Phd Thesis Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phd Thesis Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film And

PhD Thesis Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies NEGOTIATIONS OF IDENTITY IN MINORITY LANGUAGE MEDIA FROM SILENCE TO THE WORD Supervisors: Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones Prof. Tom O’Malley Thesis presented to attain the title of PhD by: Enrique Uribe-Jongbloed January 17, 2013 Statement of originality I hereby ensure that the content of this thesis is original and all information used in it from sources, other than my own ideas, has been credited according to the referencing style of the APA 6th Edition. Signature: Date: I Statement of Public Access I hereby state that this thesis may be made available for inter-library loans or photocopying (subject to the law of copyright), and that the title and summary may be made available to outside organisations. Signature: Date: II Summary The present research explores the growing field of studies of Minority Language Media by focusing on two case studies, Wales and Colombia. The research seeks to answer the question of how the complex, hybrid identity of media producers negotiate their various identity allegiances in the preparation and broadcast of output for Minority Language Media. The research process takes an interpretative and qualitative stance to interviews with producers and participant observation of the production process, to determine the impact of the different negotiations of identity upon linguistic output. This analysis allows for a comparative discussion which provides new elements for the study of Minority Language Media from manifold perspectives: it evidences the impact of certain identifications on the linguistic output of media, it shows the various stances that may be adopted in regards to the purpose and interest of Minority Language Media, and it provides a set of examples which enable a discussion about the development of the field of studies beyond the European remit from whence it stems. -

Black Box Approaches to Genealogical Classification and Their Shortcomings Jelena Prokić and Steven Moran

Black box approaches to genealogical classification and their shortcomings Jelena Prokić and Steven Moran 1. Introduction In the past 20 years, the application of quantitative methods in historical lin- guistics has received a lot of attention. Traditional historical linguistics relies on the comparative method in order to determine the genealogical related- ness of languages. More recent quantitative approaches attempt to automate this process, either by developing computational tools that complement the comparative method (Steiner et al. 2010) or by applying fully automatized methods that take into account very limited or no linguistic knowledge, e.g. the Levenshtein approach. The Levenshtein method has been extensively used in dialectometry to measure the distances between various dialects (Kessler 1995; Heeringa 2004; Nerbonne 1996). It has also been frequently used to analyze the relatedness between languages, such as Indo-European (Serva and Petroni 2008; Blanchard et al. 2010), Austronesian (Petroni and Serva 2008), and a very large sample of 3002 languages (Holman 2010). In this paper we will examine the performance of the Levenshtein distance against n-gram models and a zipping approach by applying these methods to the same set of language data. The success of the Levenshtein method is typically evaluated by visu- ally inspecting and comparing the obtained genealogical divisions against already well-established groupings found in the linguistics literature. It has been shown that the Levenshtein method is successful in recovering main languages groups, which for example in the case of Indo-European language family, means that it is able to correctly classify languages into Germanic, Slavic or Romance groups. -

ARAWAK LANGUAGES” by Alexandra Y

OXFORD BIBLIOGRAPHIES IN LINGUISTICS “ARAWAK LANGUAGES” by Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald © Oxford University Press Not for distribution. For permissions, please email [email protected]. xx Introduction General Overviews Monographs and Dissertations Articles and Book Chapters North Arawak Languages Monographs and Dissertations Articles and Book Chapters Reference Works Grammatical and Lexical Studies Monographs and Dissertations Articles and Book Chapters Specific Issues in the Grammar of North Arawak Languages Mixed Arawak-Carib Language and the Emergence of Island Carib Language Contact and the Effects of Language Obsolescence Dictionaries of North Arawak Languages Pre-andine Arawak Languages Campa Languages Monographs and Dissertations Articles and Book Chapters Amuesha Chamicuro Piro and Iñapari Apurina Arawak Languages of the Xingu Indigenous Park Arawak Languages of Areas near Xingu South Arawak Languages Arawak Languages of Bolivia Introduction The Arawak family is the largest in South America, with about forty extant languages. Arawak languages are spoken in lowland Amazonia and beyond, covering French Guiana, Suriname, Guiana, Venezuela, Colombia, Peru, Brazil, and Bolivia, and formerly in Paraguay and Argentina. Wayuunaiki (or Guajiro), spoken in the region of the Guajiro peninsula in Venezuela and Colombia, is the largest language of the family. Garifuna is the only Arawak language spoken in Belize, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Guatemala in Central America. Groups of Arawak speakers must have migrated from the Caribbean coast to the Antilles a few hundred years before the European conquest. At least several dozen Arawak languages have become extinct since the European conquest. The highest number of recorded Arawak languages is centered in the region between the Rio Negro and the Orinoco. -

Guajiro) Andres M

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Linguistics ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Summer 7-18-2018 The aV riable Expression of Transitive Subject and Possesor in Wayuunaiki (Guajiro) Andres M. Sabogal Universitiy of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ling_etds Part of the Caribbean Languages and Societies Commons, Discourse and Text Linguistics Commons, Language Description and Documentation Commons, Morphology Commons, Semantics and Pragmatics Commons, and the Syntax Commons Recommended Citation Sabogal, Andres M.. "The aV riable Expression of Transitive Subject and Possesor in Wayuunaiki (Guajiro)." (2018). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ling_etds/59 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Linguistics ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Andrés M. Sabogal Candidate Linguistics Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. Melissa Axelrod , Chairperson Dr. Rosa Vallejos Yopán Dr. José Ramón Álvarez Dr. Alexandra Yurievna Aikhenvald ii The Variable Expression of Transitive Subject and Possessor in Wayuunaiki (Guajiro) BY Andrés M. Sabogal Valencia B.A., Spanish, Sonoma State University, 2008 M.A. Latin American Studies, The University of New Mexico, 2010 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Ph.D. in Linguistics The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico July 2018 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without my immense support network. -

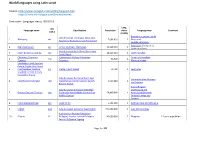

World Languages Using Latin Script

World languages using Latin script Source: http://www.omniglot.com/writing/langalph.htm https://www.ethnologue.com/browse/names Sort order : Language status, ISO 639-3 Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Botswana, Lesotho, South Indo-European, Germanic, West, Low 1. Afrikaans, afr 7,096,810 1 Africa and Saxon-Low Franconian, Low Franconian SwazilandNamibia Azerbaijan,Georgia,Iraq 2. Azeri,Azerbaijani azj Turkic, Southern, Azerbaijani 24,226,940 1 Jordan and Syria Indo-European Balto-Slavic Slavic West 3. Czech Bohemian Cestina ces 10,619,340 1 Czech Republic Czech-Slovak Chamorro,Chamorru Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian Guam and Northern 4. cha 94,700 1 Tjamoro Chamorro Mariana Islands Seychelles Creole,Seselwa Creole, Creole, Ilois, Kreol, 5. Kreol Seselwa, Seselwa, crs Creole, French based 72,700 1 Seychelles Seychelles Creole French, Seychellois Creole Indo-European Germanic North East Denmark Finland Norway 6. DanishDansk Rigsdansk dan Scandinavian Danish-Swedish Danish- 5,520,860 1 and Sweden Riksmal Danish AustriaBelgium Indo-European Germanic West High Luxembourg and 7. German Deutsch Tedesco deu German German Middle German East 69,800,000 1 NetherlandsDenmark Middle German Finland Norway and Sweden 8. Estonianestieesti keel ekk Uralic Finnic 1,132,500 1 Estonia Latvia and Lithuania 9. English eng Indo-European Germanic West English 341,000,000 1 over 140 countries Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian 10. Filipino fil Philippine Greater Central Philippine 45,000,000 1 Filippines L2 users population Central Philippine Tagalog Page 1 of 48 World languages using Latin script Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Denmark Finland Norway 11. -

Computational Phylogenetics and the Classification of South American Languages

Computational Phylogenetics and the Classification of South American Languages Abstract In recent years, South Americanist linguists have embraced computational phylogenetic methods to resolve the numerous outstanding questions about the genealogical relationships among the languages of the continent. We provide a critical review of the methods and language classification results that have accumulated thus far, emphasizing the superiority of character-based methods over distance-based ones, and the importance of developing adequate comparative datasets for producing well-resolved classifications. Key words: computational phylogenetics, language classification, South American languages 1. Introduction South America presents one of the greatest challenges to linguists seeking to unravel the genealogical relationships among the world's languages, exhibiting one of the highest rates of linguistic diversity of the world's major regions (Epps 2009, Epps and Michael 2017). The comparative study of South American languages is quite uneven, however, with most language families lacking classifications based on the comparative method, and the internal organization of even major families being uncertain in important respects. Given the magnitude of the challenge facing South American linguists, it is perhaps unsurprising that they have embraced the promise of computational phylogenetic methods for clarifying genealogical relationships. The goal of this paper is to provide a state-of-the-art overview of this active research area, focusing on the strengths and weaknesses of the various methods employed, and their contributions to the classification of South American languages. As we show, computational phylogenetic methods are already yielding important results regarding the classification of South American languages, and the prospects for future advances are promising. -

An Ethnographic Account of Language Documentation Among the Kurripako of Venezuela

An Ethnographic Account of Language Documentation Among the Kurripako of Venezuela Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Granadillo, Tania Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 30/09/2021 21:40:04 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/195916 AN ETHNOGRAPHIC ACCOUNT OF LANGUAGE DOCUMENTATION AMONG THE KURRIPAKO OF VENEZUELA By Tania Granadillo Copyright © Tania Granadillo 2006 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENTS OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND LINGUISTICS In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 6 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Tania Granadillo entitled An Ethnographic Account of Language Documentation among the Kurripako of Venezuela and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________________________________________ Date: April 7 2006 Jane Hill _______________________________________________________________________ Date: April 7 2006 Michael Hammond _______________________________________________________________________ Date: April 7 2006 Heidi Harley _______________________________________________________________________ Date: April 7 2006 Ofelia Zepeda Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

The Languages of the Andes

THE LANGUAGES OF THE ANDES The Andean and Pacific regions of South America are home to a remark- able variety of languages and language families, with a range of typologi- cal differences. This linguistic diversity results from a complex historical background, comprising periods of greater communication between dif- ferent peoples and languages, and periods of fragmentation and individual development. The Languages of the Andes is the first book in English to document in a single volume the indigenous languages spoken and for- merly spoken in this linguistically rich region, as well as in adjacent areas. Grouping the languages into different cultural spheres, it describes their characteristics in terms of language typology, language contact, and the social perspectives of present-day languages. The authors provide both historical and contemporary information, and illustrate the languages with detailed grammatical sketches. Written in a clear and accessible style, this book will be a valuable source for students and scholars of linguistics and anthropology alike. . is Professor of Amerindian Languages and Cul- tures at Leiden University. He has travelled widely in South America and has conducted fieldwork in Peru on different varieties of Quechua and minor languages of the area. He has also worked on the historical- comparative reconstruction of South American languages, and since 1991 has been involved in international activities addressing the issue of lan- guage endangerment. His previously published books include Tarma Quechua (1977) and Het Boek van Huarochir´ı (1988). . is Professor of Linguistics at the University of Nijmegen. He has travelled widely in the Caribbean and the Andes, and was previously Professor of Sociolinguistics and Creole Studies at the Uni- versity of Amsterdam and Professor of Linguistics and Latin American Studies at Leiden University. -

Indigenous Water Governance in the Anthropocene: Non- Conventional Hydrosocial Relations Among the Wayuu of the Guajira Peninsula in Northern Colombia

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-23-2020 Indigenous Water Governance in the Anthropocene: Non- Conventional Hydrosocial Relations Among the Wayuu of the Guajira Peninsula in Northern Colombia David A. Robles Florida International University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Robles, David A., "Indigenous Water Governance in the Anthropocene: Non-Conventional Hydrosocial Relations Among the Wayuu of the Guajira Peninsula in Northern Colombia" (2020). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 4416. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/4416 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida INDIGENOUS WATER GOVERNANCE IN THE ANTHROPOCENE: NON- CONVENTIONAL HYDROSOCIAL RELATIONS AMONG THE WAYUU OF THE GUAJIRA PENINSULA IN NORTHERN COLOMBIA A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in GLOBAL AND SOCIOCULTURAL STUDIES by David Robles 2020 To: Dean John F. Stack, Jr. Steven J. Green School of International and Public Affairs This dissertation, written by David Robles, and entitled Indigenous Water Governance in the Anthropocene: Non-Conventional Hydrosocial Relations Among the Wayuu of the Guajira Peninsula in Northern Colombia, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. -

The Poetics of Indigenous Radio in Colombia Clemencia Rodríguez1 UNIVERSITY of OKLAHOMA Jeanine El Gazi MINISTRY of CULTURE,COLOMBIA

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SHAREOK repository The poetics of indigenous radio in Colombia Clemencia Rodríguez1 UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA Jeanine El Gazi MINISTRY OF CULTURE,COLOMBIA In 2002, 14 indigenous radio stations began operating in Colombia, reaching 78.6 percent of the national indigenous population (Ministerio de Cultura, 2002: 10). In this article we intend to shed light on the complex relationships and interactions behind Colombian indigenous radio stations. Colombian indigenous radio can only be understood as a product of intricate relation- ships between indigenous social movements, armed conflict, the state and media activism. In the following pages we will explain how Colombian indigenous peoples articulate a strong and highly developed response toward the presence of media technologies among their communities. This response is framed by new legislative frameworks made possible by the constitutional reform of 1991, by indigenous peoples’ critique of Colombian mainstream media and, finally, by discussions among indigenous peoples about the adop- tion of radio – what we call a poetics of radio. The data for this article comes mostly from unpublished documents, archives and recordings kept at the Ministry of Culture (Unidad de Radio/Office of Radio). The Colombian indigenous population is 708,000; despite the fact that they constitute less than 2 percent of the national population and include more than 80 different ethnic groups with their corresponding languages, widely scat- tered across a rough terrain, indigenous people have both captured and repre- sented some of the most significant notions in Colombia’s modern political arena.2 Colombian indigenous people have played a remarkable role in the political consciousness and imaginaries in contemporary Colombia. -

Genomic and Climatic Effects on Human Crania from South America: a Comparative

Genomic and Climatic Effects on Human Crania from South America: A Comparative Microevolutionary Approach Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Brianne C. Herrera, M.A. Graduate Program in Anthropology The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee Mark Hubbe, Advisor Clark Spencer Larsen Debbie Guatelli-Steinberg Jeffrey McKee Copyrighted by Brianne C. Herrera 2019 Abstract Cranial morphology has been widely used to estimate phylogenetic relationships among and between populations. When compared against genetic data, however, discrepancies arise in terms of population affinity and effects of microevolutionary processes. These discrepancies are particularly apparent in studies of the human dispersion to the New World. Despite the apparent discrepancies, research has thus far been limited in scope when analyzing the relationship between the cranial morphology and genetic markers. This dissertation aimed to fill this void in research by providing a necessary broad comparative approach, incorporating 3D morphological and climate data, mtDNA, and Y-chromosome DNA from South America. The combination of these data types allows for a more complete comparative analysis of microevolutionary processes. Correlations between these different data types allow for the assessment their relatedness, while quantitatively testing microevolutionary models permit determining the congruence of these different data types. I asked the following research questions: 1) how consistent are the patterns of population affinity when comparing different regions of the crania to each type of DNA for populations in South America? 2) If they are not consistent, why not? How are different evolutionary forces affecting the affinities between them? Collectively, both the cranial and genetic data demonstrated patterns of isolation-by-distance when viewed from a continent-wide scale. -

Redalyc.Mitochondrial DNA Analysis Suggests a Chibchan Migration Into

Universitas Scientiarum ISSN: 0122-7483 [email protected] Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Colombia Noguera-Santamaría, María Claudia; Edlund Anderson, Carl; Uricoechea, Daniel; Durán, Clemencia; Briceño-Balcázar, Ignacio; Bernal Villegas, Jaime Mitochondrial DNA analysis suggests a Chibchan migration into Colombia Universitas Scientiarum, vol. 20, núm. 2, mayo-agosto, 2015, pp. 261-278 Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Bogotá, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=49935358008 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Univ. Sci. 2015, Vol. 20 (2): 261-278 doi: 10.11144/Javeriana.SC20-2.mdas Freely available on line original paper Mitochondrial DNA analysis suggests a Chibchan migration into Colombia María Claudia Noguera-Santamaría 1, 2, 5 , Carl Edlund Anderson 3, Daniel Uricoechea 2, Clemencia Durán 1, Ignacio Briceño-Balcázar 1, 2 , Jaime Bernal Villegas 1, 4 Abstract The characterization of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) allows the establishment of genetic structures and phylogenetic relationships in human populations, tracing lineages far back in time. We analysed samples of mtDNA from twenty (20) Native American populations (700 individuals) dispersed throughout Colombian territory. Samples were collected during 1989-1993 in the context of the program Expedición Humana (“Human Expedition”) and stored in the Biological Repository of the Institute of Human Genetics (IGH) at the Ponticia Universidad Javeriana (Bogotá, Colombia). Haplogroups were determined by analysis of RFLPs. Most frequent was haplogroup A, with 338 individuals (48.3%). Haplogroup A is also one of the most frequent haplogroups in Mesoamerica, and we interpret our nding as supporting models that propose Chibchan-speaking groups migrated to northern Colombia from Mesoamerica in prehistoric times.