Passacaille of Armide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keyboard Arrangements of Music by Jean-Baptiste Lully: Introduction

Keyboard Arrangements of Music by Jean-Baptiste Lully, ed. David Chung, 2014 Introduction, p. i Abbreviations Bonfils 1974 Bonfils, Jean, ed. Livre d’orgue attribué à J.N. Geoffroy, Le Pupitre: no. 53. Paris: Heugel, 1974. Chung 1997 Chung, David. “Keyboard Arrangements and Their Significance for French Harpsichord Music.” 2 vols. PhD diss., University of Cambridge, 1997. Chung 2004 Chung, David, ed. Jean-Baptiste Lully: 27 brani d’opera transcritti per tastiera nei secc. XVII e XVIII. Bologna: UT Orpheus Edizioni, 2004. Gilbert 1975 Gilbert, Kenneth, ed. Jean-Henry d’Anglebert, Pièces de clavecin, Le Pupitre: no. 54. Paris: Heugel, 1975. Gustafson 1979 Gustafson, Bruce. French Harpsichord Music of the 17th Century: A Thematic Catalog of the Sources with Commentary. 3 vols. Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1979. Gustafson 2007 Gustafson, Bruce. Chambonnières: A Thematic Catalogue—The Complete Works of Jacques Champion de Chambonnières (1601/02–72), JSCM Instrumenta 1, 2007, r/2011. (http://sscm- jscm.org/instrumenta_01). Gustafson-Fuller 1990 Gustafson, Bruce and David Fuller. A Catalogue of French Harpsichord Music 1699-1780. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990. Harris 2009 Harris, C. David, ed. Jean Henry D’Anglebert: The Collected Works. New York: The Broude Trust, 2009. Howell 1963 Howell, Almonte Charles Jr., ed. Nine Seventeenth-Century Organ Transcriptions from the Operas of Lully. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1963. LWV Schneider, Herbert. Chronologisch-Thematisches Verzeichnis sämtlicher Werke von Jean-Baptiste Lully. Tutzing: Hans Schneider, 1981. WEB LIBRARY OF SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY MUSIC (www.sscm-wlscm.org) Monuments of Seventeenth-Century Music Vol. 1 Keyboard Arrangements of Music by Jean-Baptiste Lully, ed. -

103 the Music Library of the Warsaw Theatre in The

A. ŻÓRAWSKA-WITKOWSKA, MUSIC LIBRARY OF THE WARSAW..., ARMUD6 47/1-2 (2016) 103-116 103 THE MUSIC LIBRARY OF THE WARSAW THEATRE IN THE YEARS 1788 AND 1797: AN EXPRESSION OF THE MIGRATION OF EUROPEAN REPERTOIRE ALINA ŻÓRAWSKA-WITKOWSKA UDK / UDC: 78.089.62”17”WARSAW University of Warsaw, Institute of Musicology, Izvorni znanstveni rad / Research Paper ul. Krakowskie Przedmieście 32, Primljeno / Received: 31. 8. 2016. 00-325 WARSAW, Poland Prihvaćeno / Accepted: 29. 9. 2016. Abstract In the Polish–Lithuanian Common- number of works is impressive: it included 245 wealth’s fi rst public theatre, operating in War- staged Italian, French, German, and Polish saw during the reign of Stanislaus Augustus operas and a further 61 operas listed in the cata- Poniatowski, numerous stage works were logues, as well as 106 documented ballets and perform ed in the years 1765-1767 and 1774-1794: another 47 catalogued ones. Amongst operas, Italian, French, German, and Polish operas as Italian ones were most popular with 102 docu- well ballets, while public concerts, organised at mented and 20 archived titles (totalling 122 the Warsaw theatre from the mid-1770s, featured works), followed by Polish (including transla- dozens of instrumental works including sym- tions of foreign works) with 58 and 1 titles phonies, overtures, concertos, variations as well respectively; French with 44 and 34 (totalling 78 as vocal-instrumental works - oratorios, opera compositions), and German operas with 41 and arias and ensembles, cantatas, and so forth. The 6 works, respectively. author analyses the manuscript catalogues of those scores (sheet music did not survive) held Keywords: music library, Warsaw, 18th at the Archiwum Główne Akt Dawnych in War- century, Stanislaus Augustus Poniatowski, saw (Pl-Wagad), in the Archive of Prince Joseph musical repertoire, musical theatre, music mi- Poniatowski and Maria Teresa Tyszkiewicz- gration Poniatowska. -

Parte Il Celeberrimo ‘A Solo’ «Le Perfide Renaud Me Fuit»

La Scena e l’Ombra 13 Collana diretta da Paola Cosentino Comitato scientifico: Alberto Beniscelli Bianca Concolino Silvia Contarini Giuseppe Crimi Teresa Megale Lisa Sampson Elisabetta Selmi Stefano Verdino DOMENICO CHIODO ARMIDA DA TASSO A ROSSINI VECCHIARELLI EDITORE Pubblicato con il contributo dell’Università di Torino Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici © Vecchiarelli Editore S.r.l. – 2018 Piazza dell’Olmo, 27 00066 Manziana (Roma) Tel. e fax 06.99674591 [email protected] www.vecchiarellieditore.com ISBN 978-88-8247-419-5 Indice Armida nella Gerusalemme liberata 7 Le prime riscritture secentesche 25 La seconda metà del secolo 59 Il paradosso haendeliano e le Armide rococò 91 Ritorno a Parigi (passando per Vienna) 111 Ritorno a Napoli 123 La magia è il teatro 135 Bibliografia 145 Indice dei nomi 151 ARMIDA NELLA GERUSALEMME LIBERATA Per decenni, ma forse ancora oggi, tra i libri di testo in uso nella scuola secondaria per l’insegnamento letterario ha fatto la parte del leone il manuale intitolato Il materiale e l’immaginario: se lo si consulta alle pa- gine dedicate alla Gerusalemme liberata si può leggere che del poema «l’argomento è la conquista di Gerusalemme da parte dei crociati nel 1099» e che «Tasso scelse un argomento con caratteri non eruditi ma di attualità e a forte carica ideologica. Lo scontro fra l’Occidente cri- stiano e l’Islam - il tema della crociata - si rinnovava infatti per la mi- naccia dell’espansionismo turco in Europa e nel Mediterraneo». Tale immagine del poema consegnata alle attuali generazioni può conser- varsi soltanto a patto, come di fatto è, che non ne sia proprio prevista la lettura e viene da chiedersi che cosa avrebbero pensato di tali af- fermazioni gli europei dei secoli XVII e XVIII, ovvero dei secoli in cui la Liberata era lettura immancabile per qualunque europeo mediamen- te colto. -

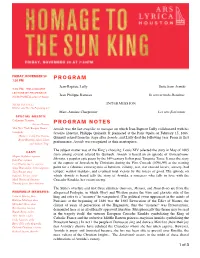

Sun King Program Notes

FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 20 PROGRAM 7:30 PM Jean-Baptiste Lully Suite from Armide 7:00 PM: PRE-CONCERT LECTURE BY PROFESSOR Jean-Philippe Rameau In convertendo Dominus JOHN POWELL (UNIV. OF TULSA) wfihe^=e^ii=L= INTERMISSION Hobby Center For The Performing Arts= Marc-Antoine Charpentier Les arts florissants SPECIAL GUESTS: Catherine Turocey, Artistic Director PROGRAM NOTES The New York Barque Dance Company Armide was the last tragédie en musique on which Jean-Baptiste Lully collaborated with his Dancers: Carly Fox Horton, favorite librettist, Philippe Quinault. It premiered at the Paris Opéra on February 15, 1686. Quinault retired from the stage after Armide, and Lully died the following year. From its first Brynt Beitman, Alexis Silver, and Andrew Trego performance, Armide was recognized as their masterpiece. The subject matter was of the King’s choosing: Louis XIV selected the story in May of 1685 CAST: Megan Stapleton, soprano from among several offered by Quinault. Armide is based on an episode of Gerusalemme Julia Fox, soprano liberata, a popular epic poem by the 16th-century Italian poet Torquato Tasso. It uses the story Cecy Duarte, mezzo-soprano of the capture of Jerusalem by Christians during the First Crusade (1096-99) as the starting Sonja Bruzauskas, mezzo-soprano point for a fabulous extravaganza of heroism, villainy, war, star-crossed lovers, sorcery, bad Tony Boutté, tenor temper, warrior maidens, and eventual total victory by the forces of good. The episode on Eduardo Tercero, tenor which Armide is based tells the story of Armida, a sorceress who falls in love with the Mark Diamond, baritone Crusader Rinaldo, her sworn enemy. -

Introduction: a Rich and Complex Heritage

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01237-0 - Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart Ralph P. Locke Excerpt More information part i Introduction: a rich and complex heritage © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01237-0 - Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart Ralph P. Locke Excerpt More information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01237-0 - Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart Ralph P. Locke Excerpt More information 1 Images and principles Images of Otherness This book tells two intertwined stories that have long needed to be told. It tells how Western music, during the years 1500–1800, reflected, reinforced, and sometimes challenged prevailing conceptions of unfamiliar lands – various Elsewheres – and their peoples. And it also tells how ideas about those locales and peoples contributed to the range and scope of musical works and musical life in the West (that is, in Europe and – to a lesser extent – its overseas colonies). For the most part, the book explores the ways in which those places and peoples were reflected in what we today consider musical works, ranging from operas and dramatic oratorios to foreign-derived instrumental dances such as a sarabande for lute or guitar. But it also explores other cultural products that – though not “musical works”–included a significant musical component: products as different as elaborate courtly ballets and cheaply printed -

The Use of the Polish Folk Music Elements and the Fantasy Elements in the Polish Fantasy on Original Themes In

THE USE OF THE POLISH FOLK MUSIC ELEMENTS AND THE FANTASY ELEMENTS IN THE POLISH FANTASY ON ORIGINAL THEMES IN G-SHARP MINOR FOR PIANO AND ORCHESTRA OPUS 19 BY IGNACY JAN PADEREWSKI Yun Jung Choi, B.A., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Adam Wodnicki, Major Professor Jeffrey Snider, Minor Professor Joseph Banowetz, Committee Member Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Choi, Yun Jung, The Use of the Polish Folk Music Elements and the Fantasy Elements in the Polish Fantasy on Original Themes in G-sharp Minor for Piano and Orchestra, Opus 19 by Ignacy Jan Paderewski. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2007, 105 pp., 5 tables, 65 examples, references, 97 titles. The primary purpose of this study is to address performance issues in the Polish Fantasy, Op. 19, by examining characteristics of Polish folk dances and how they are incorporated in this unique work by Paderewski. The study includes a comprehensive history of the fantasy in order to understand how Paderewski used various codified generic aspects of the solo piano fantasy, as well as those of the one-movement concerto introduced by nineteenth-century composers such as Weber and Liszt. Given that the Polish Fantasy, Op. 19, as well as most of Paderewski’s compositions, have been performed more frequently in the last twenty years, an analysis of the combination of the three characteristic aspects of the Polish Fantasy, Op.19 - Polish folk music, the generic rhetoric of a fantasy and the one- movement concerto - would aid scholars and performers alike in better understanding the composition’s engagement with various traditions and how best to make decisions about those traditions when approaching the work in a concert setting. -

Iphigénie En Tauride

Christoph Willibald Gluck Iphigénie en Tauride CONDUCTOR Tragedy in four acts Patrick Summers Libretto by Nicolas-François Guillard, after a work by Guymond de la Touche, itself based PRODUCTION Stephen Wadsworth on Euripides SET DESIGNER Saturday, February 26, 2011, 1:00–3:25 pm Thomas Lynch COSTUME DESIGNER Martin Pakledinaz LIGHTING DESIGNER Neil Peter Jampolis CHOREOGRAPHER The production of Iphigénie en Tauride was Daniel Pelzig made possible by a generous gift from Mr. and Mrs. Howard Solomon. Additional funding for this production was provided by Bertita and Guillermo L. Martinez and Barbara Augusta Teichert. The revival of this production was made possible by a GENERAL MANAGER gift from Barbara Augusta Teichert. Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine Iphigénie en Tauride is a co-production with Seattle Opera. 2010–11 Season The 17th Metropolitan Opera performance of Christoph Willibald Gluck’s Iphigénie en This performance is being broadcast Tauride live over The Toll Brothers– Metropolitan Conductor Opera Patrick Summers International Radio Network, in order of vocal appearance sponsored by Toll Brothers, Iphigénie America’s luxury Susan Graham homebuilder®, with generous First Priestess long-term Lei Xu* support from Second Priestess The Annenberg Cecelia Hall Foundation, the Vincent A. Stabile Thoas Endowment for Gordon Hawkins Broadcast Media, A Scythian Minister and contributions David Won** from listeners worldwide. Oreste Plácido Domingo This performance is Pylade also being broadcast Clytemnestre Paul Groves** Jacqueline Antaramian live on Metropolitan Opera Radio on Diane Agamemnon SIRIUS channel 78 Julie Boulianne Rob Besserer and XM channel 79. Saturday, February 26, 2011, 1:00–3:25 pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Gustav Mahler, Alfred Roller, and the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk: Tristan and Affinities Between the Arts at the Vienna Court Opera Stephen Carlton Thursby Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC GUSTAV MAHLER, ALFRED ROLLER, AND THE WAGNERIAN GESAMTKUNSTWERK: TRISTAN AND AFFINITIES BETWEEN THE ARTS AT THE VIENNA COURT OPERA By STEPHEN CARLTON THURSBY A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2009 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Stephen Carlton Thursby defended on April 3, 2009. _______________________________ Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Dissertation _______________________________ Lauren Weingarden Outside Committee Member _______________________________ Douglass Seaton Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________ Douglass Seaton, Chair, Musicology ___________________________________ Don Gibson, Dean, College of Music The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To my wonderful wife Joanna, for whose patience and love I am eternally grateful. In memory of my grandfather, James C. Thursby (1926-2008). iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the generous assistance and support of numerous people. My thanks go to the staff of the Austrian Theater Museum and Austrian National Library-Music Division, especially to Dr. Vana Greisenegger, curator of the visual materials in the Alfred Roller Archive of the Austrian Theater Museum. I would also like to thank the musicology faculty of the Florida State University College of Music for awarding me the Curtis Mayes Scholar Award, which funded my dissertation research in Vienna over two consecutive summers (2007- 2008). -

Armide 1778 Gens Van Mechelen Christoyannis Santon Jeffery Watson Martin Wilder

LULLY ARMIDE 1778 GENS VAN MECHELEN CHRISTOYANNIS SANTON JEFFERY WATSON MARTIN WILDER LE CONCERT SPIRITUEL HERVÉ NIQUET SOMMAIRE | CONTENTS | INHALT ARMIDE, D’UN SIÈCLE À L’AUTRE PAR BENOÎT DRATWICKI p. 8 ARMIDE, FROM ONE CENTURY TO THE NEXT BY BENOÎT DRATWICKI p. 14 ARMIDE IM WANDEL DER JAHRHUNDERTE VON BENOÎT DRATWICKI p. 18 SYNOPSIS EN FRANÇAIS p. 28 SYNOPSIS IN ENGLISH p. 32 INHALTSANGABE p. 36 BIOGRAPHIES EN FRANÇAIS p. 40 BIOGRAPHIES IN ENGLISH p. 44 BIOGRAPHIEN p. 46 LIBRETTO p. 50 CRÉDITS, CREDITS, BEZETZUNG p. 77 6 7 LULLY ARMIDE TRAGÉDIE LYRIQUE EN UN PROLOGUE ET CINQ ACTES, CRÉÉE À L’ACADÉMIE ROYALE DE MUSIQUE À PARIS LE 15 FÉVRIER 1686, VERSION RÉVISÉE EN 1778 PAR LOUIS-JOSEPH FRANCŒUR MUSIQUE DE JEAN-BAPTISTE LULLY (1632-1687) ET LOUIS-JOSEPH FRANCŒUR (1738-1804) LIVRET DE PHILIPPE QUINAULT (1635-1688) VÉRONIQUE GENS ARMIDE REINOUD VAN MECHELEN RENAUD TASSIS CHRISTOYANNIS HIDRAOT, LA HAINE CHANTAL SANTON JEFFERY PHÉNICE, LUCINDE KATHERINE WATSON SIDONIE, UNE NAÏADE, UN PLAISIR PHILIPPE-NICOLAS MARTIN ARONTE, ARTÉMIDORE, UBALDE ZACHARY WILDER LE CHEVALIER DANOIS LE CONCERT SPIRITUEL CHŒUR ET ORCHESTRE HERVÉ NIQUET DIRECTION COPRODUCTION CENTRE DE MUSIQUE BAROQUE DE VERSAILLES, LE CONCERT SPIRITUEL PARTITION RÉALISÉE ET ÉDITÉE PAR LE CENTRE DE MUSIQUE BAROQUE DE VERSAILLES (JULIEN DUBRUQUE) LULLY ARMIDE CD1 CD2 ACTE I ACTE III 1 OUVERTURE 5’19 1 « Ah ! si la liberté me doit être ravie » ARMIDE 3’12 2 « Dans un jour de triomphe, au milieu des plaisirs » PHÉNICE, SIDONIE 2’45 2 « Que ne peut point votre art ? La force en est -

L'age D'or of the Chamber Wind Ensemble

L’Age d’or of the Chamber Wind Ensemble A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Ensembles and Conducting Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2013 by Danielle D. Gaudry BM, McGill University, 2000 BE, University of Toronto, 2001 MM, The Pennsylvania State University, 2009 Committee Chair: Terence Milligan, DMA ABSTRACT This document presents a narrative history of the chamber wind ensembles led by Paul Taffanel, Georges Barrère and Georges Longy in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Using different historical approaches, this study examines contemporaneous musical society and the chamber wind ensemble genre to explore the context and setting for the genesis of the Société de musique de chambre pour instruments à vents, the Société moderne des instruments à vents, the Longy Club and the Barrère Ensemble of Wind Instruments. A summary of each ensemble leader’s life and description of the activities of the ensemble, selected repertoire and press reactions towards their performances provide essential insights on each ensemble. In demonstrating their shared origins, ideologies, and similarities in programming philosophies, this document reveals why these chamber wind ensembles created a musical movement, a golden age or age d’or of wind chamber music, affecting the local music scene and continuing to hold influence on today’s performers of wind music. ""!! ! Copyright 2013, Danielle D. Gaudry """! ! ! ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to all those who have been a part of my journey, both in the completion of this document and over the course of this degree. -

Classical Mythology in the Victorian Popular Theatre Edith Hall

Pre-print of Hall, E. in International Journal of the Classical Tradition, (1998). Classical Mythology in the Victorian Popular Theatre Edith Hall Introduction: Classics and Class Several important books published over the last few decades have illuminated the diversity of ways in which educated nineteenth-century Britons used ancient Greece and Rome in their art, architecture, philosophy, political theory, poetry, and fiction. The picture has been augmented by Christopher Stray’s study of the history of classical education in Britain, in which he systematically demonstrates that however diverse the elite’s responses to the Greeks and Romans during this period, knowledge of the classical languages served to create and maintain class divisions and effectively to exclude women and working-class men from access to the professions and the upper levels of the civil service. This opens up the question of the extent to which people with little or no education in the classical languages knew about the cultures of ancient Greece and Rome. One of the most important aspects of the burlesques of Greek drama to which the argument turned towards the end of the previous chapter is their evidential value in terms of the access to classical culture available in the mid-nineteenth century to working- and lower- middle-class people, of both sexes, who had little or no formal training in Latin or Greek. For the burlesque theatre offered an exciting medium through which Londoners—and the large proportion of the audiences at London theatres who travelled in from the provinces—could appreciate classical material. Burlesque was a distinctive theatrical genre which provided entertaining semi-musical travesties of well-known texts and stories, from Greek tragedy and Ovid to Shakespeare and the Arabian Nights, between approximately the 1830s and the 1870s. -

"Mixed Taste," Cosmopolitanism, and Intertextuality in Georg Philipp

“MIXED TASTE,” COSMOPOLITANISM, AND INTERTEXTUALITY IN GEORG PHILIPP TELEMANN’S OPERA ORPHEUS Robert A. Rue A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2017 Committee: Arne Spohr, Advisor Mary Natvig Gregory Decker © 2017 Robert A. Rue All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Arne Spohr, Advisor Musicologists have been debating the concept of European national music styles in the Baroque period for nearly 300 years. But what precisely constitutes these so-called French, Italian, and German “tastes”? Furthermore, how do contemporary sources confront this issue and how do they delineate these musical constructs? In his Music for a Mixed Taste (2008), Steven Zohn achieves success in identifying musical tastes in some of Georg Phillip Telemann’s instrumental music. However, instrumental music comprises only a portion of Telemann’s musical output. My thesis follows Zohn’s work by identifying these same national styles in opera: namely, Telemann’s Orpheus (Hamburg, 1726), in which the composer sets French, Italian, and German texts to music. I argue that though identifying the interrelation between elements of musical style and the use of specific languages, we will have a better understanding of what Telemann and his contemporaries thought of as national tastes. I will begin my examination by identifying some of the issues surrounding a selection of contemporary treatises, in order explicate the problems and benefits of their use. These sources include Johann Joachim Quantz’s Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte zu spielen (1752), two of Telemann’s autobiographies (1718 and 1740), and Johann Adolf Scheibe’s Critischer Musikus (1737).