Introduction: a Rich and Complex Heritage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sun King Program Notes

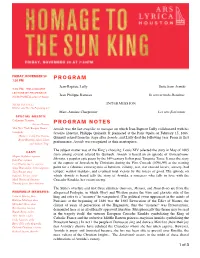

FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 20 PROGRAM 7:30 PM Jean-Baptiste Lully Suite from Armide 7:00 PM: PRE-CONCERT LECTURE BY PROFESSOR Jean-Philippe Rameau In convertendo Dominus JOHN POWELL (UNIV. OF TULSA) wfihe^=e^ii=L= INTERMISSION Hobby Center For The Performing Arts= Marc-Antoine Charpentier Les arts florissants SPECIAL GUESTS: Catherine Turocey, Artistic Director PROGRAM NOTES The New York Barque Dance Company Armide was the last tragédie en musique on which Jean-Baptiste Lully collaborated with his Dancers: Carly Fox Horton, favorite librettist, Philippe Quinault. It premiered at the Paris Opéra on February 15, 1686. Quinault retired from the stage after Armide, and Lully died the following year. From its first Brynt Beitman, Alexis Silver, and Andrew Trego performance, Armide was recognized as their masterpiece. The subject matter was of the King’s choosing: Louis XIV selected the story in May of 1685 CAST: Megan Stapleton, soprano from among several offered by Quinault. Armide is based on an episode of Gerusalemme Julia Fox, soprano liberata, a popular epic poem by the 16th-century Italian poet Torquato Tasso. It uses the story Cecy Duarte, mezzo-soprano of the capture of Jerusalem by Christians during the First Crusade (1096-99) as the starting Sonja Bruzauskas, mezzo-soprano point for a fabulous extravaganza of heroism, villainy, war, star-crossed lovers, sorcery, bad Tony Boutté, tenor temper, warrior maidens, and eventual total victory by the forces of good. The episode on Eduardo Tercero, tenor which Armide is based tells the story of Armida, a sorceress who falls in love with the Mark Diamond, baritone Crusader Rinaldo, her sworn enemy. -

Iphigénie En Tauride

Christoph Willibald Gluck Iphigénie en Tauride CONDUCTOR Tragedy in four acts Patrick Summers Libretto by Nicolas-François Guillard, after a work by Guymond de la Touche, itself based PRODUCTION Stephen Wadsworth on Euripides SET DESIGNER Saturday, February 26, 2011, 1:00–3:25 pm Thomas Lynch COSTUME DESIGNER Martin Pakledinaz LIGHTING DESIGNER Neil Peter Jampolis CHOREOGRAPHER The production of Iphigénie en Tauride was Daniel Pelzig made possible by a generous gift from Mr. and Mrs. Howard Solomon. Additional funding for this production was provided by Bertita and Guillermo L. Martinez and Barbara Augusta Teichert. The revival of this production was made possible by a GENERAL MANAGER gift from Barbara Augusta Teichert. Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine Iphigénie en Tauride is a co-production with Seattle Opera. 2010–11 Season The 17th Metropolitan Opera performance of Christoph Willibald Gluck’s Iphigénie en This performance is being broadcast Tauride live over The Toll Brothers– Metropolitan Conductor Opera Patrick Summers International Radio Network, in order of vocal appearance sponsored by Toll Brothers, Iphigénie America’s luxury Susan Graham homebuilder®, with generous First Priestess long-term Lei Xu* support from Second Priestess The Annenberg Cecelia Hall Foundation, the Vincent A. Stabile Thoas Endowment for Gordon Hawkins Broadcast Media, A Scythian Minister and contributions David Won** from listeners worldwide. Oreste Plácido Domingo This performance is Pylade also being broadcast Clytemnestre Paul Groves** Jacqueline Antaramian live on Metropolitan Opera Radio on Diane Agamemnon SIRIUS channel 78 Julie Boulianne Rob Besserer and XM channel 79. Saturday, February 26, 2011, 1:00–3:25 pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. -

Armide 1778 Gens Van Mechelen Christoyannis Santon Jeffery Watson Martin Wilder

LULLY ARMIDE 1778 GENS VAN MECHELEN CHRISTOYANNIS SANTON JEFFERY WATSON MARTIN WILDER LE CONCERT SPIRITUEL HERVÉ NIQUET SOMMAIRE | CONTENTS | INHALT ARMIDE, D’UN SIÈCLE À L’AUTRE PAR BENOÎT DRATWICKI p. 8 ARMIDE, FROM ONE CENTURY TO THE NEXT BY BENOÎT DRATWICKI p. 14 ARMIDE IM WANDEL DER JAHRHUNDERTE VON BENOÎT DRATWICKI p. 18 SYNOPSIS EN FRANÇAIS p. 28 SYNOPSIS IN ENGLISH p. 32 INHALTSANGABE p. 36 BIOGRAPHIES EN FRANÇAIS p. 40 BIOGRAPHIES IN ENGLISH p. 44 BIOGRAPHIEN p. 46 LIBRETTO p. 50 CRÉDITS, CREDITS, BEZETZUNG p. 77 6 7 LULLY ARMIDE TRAGÉDIE LYRIQUE EN UN PROLOGUE ET CINQ ACTES, CRÉÉE À L’ACADÉMIE ROYALE DE MUSIQUE À PARIS LE 15 FÉVRIER 1686, VERSION RÉVISÉE EN 1778 PAR LOUIS-JOSEPH FRANCŒUR MUSIQUE DE JEAN-BAPTISTE LULLY (1632-1687) ET LOUIS-JOSEPH FRANCŒUR (1738-1804) LIVRET DE PHILIPPE QUINAULT (1635-1688) VÉRONIQUE GENS ARMIDE REINOUD VAN MECHELEN RENAUD TASSIS CHRISTOYANNIS HIDRAOT, LA HAINE CHANTAL SANTON JEFFERY PHÉNICE, LUCINDE KATHERINE WATSON SIDONIE, UNE NAÏADE, UN PLAISIR PHILIPPE-NICOLAS MARTIN ARONTE, ARTÉMIDORE, UBALDE ZACHARY WILDER LE CHEVALIER DANOIS LE CONCERT SPIRITUEL CHŒUR ET ORCHESTRE HERVÉ NIQUET DIRECTION COPRODUCTION CENTRE DE MUSIQUE BAROQUE DE VERSAILLES, LE CONCERT SPIRITUEL PARTITION RÉALISÉE ET ÉDITÉE PAR LE CENTRE DE MUSIQUE BAROQUE DE VERSAILLES (JULIEN DUBRUQUE) LULLY ARMIDE CD1 CD2 ACTE I ACTE III 1 OUVERTURE 5’19 1 « Ah ! si la liberté me doit être ravie » ARMIDE 3’12 2 « Dans un jour de triomphe, au milieu des plaisirs » PHÉNICE, SIDONIE 2’45 2 « Que ne peut point votre art ? La force en est -

LULLY, J.: Armide (Opera Lafayette, 2007) Naxos 8.66020910 Jeanbaptiste Lully (1632 1687) Armide Tragé

LULLY, J.: Armide (Opera Lafayette, 2007) Naxos 8.66020910 JeanBaptiste Lully (1632 1687) Armide Tragédie en musique Libretto by Philippe Quinault, based on Torquato Tasso's La Gerusalemme liberata (Jerusalem Delivered), transcribed and adapted from Le théâtre de Mr Quinault, contenant ses tragédies, comédies et opéras (Paris: Pierre Ribou, 1715), vol. 5, pp. 389428. ACTE I ACT I Le théâtre représente une grande place ornée d’un arc de The scene represents a public place decorated with a Triumphal triomphe Arch. SCÈNE I SCENE I ARMIDE, PHÉNICE, SIDONIE ARMIDE, PHENICE, SIDONIE PHÉNICE PHENICE Dans un jour de triomphe, au milieu des plaisirs, On a day of victory, amid its pleasures, Qui peut vous inspirer une sombre tristesse? Who can inspire such dark sadness in you? La gloire, la grandeur, la beauté, la jeunesse, Glory, greatness, beauty, youth, Tous les biens comblent vos désirs. All these bounties fulfill your desires. SIDONIE SIDONIE Vous allumez une fatale flamme You spark a fatal flame Que vous ne ressentez jamais ; That you never feel: L’amour n’ose troubler la paix Love does not dare trouble the peace Qui règne dans votre âme. That reigns in your soul. ARMIDE, PHÉNICE et SIDONIE ensemble ARMIDE, PHENICE & SIDONIE together Quel sort a plus d’appâts? What fate is more desirable? Et qui peut être heureux si vous ne l’êtes pas? And who can be happy if you are not? PHÉNICE PHENICE Si la guerre aujourd’hui fait craindre ses ravages, If today war threatens its ravages, C’est aux bords du Jourdain qu’ils doivent s’arrêter. -

Passacaille of Armide

The ‘Passacaille of Armide’ Revisited: Rhetorical Aspects of Quinault’s / Lully’s tragédie en musique Kimiko Okamoto The tragédie en musique is a dramatic genre invented by for the effective deliverance of ideas. Oratory can strengthen Philippe Quinault and Jean-Baptiste Lully in the tradition of its impact by elaborating the usage of words, and to this end, French musical theatre; Armide was the last collaboration of techniques of word arrangement were systematised into those creators, and was first staged in 1686. The arch-shaped ‘figures’ and ‘tropes’; the former was absorbed into German (palindromic) symmetry of the verbal, musical and dramatic music theory, and named Figurenlehre. According to the structures of this genre has been pointed out by a number of Figurenlehre, musical motifs are manoeuvred in the same scholars,1 whereas few have discussed its rhetorical order, manner as words in oratory. Although dance treatises never another structural feature of seventeenth and early eight- mention rhetorical figures, the ways steps are arranged in the eenth-century compositions. Judith Schwartz was one of the notated choreographies bear a striking resemblance to these few to analyse the choreography of the ‘Passacaille’ from Act figures. A short sequence of steps often forms a choreo- V of Armide with reference to rhetorical structure.2 Notwith- graphic motif, which functions as a building block of a phrase standing, she applied the theory exclusively to choreogra- through repetition, enlargement, diminution and inversion – phy, leaving the music outside the rhetorical framework, just as the manipulation of words in speech and the manoeu- which Schwartz regarded as ‘asymmetry at odds with the vre of motifs in music. -

NOTES on GLUCK's ARMIDE by CARL VAN VECHTEN ICHARD WAGNER, Like Many Another Great Man, Took

NOTES ON GLUCK'S ARMIDE By CARL VAN VECHTEN ICHARD WAGNER, like many another great man, took what he wanted where he found it. Everyone has heard Downloaded from R the story of his remark to his father-in-law when that august musician first listened to Die WalkHre: "You will recognize this theme, Papa Liszt?" The motto in question occurs when Sieglinde sings: Kehrte der Voder nun heim. Liszt had used the tune at the beginning of his Faust symphony. Not long ago, in http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ playing over Schumann's Kinderscenen, I discovered Brunnhilde's magic slumber music, exactly as it appears in the music drama, in the piece pertinently called Kind im Einschlummern. When Weber's Euryanihe was revived recently at the Metropolitan Opera House it had the appearance of an old friend, although comparatively few in the first night audience had heard the opera before. One recognized tunes, characters, and scenes, because Wagner had found them all good enough to use in Tannh&user at University of Toronto Library on July 15, 2015 and Lohengrin. 'But, at least, you will object, he invented the music drama. That, I am inclined to believe, is just what he did not do, as anyone may see for himself who will take the trouble to glance over the scores of the Chevalier Gluck and to read the preface to Alceste. Gluck's reform of the opera was gradual; Orphie (in its French version), Alceste, and IphigSnie en Aulide, all of which antedate Armide, are replete with indications of what was to come; but Armide, it seems to me, is, in intention at least, almost the music drama, as we use the term to-day. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title A Second Refuge: French Opera and the Huguenot Migration, c. 1680 - c. 1710 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6ck4p872 Author Ahrendt, Rebekah Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California A Second Refuge French Opera and the Huguenot Migration, c. 1680 – c. 1710 By Rebekah Susannah Ahrendt A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kate van Orden, Chair Professor Richard Taruskin Professor Peter Sahlins Fall 2011 A Second Refuge French Opera and the Huguenot Migration, c. 1680 – c. 1710 Copyright 2011 by Rebekah Susannah Ahrendt 1 Abstract A Second Refuge French Opera and the Huguenot Migration, c. 1680 – c. 1710 by Rebekah Susannah Ahrendt Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Kate van Orden, Chair This dissertation examines the brief flowering of French opera on stages outside of France around the turn of the eighteenth century. I attribute the sudden rise and fall of interest in the genre to a large and noisy migration event—the flight of some 200,000 Huguenots from France. Dispersed across Western Europe and beyond, Huguenots maintained extensive networks that encouraged the exchange of ideas and of music. And it was precisely in the great centers of the Second Refuge that French opera was performed. Following the wide-ranging career path of Huguenot impresario, novelist, poet, and spy Jean-Jacques Quesnot de la Chenée, I construct an alternative history of French opera by tracing its circulation and transformation along Huguenot migration routes. -

Positioning Gluck Historically in Early Twentieth-Century France William Gibbons

Document généré le 29 sept. 2021 03:20 Intersections Canadian Journal of Music Revue canadienne de musique --> Voir l’erratum concernant cet article Iphigénie à Paris: Positioning Gluck Historically in Early Twentieth-Century France William Gibbons Volume 27, numéro 1, 2006 Résumé de l'article Dernier des principaux opéras de Gluck à être représenté après une période URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1013158ar d’oubli, Iphigénie en Aulide a été produit à l’Opéra-Comique de Paris en DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1013158ar décembre 1907. La réception critique qui suivit opposa Vincent d’Indy, féroce critique de cette production, et son directeur, Albert Carré. D’Indy répliqua Aller au sommaire du numéro dans les semaines suivantes en dirigeant l’ouverture d’Iphigénie à titre de rectificatif musical de la présentation de l’Opéra-Comique. Cet événement inhabituel met en évidence le problème historiographique posé par Gluck aux Éditeur(s) critiques français du début du XXe siècle : sa musique était-elle orientée vers le passé des tragédies lyriques de Lully et Rameau ou préfigurait-elle les drames Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités musicaux wagnériens du XIXe siècle? La production d’Iphigénie à canadiennes l’Opéra-Comique en 1907 et ses séquelles résume le combat visant à intégrer Gluck dans de nouvelles, et souvent concurrentes, trames de l’histoire de la ISSN musique. 1911-0146 (imprimé) 1918-512X (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Gibbons, W. (2006). Iphigénie à Paris: Positioning Gluck Historically in Early Twentieth-Century France. Intersections, 27(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.7202/1013158ar All Rights Reserved © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. -

Gluck, Iphigénie En Tauride

Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714-1787) Iphigénie en Tauride (Iphigenia in Tauris) Opera in four acts Libretto by Nicolas-François Guillard First performance: Paris, May 18, 1779 Cast: Iphigénie, priestess of Diana ......... soprano Oreste, her brother ......... baritone Pylade, friend of Oreste ......... tenor Thoas, king of Tauris ......... bass First priestess ......... soprano Second priestess ......... soprano A Greek woman ......... soprano A Scythian ......... bass Minister of Thoas ......... bass Diana, the goddess ......... soprano Choruses of priestesses, Scythians, Furies, Greek warriors ***************************** Program note by Martin Pearlman © Martin Pearlman, 2020 Gluck, a composer esteemed by Berlioz and admired by Wagner, whose name is engraved next to Beethoven's and Mozart's on many nineteenth-century concert halls, is sadly neglected today. Histories of music grant Gluck a prominent place as an important mid-eighteenth-century revolutionary, who gave opera a new breath of life, broke down formal conventions to make opera dynamic and truly dramatic, and influenced the course of opera into the nineteenth century. Rousseau spoke for many when he described Gluck's operas as the beginning of a new era, and audiences of the time found the operas unprecedented in their dramatic impact. Yet today, his best known opera, Orfeo ed Euridice, is heard only occasionally, and his later works-- including Iphigénie en Tauride, which is widely considered his greatest achievement- - are rarely performed. The music itself, considered apart from the drama, is very attractive, but relatively simple. Heard in its dramatic context, though, we feel Gluck's real genius. He was first and foremost a dramatist, aiming everything in the music toward characterization and powerful dramatic effects. -

The World of Lully

Cedille Records CDR 90000 043 The World of Lully Music of Jean-Baptiste Lully and his Followers CHICAGO BAROQUE ENSEMBLE WITH PATRICE MICHAELS BEDI, SOPRANO DDD Absolutely Digital CDR 90000 043 THE WORLD OF JEAN-BAPTISTE LULLY (1632-1687) Lully: Première Divertissement (15:09) 1 Ouverture from Armide (2:29) 2 Air from Persée (1:18) 3 Serenade from Ballet des plaisirs (4:31) 4 Air from Phaeton (0:50) 5 Chanson contre les jaloux from Ballet de l’amour Malade (2:23) 6 Minuet from Armide (0:44) 7 Air: Pauvres amants from Le Sicilen (2:48) Jean-Féry Rebel: Le Tombeau de Monsieur Lully (14:01) 8 Lentement (2:39) 9 Vif (2:03) 10 Lentement (2:43) 11 Vivement (3:50) 12 Les Regrets (2:46) Lully: Seconde Divertissement (9:34) 13 Menuet from Alceste (0:58) 14 C’est la saison d’aimer from Alceste (1:32) 15 Recit: Suivons de si douces loix from Ballet d’Alcidiane (1:48) 16 Gavotte from Amadis (1:16) 17 Gigue – Les Plaisirs nous suivent from Amadis (3:56) Lully, arr. Jean d’Anglebert: Pièces de clavecin (7:35) 18 Ouverture de la Mascarade (3:53) 19 Les songes agréables (1:54) 20 Gigue (1:44) 21 Lully: Plainte de Cloris from Le Grand Divertissement Royal de Versailles (5:26) 22 Lully: Galliarde from Trios pour le coucher du roi (3:07) 23 Marin Marais: Tombeau de Lully from Second livre de pièces de violes (6:21) Lully: Armide, Tragedie lyrique (selections) (15:50) 24 Recit: Enfin il est en ma puissance (3:18) 25 Air: Venez, venez seconder mes desirs (1:10) 26 Air (0:53) 27 Passacaille (arr. -

Armida Di Giacomo Durazzo: Modernità Di Un Dramma “Fatto Italiano” Verso La Riforma Teatrale Di Metà Settecento

Armida di Giacomo Durazzo: modernità di un dramma “fatto italiano” verso la riforma teatrale di metà settecento Andrea Lanzola La stesura di Armida da parte del Generalspektakeldirektor di Vienna Giacomo Durazzo1 e la sua messa in scena prendono le mosse da una circostanza di carattere storico - politico: le nozze di Giuseppe II, figlio ed erede al trono di Maria Teresa d’Austria, con Isabella di Borbone Parma, nipote di Luigi XV di Francia. Le rispettive patrie dei fidanzati organizzarono solenni festeggiamenti, con la produzione di nuovi spettacoli, feste teatrali e melodrammi. Per la partenza dell’Infanta da Parma, Carlo Innocenzo Frugoni e Tommaso Traetta realizzarono in collaborazione Le feste d’Imeneo in un prologo e tre atti d' impronta francese. Durazzo, in qualità di Cavagliere di musica della capitale austriaca fu impegnato fin dall’estate del 1760 nei preparativi per le nozze, che dovevano svolgersi nell’ottobre di quello stesso anno. A Metastasio era stato affidato già molti mesi prima2 il compito di produrre una nuova festa teatrale, Alcide al bivio, che, come l’epistolario ci documenta3, ebbe una stesura piuttosto tormentata, costringendo la non più fertile vena del poeta cesareo ad un notevole sforzo. Tale circostanza ci è dimostrata anche dal fatto che Durazzo dovette rivolgersi, per le altre composizioni letterarie occorrenti, a Giannambrogio Migliavacca4, allievo del poeta cesareo. 1 Giacomo Durazzo (1717 - 1794). Figlio di Giovan Luca e di Paola Franzone, ricevette un’eccellente educazione; fin da giovanissimo dimostrò inclinazione per la musica e la recitazione, frequentando assiduamente il Teatro Falcone di Genova, appartenente alla sua famiglia. Incaricato di curare i rapporti diplomatici relativi alla pace di Acquisgrana (1748), fu inviato a Vienna e, apprezzatone l’ambiente culturale e politico, la prescelse come propria patria. -

Antonio Salieri Armida Lenneke Ruiten · Florie Valiquette · Teresa Iervolino · Ashley Riches Chœur De Chambre De Namur Les Talens Lyriques Christophe Rousset

1 2 ANTONIO SALIERI ARMIDA LENNEKE RUITEN · FLORIE VALIQUETTE · TERESA IERVOLINO · ASHLEY RICHES CHŒUR DE CHAMBRE DE NAMUR LES TALENS LYRIQUES CHRISTOPHE ROUSSET 3 Enregistré par Little Tribeca du 10 au 13 juillet 2020 à la Philharmonie de Paris Cet enregistrement a été réalisé avec le généreux soutien de Madame Aline Foriel-Destezet. Direction artistique, prise de son : Nicolas Bartholomée et Franck Jaffrès assistés de Hugo Scremin Montage, mixage et mastering : Franck Jaffrès Enregistré en 24-bit/96kHZ English translation by Mary Pardoe · Übersetzungen ins Deutsche: Hilla Maria Heintz Traduzione italiana a cura di Francesca Martino · Traduction française par Laurent Cantagrel et Simone Casaldi Édition musicale réalisée par Nicolas Sceaux pour Les Talens Lyriques. Coach italien : Rita de Letteriis Les Talens Lyriques sont soutenus par le ministère de la Culture-DRAC Île-de-France, la Ville de Paris et le Cercle des Mécènes. L’ensemble remercie ses Grands Mécènes : la Fondation Annenberg / GRoW – Gregory et Regina Annenberg Weingarten, Madame Aline Foriel-Destezet et Mécénat Musical Société Générale. Les Talens Lyriques sont depuis 2011 artistes associés, en résidence à la Fondation Singer-Polignac. [LC] 83780 · AP244 ℗ 2021 Little Tribeca · Les Talens Lyriques © 2021 Little Tribeca · Les Talens Lyriques 1 rue Paul Bert, 93500 Pantin apartemusic.com lestalenslyriques.com 4 ARMIDA Dramma per musica in three acts by Antonio Salieri (1750-1825) On a libretto by Marco Coltellini (1724-1777) First performed at the Burgtheater in Vienna, on 2 June 1771 WORLD PREMIERE RECORDING 5 6 ATTO PRIMO 1. Sinfonia 5’10 2. Scena 1. Coro: Sparso di pure brine 2’57 3.