Mcallister Interview Transcription

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eastman School of Music, Thrill Every Time I Enter Lowry Hall (For- Enterprise of Studying, Creating, and Loving 26 Gibbs Street, Merly the Main Hall)

EASTMAN NOTESFALL 2015 @ EASTMAN Eastman Weekend is now a part of the University of Rochester’s annual, campus-wide Meliora Weekend celebration! Many of the signature Eastman Weekend programs will continue to be a part of this new tradition, including a Friday evening headlining performance in Kodak Hall and our gala dinner preceding the Philharmonia performance on Saturday night. Be sure to join us on Gibbs Street for concerts and lectures, as well as tours of new performance venues, the Sibley Music Library and the impressive Craighead-Saunders organ. We hope you will take advantage of the rest of the extensive Meliora Weekend programming too. This year’s Meliora Weekend @ Eastman festivities will include: BRASS CAVALCADE Eastman’s brass ensembles honor composer Eric Ewazen (BM ’76) PRESIDENTIAL SYMPOSIUM: THE CRISIS IN K-12 EDUCATION Discussion with President Joel Seligman and a panel of educational experts AN EVENING WITH KEYNOTE ADDRESS EASTMAN PHILHARMONIA KRISTIN CHENOWETH BY WALTER ISAACSON AND EASTMAN SCHOOL The Emmy and Tony President and CEO of SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Award-winning singer the Aspen Institute and Music of Smetana, Nicolas Bacri, and actress in concert author of Steve Jobs and Brahms The Class of 1965 celebrates its 50th Reunion. A highlight will be the opening celebration on Friday, featuring a showcase of student performances in Lowry Hall modeled after Eastman’s longstanding tradition of the annual Holiday Sing. A special medallion ceremony will honor the 50th class to commemorate this milestone. The sisters of Sigma Alpha Iota celebrate 90 years at Eastman with a song and ritual get-together, musicale and special recognition at the Gala Dinner. -

ST. LOUIS SYMPHONY DAVID ROBERTSON, CONDUCTOR Wednesday, March 29, 2017, at 7:30Pm Foellinger Great Hall PROGRAM ST

ST. LOUIS SYMPHONY DAVID ROBERTSON, CONDUCTOR Wednesday, March 29, 2017, at 7:30pm Foellinger Great Hall PROGRAM ST. LOUIS SYMPHONY David Robertson, music director and conductor John Adams The Chairman Dances, Foxtrot for Orchestra (1985) (b. 1947) Aaron Copland Appalachian Spring, Ballet Suite for Orchestra (1944) (1900–1990) 20-minute intermission Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No. 7 in A major, op. 92 (1812) (1770–1827) Poco sostenuto; Vivace Allegretto Presto; Assai meno Allegro con brio 2 THANK YOU TO THE SPONSORS OF THIS PERFORMANCE GIVING OF ACT THE Krannert Center honors the spirited generosity of these committed sponsors whose support of this performance continues to strengthen the impact of the arts in our community. Krannert Center honors the memory of Endowed Underwriters Marilyn Pflederer Zimmerman & Vernon K. Zimmerman. Their lasting investment in the performing arts and our community will allow future generations to experience world-class performances such as this one. * Krannert Center gratefully acknowledges the continued generosity of Endowed Sponsors Mary & Kenneth Andersen. With their previous sponsorships, they demonstrate their dedication to sharing beautiful and significant cultural events with our community. *PHOTO CREDIT: ILLINI STUDIO 3 * * JAMES ECONOMY HELEN & DANIEL RICHARDS Special Support of Classical Music Twenty-Seven Previous Sponsorships * * THE ACT OF GIVING OF ACT THE PEGGY MADDEN & MARY SCHULER & RICHARD PHILLIPS STEPHEN SLIGAR Fourteen Previous Sponsorships Five Previous Sponsorships Two Current Sponsorships -

Program Notes: Inspiration & Impact

CABRILLO FESTIVAL Program Notes: Inspiration & Impact Lola Montez Does the and she glides from the stage of sensory and expressive overload. Spider Dance (2016) overwhelmed with applause, At its premiere in March of 2012, the first third and smashed spiders, John Adams of the piece was largely a trope on the Opus (b. 1947) and radiant with parti-colored skirts, [World Premiere] 131 C# minor quartet’s scherzo and suffered smiles, graces, cobwebs and glory. from just this problem. After a moody opening of tremolo strings and fragments of the Ninth Commissioned by the musicians of the Cabrillo Lola Montez Does the Spider Dance was Symphony signal octave-dropping motive, Festival Orchestra in honor of Marin Alsop commissioned by members of the Cabrillo Festival Orchestra in celebration of Marin the solo quartet emerged as if out of a haze, The Irish-born actress and dancer Eliza Gilbert Alsop’s twenty five seasons as music director, playing the driving foursquare figures of that (1821—1861) achieved international fame and it is dedicated to her. scherzo material that almost immediately went under the name “Lola Montez, the Spanish through a series of strange permutations. Dancer.” After a controversial career on the —John Adams continent, including a sojourn in Bavaria This original opening never satisfied me. The where she become both the lover as well as clarity of the solo quartet’s role was often political advisor to King Ludwig, she returned Absolute Jest (2011) buried beneath the orchestral activity resulting in what sounded to me too much like “chatter.” to London, where she eloped with and married John Adams (b. -

Mahler 5 & Music You Know

CONCERT PROGRAM Friday, January 22, 2016, 10:30am Saturday, January 23, 2016, 8:00pm David Robertson, conductor Timothy McAllister, saxophone JOHN ADAMS Saxophone Concerto (2013) (b. 1947) Animato; Moderato; Tranquillo, suave Molto vivo (a hard driving pulse) Timothy McAllister, saxophone INTERMISSION MAHLER Symphony No. 5 in C-sharp minor (1901-02) (1860-1911) PART I Trauermarsch. In gemessenem Schritt. Streng. Wie ein Kondukt Stürmisch bewegt, mit größter Vehemenz PART II Scherzo. Kräftig, nicht zu schnell PART III Adagietto. Sehr langsam— Rondo-Finale. Allegro 23 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS These concerts are part of the Wells Fargo Advisors Orchestral series. These concerts are presented by St. Louis College of Pharmacy. David Robertson is the Beofor Music Director and Conductor. Timothy McAllister is the Ann and Paul Lux Guest Artist. The concert of Saturday, January 23, is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Rex and Jeanne Sinquefield. The concert of Friday, January 22, 10:30am, features coffee and doughnuts provided through the generosity of Community Coffee and Krispy Kreme, respectively. Pre-Concert Conversations are sponsored by Washington University Physicians. Large print program notes are available through the generosity of Bellefontaine Cemetery and Arboretum and are located at the Customer Service table in the foyer. 24 ON EDGE BY EDDIE SILVA Their music is made of the worlds around them, Gustav Mahler and John Adams. Mahler of that thrilling age, the shift from the 19th to the 20th century, the speed of the modern beginning to TIMELINKS change how people think and act. Also a time of anxiety, especially for a Jewish artist in an anti- Semitic Vienna. -

Joana Carneiro Music Director

JOANA CARNEIRO MUSIC DIRECTOR Berkeley Symphony 17/18 Season 5 Message from the Music Director 7 Message from the Board President 9 Message from the Executive Director 11 Board of Directors & Advisory Council 12 Orchestra 15 Season Sponsors 16 Berkeley Sound Composer Fellows & Full@BAMPFA 18 Berkeley Symphony 17/18 Calendar 21 Tonight’s Program 23 Program Notes 37 About Music Director Joana Carneiro 39 Guest Artists & Composers 43 About Berkeley Symphony 44 Music in the Schools 47 Berkeley Symphony Legacy Society 49 Annual Membership Support 58 Broadcast Dates 61 Contact 62 Advertiser Index Media Sponsor Gertrude Allen • Annette Campbell-White & Ruedi Naumann-Etienne Official Wine Margaret Dorfman • Ann & Gordon Getty • Jill Grossman Sponsor Kathleen G. Henschel & John Dewes • Edith Jackson & Thomas W. Richardson Sarah Coade Mandell & Peter Mandell • Tricia Swift S. Shariq Yosufzai & Brian James Presentation bouquets are graciously provided by Jutta’s Flowers, the official florist of Berkeley Symphony. Berkeley Symphony is a member of the League of American Orchestras and the Association of California Symphony Orchestras. No photographs or recordings of any part of tonight’s performance may be made without the written consent of the management of Berkeley Symphony. Program subject to change. October 5 & 6, 2017 3 4 October 5 & 6, 2017 Message from the Music Director Dear Friends, Happy New Season 17/18! I am delighted to be back in Berkeley after more than a year. There are three beautiful reasons for photo by Rodrigo de Souza my hiatus. I am so grateful for all the support I received from the Berkeley Symphony musicians, members of the Board and Advisory Council, the staff, and from all of you throughout this special period of my family’s life. -

THE CLEVELAN ORCHESTRA California Masterwor S

����������������������� �������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������ �������������������������������������� �������� ������������������������������� ��������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������� �������������������� ������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������ ������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������� ����������������������������� ����� ������������������������������������������������ ���������������� ���������������������������������������� ��������������������������� ���������������������������������������� ��������� ������������������������������������� ���������� ��������������� ������������� ������ ������������� ��������� ������������� ������������������ ��������������� ����������� �������������������������������� ����������������� ����� �������� �������������� ��������� ���������������������� Welcome to the Cleveland Museum of Art The Cleveland Orchestra’s performances in the museum California Masterworks – Program 1 in May 2011 were a milestone event and, according to the Gartner Auditorium, The Cleveland Museum of Art Plain Dealer, among the year’s “high notes” in classical Wednesday evening, May 1, 2013, at 7:30 p.m. music. We are delighted to once again welcome The James Feddeck, conductor Cleveland Orchestra to the Cleveland Museum of Art as this groundbreaking collaboration between two of HENRY COWELL Sinfonietta -

Orfeo Euridice

ORFEO EURIDICE NOVEMBER 14,17,20,22(M), 2OO9 Opera Guide - 1 - TABLE OF CONTENTS What to Expect at the Opera ..............................................................................................................3 Cast of Characters / Synopsis ..............................................................................................................4 Meet the Composer .............................................................................................................................6 Gluck’s Opera Reform ..........................................................................................................................7 Meet the Conductor .............................................................................................................................9 Meet the Director .................................................................................................................................9 Meet the Cast .......................................................................................................................................10 The Myth of Orpheus and Eurydice ....................................................................................................12 OPERA: Then and Now ........................................................................................................................13 Operatic Voices .....................................................................................................................................17 Suggested Classroom Activities -

Form in the Music of John Adams

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Ridderbusch, Michael, "Form in the Music of John Adams" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6503. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6503 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch DMA Research Paper submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Theory and Composition Andrew Kohn, Ph.D., Chair Travis D. Stimeling, Ph.D. Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Cynthia Anderson, MM Matthew Heap, Ph.D. School of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2017 Keywords: John Adams, Minimalism, Phrygian Gates, Century Rolls, Son of Chamber Symphony, Formalism, Disunity, Moment Form, Block Form Copyright ©2017 by Michael Ridderbusch ABSTRACT Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch The American composer John Adams, born in 1947, has composed a large body of work that has attracted the attention of many performers and legions of listeners. -

FRENCH SYMPHONIES from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

FRENCH SYMPHONIES From the Nineteenth Century To The Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman NICOLAS BACRI (b. 1961) Born in Paris. He began piano lessons at the age of seven and continued with the study of harmony, counterpoint, analysis and composition as a teenager with Françoise Gangloff-Levéchin, Christian Manen and Louis Saguer. He then entered the Paris Conservatory where he studied with a number of composers including Claude Ballif, Marius Constant, Serge Nigg, and Michel Philippot. He attended the French Academy in Rome and after returning to Paris, he worked as head of chamber music for Radio France. He has since concentrated on composing. He has composed orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. His unrecorded Symphonies are: Nos. 1, Op. 11 (1983-4), 2, Op. 22 (1986-8), 3, Op. 33 "Sinfonia da Requiem" (1988-94) and 5 , Op. 55 "Concerto for Orchestra" (1996-7).There is also a Sinfonietta for String Orchestra, Op. 72 (2001) and a Sinfonia Concertante for Orchestra, Op. 83a (1995-96/rév.2006) . Symphony No. 4, Op. 49 "Symphonie Classique - Sturm und Drang" (1995-6) Jean-Jacques Kantorow/Tapiola Sinfonietta ( + Flute Concerto, Concerto Amoroso, Concerto Nostalgico and Nocturne for Cello and Strings) BIS CD-1579 (2009) Symphony No. 6, Op. 60 (1998) Leonard Slatkin/Orchestre National de France ( + Henderson: Einstein's Violin, El Khoury: Les Fleuves Engloutis, Maskats: Tango, Plate: You Must Finish Your Journey Alone, and Theofanidis: Rainbow Body) GRAMOPHONE MASTE (2003) (issued by Gramophone Magazine) CLAUDE BALLIF (1924-2004) Born in Paris. His musical training began at the Bordeaux Conservatory but he went on to the Paris Conservatory where he was taught by Tony Aubin, Noël Gallon and Olivier Messiaen. -

Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Friday Evening, February 20, 2015, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium/Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor MAX VON SCHILLINGS Mona Lisa ACT I Intermission ACT II Foreigner/Francesco del Giocondo: MICHAEL ANTHONY MCGEE, Bass-baritone Woman/Mona Fiordalisa: PETRA MARIA SCHNITZER, Soprano Lay Brother/Giovanni de Salviati: PAUL MCNAMARA, Tenor Pietro Tumoni: JUSTIN HOPKINS, Bass-baritone Arrigo Oldofredi: ROBERT CHAFIN, Tenor Alessio Beneventi: JOHN EASTERLIN, Tenor Sandro da Luzzano: CHRISTOPHER BURCHETT, Baritone Masolino Pedruzzi: MICHAEL SCARCELLE, Bass-baritone Mona Ginevra: ILANA DAVIDSON, Soprano Dianora: LUCY FITZ GIBBON, Soprano Piccarda: KATHERINE MAYSEK, Mezzo-soprano Sisto: JOHN KAWA, Tenor BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director This evening’s concert will run approximately two hours and 20 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. Used by arrangement with European American Music Distributors Company, sole U.S. and Canadian agent for Universal Edition Vienna, publisher and copyright owner. American Symphony Orchestra welcomes the many organizations who participate in our Community Access Program, which provides free and low-cost tickets to underserved groups in New York’s five boroughs. For information on how you can support this program, please call (212) 868-9276. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. FROM THE Music Director The Stolen Smile DVDs or pirated videos. Opera is the by Leon Botstein one medium from the past that resists technological reproduction. A concert This concert performance of Max von version still represents properly the Schillings’ 1915 Mona Lisa is the latest sonority and the multi-dimensional installment of a series of concert perfor- aspect crucial to the operatic experi- mances of rare operas the ASO has pio- ence. -

Kajian Tentang Karakteristik Permainan Musik Saxophone Kaori Kobayashi

i EKSPRESI MUSIKAL: KAJIAN TENTANG KARAKTERISTIK PERMAINAN MUSIK SAXOPHONE KAORI KOBAYASHI SKRIPSI disajikan Sebagai Salah Satu Syarat Untuk Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Pendidikan Jurusan Pendidikan Seni Drama, Tari, dan Musik oleh Nama : Garin Ria Sukmawati NIM : 2501411144 Program Studi : Pendidikan Seni Musik Jurusan : Pendidikan Seni Drama Tari dan Musik FAKULTAS BAHASA DAN SENI UNIVERSITAS NEGERI SEMARANG 2016 ii ii iii iii iv PERNYATAAN KEASLIAN SKRIPSI Dengan ini saya, Nama : Garin Ria Sukmawati NIM : 2501411144 Program Studi : Pendidikan Seni Musik (S1) Jurusan : Pendidikan Seni Drama, Tari, dan Musik Fakultas : Bahasa dan Seni Universitas Negeri Semarang Judul Skripsi : Ekspresi Musikal: Kajian Tentang Karakteristik Permainan Musik Saxophone Kaori Kobayashi Menyatakan dengan sebenarnya bahwa skripsi yang saya serahkan ini benar-benar hasil karya saya sendiri, kecuali kutipan dan ringkasan yang semua sumbernya telah saya jelaskan. Apabila di kemudian hari terbukti atau dapat dibuktikan bahwa skripsi ini hasil jiplakan, maka gelar dan ijazah yang diberikan oleh Universitas Negeri Semarang batal saya terima. Yang membuat pernyataan, Semarang, 2016 Garin Ria Sukmawati NIM. 2501411144 iv v MOTTO DAN PERSEMBAHAN 1. Yang meninggalkan derajat seseorang ialah akal dan adabnya, bukan asal keturunanya (Aristoteles) 2. Orang yang emosional biasanya kurang rasional sehingga tindakanya tidak profesional. (Mario Teguh) 3. Kemenangan yang paling indah adalah bisa menaklukkan hati sendiri. (La Fontaine) Skripsi ini kupersembahkan untuk: Bp. Mulyo Prasodjo dan Ibu Purmiasih Pendidikan Sendratasik Angkatan 2011 Segenap Dosen Pendidikan Sendratasik v vi KATA PENGANTAR Puji syukur peneliti panjatkan kedalam tangan kuasa Tuhan Yesus Kristus yang telah melimpahkan anugerahnya sehingga akhirnya penulis dapat menyelesaikan penyusunan skripsi yang berjudul “Ekspresi Musikal: Kajian Tentang Karakteristik Permainan Musik Saxophone Kaori Kobayashi”. -

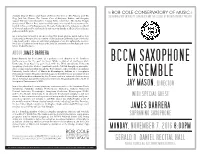

Bccm Saxophone Ensemble

Aladdin King of Thieves and Tower of Terror, Toy Story 3, The Princess and The Frog, Just Like Heaven, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, and Gangster Squad. Television credits include Dragon Tales, Child Star: The Shirley Temple Story, several Warner Bros. cartoons and many commercials for companies like United Airlines and Kellogg Cereals. He is also featured on the video games World of Warcraft and Diablo, and can be heard on soundtracks at all the Disney Theme parks around the globe. Jay is a member of Gordon Goodwin’s Big Phat Band, and the bands led by Tom Kubis and Les Hooper. He is a member of the faculty at California State University, Long Beach and is active as a clinician and guest artist throughout the country. He is also a Vandoren Reed Artist and Clinician, and endorses RooPads and other Music Medic Products. ABOUT JAMES BARRERA James Barrera has been active as a performer and educator in the Southern BCCM SAXOPHONE California area for the past 15 years. While a student at California State University, Long Beach he performed with the Wind Symphony, University Symphony Orchestra, Studio I Jazz Band, and the CSULB Saxophone Ensemble. After completing his BM in Saxophone Performance, James attended the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music in Bloomington, Indiana as a Saxophone Performance Major. He performed throughout the Midwest as a member of the ENSEMBLE IU Wind Ensemble conducted by Ray Cramer, and as a featured soloist at many North American Saxophone Alliance conferences. He graduated with a M.M. in Saxophone Performance in 2003.