Reading Modern Punjabi Poetry: from Bhai Vir Singh to Surjit Patar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2016

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 PUNJABI UNIVERSITY, PATIALA © Punjabi University, Patiala (Established under Punjab Act No. 35 of 1961) Editor Dr. Shivani Thakar Asst. Professor (English) Department of Distance Education, Punjabi University, Patiala Laser Type Setting : Kakkar Computer, N.K. Road, Patiala Published by Dr. Manjit Singh Nijjar, Registrar, Punjabi University, Patiala and Printed at Kakkar Computer, Patiala :{Bhtof;Nh X[Bh nk;k wjbk ñ Ò uT[gd/ Ò ftfdnk thukoh sK goT[gekoh Ò iK gzu ok;h sK shoE tk;h Ò ñ Ò x[zxo{ tki? i/ wB[ bkr? Ò sT[ iw[ ejk eo/ w' f;T[ nkr? Ò ñ Ò ojkT[.. nk; fBok;h sT[ ;zfBnk;h Ò iK is[ i'rh sK ekfJnk G'rh Ò ò Ò dfJnk fdrzpo[ d/j phukoh Ò nkfg wo? ntok Bj wkoh Ò ó Ò J/e[ s{ j'fo t/; pj[s/o/.. BkBe[ ikD? u'i B s/o/ Ò ô Ò òõ Ò (;qh r[o{ rqzE ;kfjp, gzBk óôù) English Translation of University Dhuni True learning induces in the mind service of mankind. One subduing the five passions has truly taken abode at holy bathing-spots (1) The mind attuned to the infinite is the true singing of ankle-bells in ritual dances. With this how dare Yama intimidate me in the hereafter ? (Pause 1) One renouncing desire is the true Sanayasi. From continence comes true joy of living in the body (2) One contemplating to subdue the flesh is the truly Compassionate Jain ascetic. Such a one subduing the self, forbears harming others. (3) Thou Lord, art one and Sole. -

Dr Jaswant Singh Neki

The Stalwarts http://doi.org/10.18231/j.tjp.2019.034 Dr Jaswant Singh Neki Madhur Rathi Postgraduate, Dept. of Psychiatry, Institute of Mental Health, Osmania Medical College, Hyderabad, Telangana, India *Corresponding Author: Madhur Rathi Email: [email protected] Abstract Dr. Jaswant Singh Neki (1925–2015) is amongst the foremost psychiatrists of India. He has been variously described as a world-renowned mental health expert, a noted metaphysical poet, a teacher par excellence, and an excellent humane person of international repute. He joined his graduate course in medicine and surgery from King Edward Medical College, Lahore and completed graduation from Medical College, Amritsar.1 He passed his MA (Psychology) from Aligarh Muslim University. Later he passed DPM exam from All India Institute of Mental Health, Bangalore. He held high academic and administrative positions including Consultant - WHO, Geneva and UNDP S-E Asia. Keywords: J S Neki, Guru-Chela relationship, Kairos, Poet, Cross cultural psychotherapy. Introduction worked there for about a decade. Then he was appointed Dr Neki was born in village Murid, Distt. Jhelum (Pakistan), Director of the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education on 27th August, 1925. His father, S. Hari Gulab Singh and and Research, Chandigarh. He spent next three years there. his mother, Smt. Sita Wanti were both God-fearing From there, he was picked up by the World Health individuals.1 When he was an infant, his parents shifted to Organization, Geneva, as a consultant for a project in Quetta (Baluchistan). He joined Khalsa High School in Africa. He served in Africa for over four years (1981- Quetta, from where he matriculated in 1941 securing the 1985)1. -

Gurdial Singh: Messiah of the Marginalized

Gurdial Singh: Messiah of the Marginalized Rana Nayar Panjab University, Chandigarh In the past two months, Indian literature has lost two of its greatest writers; first it was the redoubtable Mahasweta Devi, who left us in July, and then it was the inimitable Gurdial Singh (August 18, 2016). Both these writers enjoyed a distinctive, pre-eminent position in their respective literary traditions, and both managed to transcend the narrow confines of the geographical regions within which they were born, lived or worked. Strangely enough, despite their personal, ideological, aesthetic and/or cultural differences, both worked tirelessly, all their lives, for restoring dignity, pride and self-respect to “the last man” on this earth. What is more, both went on to win the highest literary honor of India, the Jnanpeeth, for their singular contribution to their respective languages, or let me say, to the rich corpus of Indian Literature. Needless to say, the sudden departure of both these literary giants has created such a permanent vacuum in our literary circles that neither time nor circumstance may now be able to replenish it, ever. And it is, indeed, with a very heavy heart and tearful, misty eyes that I bid adieu to both these great writers, and also pray for the eternal peace of their souls. Of course, I could have used this opportunity to go into a comparative assessment of the works of both Mahasweta Devi and Gurdial Singh, too, but I shall abstain from doing so for obvious reasons. The main purpose of this essay, as the title clearly suggests, is to pay tribute to Gurdial Singh's life and work. -

The Sikh Prayer)

Acknowledgements My sincere thanks to: Professor Emeritus Dr. Darshan Singh and Prof Parkash Kaur (Chandigarh), S. Gurvinder Singh Shampura (member S.G.P.C.), Mrs Panninder Kaur Sandhu (nee Pammy Sidhu), Dr Gurnam Singh (p.U. Patiala), S. Bhag Singh Ankhi (Chief Khalsa Diwan, Amritsar), Dr. Gurbachan Singh Bachan, Jathedar Principal Dalbir Singh Sattowal (Ghuman), S. Dilbir Singh and S. Awtar Singh (Sikh Forum, Kolkata), S. Ravinder Singh Khalsa Mohali, Jathedar Jasbinder Singh Dubai (Bhai Lalo Foundation), S. Hardarshan Singh Mejie (H.S.Mejie), S. Jaswant Singh Mann (Former President AISSF), S. Gurinderpal Singh Dhanaula (Miri-Piri Da! & Amritsar Akali Dal), S. Satnam Singh Paonta Sahib and Sarbjit Singh Ghuman (Dal Khalsa), S. Amllljit Singh Dhawan, Dr Kulwinder Singh Bajwa (p.U. Patiala), Khoji Kafir (Canada), Jathedar Amllljit Singh Chandi (Uttrancbal), Jathedar Kamaljit Singh Kundal (Sikh missionary), Jathedar Pritam Singh Matwani (Sikh missionary), Dr Amllljit Kaur Ibben Kalan, Ms Jagmohan Kaur Bassi Pathanan, Ms Gurdeep Kaur Deepi, Ms. Sarbjit Kaur. S. Surjeet Singh Chhadauri (Belgium), S Kulwinder Singh (Spain), S, Nachhatar Singh Bains (Norway), S Bhupinder Singh (Holland), S. Jageer Singh Hamdard (Birmingham), Mrs Balwinder Kaur Chahal (Sourball), S. Gurinder Singh Sacha, S.Arvinder Singh Khalsa and S. Inder Singh Jammu Mayor (ali from south-east London), S.Tejinder Singh Hounslow, S Ravinder Singh Kundra (BBC), S Jameet Singh, S Jawinder Singh, Satchit Singh, Jasbir Singh Ikkolaha and Mohinder Singh (all from Bristol), Pritam Singh 'Lala' Hounslow (all from England). Dr Awatar Singh Sekhon, S. Joginder Singh (Winnipeg, Canada), S. Balkaran Singh, S. Raghbir Singh Samagh, S. Manjit Singh Mangat, S. -

Saffron Cloud

WAY OF THE SAFFRON CLOUD MYSTERY OF THE NAM-JAP TRANSCENDENTAL MEDITATION THE SIKH WAY A PRACTICAL GUIDE TO CONCENTRATION Dr. KULWANT SINGH PUBLISHED AS A SPECIAL EDITION OF GURBANI ISS JAGG MEH CHANAN, TO HONOR 300TH BIRTHDAY OF THE KHALSA, IN 1999. WAY OF THE SAFFRON CLOUD Electronic Version, for Gurbani-CD, authored by Dr. Kulbir Singh Thind, 3724 Hascienda Street, San Mateo, California 94403, USA. The number of this Gurbani- CD, dedicated to the sevice of the Panth, is expected to reach 25,000 by the 300th birthday of the Khalsa, on Baisakhi day of 1999. saffron.doc, MS Window 95, MS Word 97. 18th July 1998, Saturday, First Birthday of Sartaj Singh Khokhar. Way of the Saffron Cloud. This book reveals in detail the mystery of the Name of God. It is a spiritual treatise for the uplift of the humanity and is the practical help-book (Guide) to achieve concentration on the Naam-Jaap (Recitation of His Name) with particular stress on the Sikh-Way of doing it. It will be easy to understand if labeled "Transcendental Meditation the Sikh -Way," though meditation is an entirely different procedure. Main purpose of this book is to train the aspirant from any faith, to acquire the ability to apply his -her own mind independently, to devise the personalized techniques to focus it on the Lord. Information about the Book - Rights of this Book. All rights are reserved by the author Dr. Kulwant Singh Khokhar, 12502 Nightingale Drive, Chester, Virginia 23836, USA. Phone – mostly (804)530-0160, and sometimes (804)530-5117. -

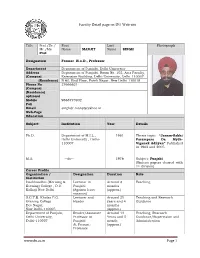

Faculty Detail Page on DU Web-Site

Faculty Detail page on DU Web-site Title Prof./Dr./ First Last Photograph Mr./Ms Name MANJIT Name SINGH Prof. Designation Former H.o.D., Professor Department Department of Punjabi, Delhi University Address Department of Punjabi, Room No. 102, Arts Faculty, (Campus) Extension Building, Delhi University, Delhi-110007 (Residence) B-60, IInd Floor, Fateh Nagar, New Delhi-110018 Phone No 27666621 (Campus) (Residence) optional Mobile 9868773902 Fax Email [email protected] Web-Page Education Subject Institution Year Details Ph.D. Department of M.I.L., 1981 Thesis topic: “Janam-Sakhi Delhi University , Delhi- Parampara Da Myth- 110007 Viganak Adhyan” Published in 1982 and 2005. M.A. --do-- 1976 Subject: Punjabi (Sixteen papers cleared with 1st division) Career Profile Organization / Designation Duration Role Institution Deshbandhu (Morning & Lecturer in Around 2 Teaching Evening) College , D.U. Punjabi months Kalkaji New Delhi (Against leave (approx.) vacancy) S.G.T.B. Khalsa P.G. Lecturer and Around 25 Teaching and Research Evening College Reader years and 4 Guidance Dev Nagar, months New Delhi-110005 (approx.) Department of Punjabi, Reader/Associate Around 13 Teaching, Research Delhi University, Professor in Years and 5 Guidance/Supervision and Delhi-110007 Punjabi month Administration At Present: (approx.) Professor www.du.ac.in Page 1 Research Interests / Specialization Mythology & The Science of Myth and Gurmat Poetry Folkloristics, Cross-disciplinary Semiotics Western Poetics and Culturology, Medieval and Modern Punjabi Literature. Research Supervision A. Supervision of awarded Doctoral Theses ______________________________________________________________________________ S.No. Title of the Thesis Year of Present Name of the Scholar Submission Position 1 “San 1850 ton 1900 tak Di 1995 Approved Ms. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E2580 HON

E2580 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks December 13, 2007 shape of Texas. He has also become popular tion’s schools. These incidents have occurred Dingell VA Medical Center in Detroit. Mr. as a cornerstone for community service. all over the country. While some thought Col- Wheeler’s career is marked by numerous hos- After living in the U.S. for a while, he be- umbine was an aberration, it has become pital administration roles and a dedication to came frustrated with the fact that voter turnout clear that this is a serious and growing prob- our men and women who have served in the in American elections was so low. Because of lem in our country that must be addressed. Armed Forces. this, he hosted a voter registration drive at his It is important to point out that in the late Mr. Wheeler was born in Detroit and moved hotel. To encourage residents to participate, 80’s and early 90’s when overall crime was to Canton, Ohio, when he was a teenager. He he offered a free breakfast for registering. going down, youth and young adult arrest received a BS in business administration from Philippe is extremely active as this year’s rates were increasing. the University of Dayton and an MA in hospital president of the Humble Intercontinental Ro- We must ask ourselves why. What makes a administration from Xavier University in Cin- tary and has been named Rotarian of the Year 14-year old feel so disengaged from society cinnati. Mr. Wheeler began his career as a on occasion. -

Satwant Kaur Bhai Vir Singh

Satwant !(aUll BHAI VIR SINGH Translator Rima!· Kaur """"'~"""'Q~ ....#•" . Bhai Vir Singh Sahitya Sadan Bhai Vir Singh Marg New Delhi-110 001 Page 1 www.sikhbookclub.com Satwant Kaur Bhai Vir Singh Translated by BimalKaur © Bhai Vir Singh Sahitya Sadan, New Delhi New Edition: 2008 Publisher: Bhai Vir Singh Sahitya Sadan BhaiVir Singh Marg New Delhi-11 a 001 Printed at: IVY Prints 29216, Joor Bagh Kotla Mubarakpur New Delhi-11 0003 Price; 60/- Page 2 www.sikhbookclub.com , Foreword The Sikh faith founded by Guru Nanak (1469-1539) has existed barely for five centuries; but this relatively short period has been packed with most colourful and inspiring history. Sikhism, as determined by the number of its adherents, is one of the ten great religions of the world. Its principles of monotheism, egalitarianism and proactive martyrdom for freedom of faith represent major evolutionary steps in the development of religious philosophies. Arnold Toynbee, the great world historian, observed: "Mankind's religious future may be obscure; yet one thing can be foreseen. The living higher religions are going to influence each other more than ever before in the days ofincreasing communication between all parts of the world and all branches of the human race. In this coming religious debate, the Sikh religion, and its scripture, the Adi Granth, will have something of special value to say to the rest of the world." Notwithstanding such glowing appreciation oftheir role, information about the Sikhs'contribution to world culture has been very scantily propagated. Bhai Vir Singh, the modem doyen ofSikh world of letters, took upon himself to provide valuable historical accounts of the Sikh way of life. -

Gurdial Singh: a Storyteller Extraordinaire

229 Rana Nayar: Gurdial Singh Gurdial Singh: A Storyteller Extraordinaire Rana Nayar Panjab University, Chandigarh ________________________________________________________________ This article explores the life, times, and writings of Gurdial Singh, who describes himself as a ‘critical realist.’ Beginning his publications in 1957, he has written nine novels, eight collections of short stories, three plays, two prose works, and nine books for children. This article examines themes such as synthesis of tradition and modernity, concern for the underprivileged, and faith in humankind’s revolutionary spirit that run throughout his writings. ________________________________________________________________ Introduction As I sit down to reflect on the range and quality of Gurdial Singh’s fiction, Plato’s famous dictum inevitably comes to mind. In his Republic, Plato is believed to have stated that he looked upon a carpenter as a far better, a far more superior artist than the poet or the painter.1 For Plato, the carpenter had come to embody the image of a complete artist or rather that of a total man. After all, wasn’t he the one who imbued the formless with a sense of structure and form and infused the rugged material reality with untold creative possibilities? By all counts, Gurdial Singh answers the Platonic description of a complete artist rather well. Born to a carpenter father, who insisted that his young son, too, should step into his shoes, Gurdial Singh chose to become instead a carpenter of words, a sculptor of human forms, and a painter of life in all its hues. On being refused funding by his parents for education beyond high school, he decided to be his own mentor, slowly toiling his way up from an elementary to a high school teacher, from there to a college lecturer, and finally a professor at a Regional Centre of Punjabi University. -

Interfaith Dialogue: a Perspective from Sikhism Abstract Introduction

Abstracts of Sikh Studies, Vol XXII, Issue 4, Oct.-Dec. 2020, Institute of Sikh Studies, Chandigarh, India Interfaith Dialogue: A Perspective from Sikhism Dr. Devinder Pal Singh* Center for Understanding Sikhism, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada [email protected] Abstract Interfaith dialogue is perceived as the best mechanism to build mutual understanding and respect among people of different faiths. Although the Interfaith movement can be traced back to the late 19th century, it gained an unprecedented prominence in the years following 9/11. In Western democracies, interfaith initiatives have been enlisted as part of wider multiculturalist responses to the threat of radicalization. Despite, interfaith dialogue's recent emergence on the world stage, it has been an active component of ancient Indian religious traditions. Sikh Gurus' compositions, and their way of life, reveal that they were among the pioneers of interfaith dialogue in their time. They remained in continuous dialogue with other faiths throughout their lifetimes. For them, the real purpose of the interchange was to uphold the true faith in the Almighty Creator and to make it relevant to contemporary society. With this intent, they approached the fellow Muslims and Hindus and tried hard to rejuvenate the real spirit of their respective religions. Guru Nanak's travels to various religious centers of diverse faiths; his life long association with Bhai Mardana (a Muslim); Guru Arjan Dev's inclusion of the verses of the saint- poets of varied faiths, in Sri Guru Granth Sahib; Guru Hargobind's construction of Mosque for Muslims; and Guru Teg Bahadur's laying down of his life for the cause of Hinduism, are just a few examples of the initiatives taken by the Sikh Gurus in this field. -

Legacy of Bhai Ram Singh the Singh Sabha Movement Sikhs in California Contentsissue IV/2007 Ceditorial 2 the Imperatives of Education JSN

I V / 2 0 0 7 NAGAARA The Khalsa College: Legacy of Bhai Ram Singh The Singh Sabha Movement Sikhs in California ContentsIssue IV/2007 CEditorial 2 The imperatives of education JSN 4 Message of Guru Nanak : Peace and Harmony Onkar Singh 22 Khalsa College Gurdwara Sahib of San Jose A Legacy of Bhai Ram Singh Sikhs in California’s 51 40 Lisa Fernandez / Alan Hess Pervaiz Vandal and Sajida Vandal Central Valley Lea Terhune 34 Flight out of Punjab Ritu Sarin 7 Guru Nanak and his mission Principal Teja Singh 14 The Singh Sabha movement: 57 Bhai Santa Singh : A unique Chalo Amrika! exponent of the Guru’s Hymn Stimulus and Strength 38 45 Californian Sikh personalities By Sardar Harbans Singh C Shamsher Harjap Singh Aujla Editorial Director Editorial Office Printed by Dr Jaswant Singh Neki D-43, Sujan Singh Park Aegean Offset New Delhi 110 003, India F-17, Mayapuri Phase II Executive Editor New Delhi 110 064 Pushpindar Singh Tel: (91-11) 24617234 Fax: (91-11) 24628615 Editorial Board e-mail : [email protected] Please visit us at: Bhayee Sikandar Singh website : www.nishaan.in www.nishaan.in Dr Gurpreet Maini Jyotirmoy Chaudhuri Published by The opinions expressed in Malkiat Singh The Nagaara Trust the articles published in the Inni Kaur (New York) 16-A Palam Marg Nishaan Nagaara do not Cover : The main building of Khalsa College at Amritsar. T. Sher Singh (Toronto) Vasant Vihar necessarily reflect the views or Jag Jot Singh (San Francisco) New Delhi 110 057, India policy of The Nagaara Trust. EEditorialEditorial The imperatives of education t has been said that “Education is that which Diwan that, in 1892, etablished a Khalsa College, and I stays with you after you have forgotten your that too in Amritsar. -

A Complete Guide to Sikhism

A Complete Guide to Sikhism <siqgur pRswid A Complete Guide to Sikhism Dr JAGRAJ SINGH Copyright Dr. Jagraj Singh 1 A Complete Guide to Sikhism < siqgur pRswid[[ “There is only one God, He is infinite, his existence cannot be denied, He is enlightener and gracious” (GGS, p1). “eyk ipqw eyks ky hMm bwrk qUM myrw gurhweI”[[ “He is our common father, we are all His children and he takes care of us all.” --Ibid, p. 611, Guru Nanak Deh shiva bar mohay ihay O, Lord these boons of thee I ask, Shub karman tay kabhoon na taroon I should never shun a righteous task, Na daroon arson jab jae laroon I should be fearless when I go to battle, Nischay kar apni jeet karoon Grant me conviction that victory will be mine with dead certainty, Ar Sikh haun apnay he mann ko As a Sikh may my mind be enshrined with your teachings, Ih laalach haun gun tau uchroon And my highest ambition should be to sing your praises, Jab av kee audh nidhan banay When the hour of reckoning comes At he ran mah tab joojh maroon I should die fighting for a righteous cause in the thick of battlefield. --Chandi Charitar, Guru Gobind Singh Copyright Dr. Jagraj Singh 2 A Complete Guide to Sikhism < siqgur pRswid A COMPLETE GUIDE TO SIKHISM Dr. JAGRAJ SINGH UNISTAR Copyright Dr. Jagraj Singh 3 A Complete Guide to Sikhism A COMPLETE GUIDE TO SIKHISM By Dr. Jagraj Singh Jagraj [email protected] 2011 Published by Unistar Books Pvt. Ltd. S.C.O.26-27, Sector 34A, Chandigarh-160022, India.