Beatrice Rana Robert Schumann

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seattle Symphony October 2017 Encore

OCTOBER 2017 LUDOVIC MORLOT, MUSIC DIRECTOR BEATRICE RANA PLAYS PROKOFIEV GIDON KREMER SCHUMANN VIOLIN CONCERTO LOOKING AHEAD: MORLOT C O N D U C T S BERLIOZ CONTENTS My wealth. My priorities. My partner. You’ve spent your life accumulating wealth. And, no doubt, that wealth now takes many forms, sits in many places, and is managed by many advisors. Unfortunately, that kind of fragmentation creates gaps that can hold your wealth back from its full potential. The Private Bank can help. The Private Bank uses a proprietary approach called the LIFE Wealth Cycle SM to ind those gaps—and help you achieve what is important to you. To learn more, please visit unionbank.com/theprivatebank or contact: Lisa Roberts Managing Director, Private Wealth Management [email protected] 4157057159 Wills, trusts, foundations, and wealth planning strategies have legal, tax, accounting, and other implications. Clients should consult a legal or tax advisor. ©2017 MUFG Union Bank, N.A. All rights reserved. Member FDIC. Union Bank is a registered trademark and brand name of MUFG Union Bank, N.A. EAP full-page template.indd 1 7/17/17 3:08 PM CONTENTS OCTOBER 2017 4 / CALENDAR 6 / THE SYMPHONY 10 / NEWS FEATURES 12 / BERLIOZ’S BARGAIN 14 / MUSIC & IMAGINATION CONCERTS 15 / October 5 & 7 ENIGMA VARIATIONS 19 / October 6 ELGAR UNTUXED 21 / October 12 & 14 GIDON KREMER SCHUMANN VIOLIN CONCERTO 24 / October 13 [UNTITLED] 1 26 / October 17 NOSFERATU: A SYMPHONY OF HORROR 27 / October 20, 21 & 27 VIVALDI FOUR SEASONS 30 / October 26 & 29 21 / GIDON KREMER SHOSTAKOVICH SYMPHONY NO. -

Reprints Italian Pianist Beatrice Rana on Tri-C

reprints Italian pianist Beatrice Rana on Tri-C Series at the Cleveland Museum of Art (October 5) by Daniel Hathaway Director Emanuela Friscioni has chosen to take a new tack with this season’s Tri-C Classical Piano series at the Cleveland Museum of Art. Three Sunday afternoon recitals will showcase young pianists who are beginning to come to international prominence, commencing with 21-year-old Italian pianist Beatrice Rana, who won the silver medal at the fourteenth Van Cliburn Competition in Fort Worth in 2013. Rana, who demonstrates an elegant and engaging stage presence, had the opportunity to show her keyboard prowess on Sunday, October 5 in Gartner Auditorium in a program of music by J.S. Bach, Frederic Chopin and Sergei Prokofiev. The centerpiece of her program was Chopin’s Sonata No. 2 in b-flat, op. 35. Summoning up a vast range of dynamics and color, Rana skillfully built up approaches to fearsome climaxes without thickening Chopin’s textures. Her bravura playing in the Scherzo was followed by her steady, inexorable pacing of the funeral march, relieved by a sotto voce middle section of transcendent calm. She cloaked the final Presto in a velvet haze that retained its character right up to the final, dismissive chords. Prokofiev’s Sonata No. 6 in A, op. 82, followed the Chopin after what seemed like an unnecessary intermission. Rana played with fingers of steel in its violent passages, then offered a complete contrast with the measured, separated chords of the second movement Allegretto. The strange Tempo di valzer lentissimo disappeared into nothingness at the end, leading to a strongly rhythmic, scampering toccata with clear, crystalline voicings and hammered repeated notes. -

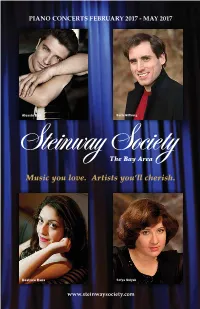

Steinway Society 16-17 Program Two (Pdf)

PIANO CONCERTS FEBRUARY 2017 - MAY 2017 Alessio Bax Boris Giltburg Steinway TheSociety Bay Area Music you love. Artists you’ll cherish. Beatrice Rana Sofya Gulyak 1 www.steinwaysociety.com PIANO CONCERTS 2016–2017 Letter from the President Jon Nakamatsu mozart brahmS Schumann chopin Dear Friends and Patrons, September 11, 2016, 7:00 p.m. Welcome to our exciting 2016 – 2017 Season. Thank McAfee Performing Arts and Lecture Center, Saratoga you for supporting Steinway Society’s internationally acclaimed pianists as they bring beloved masterworks Fei-Fei Dong to our community. Galuppi Schumann chopin leibermann liSzt October 15, 2016, 7:30 p.m. The season begins with local treasure Jon Nakamatsu, 1997 Van Trianon Theatre, San Jose Cliburn Competition Gold Medalist, now celebrated worldwide. Our October concert presents the rising young Chinese pianist Fei-Fei Vyacheslav Gryaznov Dong a finalist at the 2013 Van Cliburn competition. beethoven debussy ravel prokoFiev rachmaninov Russian virtuoso Vyacheslav Gryaznov, winner of the Rubinstein November 12, 2016, 7:30 p.m. and Rachmaninoff Competitions in Moscow joins us in November Trianon Theatre, San Jose with a program that includes a premiere performance of his transcription of Prokofiev’s “Sur la Borysthene.” The celebrated Klara Frei and Temirzhan Yerzhanov piano duo Frei and Yerzhanov perform Romantic Period favorites Schubert brahmS mendelssohn Schumann in January, 2017. Exhilarating artist Alessio Bax, soloist with more January 21, 2017, 7:30 p.m. than 100 orchestras since winning the Leeds International Piano Trianon Theatre, San Jose Competition, will thrill in February. March presents the brilliant Boris Giltburg, who won First Prize at the 2013 Queen Elisabeth Alessio Bax Competition (Brussels) and performs internationally with esteemed mozart Schubert Scriabin ravel conductors. -

Gimeno Conducts Daphnis Et C

Toronto Symphony Orchestra Sir Andrew Davis, Interim Artistic Director Wednesday, October 9, 2019 at 8:00pm Thursday, October 10, 2019 at 8:00pm Saturday, October 12, 2019 at 8:00pm Gimeno Conducts Daphnis et Chloé Gustavo Gimeno, conductor Beatrice Rana, piano Guillaume Connesson Aleph: Danse symphonique (TSO Co-commission) Sergei Prokofiev Piano Concerto No. 3 in C Major, Op. 26 I. Andante – Allegro II. Andantino III. Allegro ma non troppo Intermission Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky The Tempest Fantasy-Overture, Op. 18 Please stay in your seats Maurice Ravel after the concert for Suite No. 2 from Daphnis et Chloé a chat with incoming Music Director Gustavo I. Lever du jour Gimeno and TSO Chief II. Pantomime Executive Officer III. Danse générale Matthew Loden. The appearance of Gustavo Gimeno is generously supported by Philip & Eli Taylor and Invesco Ltd. The post-performance conversations with Gustavo Gimeno are generously supported by Peter & Margie Kelk. The October 9 performance is generously supported by Marianne Oundjian to welcome Gustavo Gimeno. As a courtesy to musicians, guest artists, and fellow concertgoers, please put your phone away and on silent during the performance. OCTOBER 9, 10 & 12, 2019 29 ABOUT THE WORKS Guillaume Connesson of seven notes. The work begins with a huge Aleph: Danse symphonique fortissimo chord, which releases waves of (TSO Co-commission) energy. A pulse establishes itself and the main theme gradually takes shape. Particles of Born: Boulogne-Billancourt, France, matter assemble themselves together, until May 5, 1970 a new chord releases a tumultuous energy. Composed: 2007 After this introduction, the dance proper 15 min begins: the main theme passes from one desk of instruments to another, initially light and rhythmic in character, then becoming Guillaume Connesson’s Aleph is the first part increasingly turbulent. -

MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL Recordings of the Year 2017

MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL Recordings Of The Year 2017 This is the fourteenth year that Musicweb International has asked its reviewing team to nominate their recordings of the year. Reviewers are not restricted to discs they had reviewed, but the choices must have been reviewed on MWI in the last 12 months (December 2016-November 2017). The 136 selections have come from 27 members of the team and 68 different labels, the choices reflecting as usual, the great diversity of music and sources. Of the selections, seven have received two nominations: Iván Fischer’s Mahler 3 on Channel Classics Late works by Elliott Carter on Ondine Tommie Haglund’s Cello concerto on BIS Beatrice Rana’s Goldberg Variations on Warner Unreleased recordings by Wanda Luzzato on Rhine Classics Krystian Zimerman’s late Schubert sonatas on Deutsche Grammophon Vaughan Williams London Symphony on Hyperion Two labels – Deutsche Grammophon and Hyperion – gained the most nominations, nine apiece, considerably more than any other label. MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL RECORDING OF THE YEAR In this twelve month period, we published more than 2700 reviews. There is no easy or entirely satisfactory way of choosing one above all others as our Recording of the Year. In some years, there have been significant anniversaries of composers or performers to help guide the selection, but not so in 2017. Johann Sebastian BACH Goldberg Variations - Beatrice Rana (piano) rec. 2016 WARNER CLASSICS 9029588018 In the end, it was the unanimity of the two reviewers who nominated Beatrice Rana’s Goldberg Variations – “easily my individual Record of the Year” and “how is it possible that she can be only 23” – that won the day. -

ROBERT SCHUMANN (1810-1856) Symphonic Études, Op

Beatrice Rana SILVER MEDALIST ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Cover: photo, Ellen Appel—Mike Moreland / The Cliburn. Graphic Design: Karin Elsener Publishers: Boosey & Hawkes Inc. (Bartók), SDRM/Éditions Duran S.A. (Ravel) All texts and translations C harmonia mundi usa P C 2013 harmonia mundi usa 1117 Chestnut Street, Burbank, California 91506 Recorded in concert May 24–June 9, 2013 FOURTEENTH at Bass Performance Hall, Fort Worth, Texas VAN CLIBURN Audio Engineer: Tom Lazarus, Classic Sound, Inc. Mastering: Brad Michel INTERNATIONAL Producers: Richard Dyer, Jacques Marquis, Robina G. Young PIANO COMPETITION 1 14th Van Cliburn International Piano Competition / BEATRICE RANA HMU 907606 © harmonia mundi usa ABOUT THE PROGRAM ROBERT SCHUMANN (1810-1856) Symphonic Études, Op. 13 (1837) 24’56 n the early 1830s, Robert Schumann (1810-1856) received Conservatoire in 1895 for failing to win any further awards. what every pianist dreads: an injury to his right hand. Though Undaunted, he returned two years later and among the tight-knit 1 Thema: Andante 1’31 it is not clear what caused it (accounts vary from a repetitive group of like-minded composers and musicians he met while 2 Etude I: Un poco più vivo 1’18 Istrain injury to the side effects of his syphilis medication), by studying there was Ricardo Viñes – one of the most celebrated 3 Etude II 3’09 1839 Schumann had lost complete use of that hand and was young virtuoso pianists of his day. 4 Etude III: Vivace 1’13 forced to abandon his plans as a pianist. Schumann’s love for the Known for his premieres of difficult and often controversial 5 Etude IV ’58 piano never diminished, but many of his works are tainted by a new music, Viñes became Ravel’s muse and in early 1909 he poignant sense of ‘what if’. -

Edition 3 | 2018-2019

EASTMAN • THE ATRE 2018-2019 SEASON EXPERIENCE EASTMAN EXCELLENCE KILBOURN EASTMAN FERNANDO BARBARA B. SMITH CONCERT RANLET LAIRES PIANO WORLD MUSIC SERIES SERIES SERIES SERIES MARCH 2019 – APRIL 2019 insidewhat’s Welcome From the Director | 5 Ying Quartet with PUSH Physical Theatre | 28 The Historian’s Corner | 8 Roby Lakatos Ensemble | 32 Beatrice Rana | 10 Ying Quartet | 36 Joshua Roman | 13 Joshua Bell & David Zinman | 39 Disney in Concert: Afro-Cuban All Stars | 44 A Silly Symphony Celebration | 17 Gamelan Lila Muni & Elias String Quartet | 25 Gamelan Sanjiwani | 48 CONTACT US: Location: Eastman School of Music – ESM 101 EASTMAN THEATRE BOX OFFICE Phone: (585) 274-1109 Mailing Address E-mail: [email protected] Eastman School of Music Concert Office 26 Gibbs Street Mike Stefiuk, Director of Concert Operations Rochester, NY 14604 Julia Ng, Assistant Director of Concert Operations Eastman Theatre Box Office Greg Machin, Ticketing and Box Office Manager 433 East Main Street Joseph Broadus, Box Office Supervisor Rochester, NY 14604 Christine Benincasa, Secretary Ron Stackman, Director of Stage Operations, Phone Eastman Theatre Eastman Theatre Box Office: (585) 274-3000 Jules Corcimiglia, Assistant Director of Stage Lost & Found: (585) 274-3000 Operations (Kodak Hall) Eastman Concert Office: (585) 274-1109 Daniel Mason, Assistant Director of Stage Hall Rentals: (585) 274-1109 Operations (Kilbourn Hall) Michael Dziakonas, Assistant Director of Stage Operations (Hatch Recital Hall) ADVERTISING This program is published in association with Onstage Publications, Onstage Publications 1612 Prosser Avenue, Kettering, OH 45409. This program may not be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the 937-424-0529 | 866-503-1966 publisher. -

French Classics

FRENCH CLASSICS 23–26 NOVEMBER 2018 Arts Centre Melbourne, Hamer Hall CONCERT PROGRAM Melbourne Symphony Orchestra Fabien Gabel conductor Beatrice Rana piano Fiona Campbell mezzo-soprano Melbourne Symphony Orchestra Chorus Warren Trevelyan-Jones chorus master Debussy Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune Prokofiev Piano Concerto No.3 INTERVAL Debussy/Dean Ariettes Oubliées Ravel Daphnis et Chloé, Suite No.2 Pre-concert talk (Friday & Saturday) Join Megan Stellar, founder and editor of Rehearsal Magazine, for a pre-concert conversation on-stage at Hamer Hall from 6.15pm. Post-concert conversation (Monday) Join composer and ABC Classic FM producer, Andrew Aronowicz, for a post-concert conversation inside the Stalls Foyer of Hamer Hall from 8.30pm. Running time: One hour and 45 minutes, including a 20-minute interval In consideration of your fellow patrons, the MSO thanks you for silencing and dimming the light on your phone. The MSO acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the land on which it is performing. MSO pays its respects to their Elders, past and present, and the Elders from other mso.com.au communities who may be in attendance. (03) 9929 9600 2 MELBOURNE SYMPHONY FABIEN GABEL ORCHESTRA CONDUCTOR Established in 1906, the Melbourne Fabien Gabel is music director of the Symphony Orchestra (MSO) is an Quebec Symphony Orchestra, and was arts leader and Australia’s oldest appointed music director of the French professional orchestra. Chief Youth Orchestra in 2017. Conductor Sir Andrew Davis has His 2017–18 schedule saw guest been at the helm of MSO since 2013. appearances with the Cleveland Engaging more than 4 million people Orchestra at their Blossom Festival, each year, the MSO reaches diverse the Royal Flemish Philharmonic, Hessian audiences through live performances, Radio Symphony Orchestra, Detroit recordings, TV and radio broadcasts Symphony Orchestra, Staatskapelle and live streaming. -

Steinway Society 16-17 Program One (Pdf)

PIANO CONCERTS SEPTEMBER 2016 - JANUARY 2017 Jon Nakamatsu Fei-Fei Dong Steinway TheSociety Bay Area Music you love. Artists you’ll cherish. Vyacheslav Gryaznov Klara Frei and Temirzhan Yerzhanov 1 www.steinwaysociety.com PIANO CONCERTS 2016–2017 Letter from the President Jon Nakamatsu mozart brahmS Schumann chopin Dear Friends and Patrons, September 11, 2016, 7:00 p.m. Welcome to our exciting 2016 – 2017 Season. Thank McAfee Performing Arts and Lecture Center, Saratoga you for supporting Steinway Society’s internationally acclaimed pianists as they bring beloved masterworks Fei-Fei Dong to our community. Galuppi Schumann chopin leibermann liSzt October 15, 2016, 7:30 p.m. The season begins with local treasure Jon Nakamatsu, 1997 Van Trianon Theatre, San Jose Cliburn Competition Gold Medalist, now celebrated worldwide. Our October concert presents the rising young Chinese pianist Fei-Fei Vyacheslav Gryaznov Dong a finalist at the 2014 Van Cliburn competition. beethoven debussy ravel prokoFiev rachmaninov Russian virtuoso Vyacheslav Gryaznov, winner of the Rubinstein November 12, 2016, 7:30 p.m. and Rachmaninoff Competitions in Moscow joins us in November Trianon Theatre, San Jose with a program that includes a premiere performance of his transcription of Prokofiev’s “Sur la Borysthene.” The celebrated Klara Frei and Temirzhan Yerzhanov piano duo Frei and Yerzhanov perform Romantic Period favorites Schubert brahmS mendelssohn Schumann in January, 2017. Exhilarating artist Alessio Bax, soloist with more January 21, 2017, 7:30 p.m. than 100 orchestras since winning the Leeds International Piano Trianon Theatre, San Jose Competition, will thrill in February. March presents the brilliant Boris Giltberg, who won First Prize at the 2013 Queen Elisabeth Alessio Bax Competition (Brussels) and performs internationally with esteemed mozart Schubert Scriabin ravel conductors. -

Beatrice Rana Ha Già Scosso Il Mondo Della Musica Classica Internazionale, Danish National Symphony Orchestra E La Filarmonica Di San Pietroburgo

Realizzato con il contributo di Soci Fondatori BEATRICE 8 NOVEMBRE ore 20.30 RANA Pianoforte programma Fryderyk Chopin 4 Scherzi: op. 20, op. 31, op. 39 e op. 54 Isaac Albeniz El Albaicín, da Iberia – Libro 3 Maurice Ravel La Valse Assez lent ; Modéré; Assez animé; Presque lent; Assez vif; Moins vif; Épilogue: Lent Beatrice Rana ha già scosso il mondo della musica classica internazionale, Danish National Symphony Orchestra e la Filarmonica di San Pietroburgo. suscitando ammirazione e interesse da parte di presentatori di concerti, Nel corso delle prossime stagioni Beatrice Rana debutterà con la New direttori, critici e pubblico in molti paesi. York Philharmonic, l’Orchestre de Paris, l’Orchestra Sinfonica di Boston, Beatrice Rana si esibisce nelle sale da concerto e nei festival più la Deutsches Sinfonie Orchester, la London Symphony Orchestra e tornerà rinomati al mondo, tra cui il Konzerthaus e il Musikverein di Vienna, la alla Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, alla Danish National Symphony Berlin Philharmonie, il Concertgebouw di Amsterdam, il Lincoln Center Orchestra, alla Dallas Symphony Orchestra, alla Toronto Symphony e la Carnegie Hall di Amsterdam, la Tonhalle di Zurigo, la Wigmore Hall Orchestra, alla Filarmonica della Scala, all’Orchestra dell’Accademia di di Londra, la Royal Albert Hall e la Royal Festival Hall, il Théâtre des Santa Cecilia e all’Orchestra Sinfonica di Anversa. Terrà inoltre tournée Champs-Elysées di Parigi, la KKL di Lucerna, la Philharmonie di Colonia, con i Wiener Symphoniker e Andrés Orozco-Estrada, l’LSO e Gianandrea la Philharmonie, il Prinzregententheater e la Herkulessaal di Monaco, Alte Noseda, l’Orchestra Filarmonica del Lussemburgo e Gustavo Gimeno, la Oper di Francoforte, la Società dei Concerti di Milano, Ferrara Musica, il Philharmonia di Zurigo e Fabio Luisi. -

Russian Masters | the Philadelphia Orchestra

23 Season 2018-2019 Thursday, June 6, at 7:30 Saturday, June 8, at 8:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Beatrice Rana Piano Stravinsky Funeral Song, Op. 5 First Philadelphia Orchestra performances ProkofievPiano Concerto No. 3 in C major, Op. 26 I. Andante—Allegro II. Theme (Andantino) and Variations III. Allegro ma non troppo Intermission Rachmaninoff Symphony No. 1 in D minor, Op. 13 I. Grave—Allegro ma non troppo II. Allegro animato III. Larghetto IV. Allegro con fuoco—Largo—Con moto This program runs approximately 2 hours. These concerts are presented in cooperation with the Sergei Rachmaninoff Foundation. The June 6 concert is sponsored by Tobey and Mark Dichter. The June 6 concert is also sponsored by Ballard Spahr. The June 8 concert is sponsored by Allan Schimmel in memory of Reid B. Reames. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM, and are repeated on Monday evenings at 7 PM on WRTI HD 2. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 24 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra Philadelphia is home and orchestra, and maximizes is one of the preeminent the Orchestra continues impact through Research. orchestras in the world, to discover new and The Orchestra’s award- renowned for its distinctive inventive ways to nurture winning Collaborative sound, desired for its its relationship with its Learning programs engage keen ability to capture the loyal patrons at its home over 50,000 students, hearts and imaginations of in the Kimmel Center, families, and community audiences, and admired for and also with those who members through programs a legacy of imagination and enjoy the Orchestra’s area such as PlayINs, side-by- innovation on and off the performances at the Mann sides, PopUP concerts, concert stage. -

Livret / Booklet Edi Tor: Michel Ferland

Beatrice Rana Chopin T 26 Préludes Scriabine T Sonate n o 2 op. 19 1er PRIX PIANO 2011 ACD2 2614 ATM A Classique FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN 1810-1849 Préludes op. 28 orsqu’en novembre 1830, Frédéric Chopin, âgé de vingt auxquelles se joignent notamment Liszt, Delacroix et Balzac. Parmi les œuvres commen - Lans, quitte sa famille et sa Pologne natale au bord de la cées ou composées au château de la romancière figurent plusieurs nocturnes et mazurkas, révolte contre l’occupant russe, il emporte pour toujours la Sonate n o 2 en si bémol mineur ainsi que les Préludes opus28. dans ses bagages une immense nostalgie: «Je crois que je Chopin, dont la santé est fragile, souffre de phtisie, un mal alors incurable et jugé conta - pars pour mourir, et comme cela doit être triste de mourir gieux. En novembre 1838, dans l’espoir d’améliorer son état, George Sand l’emmène à autre part que là où l’on a vécu», écrit-il à son meilleur ami Majorque, aux îles Baléares. Malheureusement, le climat hivernal est tout sauf salutaire Titus Woyciechowski. Cet incurable mal du pays, cet atta - pour l’infortuné Chopin et, devant le refus des aubergistes de loger le malade, le couple chement envers la mère patrie qu’il ne reverra jamais, et les enfants de George s’installent dans un monastère désaffecté, la chartreuse de Vall - Chopin les a immortalisés dans sa musique de piano, tout demossa. « Ma cellule a la forme d’un grand cercueil » écrit Chopin. « On peut hurler ... particulièrement dans ses Polonaises et ses Mazurkas .