University of Groningen German Migration to Groningen And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HW&Co. Industry Reader Template

EUROPEAN UPDATE INDUSTRY UPDATE │ SUMMER 2015 www.harriswilliams.com www.harriswilliams.de Harris Williams & Co. Ltd is a private limited company incorporated under English law having its registered office at 5th Floor, 6 St. Andrew Street, London EC4A 3AE, UK, registered with the Registrar of Companies for England and Wales under company number 7078852. Directors: Mr. Christopher Williams, Mr. Ned Valentine, Mr. Paul Poggi and Mr. Thierry Monjauze, authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Harris Williams & Co. Ltd Niederlassung Frankfurt (German branch) is registered in the Commercial Register (Handelsregister) of the Local Court (Amtsgericht) of Frankfurt am Main, Germany, under registration number HRB 96687, having its business address at Bockenheimer Landstrasse 33-35, 60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany. Permanent Representative (Ständiger Vertreter) of the Branch Niederlassung: Mr. Jeffery H. Perkins. EUROPEAN UPDATE INDUSTRY UPDATE │ SUMMER 2015 HARRIS WILLIAMS & CO. CONTACTS CONTENTS Thierry Monjauze Managing Director QUARTERLY QUICK READ 63 Brook Street London W1K 4HS United Kingdom EUROPEAN ECONOMIC CLIMATE Phone: +44 20 7518 8901 [email protected] EUROPEAN M&A ENVIRONMENT Red Norrie Managing Director EUROPEAN INBOUND M&A ENVIRONMENT 63 Brook Street London W1K 4HS United Kingdom AEROSPACE, DEFENCE & GOVERNMENT SERVICES Phone: +44 20 7518 8906 [email protected] BUSINESS SERVICES Jeffery Perkins Managing Director CONSUMER Bockenheimer Landstr. 33-35 60325 Frankfurt Germany ENERGY & POWER Phone: +49 69 3550638 00 [email protected] HEALTHCARE & LIFE SCIENCES LONDON OFFICE 63 Brook Street INDUSTRIALS London W1K 4HS United Kingdom Phone: +44 20 7518 8900 TECHNOLOGY, MEDIA & TELECOM FRANKFURT OFFICE Bockenheimer Landstrasse TRANSPORTATION & LOGISTICS 33-35 60325 Frankfurt am Main Germany FEATURED THEME Phone: +49 69 3650638 00 FEATURED THEME – MOMENTUM IN ACQUISITIONS BY STRATEGIC BUYERS1 . -

The War and Fashion

F a s h i o n , S o c i e t y , a n d t h e First World War i ii Fashion, Society, and the First World War International Perspectives E d i t e d b y M a u d e B a s s - K r u e g e r , H a y l e y E d w a r d s - D u j a r d i n , a n d S o p h i e K u r k d j i a n iii BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA 29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2021 Selection, editorial matter, Introduction © Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian, 2021 Individual chapters © their Authors, 2021 Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Editors of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on p. xiii constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design by Adriana Brioso Cover image: Two women wearing a Poiret military coat, c.1915. Postcard from authors’ personal collection. This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third- party websites referred to or in this book. -

4.4-2 Lower Saxony WS Region.Pdf

chapter4.4_Neu.qxd 08.10.2001 16:11 Uhr Seite 195 Chapter 4.4 The Lower Saxony Wadden Sea Region 195 near Sengwarden have remained fully intact. The With the exception of the northern section’s water tower on „Landeswarfen“ west of tourist visitors, the Voslapper Groden mainly Hohenkirchen is a landmark visible from a great serves as a sea rampart for Wilhelmshaven’s distance, constructed by Fritz Höger in 1936 to commercial buildings, a function also served by serve as Wangerooge’s water supply. the Rüstersieler Groden (1960-63) and the Hep- Of the above-mentioned scattered settlements penser Groden, first laid out as a dyke line from characteristic to this region, two set themselves 1936-38, although construction only started in physically apart and therefore represent limited 1955. It remains to be seen whether the histori- forms within this landscape. cally preserved parishes of Sengwarden and Fed- Some sections of the old dyke ring whose land derwarden, now already part of Wilhelmshaven, was considered dispensable from a farming or will come to terms with the consequences of this land ownership perspective served as building and the inexorable urban growth through appro- space for erecting small homes of farm labourers priate planning. and artisans who otherwise made their homes in The cultural landscape of the Wangerland and small numbers on larger mounds. Among these the Jeverland has been able to preserve its were the „small houses“ referred to in oral tradi- unmistakable character to a considerable degree. tion north of Middoge, the Oesterdeich (an early The genesis of landscape forms is mirrored in the groden dyke), the Medernser Altendeich, the patterns of settlement, the lay of arable land and Norderaltendeich and foremost the area west of in landmark monuments. -

Population by Area/Community Churches

Ostfriesen Genealogical Society of America OGSA PO Box 50919 Mendota, MN 55150 651-269-3580 www.ogsa.us 1875 Ostfriesland Census Detail The 1875 census provided insights into the communities and neighborhoods across Ostfriesland. The following table is sorted by Amt (Church district) and Kirchspiel (Church community) or location if the enumerated area does not have its own Church. Region Religion Town/Area Denomination Amt Kirchspiel / Location Lutheran Reformed Catholic Other Jewish Total Christian Aurich Lutheran, Aurich Aurich 3,569 498 282 106 364 4,819 Reformed, Catholic Plaggenburg Lutheran Aurich Aurich 529 40 4 573 Dietrichsfeld Aurich Aurich 201 6 207 Egels Aurich Aurich 235 1 7 243 Ertum Aurich Aurich 337 8 345 Georgßfeld Aurich Aurich 88 4 2 94 Hartum Aurich Aurich 248 18 9 275 Ihlow Aurich Weene 6 6 Kirchdorf Aurich Aurich 527 15 1 3 546 Meerhusen Aurich Aurich 9 9 Pfalsdorf Aurich Aurich 119 41 160 Popens Aurich Aurich 127 4 131 Rahe Aurich Aurich 268 25 3 296 Sandhorst Aurich Aurich 643 48 8 7 706 Tannenhausen Aurich Aurich 337 16 353 © 2018: Ostfriesen Genealogical Society of America 1 1875 Ostfriesland Census Detail Region Religion Town/Area Denomination Amt Kirchspiel / Location Lutheran Reformed Catholic Other Jewish Total Christian Walle Aurich Aurich 779 33 812 Wallinghausen Aurich Aurich 408 17 425 Ostgroßefehn Lutheran Aurich Aurich, Oldendorf 1,968 33 1 28 7 2,037 Aurich-Oldendorf Lutheran Aurich Aurich-Oldendorf 754 4 1 4 1 764 Spetzerfehn Lutheran Aurich Aurich-Oldendorf, 988 1 989 Bagband, Strackholt Bagband -

Regionales Raumordnungsprogramm 2006 - Teil II –

Landkreis Leer Regionales Raumordnungsprogramm 2006 Regionales Raumordnungsprogramm – Vorwort Landkreis Leer Vorwort Das Regionale Raumordnungsprogramm (RROP) soll "den Raum Landkreis Leer ordnen" und legt neben dem Landesraumordnungsprogramm Ziele und Grundsätze fest. Die unter- schiedlichen Nutzungsansprüche an die Fläche sollen so möglichst aufeinander abgestimmt werden. Das Niedersächsische Raumordnungsgesetz schreibt dazu vor, dass die Planungen die nachhaltige Entwicklung des Landes und seiner Teile unter Beachtung der naturräumlichen und sonstigen Gegebenheiten in einer Weise fördern sollen, die der Gesamtheit und dem Einzelnen am besten dient. Dabei müssen die „Anforderungen zur Sicherung, des Schutzes, der Pflege und der Entwicklung der natürlichen Lebensgrundlagen sowie der sozialen, kultu- rellen und wirtschaftlichen Erfordernisse“ berücksichtigt werden. Damit das Raumordnungsprogramm für den Landkreis Leer dieses Ziel erreichen konnte, waren umfangreiche Vorarbeiten sowie ungezählte Abstimmungsgespräche und Beratungen, vor allem mit den Städten und Gemeinden sowie mit der Landwirtschaft, notwendig. Kreis- verwaltung und Kreistag war es während des gesamten Entstehungsprozesses des RROP ein besonderes Anliegen, mit den besonders Betroffenen schon im Vorfeld eine möglichst breite Übereinstimmung zu erzielen. Dass dies gelungen ist, machen der breite politische Konsens im Kreistag und die von Anfang an zu erkennende große Akzeptanz für das RROP deutlich. Es ist eine gute Basis, um gemeinsam die Entwicklung des Landkreises Leer vo- ranzubringen. Um die heutigen strukturpolitischen Herausforderungen zu bewältigen, sind vielfältige Pla- nungen auf ganz unterschiedlichen Ebenen durchzuführen. Dabei gestalten sich Abwä- gungs- und Entscheidungsprozesse angesichts ständig zunehmender verfahrensrechtlicher Anforderungen immer komplexer. Entscheidende Voraussetzung für die Nachhaltigkeit ein- zelner Handlungsmaßnahmen und damit für die weitere positive Entwicklung des Landkrei- ses ist es, diese auf ein gemeinsames gesamträumliches Leitbild auszurichten. -

How to Become a Loyalist: Petitions, Self-Fashioning, and the Repression of Unrest (East Frisia, 1725–1727)

How to Become a Loyalist: Petitions, Self-Fashioning, and the Repression of Unrest (East Frisia, 1725–1727) David M. Luebke N January 21, 1727, several communes in the Nordbrookmerland region of East Frisia, a small principality located on the North Sea coast of Germany and hard by the Dutch border, were granted what O 1 amounted to immunity from prosecution for acts of rebellion. How and why this happened is a story that has a great deal to tell about the influence ordi- nary people could exert, through petitioning, on the practice of state power in early modern Europe. In the months and years before 1727, the prince of East Frisia, Georg Albrecht, had become embroiled in an increasingly hostile confrontation with the Estates of his province for control over the administration of taxes in the land. In their efforts to gain the upper hand, both the prince and the Estates had tried to forge alliances among the rural population and mobilized these networks against each other. The Nordbrookmerlanders tended to ally with the prince, but felt increasingly isolated and endangered. Throughout the autumn of 1726, they had been petitioning the chancellor, Enno R. Brenneysen, for protection against attacks perpetrated by the Estates’ allies on their “wives and children, houses and farms.”2 In light of the chancellor’s inabil- ity to preserve them from further destruction, the village elders asked that they be allowed to obey the Estates’ commands until order was restored. Doing this, they pointed out, would force them to commit several “rebellious” acts, such 1 See a marginal notation in the hand of Chancellor Enno R. -

Rheiderland Zwischen Der Ems Und Den Niederlanden Unterkünfte Und Urlaubsinformationen 2021

Rheiderland Zwischen der Ems und den Niederlanden Unterkünfte und Urlaubsinformationen 2021 www.rheiderland-tourismus.de Orte Im Rheiderland Moin, 3 Rheiderland und herzlich willkommen im Rheiderland, dem wunderschönen Fleck- chen Erde zwischen der Ems und den Niederlanden im Feriengebiet erkunden »Südliches Ostfriesland«. Das Rheiderland, das sind die Gemeinden Bunde und Jemgum und die Stadt Weener. Sie alle bezaubern durch ihre fantastische Lage, ihr Freizeitangebot, ihre Gastfreundschaft und 6 hervorragende Übernachtungsmöglichkeiten. Ob Erholung, Radfahren oder Aktivurlaub auf dem Wasser - das Rheiderland bietet abwechs- Unterkünfte im lungsreiche Angebote. Sehr gut ausgeschilderte Radwegenetze und eine leichte Meeresbrise in der Nase machen jeden Urlaub zu einem Erlebnis. Rheiderland Lassen Sie sich überraschen! Gerne planen und organisieren wir nach Ihren Wünschen 10 Ihren Urlaub im Rheiderland. Impressum Herausgeber: Gemeinden des Rheiderland | Redaktion: Maren Baumann, Nadja Schiller, Sandra Brandt Gestaltung und Druckservice: Kleine Setzerei GmbH, 26817 Rhauderfehn Drucklegung: Dezember 2020 | Titelfoto: Tourist-Information Bunde Fotos: Tourist Information Weener, Tourist-Information Jemgum, Tourist-Information Bunde; www.ostfriesland.travel, Lars Klemmer Karten: art-studio Manitzke Rhauderfehn Die Preise entsprechen dem Stand der Drucklegung. 2 Kontakt Tourist-Information Bunde Kirchring 2, 26831 Bunde Tel. 049 53 / 8 09-47 [email protected] www.gemeinde-bunde.de bunde.eu Bunde Typisch ostfriesisch Der staatlich anerkannte Erholungsort Bunde mühlen steht im Ortskern von Bunde und die mit seinen vielen kleinen Ortschaften im ty- Wasserschöpfmühle Wynhamster Kolk steht pisch-ostfriesischen Stil liegt direkt am Dollart im Ortsteil Dollart an einer der tiefsten Stellen Steinhaus Bunderhee und der niederländischen Grenze. Die Gegend Deutschlands. mit seiner ursprünglichen Natur lockt sowohl Mit dem Steinhaus in Naturliebhaber, als auch Kulturinteressierte Im Hochmoor des Landschaftsschutzgebietes Bunderhee steht in der an. -

RP325 Cohn Marion R.Pdf

The Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People Jerusalem (CAHJP) PRIVATE COLLECTION MARION R. COHN – P 325 Xeroxed registers of birth, marriage and death Marion Rene Cohn was born in 1925 in Frankfurt am Main, Germany and raised in Germany and Romania until she immigrated to Israel (then Palestine) in 1940 and since then resided in Tel Aviv. She was among the very few women who have served with Royal British Air Forces and then the Israeli newly established Air Forces. For many years she was the editor of the Hasade magazine until she retired at the age of 60. Since then and for more than 30 years she has dedicated her life to the research of German Jews covering a period of three centuries, hundreds of locations, thousands of family trees and tens of thousands of individuals. Such endeavor wouldn’t have been able without the generous assistance of the many Registors (Standesbeamte), Mayors (Bürgermeister) and various kind people from throughout Germany. Per her request the entire collection and research was donated to the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People in Jerusalem and the Jewish Museum in Frankfurt am Main. She passed away in 2015 and has left behind her one daughter, Maya, 4 grandchildren and a growing number of great grandchildren. 1 P 325 – Cohn This life-time collection is in memory of Marion Cohn's parents Consul Erich Mokrauer and Hetty nee Rosenblatt from Frankfurt am Main and dedicated to her daughter Maya Dick. Cohn's meticulously arranged collection is a valuable addition to our existing collections of genealogical material from Germany and will be much appreciated by genealogical researchers. -

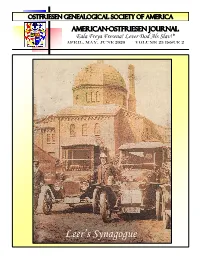

Leer's Synagogue

OSTFRIESEN GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA AMERICAN-OSTFRIESEN journal Eala Freya Fresena! Lever Dod Als Slav!* April, May, June 2020 Volume 23 issue 2 Leer’s Synagogue AMERICAN–Ostfriesen journal OGSA MEMBERSHIP Ostfriesen Genealogical Society of America MEMBER PRIVILEGES include four issues of the American- Eala Freya Fresena! Lever Dod Als Slav! Ostfriesen Journal (January, April, July, October), four program Volume 23Issue 2 April-June, 2020 meetings each year and one special event, special member order discounts, and access to the OGSA library. The journal of the Ostfriesen Genealogical Society of America is pub- OGSA 2020 MEMBERSHIP—Send your check for $22 (to lished four times a year. Please write: Lin Strong, Editor, OGSA download from our website or have sent as a pdf attachment to Newsletter, 15695-368th Street, Almelund, MN 55012 or email - OGSA, P.O. Box [email protected] with comments or suggestions. an email) or $32 for paper copies payable to 50919, Mendota Heights, MN 55150. Note that if you purchase a We are happy to consider any contributions of genealogical informa- paper copy, you can also have the codes for the online color tion. Whether we can use your material is based on such factors as copy! Just ask! general interest to our members, our need to cover certain subjects, Foreign membership is $22 if downloaded or sent by pdf file. balance through the year and available space. The editor reserves the right to edit all submitted materials for presentation and grammar. The You can deposit your membership at Sparkasse in Emden, Ger- editor will correct errors and may need to determine length of copy. -

NSA/OF/Ports (Aug.).Pages

Niedersachsen/Bremen/Hamburg/Ostfriesland Resources Introduction to Lower Saxony, Bremen & Hamburg Wikipedia states in regard to the regions of this modern German Bundesland: “Lower Saxony has clear regional divisions that manifest themselves both geographically as well as historically and culturally. In the regions that used to be independent, especially the heartlands of the former states of Brunswick, Hanover, Oldenburg and Schaumburg- Lippe, there is a marked local regional awareness. By contrast, the areas surrounding the Hanseatic cities of Bremen and Hamburg are much more oriented towards those centres.” A number of the Map Guides to German Parish Registers will need to be used to find your town if you are studying this region, among them numbers 4 (Oldenburg), 10 (Hessen-Nassau), 27 (Brunswick), 30-32 (Hannover), 39 (Westphalia & Schaumburg- Lippe) Online (a sampling) Niedersächsische Landesarchiv — http://aidaonline.niedersachsen.de Oldenburg emigrants — http://www.auswanderer-oldenburg.de Ahnenforschung.org “Regional Research” — http://forum.genealogy.net Hamburg Gen. Soc. — http://www.genealogy.net/vereine/GGHH/ Osnabrück Genealogical Society (German) — http://www.osfa.de Bremen’s “Mouse” Gen. Soc. (German) — http://www.die-maus-bremen.de/index.php Mailing Lists (for all German regions, plus German-speaking areas in Europe) -- http://list.genealogy.net/mm/listinfo/ Periodicals IGS/German-American Genealogy: “Niedersachsen Research,” by Eliz. Sharp (1990) “Niedersächsische Auswanderer in den U.S.A.” (Spr’98) “Researching Church -

The Old Country

Back to the Old Country A Sierra Vista Genie Club Presentaon By Agnes Gromek 2 January 2013 hBp://genealogy.about.com • This is your number one place to begin. • Before you pick out a country, check out the Lan word lists. Research your European ancestors with these free genealogy databases, records, and resources. Pick a country! . Austria (19) Belgium (10) Bri:sh Isles (244) Denmark England France (35) Finland Germany (47) Greece (12) Ireland Genealogy Italy (22) Lithuania (7) Netherlands (15) Norway Poland (28) Portugal (7) Russia (11) Scandinavia (78) Scotland Genealogy Spain (8) Sweden Switzerland (8) Ukraine (13) Wales Genealogy German Genealogy & Family History • Research your German ancestry with this collec:on of records and resources, including tutorials on German genealogy research, German surnames and naming customs, German dic:onaries and translaon, the Palane migraon, Hamburg and other passenger lists and free online German genealogy databases. Databases & Records (1) Emigraon & Ship Lists (11) Maps and Geography of Germany Socie:es & Organizaons (3) Related: German History Related: German Dic:onaries Related: Visi:ng Germany hp://feeas.org/ • FEEFHS The Federaon of East European Family History Socie:es • This is your number two place to get a feel for your country and what resources are available. • Don’t be surprised to find even western Germany and the Netherlands on here! Hanover, Prussia 1882 The Austrian Census for Galicia • 1880 Austrian Census Column Headings • Column IX – Language. There were eight acceptable languages: German, Ukrainian, Polish, Slovenian, Serbo-Croaan, Italian, Romanian, Tschekish-Moravian-Slovakian. hBp://www.archives.com/ How To Research Foreign Records Without Leaving Home by Lisa Alzo | Sep 20, 2011 She does a concise list of how to start, beginning with www.familysearch.org Her number two recommendaHon is to join an ethnic genealogical society. -

Landschaftspolder, Gemeinde Bunde, Landkreis Leer

Hartmut Rebuschat Landschaftspolder , Gemeinde Bunde, Landkreis Leer 1. Lage und Siedlungsform Landschaftspolder liegt in einem eingedeichten Polder zwischen der niederländischen Aa im Süden und der alten Flussmarsch der Ems im Norden in einer Höhe von 0,5 bis ca. 2 m über NN. Es handelt sich um einen sehr ertragsfähigen, mineralischen Boden mit besonders hohem Kalkgehalt und einer Bonität von 90 bis 93 Bodenpunkten. Das Dorf wurde entlang eines künstlichen Wasserzugs als Reihensiedlung angelegt. 2. Vor- und Frühgeschichte 1992 wurde am Bunder-Interessenten-Deich eine Geweihaxt aus dem Geweih eines erlegten Rothirsches aus dem Mesolithikum oder der jüngeren Bronzezeit oder gefunden. 3. Ortsname Vor dem Anwachs wurde der Bezirk als „Wynhamster Außendeich“ bezeichnet. Der Anwachs wurde „Bunder Anwachs“ genannt. Nach der Einpolderung entwickelte sich die ursprüngliche Bezeichnung von „Neuer Bunder Polder“ über „Preußenpolder“, „Friedrichspolder“ und „Königspolder“ ab 1756 – nach dem Verkauf an die Ostfriesische Landschaft– zu „neuer landschaftlicher Polder“, „Preußischer Landschaftspolder“ und schließlich zur heutigen Bezeichnung „Landschaftspolder“. 4. Geschichtlicher Überblick a. Entwicklung der Gemeinde bis zur Weimarer Republik 100 Jahre nach den größten Landverlusten durch die Dollarteinbrüche in Folge der Sturmfluten von 1509-1511 wurde 1605 mit der Eindeichung von Bunderneuland begonnen. 1682 folgte Charlottenpolder, 1707 Süderpolder, Norder-Christian-Eberhards-Polder und Bunder Interessentenpolder. 1752 wurde unter Friedrich dem Großen mit dem „neuen Bunder Polder“ der größte, 1225 ha umfassende Polder Ostfrieslands eingedeicht. Von Süd nach Nord zog man in der rechnerischen Mitte des Polders einen 7 km langen Weg mit einem Tief als Wasserzug. 24 große Höfe mit Graften, Obstgärten und viel Baumwuchs wurden in gleichmäßigem Abstand auf der südöstlichen Seite errichtet.