since Copland House first opened its doors in 1998, we know that he is singularly-equipped to oversee one of our most important new initiatives to support young composers." "I am excited about steering Copland House's CULTIVATE program," Bermel explained.