Gluck (Part II)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conflict of Obligations in Euripides' Alcestis

GOLDFARB, BARRY E., The Conflict of Obligations in Euripides' "Alcestis" , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 33:2 (1992:Summer) p.109 The Conflict of Obligations in Euripides' Alcestis Barry E. Goldfarb 0UT ALCESTIS A. M. Dale has remarked that "Perhaps no f{other play of Euripides except the Bacchae has provoked so much controversy among scholars in search of its 'real meaning'."l I hope to contribute to this controversy by an examination of the philosophical issues underlying the drama. A radical tension between the values of philia and xenia con stitutes, as we shall see, a major issue within the play, with ramifications beyond the Alcestis and, in fact, beyond Greek tragedy in general: for this conflict between two seemingly autonomous value-systems conveys a stronger sense of life's limitations than its possibilities. I The scene that provides perhaps the most critical test for an analysis of Alcestis is the concluding one, the 'happy ending'. One way of reading the play sees this resolution as ironic. According to Wesley Smith, for example, "The spectators at first are led to expect that the restoration of Alcestis is to depend on a show of virtue by Admetus. And by a fine stroke Euripides arranges that the restoration itself is the test. At the crucial moment Admetus fails the test.'2 On this interpretation 1 Euripides, Alcestis (Oxford 1954: hereafter 'Dale') xviii. All citations are from this editon. 2 W. D. Smith, "The Ironic Structure in Alcestis," Phoenix 14 (1960) 127-45 (=]. R. Wisdom, ed., Twentieth Century Interpretations of Euripides' Alcestis: A Collection of Critical Essays [Englewood Cliffs 1968]) 37-56 at 56. -

Hercules: Celebrity Strongman Or Kindly Deliverer?

Hercules: Celebrity Strongman or Kindly Deliverer? BY J. LARAE FERGUSON When Christoph Willibald Gluck’s French Alceste premiered in Paris on 23 April 1776, the work met with mixed responses. Although the French audience loved the first and second acts for their masterful staging and thrilling presentation, to them the third act seemed unappealing, a mere tedious extension of what had come before it. Consequently, Gluck and his French librettist Lebland Du Roullet returned to the drawing board. Within a mere two weeks, however, their alterations were complete. The introduction of the character Hercules, a move which Gluck had previously contemplated but never actualized, transformed the denouement and eventually brought the opera to its final popular acclaim. Despite Gluck’s sagacious wager that adding the character of Hercules would give to his opera the variety demanded by his French audience, many of his followers then and now admit that something about the character does not fit, something of the essential nature of the drama is lost by Hercules’ abrupt insertion. Further, although many of Gluck’s supporters maintain that his encouragement of Du Roullet to reinstate Hercules points to his acknowledged desire to adhere to the original Greek tragedy from which his opera takes its inspiration1, a close examination of the relationship between Gluck’s Hercules and Euripides’ Heracles brings to light marked differences in the actions, the purpose, and the characterization of the two heroes. 1 Patricia Howard, for instance, writes that “the difference between Du Roullet’s libretto and Calzabigi’s suggests that Gluck might have been genuinely dissatisfied at the butchery Calzabigi effected on Euripides, and his second version was an attempt not so much at a more French drama as at a more classically Greek one.” Patricia Howard, “Gluck’s Two Alcestes: A Comparison,” Musical Times 115 (1974): 642. -

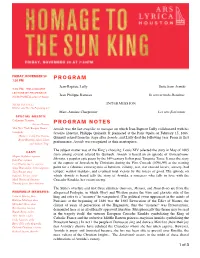

Sun King Program Notes

FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 20 PROGRAM 7:30 PM Jean-Baptiste Lully Suite from Armide 7:00 PM: PRE-CONCERT LECTURE BY PROFESSOR Jean-Philippe Rameau In convertendo Dominus JOHN POWELL (UNIV. OF TULSA) wfihe^=e^ii=L= INTERMISSION Hobby Center For The Performing Arts= Marc-Antoine Charpentier Les arts florissants SPECIAL GUESTS: Catherine Turocey, Artistic Director PROGRAM NOTES The New York Barque Dance Company Armide was the last tragédie en musique on which Jean-Baptiste Lully collaborated with his Dancers: Carly Fox Horton, favorite librettist, Philippe Quinault. It premiered at the Paris Opéra on February 15, 1686. Quinault retired from the stage after Armide, and Lully died the following year. From its first Brynt Beitman, Alexis Silver, and Andrew Trego performance, Armide was recognized as their masterpiece. The subject matter was of the King’s choosing: Louis XIV selected the story in May of 1685 CAST: Megan Stapleton, soprano from among several offered by Quinault. Armide is based on an episode of Gerusalemme Julia Fox, soprano liberata, a popular epic poem by the 16th-century Italian poet Torquato Tasso. It uses the story Cecy Duarte, mezzo-soprano of the capture of Jerusalem by Christians during the First Crusade (1096-99) as the starting Sonja Bruzauskas, mezzo-soprano point for a fabulous extravaganza of heroism, villainy, war, star-crossed lovers, sorcery, bad Tony Boutté, tenor temper, warrior maidens, and eventual total victory by the forces of good. The episode on Eduardo Tercero, tenor which Armide is based tells the story of Armida, a sorceress who falls in love with the Mark Diamond, baritone Crusader Rinaldo, her sworn enemy. -

Introduction: a Rich and Complex Heritage

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01237-0 - Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart Ralph P. Locke Excerpt More information part i Introduction: a rich and complex heritage © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01237-0 - Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart Ralph P. Locke Excerpt More information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01237-0 - Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart Ralph P. Locke Excerpt More information 1 Images and principles Images of Otherness This book tells two intertwined stories that have long needed to be told. It tells how Western music, during the years 1500–1800, reflected, reinforced, and sometimes challenged prevailing conceptions of unfamiliar lands – various Elsewheres – and their peoples. And it also tells how ideas about those locales and peoples contributed to the range and scope of musical works and musical life in the West (that is, in Europe and – to a lesser extent – its overseas colonies). For the most part, the book explores the ways in which those places and peoples were reflected in what we today consider musical works, ranging from operas and dramatic oratorios to foreign-derived instrumental dances such as a sarabande for lute or guitar. But it also explores other cultural products that – though not “musical works”–included a significant musical component: products as different as elaborate courtly ballets and cheaply printed -

Winged Feet and Mute Eloquence: Dance In

Winged Feet and Mute Eloquence: Dance in Seventeenth-Century Venetian Opera Author(s): Irene Alm, Wendy Heller and Rebecca Harris-Warrick Source: Cambridge Opera Journal, Vol. 15, No. 3 (Nov., 2003), pp. 216-280 Published by: Cambridge University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3878252 Accessed: 05-06-2015 15:05 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3878252?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Cambridge Opera Journal. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.112.200.107 on Fri, 05 Jun 2015 15:05:41 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions CambridgeOpera Journal, 15, 3, 216-280 ( 2003 CambridgeUniversity Press DOL 10.1017/S0954586703001733 Winged feet and mute eloquence: dance in seventeenth-century Venetian opera IRENE ALM (edited by Wendy Heller and Rebecca Harris-Warrick) Abstract: This article shows how central dance was to the experience of opera in seventeenth-centuryVenice. -

Iphigénie En Tauride

Christoph Willibald Gluck Iphigénie en Tauride CONDUCTOR Tragedy in four acts Patrick Summers Libretto by Nicolas-François Guillard, after a work by Guymond de la Touche, itself based PRODUCTION Stephen Wadsworth on Euripides SET DESIGNER Saturday, February 26, 2011, 1:00–3:25 pm Thomas Lynch COSTUME DESIGNER Martin Pakledinaz LIGHTING DESIGNER Neil Peter Jampolis CHOREOGRAPHER The production of Iphigénie en Tauride was Daniel Pelzig made possible by a generous gift from Mr. and Mrs. Howard Solomon. Additional funding for this production was provided by Bertita and Guillermo L. Martinez and Barbara Augusta Teichert. The revival of this production was made possible by a GENERAL MANAGER gift from Barbara Augusta Teichert. Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine Iphigénie en Tauride is a co-production with Seattle Opera. 2010–11 Season The 17th Metropolitan Opera performance of Christoph Willibald Gluck’s Iphigénie en This performance is being broadcast Tauride live over The Toll Brothers– Metropolitan Conductor Opera Patrick Summers International Radio Network, in order of vocal appearance sponsored by Toll Brothers, Iphigénie America’s luxury Susan Graham homebuilder®, with generous First Priestess long-term Lei Xu* support from Second Priestess The Annenberg Cecelia Hall Foundation, the Vincent A. Stabile Thoas Endowment for Gordon Hawkins Broadcast Media, A Scythian Minister and contributions David Won** from listeners worldwide. Oreste Plácido Domingo This performance is Pylade also being broadcast Clytemnestre Paul Groves** Jacqueline Antaramian live on Metropolitan Opera Radio on Diane Agamemnon SIRIUS channel 78 Julie Boulianne Rob Besserer and XM channel 79. Saturday, February 26, 2011, 1:00–3:25 pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. -

Howard Mayer Brown Microfilm Collection Guide

HOWARD MAYER BROWN MICROFILM COLLECTION GUIDE Page individual reels from general collections using the call number: Howard Mayer Brown microfilm # ___ Scope and Content Howard Mayer Brown (1930 1993), leading medieval and renaissance musicologist, most recently ofthe University ofChicago, directed considerable resources to the microfilming ofearly music sources. This collection ofmanuscripts and printed works in 1700 microfilms covers the thirteenth through nineteenth centuries, with the bulk treating the Medieval, Renaissance, and early Baroque period (before 1700). It includes medieval chants, renaissance lute tablature, Venetian madrigals, medieval French chansons, French Renaissance songs, sixteenth to seventeenth century Italian madrigals, eighteenth century opera libretti, copies ofopera manuscripts, fifteenth century missals, books ofhours, graduals, and selected theatrical works. I Organization The collection is organized according to the microfilm listing Brown compiled, and is not formally cataloged. Entries vary in detail; some include RISM numbers which can be used to find a complete description ofthe work, other works are identified only by the library and shelf mark, and still others will require going to the microfilm reel for proper identification. There are a few microfilm reel numbers which are not included in this listing. Brown's microfilm collection guide can be divided roughly into the following categories CONTENT MICROFILM # GUIDE Works by RISM number Reels 1- 281 pp. 1 - 38 Copies ofmanuscripts arranged Reels 282-455 pp. 39 - 49 alphabetically by institution I Copies of manuscript collections and Reels 456 - 1103 pp. 49 - 84 . miscellaneous compositions I Operas alphabetical by composer Reels 11 03 - 1126 pp. 85 - 154 I IAnonymous Operas i Reels 1126a - 1126b pp.155-158 I I ILibretti by institution Reels 1127 - 1259 pp. -

Armide 1778 Gens Van Mechelen Christoyannis Santon Jeffery Watson Martin Wilder

LULLY ARMIDE 1778 GENS VAN MECHELEN CHRISTOYANNIS SANTON JEFFERY WATSON MARTIN WILDER LE CONCERT SPIRITUEL HERVÉ NIQUET SOMMAIRE | CONTENTS | INHALT ARMIDE, D’UN SIÈCLE À L’AUTRE PAR BENOÎT DRATWICKI p. 8 ARMIDE, FROM ONE CENTURY TO THE NEXT BY BENOÎT DRATWICKI p. 14 ARMIDE IM WANDEL DER JAHRHUNDERTE VON BENOÎT DRATWICKI p. 18 SYNOPSIS EN FRANÇAIS p. 28 SYNOPSIS IN ENGLISH p. 32 INHALTSANGABE p. 36 BIOGRAPHIES EN FRANÇAIS p. 40 BIOGRAPHIES IN ENGLISH p. 44 BIOGRAPHIEN p. 46 LIBRETTO p. 50 CRÉDITS, CREDITS, BEZETZUNG p. 77 6 7 LULLY ARMIDE TRAGÉDIE LYRIQUE EN UN PROLOGUE ET CINQ ACTES, CRÉÉE À L’ACADÉMIE ROYALE DE MUSIQUE À PARIS LE 15 FÉVRIER 1686, VERSION RÉVISÉE EN 1778 PAR LOUIS-JOSEPH FRANCŒUR MUSIQUE DE JEAN-BAPTISTE LULLY (1632-1687) ET LOUIS-JOSEPH FRANCŒUR (1738-1804) LIVRET DE PHILIPPE QUINAULT (1635-1688) VÉRONIQUE GENS ARMIDE REINOUD VAN MECHELEN RENAUD TASSIS CHRISTOYANNIS HIDRAOT, LA HAINE CHANTAL SANTON JEFFERY PHÉNICE, LUCINDE KATHERINE WATSON SIDONIE, UNE NAÏADE, UN PLAISIR PHILIPPE-NICOLAS MARTIN ARONTE, ARTÉMIDORE, UBALDE ZACHARY WILDER LE CHEVALIER DANOIS LE CONCERT SPIRITUEL CHŒUR ET ORCHESTRE HERVÉ NIQUET DIRECTION COPRODUCTION CENTRE DE MUSIQUE BAROQUE DE VERSAILLES, LE CONCERT SPIRITUEL PARTITION RÉALISÉE ET ÉDITÉE PAR LE CENTRE DE MUSIQUE BAROQUE DE VERSAILLES (JULIEN DUBRUQUE) LULLY ARMIDE CD1 CD2 ACTE I ACTE III 1 OUVERTURE 5’19 1 « Ah ! si la liberté me doit être ravie » ARMIDE 3’12 2 « Dans un jour de triomphe, au milieu des plaisirs » PHÉNICE, SIDONIE 2’45 2 « Que ne peut point votre art ? La force en est -

LULLY, J.: Armide (Opera Lafayette, 2007) Naxos 8.66020910 Jeanbaptiste Lully (1632 1687) Armide Tragé

LULLY, J.: Armide (Opera Lafayette, 2007) Naxos 8.66020910 JeanBaptiste Lully (1632 1687) Armide Tragédie en musique Libretto by Philippe Quinault, based on Torquato Tasso's La Gerusalemme liberata (Jerusalem Delivered), transcribed and adapted from Le théâtre de Mr Quinault, contenant ses tragédies, comédies et opéras (Paris: Pierre Ribou, 1715), vol. 5, pp. 389428. ACTE I ACT I Le théâtre représente une grande place ornée d’un arc de The scene represents a public place decorated with a Triumphal triomphe Arch. SCÈNE I SCENE I ARMIDE, PHÉNICE, SIDONIE ARMIDE, PHENICE, SIDONIE PHÉNICE PHENICE Dans un jour de triomphe, au milieu des plaisirs, On a day of victory, amid its pleasures, Qui peut vous inspirer une sombre tristesse? Who can inspire such dark sadness in you? La gloire, la grandeur, la beauté, la jeunesse, Glory, greatness, beauty, youth, Tous les biens comblent vos désirs. All these bounties fulfill your desires. SIDONIE SIDONIE Vous allumez une fatale flamme You spark a fatal flame Que vous ne ressentez jamais ; That you never feel: L’amour n’ose troubler la paix Love does not dare trouble the peace Qui règne dans votre âme. That reigns in your soul. ARMIDE, PHÉNICE et SIDONIE ensemble ARMIDE, PHENICE & SIDONIE together Quel sort a plus d’appâts? What fate is more desirable? Et qui peut être heureux si vous ne l’êtes pas? And who can be happy if you are not? PHÉNICE PHENICE Si la guerre aujourd’hui fait craindre ses ravages, If today war threatens its ravages, C’est aux bords du Jourdain qu’ils doivent s’arrêter. -

METASTASIO COLLECTION at WESTERN UNIVERSITY Works Intended for Musical Setting Scores, Editions, Librettos, and Translations In

METASTASIO COLLECTION AT WESTERN UNIVERSITY Works Intended for Musical Setting Scores, Editions, Librettos, and Translations in the Holdings of the Music Library, Western University [London, Ontario] ABOS, Girolamo Alessandro nell’Indie (Ancona 1747) (Eighteenth century) – (Microfilm of Ms. Score) (From London: British Library [Add. Ms. 14183]) Aria: “Se amore a questo petto” (Alessandro [v.1] Act 1, Sc.15) [P.S.M. Ital. Mus. Ms. Sec.A, Pt.1, reel 8] ABOS, Girolamo Artaserse (Venice 1746) (Mid-eighteenth century) – (Microfilm of Ms. Score) (From London: British Library [Add. Ms. 31655]) Aria: “Mi credi spietata?” (Mandane, Act 3, Sc.5) [P.S.M. Ital. Mus. Ms. Sec.C, Pt.2, reel 27] ADOLFATI, Andrea Didone abbandonata (with puppets – Venice 1747) (Venice 1747) – (Venice: Luigi Pavini, 1747) – (Libretto) [W.U. Schatz 57, reel 2] AGRICOLA, Johann Friedrich Achille in Sciro (Berlin 1765) (Berlin 1765) – (Berlin: Haude e Spener, 1765) – (Libretto) (With German rendition as Achilles in Scirus) [W.U. Schatz 66, reel 2] AGRICOLA, Johann Friedrich Alessandro nell’Indie (as Cleofide – Berlin 1754) (Berlin 1754) – (Berlin: Haude e Spener, [1754]) – (Libretto) (With German rendition as Cleofide) [W.U. Schatz 67, reel 2] ALBERTI, Domenico L’olimpiade (no full setting) (Eighteenth century) – (Microfilm of Ms. Score) (From London: British Library [R.M.23.e.2 (1)]) Aria: “Che non mi disse un dì!” (Argene, Act 2, Sc.4) [P.S.M. Ital. Mus. Ms. Sec.B, Pt.4, reel 73] ALBERTI, Domenico Temistocle (no full setting) (Eighteenth century) – (Microfilm of Ms. Score) 2 (From London: British Library [R.M.23.c.19]) Aria: “Ah! frenate il pianto imbelle” (Temistocle, Act 3, Sc.3) [P.S.M. -

NOTES on GLUCK's ARMIDE by CARL VAN VECHTEN ICHARD WAGNER, Like Many Another Great Man, Took

NOTES ON GLUCK'S ARMIDE By CARL VAN VECHTEN ICHARD WAGNER, like many another great man, took what he wanted where he found it. Everyone has heard Downloaded from R the story of his remark to his father-in-law when that august musician first listened to Die WalkHre: "You will recognize this theme, Papa Liszt?" The motto in question occurs when Sieglinde sings: Kehrte der Voder nun heim. Liszt had used the tune at the beginning of his Faust symphony. Not long ago, in http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ playing over Schumann's Kinderscenen, I discovered Brunnhilde's magic slumber music, exactly as it appears in the music drama, in the piece pertinently called Kind im Einschlummern. When Weber's Euryanihe was revived recently at the Metropolitan Opera House it had the appearance of an old friend, although comparatively few in the first night audience had heard the opera before. One recognized tunes, characters, and scenes, because Wagner had found them all good enough to use in Tannh&user at University of Toronto Library on July 15, 2015 and Lohengrin. 'But, at least, you will object, he invented the music drama. That, I am inclined to believe, is just what he did not do, as anyone may see for himself who will take the trouble to glance over the scores of the Chevalier Gluck and to read the preface to Alceste. Gluck's reform of the opera was gradual; Orphie (in its French version), Alceste, and IphigSnie en Aulide, all of which antedate Armide, are replete with indications of what was to come; but Armide, it seems to me, is, in intention at least, almost the music drama, as we use the term to-day. -

The Mezzo-Soprano Onstage and Offstage: a Cultural History of the Voice-Type, Singers and Roles in the French Third Republic (1870–1918)

The mezzo-soprano onstage and offstage: a cultural history of the voice-type, singers and roles in the French Third Republic (1870–1918) Emma Higgins Dissertation submitted to Maynooth University in fulfilment for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Maynooth University Music Department October 2015 Head of Department: Professor Christopher Morris Supervisor: Dr Laura Watson 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page number SUMMARY 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 4 LIST OF FIGURES 5 LIST OF TABLES 5 INTRODUCTION 6 CHAPTER ONE: THE MEZZO-SOPRANO AS A THIRD- 19 REPUBLIC PROFESSIONAL MUSICIAN 1.1: Techniques and training 19 1.2: Professional life in the Opéra and the Opéra-Comique 59 CHAPTER TWO: THE MEZZO-SOPRANO ROLE AND ITS 99 RELATIONSHIP WITH THIRD-REPUBLIC SOCIETY 2.1: Bizet’s Carmen and Third-Republic mores 102 2.2: Saint-Saëns’ Samson et Dalila, exoticism, Catholicism and patriotism 132 2.3: Massenet’s Werther, infidelity and maternity 160 CHAPTER THREE: THE MEZZO-SOPRANO AS MUSE 188 3.1: Introduction: the muse/musician concept 188 3.2: Célestine Galli-Marié and Georges Bizet 194 3.3: Marie Delna and Benjamin Godard 221 3.3.1: La Vivandière’s conception and premieres: 1893–95 221 3.3.2: La Vivandière in peace and war: 1895–2013 240 3.4: Lucy Arbell and Jules Massenet 252 3.4.1: Arbell the self-constructed Muse 252 3.4.2: Le procès de Mlle Lucy Arbell – the fight for Cléopâtre and Amadis 268 CONCLUSION 280 BIBLIOGRAPHY 287 APPENDICES 305 2 SUMMARY This dissertation discusses the mezzo-soprano singer and her repertoire in the Parisian Opéra and Opéra-Comique companies between 1870 and 1918.