University of Hawai'i Library the Girl with Pomegranate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

Record World Sales Iintder Motion for a Temporary Re- Straining Order Blocking the Single's Release

NEWSPAPER ISSN 0034-1622 Ztilea...," 1.1(12,Lic:c. SEPTEMBER 20, 1980 $2. Stephanie Mills A Saluteto to Teddy Pendergrass SINGLES ALBUMS DONNA SUMMER, "THE WANDERER" STEVIE WONDER, "MASTER BLASTER THE B -52's, "WILD PLANET." The (prod. by Moroder-Bellotte) (JAMMIN')" (prod. by Wonder) idiosyncratic Georgia quintet's de- (G M PC / Sweet Summer Night, (writer: Wonder) (Jobete/Black but LP was an AOR and club sleep- ASCAP) (3:44). One of Summer's Bull, ASCAP) (4:49). Blending er that wouldn't stop selling, and most eclectic outings. She draws topical urban street themes with their second album indicates that from numerous influences to cre- reggae -pop rhythms, Wonder the relentless, dance - crazed ate a seductive rocker. Vocal creates a compelling single from rhythms haven't stopped either. In- quivers & keyboard vamps do the his forthcoming "Hotter Than cludes "Private Idaho." Warner job. Geffen 49563 (WB). July" LP. Tamla 54317 (Motown). Bros. BSK 3471 (7.98). SUPERTRAMP, "DREAMER" (prod. by KANSAS, "HOLD ON" (prod. by group) GARY NUMAN, "TELEKON." Numan Henderson -Pope) (writers: Da- (writer: Livgren) (Don Kirshner/ may not have been the first prac- vies -Hodgson) (Almo/Delicate, Blackwood, BMI) (3:45). From titioner of techno-pop, but his sim- ASCAP) (3:15). This live cut from the new "Audio -Visions" LP plified approach and lilting lyric the forthcoming double -LP set comes this ballad with a recur- patterns seem to be the most ideally is a to get cinch immediate pop ring surge of power at the hook. suited to pop radio formats, as indi- reaction. -

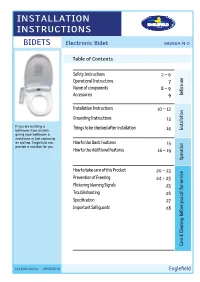

Installation Instructions

INSTALLATION INSTRUCTIONS BIDETS Electronic Bidet 99286A-N-0 Table of Contents Safety Instructions 2 ~ 6 Operational Instructions 7 Name of components 8 ~ 9 Accessories 9 use Before Precautions Installation Instructions 10 ~ 12 Grounding Instructions 13 If you are building a Things to be checked after installation Installation bathroom from scratch, 14 giving your bathroom a Installation makeover or just replacing an old tap, Englefield can How to Use Basic Features 15 provide a solution for you. How to Use Additional Features 16 ~ 19 Operation How to use to How How to take care of this Product 20 ~ 23 Prevention of Freezing 24 ~ 25 Flickering Warning Signals 25 Troubleshooting 26 Specification 27 Important Safeguards 28 Maintenance Care & Cleaning. Before you call for service for call you Before Cleaning. & Care 1243065-A02-A 29/02/2016 Englefield Safety Instructions Be sure to observe the following Be sure to read the following safety instructions carefully and use the product only as instructed in this manual to prevent bodily injuries and/or property damage which might happen while using this product. Failure to observe any of the Failure to observe any of the WARNING following might result in CAUTION following might result in minor critical injury or death. injury and/or product damage. Be sure to unplug the electric Strictly prohibited. power plug. Never disassemble or modify this Do not place in or drop into water. product. Proper grounding required to Things that have to be observed. Never use wet hands. *1 : Serious injury includes loss of eyesight, severe wound, burn (high, low temperature), electric shock, bone fracture, etc. -

Keith Jarrett's Spiritual Beliefs Through a Gurdjieffian Lens

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals... Channelling the Creative: Keith Jarrett’s Spiritual Beliefs Through a Gurdjieffian Lens Johanna Petsche Introduction The elusive nature of the creative process in art has remained a puzzling phenomenon for artists and their audiences. What happens to an inspired artist in the moment of creation and where that inspiration comes from are questions that prompt many artists to explain the process as spiritual or mystical, describing their experiences as ‘channelling the divine’, ‘tapping into a greater reality’, or being visited or played by their ‘muse’. Pianist and improviser Keith Jarrett (b.1945) frequently explains the creative process in this way and this is nowhere more evident than in discussions on his wholly improvised solo concerts. Jarrett explains these massive feats of creativity in terms of an ability to ‘channel’ or ‘surrender to’ a source of inspiration, which he ambiguously designates the ‘ongoing harmony’, the ‘Creative’, and the ‘Divine Will’. These accounts are freely expressed in interviews and album liner notes, and are thus highly accessible to his audiences. Jarrett’s mystical accounts of the creative process, his incredible improvisatory abilities, and other key elements come together to create the strange aura of mystery that surrounds his notorious solo concerts. This paper will demystify Jarrett’s spiritual beliefs on the creative process by considering them within a Gurdjieffian context. This will allow for a much deeper understanding of Jarrett’s cryptic statements on creativity, and his idiosyncratic behaviour during the solo concerts. -

Doctor of Philosophy

KWAME NKRUMAH UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY KUMASI, GHANA Optimizing Vermitechnology for the Treatment of Blackwater: A Case of the Biofil Toilet Technology By OWUSU, Peter Antwi (BSc. Civil Eng., MSc. Water supply and Environmental Sanitation) A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Civil Engineering, College of Engineering in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy October, 2017 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work towards the PhD and that, to the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published by another person nor material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree of any university, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. OWUSU Peter Antwi ………………….. ……………. (PG 8372212) Signature Date Certified by: Dr. Richard Buamah …………………. .................... (Supervisor) Signature Date Dr. Helen M. K. Essandoh (Mrs) …………………. .................... (Supervisor) Signature Date Prof. Esi Awuah (Mrs) …………………. .................... (Supervisor) Signature Date Prof. Samuel Odai …………………. .................... (Head of Department) Signature Date i ABSTRACT Human excreta management in urban settings is becoming a serious public health burden. This thesis used a vermi-based treatment system; “Biofil Toilet Technology (BTT)” for the treatment of faecal matter. The BTT has an average household size of 0.65 cum; a granite porous filter composite for solid-liquid separation; coconut fibre as a bulking material and worms “Eudrilus eugeniae” -

USER GUIDE Electronic Bidet Seat

USER GUIDE Electronic Bidet Seat BEYOND TECHNOLOGY Powered by TOTO Functions Functions Rearwash Cleanse Rear soft cleanse Ladywash Nozzle position adjustment Water volume Basic Changing the washing Functions Oscillating comfort wash method Pulsating wash User setting Drying Air dryer Changing the temperature Temperature adjustment Sanitary Removing odors Functions $LUSXUL¿HU Remote controlled seat and lid Opening and closing Automatic open / close (seat and lid) Convenient Lighting up Night light Functions Heating the toilet seat Heated seat Timer energy saver Energy saving Auto energy saver Removable toilet lid Maintenance Nozzle cleaning 2 Table of Contents Safety Precautions .................... 4 Operational Precautions ........... 10 Parts Names ............................. 12 Preparation ............................... 14 Introduction Model name Basic Operations ...................... 16 Part No. Automatic Functions ................. 20 $LUSXUL¿HUDXWRRSHQFORVH night light ............................... 20 Temperature adjustment ........... 22 Operation Energy Saver Features ............. 24 Power Plug / Main unit .............. 28 Gap between the Main Unit and the Toilet Lid ...................... 30 Deodorizing Filter ..................... 31 Nozzle cleaning ........................ 32 :DWHU¿OWHUGUDLQYDOYH 33 Maintenance Changing Settings .................... 34 What to Do?............................... 46 Ɣ,I\RXFDQQRWRSHUDWHZLWK the remote control .................. 46 Ɣ)UHH]H'DPDJH3UHYHQWLRQ 47 Ɣ/RQJ3HULRGVRI'LVXVH 48 Troubleshooting -

Renault Cla Ssic

RENAULT CLASSICCLASSIC LES CAHIERS CAHIERS PASSION PASSION HS “ LESLES RENAULT, RENAULT, MA FAMILLE MA FAMILLE ET MOI ” ET MOI ” Témoignage d’une jeune mère de famille (par Marion Rannou-PEHUN) 01 DAD’S AMAZING RENAULT 16 01 L’EXTRAORDINAIRE RENAULT 16 DE PAPA possessed until then. This was the Elle était grise. Grise ardoise. Les J’avais dix ou onze ans. C’était la Chaque nouvelle voiture était confort des banquettes, découvrir beautiful car that Dad would take to vitres étaient électriques à l’avant. voiture de mon père : une RENAULT vécue comme une fête. D’abord, les options, admirer la vue depuis le come get me from middle school at Une condamnation centralisée 16... Une RENAULT 16 TX. nous nous félicitions du choix de la tableau de bord et nous imprégner lunchtime. Our discussions were pouvait fermer toutes les portes couleur, objet de tant de discussions de l’odeur unique du cuir et des fairly brief: it was time to watch the Lorsque je pense aux voitures qui plastiques neufs. Ce cérémonial news. I can see the parking lot d’un seul tour de clef et comble m’ont accompagnées, c’est cette familiales, puis avec un soin qui fut très marqué lorsque la nouvelle perfectly, in front of school where du confort, elle était dotée d’une image-là qui tout de suite, s’imposé ne durerait malheureusement pas RENAULT 16 emprunta pour la he was waiting for me, always on climatisation. L’intérieur était d’un et puis le film s’enclenche et une très longtemps, nous montions à première fois l’allée de la maison, et time. -

Roval™ Surface Mounted Seat Cover Dispenser

AMERICAN SPECIALTIES, INC. MODEL №: 20477-SM 441 Saw Mill River Road, NY 10701 (914) 476-9000 www.americanspecialties.com ISSUED: 08/09 REVISED: ROVAL™ SURFACE MOUNTED SEAT COVER DISPENSER 3 15- 4" [400] 3 2- 8" [60] TOP VIEW MOUNTING HOLES 5 12- 8" [320] 1 3- 2" [89] 1 3- 8" [80] 11" [280] 11 1 8- 16" [220] 7- 2" NOTE: [191] ALL DIMS INCH [MM] FRONT VIEW SPECIFICATION Roval™ Collection Surface Mounted Seat Cover Dispenser shall hold and dispense 250 standard single or half-fold paper toilet seat covers contained in supply box. Cabinet full panel shall be drawn seamless and shall have bowed front face and gently radiused edges to provide added strength and complimentary appearance for modern wash- room aesthetics. Unit shall be 22 gauge type 304 stainless steel alloy 18-8 and all exposed surfaces shall have satin finish protected during shipment with PVC film that is easily removable after installation. Cover dispensing slot shall have a fully deburred flat edge for snag-free dispensing and user safety. Structural assembly of cover and mounting bar components shall be of welded construction with no visible spot-welded seams or fasteners. Roval™ Collection Surface Mounted Toilet Seat Cover Dispenser shall be Model № 20477SM of American Specialties, Inc. 441 Saw Mill River Road Yonkers, New York 10701-4913 INSTALLATION Mount unit on wall or partition surface using two (2) № 10 x 1-1/4" (32) self-tapping flat head screws (by others). Mounting holes are clearly accessible through dispenser slot for installation and concealed behind dispenser box for vandal resistant locking after dispense product is loaded. -

Wild Swans Three Daughters of China Jung Chang

Wild Swans Three daughters of China Jung Chang Flamingo An Imprint of HarperCollins Publish 77-85 Fulham Palace Road, Hammersmith, London W6 8JB Special overseas edition 1992 This paperback edition 1993 59 58 57 56 55 54 53 First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publish 1991 Copyright © Glohalflair Ltd 1991 ISBN 0 00 637492 1 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St. Ives plc All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. To my grandmother and my father who did not live to see this book AUTHOR'S NOTE My name "Jung' is pronounced "Yung." The names of members of my family and public figures are real, and are spelled in the way by which they are usually known. Other personal names are disguised. Two difficult phonetic symbols: X and Q are pronounced, respectively, as shand chIn order to describe their functions accurately, I have translated the names of some Chinese organizations differently from the Chinese official versions. I use 'the Department of Public Affairs' rather than 'the Department of Propaganda' for xuan-chuan-bu, and 'the Cultural Revolution Authority' rather than 'the Cultural Revolution Group' for zhong-yang- well-ge. -

Song List by Artist

Song List by Artist Artist Song Name 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT EAT FOR TWO WHAT'S THE MATTER HERE 10CC RUBBER BULLETS THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 ANYWHERE [FEAT LIL'Z] CUPID PEACHES AND CREAM 112 FEAT SUPER CAT NA NA NA NA 112 FEAT. BEANIE SIGEL,LUDACRIS DANCE WITH ME/PEACHES AND CREAM 12TH MAN MARVELLOUS [FEAT MCG HAMMER] 1927 COMPULSORY HERO 2 BROTHERS ON THE 4TH FLOOR COME TAKE MY HAND NEVER ALONE 2 COW BOYS EVERYBODY GONFI GONE 2 HEADS OUT OF THE CITY 2 LIVE CREW LING ME SO HORNY WIGGLE IT 2 PAC ALL ABOUT U BRENDA’S GOT A BABY Page 1 of 366 Song List by Artist Artist Song Name HEARTZ OF MEN HOW LONG WILL THEY MOURN TO ME? I AIN’T MAD AT CHA PICTURE ME ROLLIN’ TO LIVE & DIE IN L.A. TOSS IT UP TROUBLESOME 96’ 2 UNLIMITED LET THE BEAT CONTROL YOUR BODY LETS GET READY TO RUMBLE REMIX NO LIMIT TRIBAL DANCE 2PAC DO FOR LOVE HOW DO YOU WANT IT KEEP YA HEAD UP OLD SCHOOL SMILE [AND SCARFACE] THUGZ MANSION 3 AMIGOS 25 MILES 2001 3 DOORS DOWN BE LIKE THAT WHEN IM GONE 3 JAYS FEELING IT TOO LOVE CRAZY EXTENDED VOCAL MIX 30 SECONDS TO MARS FROM YESTERDAY 33HZ (HONEY PLEASER/BASS TONE) 38 SPECIAL BACK TO PARADISE BACK WHERE YOU BELONG Page 2 of 366 Song List by Artist Artist Song Name BOYS ARE BACK IN TOWN, THE CAUGHT UP IN YOU HOLD ON LOOSELY IF I'D BEEN THE ONE LIKE NO OTHER NIGHT LOVE DON'T COME EASY SECOND CHANCE TEACHER TEACHER YOU KEEP RUNNIN' AWAY 4 STRINGS TAKE ME AWAY 88 4:00 PM SUKIYAKI 411 DUMB ON MY KNEES [FEAT GHOSTFACE KILLAH] 50 CENT 21 QUESTIONS [FEAT NATE DOGG] A BALTIMORE LOVE THING BUILD YOU UP CANDY SHOP (INSTRUMENTAL) CANDY SHOP (VIDEO) CANDY SHOP [FEAT OLIVIA] GET IN MY CAR GOD GAVE ME STYLE GUNZ COME OUT I DON’T NEED ‘EM I’M SUPPOSED TO DIE TONIGHT IF I CAN’T IN DA CLUB IN MY HOOD JUST A LIL BIT MY TOY SOLDIER ON FIRE Page 3 of 366 Song List by Artist Artist Song Name OUTTA CONTROL PIGGY BANK PLACES TO GO POSITION OF POWER RYDER MUSIC SKI MASK WAY SO AMAZING THIS IS 50 WANKSTA 50 CENT FEAT. -

Linear Film 114 - Online Space 118

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details !1 THIS IS NOT US: Performance, Relationships and Shame in Documentary Filmmaking Daisy Asquith PhD CREATIVE & CRITICAL PRACTICE University of Sussex, June 2018 WORD COUNT: 40,072 PRACTICE ONLINE: https://daisy-asquith-xdrf.squarespace.com/home/ !2 Summary This thesis investigates performance, identity, representation and shame in documentary flmmaking. Identities that are performed and mediated through a relationship between flmmaker and participant are examined with detailed reference to two decades of my own practice. A refexive, feminist approach engages my own flms - and the relationships that produced them - in analysis of the ethical potholes and emotional challenges in representing others on TV. The trigger for this research was the furiously angry reaction of the One Direction fandom to my representation of them in Crazy About One Direction (Channel 4, 2013). This offered an opportunity to investigate the potential for shame in documentary; a loud and clear case study of flmed participants using social media to contest their image on screen. -

Designing the Next Generation of Sanitation Businesses

DESIGNING THE NEXT GENERATION OF SANITATION BUSINESSES A REPORT BY HYSTRA FOR THE TOILET BOARD COALITION - SEPTEMBER 2014 SPONSORED BY Authors Contributors Jessica Graf, Hystra Network Partner Heiko Gebauer, Eawag Olivier Kayser, Hystra Managing Director Lucie Klarsfeld, Hystra Project Manager Simon Brossard, Hystra Consultant Mathilde Moine, Hystra Junior Consultant To download this Report, visit www.hystra.com For more information on this project, please contact: [email protected] About Hystra Hystra is a global consulting firm that works with business and social sector pioneers to design and implement hybrid strategies, i.e. innovative market-like approaches that are economically sustainable, scalable and eradicate social and environmental problems, and combine the insights and resources of for-profit and not-for-profit sectors. For more information, visit www.hystra.com ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors of this Report would like to thank the Sponsors that made this work possible. Integrating their different perspectives has been critical in shaping meaningful recommendations for the sector. We also want to thank the social entrepreneurs who shared Nageshwara Charitable Trust (NCT), Sanishop India, their innovative work, and the experts who contributed eKutir: Rita Bhoyar, Mukund Dhok, HMB Murthy insights over the course of this study. Your support and (Nageshwara Charitable Trust), R. Subramaniam Iyer, commitment are deeply appreciated. Sundeep Vira (WTO), KC Mishra (eKutir), Tripti Naswa (Sattva) In addition, the authors would like to acknowledge that the SOIL/Re.source: Sasha Kramer, Leah Page work presented in the Report builds on the research work WaterSHED: Phav Daroath, Aun Hengly, Lyn Mclennan, undertaken by the Toilet Board Coalition, a global business- Geoff Revell led alliance that aims to promote market-based solutions X-Runner: Jessica Altenburger, Isabel Medem to sanitation and bring them to scale.