Keyboard Arrangements of Music by Jean-Baptiste Lully: Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Le Journal Intime D'hercule D'andré Dubois La Chartre. Typologie Et Réception Contemporaine Du Mythe D'hercule

Commission de Programme en langues et lettres françaises et romanes Le Journal intime d’Hercule d’André Dubois La Chartre. Typologie et réception contemporaine du mythe d’Hercule Alice GILSOUL Mémoire présenté pour l’obtention du grade de Master en langues et lettres françaises et romanes, sous la direction de Mme. Erica DURANTE et de M. Paul-Augustin DEPROOST Louvain-la-Neuve Juin 2017 2 Le Journal intime d’Hercule d’André Dubois La Chartre. Typologie et réception contemporaine du mythe d’Hercule 3 « Les mythes […] attendent que nous les incarnions. Qu’un seul homme au monde réponde à leur appel, Et ils nous offrent leur sève intacte » (Albert Camus, L’Eté). 4 Remerciements Je tiens à remercier Madame la Professeure Erica Durante et Monsieur le Professeur Paul-Augustin Deproost d’avoir accepté de diriger ce travail. Je remercie Madame Erica Durante qui, par son écoute, son exigence, ses précieux conseils et ses remarques m’a accompagnée et guidée tout au long de l’élaboration de ce présent mémoire. Mais je me dois surtout de la remercier pour la grande disponibilité dont elle a fait preuve lors de la rédaction de ce travail, prête à m’aiguiller et à m’écouter entre deux taxis à New-York. Je remercie également Monsieur Paul-Augustin Deproost pour ses conseils pertinents et ses suggestions qui ont aidé à l’amélioration de ce travail. Je le remercie aussi pour les premières adresses bibliographiques qu’il m’a fournies et qui ont servi d’amorce à ma recherche. Mes remerciements s’adressent également à mes anciens professeurs, Monsieur Yves Marchal et Madame Marie-Christine Rombaux, pour leurs relectures minutieuses et leurs corrections orthographiques. -

Thanks Are Due Sainte Colombe – the Soundtrack from “Tous Les Matins De Monde” Has Some Wonderful Examples to Danny, Tommie, Belinda, of Sainte Colombe’S Music

directed by Jennifer Eriksson In 2007, ABC Classic FM initiated the Lute Project ABC Classics. Daniel has performed and recorded and commissioned four Australian composers with “The Marais Project” on several occasions. to write for him. Tommie Andersson appears on more than 35 CDs and lectures in Lute at Jennifer Eriksson completed her initial musical the Sydney Conservatorium of Music. He is a studies at the Sydney Conservatorium of founding member of The Marais Project. Music. She subsequently studied the viola da gamba with Jaap ter Linden at the Rotterdam Daniel Yeadon has a worldwide career as a cellist Conservatorium where she completed post- and viola da gamba player; his repertoire ranges graduate studies in baroque music. She founded from renaissance to contemporary. His regular The Marais Project in 2000 and also directs 3.00pm Sunday 23rd October 2011 | Recital Hall East, Sydney Conservatorium of Music chamber music collaborators in Australia include the Musica Viva in Schools ensemble, Sounds Daniel Yeadon & Jennifer Eriksson – viola da gamba | Tommie Andersson – theorbo Neal Peres Da Costa, Genevieve Lacey, Ironwood, Baroque. Jennifer is widely recognised as one ”The Marin-ettes“ featuring Belinda Montgomery, Narelle Evans & Mara Kiek – voice Romanza, Kammer, Elision and The Collective. of Australia’s best known and most versatile He has appeared as soloist with the Australian viola da gambists having released several CDs Brandenburg Orchestra, tours frequently with the and recorded frequently for the ABC. She has He was travelling without his renowned 17th century French Australian Chamber Orchestra, plays every year also commissioned numerous new Australian Welcome from viol and borrowing instruments maker. -

This Paper Is a Revised Version of My Article 'Towards A

1 This paper is a revised version of my article ‘Towards a more consistent and more historical view of Bach’s Violoncello’, published in Chelys Vol. 32 (2004), p. 49. N.B. at the end of this document readers can download the music examples. Towar ds a different, possibly more historical view of Bach’s Violoncello Was Bach's Violoncello a small CGda Violoncello “played like a violin” (as Bach’s Weimar collegue Johann Gottfried Walther 1708 stated)? Lambert Smit N.B. In this paper 18 th century terms are in italics. Introduction Bias and acquired preferences sometimes cloud people’s views. Modern musicians’ fondness of their own instruments sometimes obstructs a clear view of the history of each single instrument. Some instrumentalists want to defend the territory of their own instrument or to enlarge 1 it. However, in the 18 th century specialization in one instrument, as is the custom today, was unknown. 2 Names of instruments in modern ‘Urtext’ editions can be misleading: in the Neue Bach Ausgabe the due Fiauti d’ Echo in Bach’s score of Concerto 4 .to (BWV 1049) are interpreted as ‘Flauto dolce’ (=recorder, Blockflöte, flûte à bec), whereas a Fiauto d’ Echo was actually a kind of double recorder, consisting of two recorders, one loud and one soft. (see internet and Bachs Orchestermusik by S. Rampe & D. Sackmann, p. 279280). 1 The bassoon specialist Konrad Brandt, however, argues against the habit of introducing a bassoon in every movement in Bach’s church music where oboes are played (the theory ‘wo Oboen, da auch Fagott’) BachJahrbuch '68. -

Marin Marais

Florence Bolton MARIN MARAIS PIÈCES DE VIOLE la rêveuse Florence Bolton, basse de viole - Benjamin Perrot, théorbe & guitare baroque Carsten Lohff, clavecin - Robin Pharo, basse de viole MARIN MARAIS (1656-1728) - Pièces de viole 1 Prélude 2’16 2 Le Jeu du Volant 1,2 1’57 3 Le Petit Badinage 2’05 4 Le Rondeau Villeneuve 1,2 2’50 5 Rondeau Le Troilleur 1,2 4’07 6 Les Barricades Mystérieuses* François Couperin (1668-1733) 3’04 7 Prélude 1 2’47 8 Gavotte Singulière 1,2 1’50 9 Rondeau Le Bijou 1,2 4’15 10 Fête Champêtre 1 4’34 11 La Biscayenne 1,2 2’49 12 Le Badinage 6’19 13 La Paraza 1,2 3’54 14 Le Tact 1 1’50 15 Le Dodo ou l’Amour au Berceau* François Couperin 4’16 16 Rondeau Le Doucereux 1 5’06 17 La Provençale 1,2 3’08 18 La Rêveuse 6’19 * Transcription pour théorbe, Benjamin Perrot TRACKS 2 PLAGES CD LA RÊVEUSE Florence Bolton, basse de viole Benjamin Perrot, théorbe & guitare baroque (+ basse de viole « tact » dans Le Tact) Carsten Lohff, clavecin (1) Robin Pharo, basse de viole (2) Instruments Florence Bolton Basse de viole 7 cordes François Bodart 2010 d’après Barak Norman Archets Fausto Cangelosi – Craig Ryder Benjamin Perrot Théorbe Maurice Ottiger 2005 d’après Matteo Sellas Guitare baroque Stephen Murphy 2002 d’après Stradivari Carsten Lohff Clavecin Michel de Mayer 1998, d’après Pierre Donzelague 1716 Robin Pharo Basse de viole 7 cordes Judith Kraft 2012 d’après Guillaume Barbey Archet Pierre Patigny Enregistrement du 6 au 9 septembre 2016 au Château de Chambord, et le 13 juin 2017 à l’église de Franc-Waret (Belgique) (plages 6 et 15) / Prise de son et direction artistique : Hugues Deschaux / Montage numérique : Hugues Deschaux, Florence Bolton & Benjamin Perrot / Accord du clavecin : Thomas de Grunne / Administration et suivi de production La Rêveuse : Marion Paquier / Photos noir & blanc : Robin Davies / Conception et suivi artistique : René Martin, François-René Martin et Christian Meyrignac / Design : Jean-Michel Bouchet – LM Portfolio / Réalisation digipack : saga illico / Fabriqué par Sony DADC Austria / & © 2017 MIRARE, MIR386. -

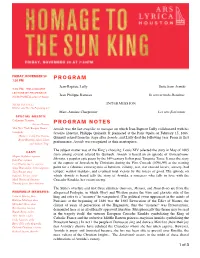

Sun King Program Notes

FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 20 PROGRAM 7:30 PM Jean-Baptiste Lully Suite from Armide 7:00 PM: PRE-CONCERT LECTURE BY PROFESSOR Jean-Philippe Rameau In convertendo Dominus JOHN POWELL (UNIV. OF TULSA) wfihe^=e^ii=L= INTERMISSION Hobby Center For The Performing Arts= Marc-Antoine Charpentier Les arts florissants SPECIAL GUESTS: Catherine Turocey, Artistic Director PROGRAM NOTES The New York Barque Dance Company Armide was the last tragédie en musique on which Jean-Baptiste Lully collaborated with his Dancers: Carly Fox Horton, favorite librettist, Philippe Quinault. It premiered at the Paris Opéra on February 15, 1686. Quinault retired from the stage after Armide, and Lully died the following year. From its first Brynt Beitman, Alexis Silver, and Andrew Trego performance, Armide was recognized as their masterpiece. The subject matter was of the King’s choosing: Louis XIV selected the story in May of 1685 CAST: Megan Stapleton, soprano from among several offered by Quinault. Armide is based on an episode of Gerusalemme Julia Fox, soprano liberata, a popular epic poem by the 16th-century Italian poet Torquato Tasso. It uses the story Cecy Duarte, mezzo-soprano of the capture of Jerusalem by Christians during the First Crusade (1096-99) as the starting Sonja Bruzauskas, mezzo-soprano point for a fabulous extravaganza of heroism, villainy, war, star-crossed lovers, sorcery, bad Tony Boutté, tenor temper, warrior maidens, and eventual total victory by the forces of good. The episode on Eduardo Tercero, tenor which Armide is based tells the story of Armida, a sorceress who falls in love with the Mark Diamond, baritone Crusader Rinaldo, her sworn enemy. -

M4^CHORAL UNION SERIES-Ms SIXTEENTH SEASON SECOND CONCERT (No

UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY F. W. KELSEY, President A. A. STANLEY, Director m4^CHORAL UNION SERIES-ms SIXTEENTH SEASON SECOND CONCERT (No. CXXXI1. Complete Series) University Hall, Thursday Evening, December 8, 1904 At Eight O'clock MUSIC OF BY-GONE CENTURIES Interpreted by Arnold Dolmetsch Mrs. Arnold Dolmetsch Miss Kathleen Salmon PROGRAM PART I 1. Two Pieces for the Lute i, Cascarda. ii. Canaries . Anonymous c iboo Mr. Arnold Dolmetsch 2. Song accompanied by the Lute " O Mistris Myne " .... Anonymous c, 1550 Miss Kathleen Salmon 3. A Piece for the Virginals "Muscadin" ..... Anonymous c. 1610 Mr Arnold Dolmetsch 4. Fantazie for Treble and Bass Viols " La Caccia" ..... Thomas Morley 1595 Mr. Arnold Dolmetsch. Mrs. Mabel Dolmetsch 5. Two Pieces for the Viola da Gamba accompanied by the Harpsichord i. Divisions On a Ground . Christopher Sympson 1656 ii. Prelude and Sarabande .... Marin Marais I6QS Mrs. Mabel Dolmetsch PART II 6. Two Pieces for the Harpsichord. i. " Le COUCOH" . Claude Daquin c. ijao ii. Sonata in A major .... Domenico Scarlatti c, 1720 Mr. Arnold Dolmetsch 7. Song, accompanied by the Harpsichord ** Qia il Sole" ... Alessandro Scarlatti c. 1700 Miss Kathleen Salmon 8. "The Harmonious Blacksmith," with variations for the Harpsichord . , G, F, Handel 1721 Miss Kathleen Salmon 9. Sonata for the Viola d'Amore, accompanied by the Harpsichord : Attilio Ariosto c. IJ15 Mr. Arnold Dolmetsch 10. "Troisieme Concert " for the Viola d'Amore, Viola da Gamba and Harpsichord i. «« La Lapopliniere," ii. " La Timide," Hi. Deux Tambourins . J. P. Rameau 1731 Mr. Arnold Dolmetsch Mrs. Mabel Dolmetsch Miss Kathleen Salmon The next Concert in the Choral Union Series will be given by The Kneisel Quartette, January 13, 1905, • Lockwood Lecture Recitals A series of six Historical lecture-Recitals will be given by Albert Lockwood, head of the Pianoforte Department of the University School of Music, on the following dates, at 4.30 p. -

Download Booklet

95779 The viola da gamba (or ‘leg-viol’) is so named because it is held between the legs. All the members of the 17th century, that the capabilities of the gamba as a solo instrument were most fully realised, of the viol family were similarly played in an upright position. The viola da gamba seems to especially in the works of Marin Marais and Antoine Forqueray (see below, CD7–13). have descended more directly from the medieval fiddle (known during the Middle Ages and early Born in London, John Dowland (1563–1626) became one of the most celebrated English Renaissance by such names as ffythele, ffidil, fiele or fithele) than the violin, but it is clear that composers of his day. His Lachrimæ, or Seaven Teares figured in Seaven Passionate Pavans were both violin and gamba families became established at about the same time, in the 16th century. published in London in 1604 when he was employed as lutenist at the court of the Danish King The differences in the gamba’s proportions, when compared with the violin family, may be Christian IV. These seven pavans are variations on a theme, the Lachrimae pavan, derived from summarised thus – a shorter sound box in relation to the length of the strings, wider ribs and a flat Dowland’s song Flow my tears. In his dedication Dowland observes that ‘The teares which Musicke back. Other ways in which the gamba differs from the violin include its six strings (later a seventh weeps [are not] always in sorrow but sometime in joy and gladnesse’. -

PROGRAM NOTES: Marin Marais

PROGRAM NOTES: Marin Marais (1656-1728) established himself as a virtuoso of the viola da gamba at a young age, earning the opportunity to study gamba with Monsieur de Saint Colombe and composition with Jean-Baptiste Lully. Marais became one of the most prolific composers of bass viola da gamba repertoire. Marais approached composition differently than his predecessors. Rather than leaving ornamentation to the discretion of the performer, Marais created his own system of symbols depicting specific graces. His desire to have complete control over every gesture stemmed from his studies with Lully, a composer who was also notorious for adding precise ornamentation instructions. La Gamme en forme d’un petit Opera (1723) is one of several trio sonatas Marais composed for violin, viola da gamba, and harpsichord. Each instrumental part in this piece is equally challenging, creating a contrast of virtuosic lines throughout each voice. The title “a scale in the form of a petit opera” suggests that Marais’ goal through this composition was to depict the same drama and variation as a short opera. Beginning in the key of C Major, Marais travels through each step of the scale to create these various operatic scenes. Unlike Marais’ earlier works, this piece has very few instructions on where to ornament. Therefore, the biggest challenge as a performer is finding ways to embellish nuances in order to depict the vast amounts of character changes that take place in this enormous work. Because the piece was composed in the last year of his life, Marais probable assumed anyone performing it would have studied his earlier music and would therefore understand the style of ornamentation he demands. -

Gerusalemme Liberata)) De Tass0 En La Genesi De ((L'atlantida))De Verdacuer

LA ((GERUSALEMME LIBERATA)) DE TASS0 EN LA GENESI DE ((L'ATLANTIDA))DE VERDACUER Rossend ARQUES ,És un fet prou sabut dels estudiosos que Verdaguer, quan residia a can Tona, escriví una carta al seu conegut Ferran Sellares, datada els primers dies de 1867, en que li comunicava que <(cada demati, entre vuit u nou horas, ja m hi veuria voste passejar amun y avall ab la Eneydu o la Geru.salem, que son las obras que may me cansí de llegir ni penso traure'm dels dits, y que han de ser la mort de la meva musa, pus veu quant esgarrifosos son, al costat dels seus, sos dibuixos.~IJosep M. de Casacuberta, en la nota 15 que comenta aquesta carta, escriu que ((L. C. Viada, en el treball abans citat, J. Verdaguer als Jocs Florals de Burcelonu, diu que I'accessit guanyat per Verdaguer al certamen del 1865 per la poesia L0.y minyons d'en Veciana consistí "en un exemplar de La Geru.salemme liheruta i L'Amintu del Tasso, que devora amb frui'cio I'estudiant-poeta", el qual en tragué un gran partit -afegeix Viada--en les seves temptatives epiques d'aquell -temps. Recordem que Jaume Collell, tan amic de Verdaguer, havia llegit la Gerusalemme: "no tenia encara quinze anys que en 10s solitaris recons de la Gorga, prop del Esquirol, recitava en veu alta" els seus cants (Del meu,fudrinatge, 1 15)~.~Malgrat les meves indagacions, no he pogut confirmar la noticia de Viada, pero sí, en canvi, el fet que aquest dos llibres de Tasso reunits en un sol volum (que avui es troba al fons Verdaguer de la Biblioteca de Catalunya3) foren una part del premi del concurs en que Verdaguer es va presentar amb L'Atlantida, és a dir, de I'any 1877. -

LULLY, J.: Armide (Opera Lafayette, 2007) Naxos 8.66020910 Jeanbaptiste Lully (1632 1687) Armide Tragé

LULLY, J.: Armide (Opera Lafayette, 2007) Naxos 8.66020910 JeanBaptiste Lully (1632 1687) Armide Tragédie en musique Libretto by Philippe Quinault, based on Torquato Tasso's La Gerusalemme liberata (Jerusalem Delivered), transcribed and adapted from Le théâtre de Mr Quinault, contenant ses tragédies, comédies et opéras (Paris: Pierre Ribou, 1715), vol. 5, pp. 389428. ACTE I ACT I Le théâtre représente une grande place ornée d’un arc de The scene represents a public place decorated with a Triumphal triomphe Arch. SCÈNE I SCENE I ARMIDE, PHÉNICE, SIDONIE ARMIDE, PHENICE, SIDONIE PHÉNICE PHENICE Dans un jour de triomphe, au milieu des plaisirs, On a day of victory, amid its pleasures, Qui peut vous inspirer une sombre tristesse? Who can inspire such dark sadness in you? La gloire, la grandeur, la beauté, la jeunesse, Glory, greatness, beauty, youth, Tous les biens comblent vos désirs. All these bounties fulfill your desires. SIDONIE SIDONIE Vous allumez une fatale flamme You spark a fatal flame Que vous ne ressentez jamais ; That you never feel: L’amour n’ose troubler la paix Love does not dare trouble the peace Qui règne dans votre âme. That reigns in your soul. ARMIDE, PHÉNICE et SIDONIE ensemble ARMIDE, PHENICE & SIDONIE together Quel sort a plus d’appâts? What fate is more desirable? Et qui peut être heureux si vous ne l’êtes pas? And who can be happy if you are not? PHÉNICE PHENICE Si la guerre aujourd’hui fait craindre ses ravages, If today war threatens its ravages, C’est aux bords du Jourdain qu’ils doivent s’arrêter. -

Passacaille of Armide

The ‘Passacaille of Armide’ Revisited: Rhetorical Aspects of Quinault’s / Lully’s tragédie en musique Kimiko Okamoto The tragédie en musique is a dramatic genre invented by for the effective deliverance of ideas. Oratory can strengthen Philippe Quinault and Jean-Baptiste Lully in the tradition of its impact by elaborating the usage of words, and to this end, French musical theatre; Armide was the last collaboration of techniques of word arrangement were systematised into those creators, and was first staged in 1686. The arch-shaped ‘figures’ and ‘tropes’; the former was absorbed into German (palindromic) symmetry of the verbal, musical and dramatic music theory, and named Figurenlehre. According to the structures of this genre has been pointed out by a number of Figurenlehre, musical motifs are manoeuvred in the same scholars,1 whereas few have discussed its rhetorical order, manner as words in oratory. Although dance treatises never another structural feature of seventeenth and early eight- mention rhetorical figures, the ways steps are arranged in the eenth-century compositions. Judith Schwartz was one of the notated choreographies bear a striking resemblance to these few to analyse the choreography of the ‘Passacaille’ from Act figures. A short sequence of steps often forms a choreo- V of Armide with reference to rhetorical structure.2 Notwith- graphic motif, which functions as a building block of a phrase standing, she applied the theory exclusively to choreogra- through repetition, enlargement, diminution and inversion – phy, leaving the music outside the rhetorical framework, just as the manipulation of words in speech and the manoeu- which Schwartz regarded as ‘asymmetry at odds with the vre of motifs in music. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title A Second Refuge: French Opera and the Huguenot Migration, c. 1680 - c. 1710 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6ck4p872 Author Ahrendt, Rebekah Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California A Second Refuge French Opera and the Huguenot Migration, c. 1680 – c. 1710 By Rebekah Susannah Ahrendt A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kate van Orden, Chair Professor Richard Taruskin Professor Peter Sahlins Fall 2011 A Second Refuge French Opera and the Huguenot Migration, c. 1680 – c. 1710 Copyright 2011 by Rebekah Susannah Ahrendt 1 Abstract A Second Refuge French Opera and the Huguenot Migration, c. 1680 – c. 1710 by Rebekah Susannah Ahrendt Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Kate van Orden, Chair This dissertation examines the brief flowering of French opera on stages outside of France around the turn of the eighteenth century. I attribute the sudden rise and fall of interest in the genre to a large and noisy migration event—the flight of some 200,000 Huguenots from France. Dispersed across Western Europe and beyond, Huguenots maintained extensive networks that encouraged the exchange of ideas and of music. And it was precisely in the great centers of the Second Refuge that French opera was performed. Following the wide-ranging career path of Huguenot impresario, novelist, poet, and spy Jean-Jacques Quesnot de la Chenée, I construct an alternative history of French opera by tracing its circulation and transformation along Huguenot migration routes.