Armide (Overture, and “Enfin, Il Est En Ma Puissance” with “Venez Seconder Mes Desires” from Act 2, Scene 5)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keyboard Arrangements of Music by Jean-Baptiste Lully: Introduction

Keyboard Arrangements of Music by Jean-Baptiste Lully, ed. David Chung, 2014 Introduction, p. i Abbreviations Bonfils 1974 Bonfils, Jean, ed. Livre d’orgue attribué à J.N. Geoffroy, Le Pupitre: no. 53. Paris: Heugel, 1974. Chung 1997 Chung, David. “Keyboard Arrangements and Their Significance for French Harpsichord Music.” 2 vols. PhD diss., University of Cambridge, 1997. Chung 2004 Chung, David, ed. Jean-Baptiste Lully: 27 brani d’opera transcritti per tastiera nei secc. XVII e XVIII. Bologna: UT Orpheus Edizioni, 2004. Gilbert 1975 Gilbert, Kenneth, ed. Jean-Henry d’Anglebert, Pièces de clavecin, Le Pupitre: no. 54. Paris: Heugel, 1975. Gustafson 1979 Gustafson, Bruce. French Harpsichord Music of the 17th Century: A Thematic Catalog of the Sources with Commentary. 3 vols. Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1979. Gustafson 2007 Gustafson, Bruce. Chambonnières: A Thematic Catalogue—The Complete Works of Jacques Champion de Chambonnières (1601/02–72), JSCM Instrumenta 1, 2007, r/2011. (http://sscm- jscm.org/instrumenta_01). Gustafson-Fuller 1990 Gustafson, Bruce and David Fuller. A Catalogue of French Harpsichord Music 1699-1780. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990. Harris 2009 Harris, C. David, ed. Jean Henry D’Anglebert: The Collected Works. New York: The Broude Trust, 2009. Howell 1963 Howell, Almonte Charles Jr., ed. Nine Seventeenth-Century Organ Transcriptions from the Operas of Lully. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1963. LWV Schneider, Herbert. Chronologisch-Thematisches Verzeichnis sämtlicher Werke von Jean-Baptiste Lully. Tutzing: Hans Schneider, 1981. WEB LIBRARY OF SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY MUSIC (www.sscm-wlscm.org) Monuments of Seventeenth-Century Music Vol. 1 Keyboard Arrangements of Music by Jean-Baptiste Lully, ed. -

Parte Il Celeberrimo ‘A Solo’ «Le Perfide Renaud Me Fuit»

La Scena e l’Ombra 13 Collana diretta da Paola Cosentino Comitato scientifico: Alberto Beniscelli Bianca Concolino Silvia Contarini Giuseppe Crimi Teresa Megale Lisa Sampson Elisabetta Selmi Stefano Verdino DOMENICO CHIODO ARMIDA DA TASSO A ROSSINI VECCHIARELLI EDITORE Pubblicato con il contributo dell’Università di Torino Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici © Vecchiarelli Editore S.r.l. – 2018 Piazza dell’Olmo, 27 00066 Manziana (Roma) Tel. e fax 06.99674591 [email protected] www.vecchiarellieditore.com ISBN 978-88-8247-419-5 Indice Armida nella Gerusalemme liberata 7 Le prime riscritture secentesche 25 La seconda metà del secolo 59 Il paradosso haendeliano e le Armide rococò 91 Ritorno a Parigi (passando per Vienna) 111 Ritorno a Napoli 123 La magia è il teatro 135 Bibliografia 145 Indice dei nomi 151 ARMIDA NELLA GERUSALEMME LIBERATA Per decenni, ma forse ancora oggi, tra i libri di testo in uso nella scuola secondaria per l’insegnamento letterario ha fatto la parte del leone il manuale intitolato Il materiale e l’immaginario: se lo si consulta alle pa- gine dedicate alla Gerusalemme liberata si può leggere che del poema «l’argomento è la conquista di Gerusalemme da parte dei crociati nel 1099» e che «Tasso scelse un argomento con caratteri non eruditi ma di attualità e a forte carica ideologica. Lo scontro fra l’Occidente cri- stiano e l’Islam - il tema della crociata - si rinnovava infatti per la mi- naccia dell’espansionismo turco in Europa e nel Mediterraneo». Tale immagine del poema consegnata alle attuali generazioni può conser- varsi soltanto a patto, come di fatto è, che non ne sia proprio prevista la lettura e viene da chiedersi che cosa avrebbero pensato di tali af- fermazioni gli europei dei secoli XVII e XVIII, ovvero dei secoli in cui la Liberata era lettura immancabile per qualunque europeo mediamen- te colto. -

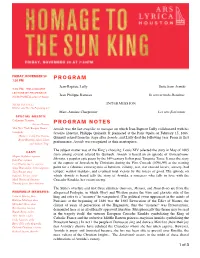

Sun King Program Notes

FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 20 PROGRAM 7:30 PM Jean-Baptiste Lully Suite from Armide 7:00 PM: PRE-CONCERT LECTURE BY PROFESSOR Jean-Philippe Rameau In convertendo Dominus JOHN POWELL (UNIV. OF TULSA) wfihe^=e^ii=L= INTERMISSION Hobby Center For The Performing Arts= Marc-Antoine Charpentier Les arts florissants SPECIAL GUESTS: Catherine Turocey, Artistic Director PROGRAM NOTES The New York Barque Dance Company Armide was the last tragédie en musique on which Jean-Baptiste Lully collaborated with his Dancers: Carly Fox Horton, favorite librettist, Philippe Quinault. It premiered at the Paris Opéra on February 15, 1686. Quinault retired from the stage after Armide, and Lully died the following year. From its first Brynt Beitman, Alexis Silver, and Andrew Trego performance, Armide was recognized as their masterpiece. The subject matter was of the King’s choosing: Louis XIV selected the story in May of 1685 CAST: Megan Stapleton, soprano from among several offered by Quinault. Armide is based on an episode of Gerusalemme Julia Fox, soprano liberata, a popular epic poem by the 16th-century Italian poet Torquato Tasso. It uses the story Cecy Duarte, mezzo-soprano of the capture of Jerusalem by Christians during the First Crusade (1096-99) as the starting Sonja Bruzauskas, mezzo-soprano point for a fabulous extravaganza of heroism, villainy, war, star-crossed lovers, sorcery, bad Tony Boutté, tenor temper, warrior maidens, and eventual total victory by the forces of good. The episode on Eduardo Tercero, tenor which Armide is based tells the story of Armida, a sorceress who falls in love with the Mark Diamond, baritone Crusader Rinaldo, her sworn enemy. -

Introduction: a Rich and Complex Heritage

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01237-0 - Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart Ralph P. Locke Excerpt More information part i Introduction: a rich and complex heritage © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01237-0 - Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart Ralph P. Locke Excerpt More information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01237-0 - Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart Ralph P. Locke Excerpt More information 1 Images and principles Images of Otherness This book tells two intertwined stories that have long needed to be told. It tells how Western music, during the years 1500–1800, reflected, reinforced, and sometimes challenged prevailing conceptions of unfamiliar lands – various Elsewheres – and their peoples. And it also tells how ideas about those locales and peoples contributed to the range and scope of musical works and musical life in the West (that is, in Europe and – to a lesser extent – its overseas colonies). For the most part, the book explores the ways in which those places and peoples were reflected in what we today consider musical works, ranging from operas and dramatic oratorios to foreign-derived instrumental dances such as a sarabande for lute or guitar. But it also explores other cultural products that – though not “musical works”–included a significant musical component: products as different as elaborate courtly ballets and cheaply printed -

Iphigénie En Tauride

Christoph Willibald Gluck Iphigénie en Tauride CONDUCTOR Tragedy in four acts Patrick Summers Libretto by Nicolas-François Guillard, after a work by Guymond de la Touche, itself based PRODUCTION Stephen Wadsworth on Euripides SET DESIGNER Saturday, February 26, 2011, 1:00–3:25 pm Thomas Lynch COSTUME DESIGNER Martin Pakledinaz LIGHTING DESIGNER Neil Peter Jampolis CHOREOGRAPHER The production of Iphigénie en Tauride was Daniel Pelzig made possible by a generous gift from Mr. and Mrs. Howard Solomon. Additional funding for this production was provided by Bertita and Guillermo L. Martinez and Barbara Augusta Teichert. The revival of this production was made possible by a GENERAL MANAGER gift from Barbara Augusta Teichert. Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine Iphigénie en Tauride is a co-production with Seattle Opera. 2010–11 Season The 17th Metropolitan Opera performance of Christoph Willibald Gluck’s Iphigénie en This performance is being broadcast Tauride live over The Toll Brothers– Metropolitan Conductor Opera Patrick Summers International Radio Network, in order of vocal appearance sponsored by Toll Brothers, Iphigénie America’s luxury Susan Graham homebuilder®, with generous First Priestess long-term Lei Xu* support from Second Priestess The Annenberg Cecelia Hall Foundation, the Vincent A. Stabile Thoas Endowment for Gordon Hawkins Broadcast Media, A Scythian Minister and contributions David Won** from listeners worldwide. Oreste Plácido Domingo This performance is Pylade also being broadcast Clytemnestre Paul Groves** Jacqueline Antaramian live on Metropolitan Opera Radio on Diane Agamemnon SIRIUS channel 78 Julie Boulianne Rob Besserer and XM channel 79. Saturday, February 26, 2011, 1:00–3:25 pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. -

The Italian Girl in Algiers

Opera Box Teacher’s Guide table of contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .8 Reference/Tracking Guide . .9 Lesson Plans . .11 Synopsis and Musical Excerpts . .32 Flow Charts . .38 Gioachino Rossini – a biography .............................45 Catalogue of Rossini’s Operas . .47 2 0 0 7 – 2 0 0 8 S E A S O N Background Notes . .50 World Events in 1813 ....................................55 History of Opera ........................................56 History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .67 GIUSEPPE VERDI SEPTEMBER 22 – 30, 2007 The Standard Repertory ...................................71 Elements of Opera .......................................72 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................76 GIOACHINO ROSSINI Glossary of Musical Terms .................................82 NOVEMBER 10 – 18, 2007 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .85 Word Search, Crossword Puzzle . .88 Evaluation . .91 Acknowledgements . .92 CHARLES GOUNOD JANUARY 26 –FEBRUARY 2, 2008 REINHARD KEISER MARCH 1 – 9, 2008 mnopera.org ANTONÍN DVOˇRÁK APRIL 12 – 20, 2008 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 The Italian Girl in Algiers Opera Box Lesson Plan Title Page with Related Academic Standards lesson title minnesota academic national standards standards: arts k–12 for music education 1 – Rossini – “I was born for opera buffa.” Music 9.1.1.3.1 8, 9 Music 9.1.1.3.2 Theater 9.1.1.4.2 Music 9.4.1.3.1 Music 9.4.1.3.2 Theater 9.4.1.4.1 Theater 9.4.1.4.2 2 – Rossini Opera Terms Music -

Program Notes.Docx

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE Pipe Organ Recital An abstract submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Music, Performance By Hae-Yul Grace Chung August 2014 The abstract of Hae-Yul Grace Chung is approved: _________________________________________ ______________ Dr. Elizabeth Sellers Date _________________________________________ ______________ Dr. Liviu Marinescu Date _________________________________________ ______________ Dr. Timothy Howard, Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ii Abstract iv 1. Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) 1 1.1 Analysis of Prelude and Fugue in A Minor, BWV 543 7 2. Dan Locklair (b.1949) 11 2. 1 Analysis of In Mystery and Wonder 12 3. Louis Vierne (1870-1937) 15 3. 1 Analysis of Troisième Symphonie Pour Grand Orgue 19 Bibliography 23 Appendix A: Map of Bach’s Travels 25 Appendix B: The Record of Bach’s Recommendations to repair 26 Appendix C: Specifications of the Notre Dame Organ 27 Appendix D: Themes in Troisième symphonie pour grand orgue 28 Appendix E: Recital Program 32 Appendix F: Recital Program Notes 35 iii ABSTRACT Pipe Organ Recital By Hae-Yul Grace Chung Master of Music, Performance The contributions made by Johann Sebastian Bach, Louis Vierne, and Dan Locklair hold a very distinct landmark in the development of organ music. Bach creatively brought Baroque music to its culmination, and is known for his expert contrapunctal craftsmanship that has proven itself through the ages. In the French Romantic period the zenith of symphonic organ music was achieved by Vierne through his six organ symphonies. Vierne modified sonata form, created subtle nuance in harmony, and utilized orchestral timbres made possible by the innovative organs of Aristide Cavaillé-Coll in the 19th century. -

Armide 1778 Gens Van Mechelen Christoyannis Santon Jeffery Watson Martin Wilder

LULLY ARMIDE 1778 GENS VAN MECHELEN CHRISTOYANNIS SANTON JEFFERY WATSON MARTIN WILDER LE CONCERT SPIRITUEL HERVÉ NIQUET SOMMAIRE | CONTENTS | INHALT ARMIDE, D’UN SIÈCLE À L’AUTRE PAR BENOÎT DRATWICKI p. 8 ARMIDE, FROM ONE CENTURY TO THE NEXT BY BENOÎT DRATWICKI p. 14 ARMIDE IM WANDEL DER JAHRHUNDERTE VON BENOÎT DRATWICKI p. 18 SYNOPSIS EN FRANÇAIS p. 28 SYNOPSIS IN ENGLISH p. 32 INHALTSANGABE p. 36 BIOGRAPHIES EN FRANÇAIS p. 40 BIOGRAPHIES IN ENGLISH p. 44 BIOGRAPHIEN p. 46 LIBRETTO p. 50 CRÉDITS, CREDITS, BEZETZUNG p. 77 6 7 LULLY ARMIDE TRAGÉDIE LYRIQUE EN UN PROLOGUE ET CINQ ACTES, CRÉÉE À L’ACADÉMIE ROYALE DE MUSIQUE À PARIS LE 15 FÉVRIER 1686, VERSION RÉVISÉE EN 1778 PAR LOUIS-JOSEPH FRANCŒUR MUSIQUE DE JEAN-BAPTISTE LULLY (1632-1687) ET LOUIS-JOSEPH FRANCŒUR (1738-1804) LIVRET DE PHILIPPE QUINAULT (1635-1688) VÉRONIQUE GENS ARMIDE REINOUD VAN MECHELEN RENAUD TASSIS CHRISTOYANNIS HIDRAOT, LA HAINE CHANTAL SANTON JEFFERY PHÉNICE, LUCINDE KATHERINE WATSON SIDONIE, UNE NAÏADE, UN PLAISIR PHILIPPE-NICOLAS MARTIN ARONTE, ARTÉMIDORE, UBALDE ZACHARY WILDER LE CHEVALIER DANOIS LE CONCERT SPIRITUEL CHŒUR ET ORCHESTRE HERVÉ NIQUET DIRECTION COPRODUCTION CENTRE DE MUSIQUE BAROQUE DE VERSAILLES, LE CONCERT SPIRITUEL PARTITION RÉALISÉE ET ÉDITÉE PAR LE CENTRE DE MUSIQUE BAROQUE DE VERSAILLES (JULIEN DUBRUQUE) LULLY ARMIDE CD1 CD2 ACTE I ACTE III 1 OUVERTURE 5’19 1 « Ah ! si la liberté me doit être ravie » ARMIDE 3’12 2 « Dans un jour de triomphe, au milieu des plaisirs » PHÉNICE, SIDONIE 2’45 2 « Que ne peut point votre art ? La force en est -

Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D Major, BWV No. 3 in D Major, BWV 1068

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Johann Sebastian Bach Born March 21, 1685, Eisenach, Thuringia, Germany. Died July 28, 1750, Leipzig, Germany. Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D Major, BWV 1068 Although the dating of Bach’s four orchestral suites is uncertain, the third was probably written in 1731. The score calls for two oboes, three trumpets, timpani, and harpsichord, with strings and basso continuo. Performance time is approximately twenty -one minutes. The Chicago Sympho ny Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Bach’s Third Orchestral Suite were given at the Auditorium Theatre on October 23 and 24, 1891, with Theodore Thomas conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on May 15 , 16, 17, and 20, 2003, with Jaime Laredo conducting. The Orchestra first performed the Air and Gavotte from this suite at the Ravinia Festival on June 29, 1941, with Frederick Stock conducting; the complete suite was first performed at Ravinia on August 5 , 1948, with Pierre Monteux conducting, and most recently on August 28, 2000, with Vladimir Feltsman conducting. When the young Mendelssohn played the first movement of Bach’s Third Orchestral Suite on the piano for Goethe, the poet said he could see “a p rocession of elegantly dressed people proceeding down a great staircase.” Bach’s music was nearly forgotten in 1830, and Goethe, never having heard this suite before, can be forgiven for wanting to attach a visual image to such stately and sweeping music. Today it’s hard to imagine a time when Bach’s name meant little to music lovers and when these four orchestral suites weren’t considered landmarks. -

"Mixed Taste," Cosmopolitanism, and Intertextuality in Georg Philipp

“MIXED TASTE,” COSMOPOLITANISM, AND INTERTEXTUALITY IN GEORG PHILIPP TELEMANN’S OPERA ORPHEUS Robert A. Rue A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2017 Committee: Arne Spohr, Advisor Mary Natvig Gregory Decker © 2017 Robert A. Rue All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Arne Spohr, Advisor Musicologists have been debating the concept of European national music styles in the Baroque period for nearly 300 years. But what precisely constitutes these so-called French, Italian, and German “tastes”? Furthermore, how do contemporary sources confront this issue and how do they delineate these musical constructs? In his Music for a Mixed Taste (2008), Steven Zohn achieves success in identifying musical tastes in some of Georg Phillip Telemann’s instrumental music. However, instrumental music comprises only a portion of Telemann’s musical output. My thesis follows Zohn’s work by identifying these same national styles in opera: namely, Telemann’s Orpheus (Hamburg, 1726), in which the composer sets French, Italian, and German texts to music. I argue that though identifying the interrelation between elements of musical style and the use of specific languages, we will have a better understanding of what Telemann and his contemporaries thought of as national tastes. I will begin my examination by identifying some of the issues surrounding a selection of contemporary treatises, in order explicate the problems and benefits of their use. These sources include Johann Joachim Quantz’s Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte zu spielen (1752), two of Telemann’s autobiographies (1718 and 1740), and Johann Adolf Scheibe’s Critischer Musikus (1737). -

The Recorded Examples Les Illustrations Sonores

The recorded examples The eight CDs that accompany this treatise follow its argument closely. Lengthy works or those on a large scale are represented by a few well-chosen excerpts; we have also chosen to refer the listener to certain complete recordings that are easily available through normal commercial channels. The greatest performers of our time have devoted their talents to making these works live again; some of these works have also enjoyed stage revivals, as was the case with Lully’s Atys, conducted by William Christie and directed by Jean-Marie Villégier in 1987 in a staging that has since become legendary. More recently, the young conductor Sébastien Daucé has presented the first reconstruction of aballet de cour, the Ballet royal de la Nuit. Les illustrations sonores Les huit disques qui accompagnent cet ouvrage suivent pas à pas le cours de ce récit. En ce qui concerne les œuvres de grande envergure, elles ne sont illustrées ici que par quelques extraits représentatifs. Il convient évidemment de se référer aux quelques enregistrements complets qui sont disponibles sur le marché du disque. Les plus grands interprètes de notre époque ont apporté tout leur talent à faire revivre ces ouvrages, bénéficiant parfois aussi de la possibilité d’une représentation scénique, comme ce fut le cas pour Atys de Lully, dont le spectacle dirigé par William Christie pour la musique et par Jean-Marie Villégier pour la mise en scène fut, en 1987, un événement mémorable. Tout récemment, c’est le jeune chef Sébastien Daucé qui a proposé la première reconstitution d’un ballet de cour, Le Ballet royal de la Nuit… 140 CD I AIRS DE COUR & BALLETS DE COUR 1. -

LULLY, J.: Armide (Opera Lafayette, 2007) Naxos 8.66020910 Jeanbaptiste Lully (1632 1687) Armide Tragé

LULLY, J.: Armide (Opera Lafayette, 2007) Naxos 8.66020910 JeanBaptiste Lully (1632 1687) Armide Tragédie en musique Libretto by Philippe Quinault, based on Torquato Tasso's La Gerusalemme liberata (Jerusalem Delivered), transcribed and adapted from Le théâtre de Mr Quinault, contenant ses tragédies, comédies et opéras (Paris: Pierre Ribou, 1715), vol. 5, pp. 389428. ACTE I ACT I Le théâtre représente une grande place ornée d’un arc de The scene represents a public place decorated with a Triumphal triomphe Arch. SCÈNE I SCENE I ARMIDE, PHÉNICE, SIDONIE ARMIDE, PHENICE, SIDONIE PHÉNICE PHENICE Dans un jour de triomphe, au milieu des plaisirs, On a day of victory, amid its pleasures, Qui peut vous inspirer une sombre tristesse? Who can inspire such dark sadness in you? La gloire, la grandeur, la beauté, la jeunesse, Glory, greatness, beauty, youth, Tous les biens comblent vos désirs. All these bounties fulfill your desires. SIDONIE SIDONIE Vous allumez une fatale flamme You spark a fatal flame Que vous ne ressentez jamais ; That you never feel: L’amour n’ose troubler la paix Love does not dare trouble the peace Qui règne dans votre âme. That reigns in your soul. ARMIDE, PHÉNICE et SIDONIE ensemble ARMIDE, PHENICE & SIDONIE together Quel sort a plus d’appâts? What fate is more desirable? Et qui peut être heureux si vous ne l’êtes pas? And who can be happy if you are not? PHÉNICE PHENICE Si la guerre aujourd’hui fait craindre ses ravages, If today war threatens its ravages, C’est aux bords du Jourdain qu’ils doivent s’arrêter.