The Role of Pollinator Preference in the Maintenance of Pollen Colour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anthidium Manicatum, an Invasive Bee, Excludes a Native Bumble Bee, Bombus Impatiens, from floral Resources

Biol Invasions https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-018-1889-7 (0123456789().,-volV)(0123456789().,-volV) ORIGINAL PAPER Anthidium manicatum, an invasive bee, excludes a native bumble bee, Bombus impatiens, from floral resources Kelsey K. Graham . Katherine Eaton . Isabel Obrien . Philip T. Starks Received: 15 April 2018 / Accepted: 21 November 2018 Ó Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2018 Abstract Anthidium manicatum is an invasive pol- response to A. manicatum presence. We found that B. linator reaching widespread distribution in North impatiens avoided foraging near A. manicatum in both America. Male A. manicatum aggressively defend years; but despite this resource exclusion, we found no floral territories, attacking heterospecific pollinators. evidence of fitness consequences for B. impatiens. Female A. manicatum are generalists, visiting many of These results suggest A. manicatum pose as significant the same plants as native pollinators. Because of A. resource competitors, but that B. impatiens are likely manicatum’s rapid range expansion, the territorial able to compensate for this resource loss by finding behavior of males, and the potential for female A. available resources elsewhere. manicatum to be significant resource competitors, invasive A. manicatum have been prioritized as a Keywords Exotic species Á Resource competition Á species of interest for impact assessment. But despite Interspecific competition Á Foraging behavior Á concerns, there have been no empirical studies inves- Pollination tigating the impact of A. manicatum on North Amer- ican pollinators. Therefore, across a two-year study, we monitored foraging behavior and fitness of the common eastern bumble bee (Bombus impatiens) in Introduction With increasing movement of goods and people Electronic supplementary material The online version of around the world, introduction of exotic species is this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-018-1889-7) con- increasing at an unprecedented rate (Ricciardi et al. -

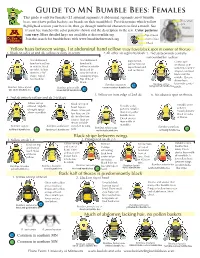

Guide to MN Bumble Bees: Females

Guide to MN Bumble Bees: Females This guide is only for females (12 antennal segments, 6 abdominal segments, most bumble Three small bees, most have pollen baskets, no beards on their mandibles). First determine which yellow eyes highlighted section your bee is in, then go through numbered characters to find a match. See if your bee matches the color patterns shown and the description in the text. Color patterns ® can vary. More detailed keys are available at discoverlife.org. Top of head Bee Front of face Squad Join the search for bumble bees with www.bumbleebeewatch.org Cheek Yellow hairs between wings, 1st abdominal band yellow (may have black spot in center of thorax) 1. Black on sides of 2nd ab, yellow or rusty in center 2.All other ab segments black 3. 2nd ab brownish centrally surrounded by yellow 2nd abdominal 2nd abdominal Light lemon Center spot band with yellow band with yellow hairs on on thorax with in middle, black yellow in middle top of head and sometimes faint V on sides. Yellow bordered by and on thorax. shaped extension often in a “W” rusty brown in a back from the shape. Top of swooping shape. middle. Queens head yellow. Top of head do not have black. Bombus impatiens Bombus affinis brownish central rusty patched bumble bee Bombus bimaculatus Bombus griseocollis common eastern bumble bee C patch. two-spotted bumble bee C brown-belted bumble bee C 5. Yellow on front edge of 2nd ab 6. No obvious spot on thorax. 4. 2nd ab entirely yellow and ab 3-6 black Yellow on top Black on top of Variable color of head. -

Bumble Bee Abundance in New York City Community Gardens: Implications for Urban Agriculture

Matteson and Langellotto: URBAN BUMBLE BEE ABUNDANCE Cities and the Environment 2009 Volume 2, Issue 1 Article 5 Bumble Bee Abundance in New York City Community Gardens: Implications for Urban Agriculture Kevin C. Matteson and Gail A. Langellotto Abstract A variety of crops are grown in New York City community gardens. Although the production of many crops benefits from pollination by bees, little is known about bee abundance in urban community gardens or which crops are specifically dependent on bee pollination. In 2005, we compiled a list of crop plants grown within 19 community gardens in New York City and classified these plants according to their dependence on bee pollination. In addition, using mark-recapture methods, we estimated the abundance of a potentially important pollinator within New York City urban gardens, the common eastern bumble bee (Bombus impatiens). This species is currently recognized as a valuable commercial pollinator of greenhouse crops. However, wild populations of B. impatiens are abundant throughout its range, including in New York City community gardens, where it is the most abundant native bee species present and where it has been observed visiting a variety of crop flowers. We conservatively counted 25 species of crop plants in 19 surveyed gardens. The literature suggests that 92% of these crops are dependent, to some degree, on bee pollination in order to set fruit or seed. Bombus impatiens workers were observed visiting flowers of 78% of these pollination-dependent crops. Estimates of the number of B. impatiens workers visiting individual gardens during the study period ranged from 3 to 15 bees per 100 m2 of total garden area and 6 to 29 bees per 100 m2 of garden floral area. -

Conserving Missouri's Wild and Managed Pollinators

Conserving Missouri’s Wild and Managed Pollinators At the heart of the pollination issue lies our bounty of foods such as peaches, Go to the bee, thou poet: strawberries, squash and apples. These and other foods requiring pollination have consider her ways and be wise. been staples in the human diet for centuries, and their pollinators have been highly — George Bernard Shaw revered since ancient times. From Egyptian hieroglyphics and Native American cave paintings to Greek mythology and English poetry, bees and butterflies have been a source of fascination and awe for millennia (Figure 1). Yet, over the past century, pollinator numbers have suffered declines. During this time, global development, a booming human population, and industrial agriculture brought about drastic landscape changes. These changes have resulted in greater losses of forage and nesting resources for pollinators than ever before seen. The ecosystem service of pollination, once taken for granted, is now potentially threatened as many pollinator species face declines in Missouri, the United States and many regions around the world. Pollinators are critically important for natural ecosystems and crop production. Through pollination, they perform roles essential to human welfare. Heightened public awareness of their services and of their declines over the past two decades has prompted action, but much remains to be done. This publication introduces issues regarding the conservation of pollinators in Missouri. It explores why pollinators are crucial, what major threats confront them, what conservation steps are being taken, and how you can help. It highlights bees over other pollinators as bees are the most important for both agricultural and natural pollination in Missouri. -

Nest Architecture, Life Cycle, and Natural

Nest architecture, life cycle, and natural enemies of the neotropical leafcutting bee Megachile (Moureapis) maculata (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) in a montane forest William de O. Sabino, Yasmine Antonini To cite this version: William de O. Sabino, Yasmine Antonini. Nest architecture, life cycle, and natural enemies of the neotropical leafcutting bee Megachile (Moureapis) maculata (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) in a mon- tane forest. Apidologie, Springer Verlag, 2017, 48 (4), pp.450-460. 10.1007/s13592-016-0488-9. hal- 01681897 HAL Id: hal-01681897 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01681897 Submitted on 11 Jan 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Apidologie (2017) 48:450–460 Original article * INRA, DIB and Springer-Verlag France, 2017 DOI: 10.1007/s13592-016-0488-9 Nest architecture, life cycle, and natural enemies of the neotropical leafcutting bee Megachile (Moureapis ) maculata (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) in a montane forest 1,2 1 William De O. SABINO , Yasmine A NTONINI 1Laboratório de Biodiversidade—Instituto de Ciências Exatas -

The Campanulaceae of Ohio1

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by KnowledgeBank at OSU 142 WIENS ET AL. Vol. 62 THE CAMPANULACEAE OF OHIO1 ROBERT W. CRUDEN2 Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Ohio State University, Columbus 10 In Ohio the family Campanulaceae is represented by three genera: Campanula, Lobelia, and Specularia; and eleven species, of which five are common throughout the state and two are quite limited in their distribution. Following the key to species each species is briefly described, and distribution, common names, chromosome numbers, if known, and other pertinent data are given. Chromosome numbers are those given in Darlington and Wylie (1956) and in the papers of Bowden (1959a, 1959b). Average time of flowering is indi- ^ontribution Nc. 666 of the Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, The Ohio State University. Research completed while a National Science Foundation Co-operative Fellow. 2Present address: Department of Botany, University of California, Berkeley 4, California. THE OHIO JOURNAL OF SCIENCE 62(3): 142, May, 1962. No. 3 CAMPANULACEAE OF OHIO 143 cated as well as the extreme flowering dates as determined from a study of her- barium material. The genera and species are arranged alphabetically. Distri- bution maps are included. A dot represents a collection of a particular species in a given county. No attempt has been made to indicate the general area of collection within the county, as a majority of herbarium specimens do not have this information. It should also be pointed out that many of the collections examined are forty or more years old and thus the distribution maps do not neces- sarily indicate present distribution. -

Complete Iowa Plant Species List

!PLANTCO FLORISTIC QUALITY ASSESSMENT TECHNIQUE: IOWA DATABASE This list has been modified from it's origional version which can be found on the following website: http://www.public.iastate.edu/~herbarium/Cofcons.xls IA CofC SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME PHYSIOGNOMY W Wet 9 Abies balsamea Balsam fir TREE FACW * ABUTILON THEOPHRASTI Buttonweed A-FORB 4 FACU- 4 Acalypha gracilens Slender three-seeded mercury A-FORB 5 UPL 3 Acalypha ostryifolia Three-seeded mercury A-FORB 5 UPL 6 Acalypha rhomboidea Three-seeded mercury A-FORB 3 FACU 0 Acalypha virginica Three-seeded mercury A-FORB 3 FACU * ACER GINNALA Amur maple TREE 5 UPL 0 Acer negundo Box elder TREE -2 FACW- 5 Acer nigrum Black maple TREE 5 UPL * Acer rubrum Red maple TREE 0 FAC 1 Acer saccharinum Silver maple TREE -3 FACW 5 Acer saccharum Sugar maple TREE 3 FACU 10 Acer spicatum Mountain maple TREE FACU* 0 Achillea millefolium lanulosa Western yarrow P-FORB 3 FACU 10 Aconitum noveboracense Northern wild monkshood P-FORB 8 Acorus calamus Sweetflag P-FORB -5 OBL 7 Actaea pachypoda White baneberry P-FORB 5 UPL 7 Actaea rubra Red baneberry P-FORB 5 UPL 7 Adiantum pedatum Northern maidenhair fern FERN 1 FAC- * ADLUMIA FUNGOSA Allegheny vine B-FORB 5 UPL 10 Adoxa moschatellina Moschatel P-FORB 0 FAC * AEGILOPS CYLINDRICA Goat grass A-GRASS 5 UPL 4 Aesculus glabra Ohio buckeye TREE -1 FAC+ * AESCULUS HIPPOCASTANUM Horse chestnut TREE 5 UPL 10 Agalinis aspera Rough false foxglove A-FORB 5 UPL 10 Agalinis gattingeri Round-stemmed false foxglove A-FORB 5 UPL 8 Agalinis paupercula False foxglove -

Bombus Impatiens, Common Eastern Bumblebee

Bombus impatiens, Common Eastern Bumble Bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) Christopher J. Fellows, Forest Huval, T.E. Reagan and Chris Carlton Description The common eastern bumble bee, Bombus impatiens, is an important native pollinator found in the eastern United States and southern Canada. Adult bees are covered with short, even hairs across their bodies. They are mostly black with a yellow thorax (middle section) and an additional yellow stripe at the base of the abdomen. As with other social insects, the different forms, or castes, of B. impatiens vary in size. Worker bumble bees measure from 1/3 to 2/3 of an inch in length (8.5-16 mm), while drones measure ½ to ¾ of an inch (12 to 18 mm). Queen bumble bees are the largest members of the three castes, measuring between 1/3 of an inch to 1 inch (17 and 23 mm) in length. Larvae are rarely seen and are enclosed with the nest brood cells for the duration of their A common eastern bumble bee resting on a flower. Note development. They are pale, legless grubs around 1 inch the yellow patch of hairs on the forward portion of the thorax (David Cappaert, Bugwood.org). (25 mm) in length. At least six additional species of bumble bees have been construction. Within the hollow fiber ball, the queen documented in Louisiana, with another two species possibly deposits a lump of nectar-moistened pollen. The queens present but not confirmed. Identifications are mainly based also construct honey pots near the nest entrance using on the patterns of coloration of the body hairs, but these the secretions of her wax glands. -

Creating Economically and Ecologically Sustainable Pollinator Habitat District 2 Demonstration Research Project Summary Updated for Site Visit in April 2019

Creating Economically and Ecologically Sustainable Pollinator Habitat District 2 Demonstration Research Project Summary Updated for Site Visit in April 2019 The PIs are most appreciative for identification assistance provided by: Arian Farid and Alan R. Franck, Director and former Director, resp., University of South Florida Herbarium, Tampa, FL; Edwin Bridges, Botanical and Ecological Consultant; Floyd Griffith, Botanist; and Eugene Wofford, Director, University of Tennessee Herbarium, Knoxville, TN Investigators Rick Johnstone and Robin Haggie (IVM Partners, 501-C-3 non-profit; http://www.ivmpartners.org/); Larry Porter and John Nettles (ret.), District 2 Wildflower Coordinator; Jeff Norcini, FDOT State Wildflower Specialist Cooperator Rick Owen (Imperiled Butterflies of Florida Work Group – North) Objective Evaluate a cost-effective strategy for creating habitat for pollinators/beneficial insects in the ROW beyond the back-slope. Rationale • Will aid FDOT in developing a strategy to create pollinator habitat per the federal BEE Act and FDOT’s Wildflower Program • Will demonstrate that FDOT can simultaneously • Create sustainable pollinator habitat in an economical and ecological manner • Reduce mowing costs • Part of national effort coordinated by IVM Partners, who has • Established or will establish similar projects on roadside or utility ROWS in Alabama, Arkansas, Maryland, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Idaho, Montana, Virginia, West Virginia, and Tennessee; studies previously conducted in Arizona, Delaware, Michigan, and New Jersey • Developed partnerships with US Fish & Wildlife Service, Army Corps of Engineers, US Geological Survey, New Jersey Institute of Technology, Rutgers University, Chesapeake Bay Foundation, Chesapeake Wildlife Heritage, The Navajo Nation, The Wildlife Habitat Council, The Pollinator Partnership, Progressive Solutions, Bayer Crop Sciences, Universities of Maryland, Ohio, West Virginia, and the EPA. -

Bumble Bees Are Essential

Prepared by the Bombus Task Force of the North American Pollinator Protection Campaign (NAPPC) Photo Sheila Colla Rusty-patched bumble bee, Bombus affi nis Declining North American Bumble Bees Photo David Inouye Western bumble bee, Bombus occidentalis Bumble Bees Helping Photo James Strange are Pollinators Essential Thrive Franklin bumble bee, Bombus franklini Bumble Bee Facts Photo Leif Richardson Globally, there are about 250 described species Some bumble bee are known to rob fl owers of bumble bees. They are found primarily in the of their nectar. Nectar robbing occurs when temperate zones of North and South America, a bee extracts nectar from a fl ower without and Eurasia. coming into contact with its reproductive Yellow-banded bumble bee, Bumble bees are documented to pollinate parts (i.e. anthers and/or stigma), usually Bombus terricola many important food crops. They are also more by biting a hole at the base of the fl ower. Photo Ron Hemberger effective than honey bees at pollinating crops Bumble bees are effective buzz pollinators grown in greenhouses. of several economically important plants in When most insects are inactive due to cold the family Solanaceae such as tomato, bell temperatures bumble bees are able to fl y by pepper and eggplant. In buzz pollination warming their fl ight muscles by shivering, bees extract pollen from a fl ower by American bumble bee, enabling them to raise their body temperature vibrating against the fl ower’s anthers, Bombus pensylvanicus as necessary for fl ight. making an audible buzzing noise. Instead of starting their own colonies, some Currently, the Common Eastern bumble bee bumble bee species have evolved to take over (Bombus impatiens) is the only species being another species’ colony to rear their young. -

How Does Genome Size Affect the Evolution of Pollen Tube Growth Rate, a Haploid Performance Trait?

Manuscript bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/462663; this version postedClick April here18, 2019. to The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv aaccess/download;Manuscript;PTGR.genome.evolution.15April20 license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Effects of genome size on pollen performance 2 3 4 5 How does genome size affect the evolution of pollen tube growth rate, a haploid 6 performance trait? 7 8 9 10 11 John B. Reese1,2 and Joseph H. Williams2 12 Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 13 37996, U.S.A. 14 15 16 17 1Author for correspondence: 18 John B. Reese 19 Tel: 865 974 9371 20 Email: [email protected] 21 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/462663; this version posted April 18, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 22 ABSTRACT 23 Premise of the Study – Male gametophytes of most seed plants deliver sperm to eggs via a 24 pollen tube. Pollen tube growth rates (PTGRs) of angiosperms are exceptionally rapid, a pattern 25 attributed to more effective haploid selection under stronger pollen competition. Paradoxically, 26 whole genome duplication (WGD) has been common in angiosperms but rare in gymnosperms. -

NATIVE POLLINATORS Who Are They and Are They Important?

NATIVE POLLINATORS Who are they and are they important? Compiled by Jim Revell, Bedford Extension Master Gardener Reproduction – the goal One goal of all living organisms, including plants, is to create offspring for the next generation. One method for plants to accomplish this is by producing seed. Pollen – a fine-to-coarse yellow dust or powder – “bears a plant’s male sex cells and is a vital link in the reproductive cycle.” USDA Forest Service • Pollination is usually an unplanned event due to an animal’s activity on a flower Pollination • It is calculated that one out of every three or four mouthfuls of food or drink “The act of transferring consumed is provided by pollinators pollen grains from the • male anther of a flower to More than 150 food crops in the U.S. depend on pollinators; this includes almost all fruit the female stigma.” and grain crops (see Handout, “List of USDA Forest Service Pollinated Foods” by Pollinator Partnership) • 80% or more of all plants worldwide Pollinator Methods: (including food crops) are pollinated by animals (biotic pollination) ABIOTIC: Without • Of the ≤20% abiotic method involvement of • organisms 98% are pollinated by wind • 2% are pollinated by water BIOTIC: Mediated by • ±200,000 species of animals around the animals world act as pollinators • Of the ±200,000 about 1,000 species are vertebrates (birds, bats, small mammals) Abiotic Pollinators: Wind | Water Left: Diagram of how Wind Pollination works; picture of windblown pollen from male cone of a Lodgepole Pine. Right: Diagram of how Water Pollination works; Seagrasses (marine angiosperms / flowering plants) have adapted to aquatic environments allowing for pollination, seed formation and germination in water.