Beatrice Rana, Piano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seattle Symphony October 2017 Encore

OCTOBER 2017 LUDOVIC MORLOT, MUSIC DIRECTOR BEATRICE RANA PLAYS PROKOFIEV GIDON KREMER SCHUMANN VIOLIN CONCERTO LOOKING AHEAD: MORLOT C O N D U C T S BERLIOZ CONTENTS My wealth. My priorities. My partner. You’ve spent your life accumulating wealth. And, no doubt, that wealth now takes many forms, sits in many places, and is managed by many advisors. Unfortunately, that kind of fragmentation creates gaps that can hold your wealth back from its full potential. The Private Bank can help. The Private Bank uses a proprietary approach called the LIFE Wealth Cycle SM to ind those gaps—and help you achieve what is important to you. To learn more, please visit unionbank.com/theprivatebank or contact: Lisa Roberts Managing Director, Private Wealth Management [email protected] 4157057159 Wills, trusts, foundations, and wealth planning strategies have legal, tax, accounting, and other implications. Clients should consult a legal or tax advisor. ©2017 MUFG Union Bank, N.A. All rights reserved. Member FDIC. Union Bank is a registered trademark and brand name of MUFG Union Bank, N.A. EAP full-page template.indd 1 7/17/17 3:08 PM CONTENTS OCTOBER 2017 4 / CALENDAR 6 / THE SYMPHONY 10 / NEWS FEATURES 12 / BERLIOZ’S BARGAIN 14 / MUSIC & IMAGINATION CONCERTS 15 / October 5 & 7 ENIGMA VARIATIONS 19 / October 6 ELGAR UNTUXED 21 / October 12 & 14 GIDON KREMER SCHUMANN VIOLIN CONCERTO 24 / October 13 [UNTITLED] 1 26 / October 17 NOSFERATU: A SYMPHONY OF HORROR 27 / October 20, 21 & 27 VIVALDI FOUR SEASONS 30 / October 26 & 29 21 / GIDON KREMER SHOSTAKOVICH SYMPHONY NO. -

Program Notes

March 16-17, 2019, page 1 programBY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA notes , Fantasy- theme suggests the fury and confusion Romeo and Juliet of a fight. The love theme (used here Overture (1869) as a contrasting second theme) repre- ■ PETER ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY 1840- sents Romeo’s passion; a tender, sighing 1893 phrase for muted violins suggests Juliet’s Romeo and Juliet was written when response. A stormy development section Tchaikovsky was 29. It was his first denotes the continuing feud and Friar masterpiece. For a decade, he had been Lawrence’s pleas for peace. The crest of involved with the intense financial, per- the fight ushers in the recapitulation, in sonal and artistic struggles that mark the which the thematic material from the ex- maturing years of most creative figures. position is considerably compressed. The Advice and guidance often flowed his tempo slows, the mood darkens, and the way during that time, and one who dis- coda emerges with a sense of impend- pensed it freely to anyone who would lis- ing doom. A funereal drum beats out ten was Mili Balakirev, one of the group the cadence of the lovers’ fatal pact. The of amateur composers known in English closing woodwind chords evoke visions as “The Five” (and in Russian as “The of the flight to celestial regions. Mighty Handful”) who sought to create a nationalistic music specifically Russian Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor, in style. In May 1869, Balakirev sug- Op. 26 (1865-1866) gested to Tchaikovsky that Shakespeare’s MAX BRUCH ■ 1838-1920 Romeo and Juliet would be an appropri- ate subject for a musical composition, German composer, conductor and and he even offered the young composer teacher Max Bruch, widely known and a detailed program and an outline for the respected in his day, received his earli- form of the piece. -

Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770-1827)

21M011 (spring, 2006) Ellen T. Harris Lecture VII Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Like Monteverdi, who bridges the Renaissance and the Baroque, Beethoven stands between two eras, not fully encompassed by either. He inherited the Classical style through Mozart and Haydn, and this is represented in works from what is typically called his “first period” (to about 1800), during which time Beethoven performed actively as a virtuoso pianist. The “middle period” (about 1800 to 1818) saw Beethoven break through the classical templates as he wrestled with his increasing deafness, the growing inability to perform or conduct, and his disillusion with Napoleon, whom he had considered a hero of the French Revolution until Napoleon declared himself Emperor in 1804. 1802: Heiligenstadt Testament depicts Beethoven’s desolation over his deafness; 1803: composition of the 3rd Symphony, originally titled Bonaparte, but changed to Eroica after, 1804: Napoleon declares himself Emperor 1808: 5th Symphony in C minor, Op. 67 From Beethoven’s middle period come the works most often associated with Beethoven and with what is known of his personality: forceful, uncompromising, angry, willful, suffering, but overcoming extraordinary personal hardship, all of which traits are read into his music. The Romantic cult of the individual who represents himself in his music and of the genius who suffers for his art begins here with Beethoven. Beethoven’s “late period” (1818 to his death [1827]) becomes more introspective and abstract, as Beethoven’s deafness increasingly forces him to retreat into himself. Although the 9th Symphony dates from these years, it is the only symphony to do so, and, in many respects, is a throwback to the middle period. -

Reprints Italian Pianist Beatrice Rana on Tri-C

reprints Italian pianist Beatrice Rana on Tri-C Series at the Cleveland Museum of Art (October 5) by Daniel Hathaway Director Emanuela Friscioni has chosen to take a new tack with this season’s Tri-C Classical Piano series at the Cleveland Museum of Art. Three Sunday afternoon recitals will showcase young pianists who are beginning to come to international prominence, commencing with 21-year-old Italian pianist Beatrice Rana, who won the silver medal at the fourteenth Van Cliburn Competition in Fort Worth in 2013. Rana, who demonstrates an elegant and engaging stage presence, had the opportunity to show her keyboard prowess on Sunday, October 5 in Gartner Auditorium in a program of music by J.S. Bach, Frederic Chopin and Sergei Prokofiev. The centerpiece of her program was Chopin’s Sonata No. 2 in b-flat, op. 35. Summoning up a vast range of dynamics and color, Rana skillfully built up approaches to fearsome climaxes without thickening Chopin’s textures. Her bravura playing in the Scherzo was followed by her steady, inexorable pacing of the funeral march, relieved by a sotto voce middle section of transcendent calm. She cloaked the final Presto in a velvet haze that retained its character right up to the final, dismissive chords. Prokofiev’s Sonata No. 6 in A, op. 82, followed the Chopin after what seemed like an unnecessary intermission. Rana played with fingers of steel in its violent passages, then offered a complete contrast with the measured, separated chords of the second movement Allegretto. The strange Tempo di valzer lentissimo disappeared into nothingness at the end, leading to a strongly rhythmic, scampering toccata with clear, crystalline voicings and hammered repeated notes. -

Requirements for Audition Sub-Principal Percussion

Requirements for Audition 1 Requirements for Audition Sub-Principal Percussion March 2019 The NZSO tunes at A440. Auditions must be unaccompanied. Solo 01 | BACH | LUTE SUITE IN E MINOR MVT. 6 – COMPLETE (NO REPEATS) 02 | DELÉCLUSE | ETUDE NO. 9 FROM DOUZE ETUDES - COMPLETE Excerpts BASS DRUM 7 03 | BRITTEN | YOUNG PERSON’S GUIDE TO THE ORCHESTRA .................................. 7 04 | MAHLER | SYMPHONY NO. 3 MVT. 1 ......................................................................... 8 05 | PROKOFIEV | SYMPHONY NO. 3 MVT. 4 .................................................................... 9 06 | SHOSTAKOVICH | SYMPHONY NO. 11 MVT. 1 .........................................................10 07 | STRAVINSKY | RITE OF SPRING ...............................................................................10 08 | TCHAIKOVSKY | SYMPHONY NO. 4 MVT. 4 ..............................................................12 BASS DRUM WITH CYMBAL ATTACHMENT 13 09 | STRAVINSKY | PETRUSHKA (1947) ...........................................................................13 New Zealand Symphony Orchestra | Sub-Principal Percussion | March 2019 2 Requirements for Audition CYMBALS 14 10 | DVOŘÁK | SCHERZO CAPRICCIOSO ........................................................................14 11 | MUSSORGSKY | NIGHT ON BALD MOUNTAIN .........................................................14 12 | RACHMANINOV | PIANO CONCERTO NO. 2 MVT. 3 ................................................15 13 | SIBELIUS | FINLANDIA ................................................................................................15 -

Classic Terms

Classic Terms Alberti Bass: "Broken" arpeggiated triads in a bass line, common in many types of Classic keyboard music; named after Domenico Alberti (1710-1740) who used it extensively but did not invent it. Aria: A lyrical type of singing with a steady beat, accompanied by orchestra; a songful monologue or duet in an opera or other dramatic vocal work. Bel Canto: (Italian for "beautiful singing") An Italian singing tradition primarily in opera seria and opera buffa in the late17th- to early-19th century. Characterized by seamless phrasing (legato), great breath control, flexibility, tone, and agility. Most often associated with singing done in the early-Romantic operas of Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti. Cadenza: An improvised or written-out ornamental virtuosic passage played by a soloist in a concerto. In Classic concertos, a cadenza occurs at a dramatic moment before the end of a movement, when the orchestra stops so the soloist can play in free time, and then after the cadenza is finished the orchestra reenters to bring the movement to its conclusion. Castrato The term for a male singer who was castrated before puberty to preserve his high soprano range (this practice in Italy lasted until the late 1800s). Today, the rendering of castrato roles is problematic because it requires either a male singing falsetto (weak) or a mezzo-soprano (strong, but woman must impersonate a man). Counterpoint: Combining two or more independent melodies to make an intricate polyphonic texture. Empindsam: (German for "sensitive") The term used to describe a highly-expressive style of German pre- Classic/early Classic instrumental music, that was intended to intensely express true and natural feelings, featuring sudden contrasts of mood. -

Bela Bartok's "Scherzo for Piano and Orchestra", Op

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1995 Bela Bartok's "Scherzo for Piano and Orchestra", Op. 2: An Analytical Study. Richard Douglas Seiler Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Seiler, Richard Douglas Jr, "Bela Bartok's "Scherzo for Piano and Orchestra", Op. 2: An Analytical Study." (1995). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6135. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6135 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. Hie quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margin*, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced tty sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections withsmall overlaps. -

Graduate Piano Recital

Pittsburg State University Pittsburg State University Digital Commons Electronic Thesis Collection 5-2016 GRADUATE PIANO RECITAL Nan Sun Pittsburg State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pittstate.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Sun, Nan, "GRADUATE PIANO RECITAL" (2016). Electronic Thesis Collection. 90. https://digitalcommons.pittstate.edu/etd/90 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Pittsburg State University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Pittsburg State University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GRADUATE RECITAL A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Music Nan Sun Pittsburg State University Pittsburg, Kansas May, 2016 GRADUATE PIANO RECITAL Nan Sun APPROVED: Thesis Advisor __________________________________________________________ Reena Natenberg, Department of Music Committee Member______________________________________________________ John Ross, Department of Music Committee Member __________________________________________________________ Ray Willard, Department of Teaching and Leadership GRADUATE PIANO RECITAL An Abstract of the Thesis by Nan Sun This thesis contains information pertaining to my Graduate Piano Recital. The recital consists of the following works: Piano Sonata Op. 26 by Ludwig Van Beethoven; French Suite No. 2 by Johann Sebastian -

The Ballades of Frederic Chopin

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects 12-1-1981 The alB lades of Frederic Chopin Janell E. Brakel Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Recommended Citation Brakel, Janell E., "The alB lades of Frederic Chopin" (1981). Theses and Dissertations. 451. https://commons.und.edu/theses/451 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ' 1 f. 1 'c' ,.!'l)~r,T(' ,.,H.,L l, ]3"11 .... J_.;/\ D' ••• ; 'J''1' · ...:'"· 1"i'_ ·, l·,r\ _ . Li1· Janl"ll E. Brakel Bachelor af Science, Mayville State Coll~ge, 1978 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial fulfillnl\'!nt of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Grand Forks, North Dakota December 1981 I ' ' ,........I 'J-·liis 'l'he:;i.s su:Omitted by Janell E. Brakel in partir1l fulfillment of tl1e requirements for the Degree of !>laster nf Art:s from the University of North Dakota is h~reby ap proved Ly the Faculty Advisory Conunittee under whom the work has been done. ' / I' -'' , ~ _/ ,. ' , ,'I / - ,' ' I ./ , I' -~ v (Chairman) c - ' ' ' - ' This Thesis meets the standards for appearance and confor~s to the style and format requirements of the Graduate School of the University of i'Jorth Dakota, and is hereby approved . -

Utilizing Standard Violin Orchestral Excerpts As A

UTILIZING STANDARD VIOLIN ORCHESTRAL EXCERPTS AS A PEDAGOGICAL TOOL: AN ANALYTICAL STUDY GUIDE WITH FUNCTIONAL EXERCISES Ai-Wei Chang, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2014 APPROVED: Felix Olschofka, Major Professor Clay Couturiaux, Committee Member Susan Dubois, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in College of Music James Scott, Dean of the College of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Chang, Ai-Wei. Utilizing Standard Violin Orchestral Excerpts as a Pedagogical Tool: An Analytical Study Guide with Functional Exercises. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2014, 83 pp., 18 examples, 24 figures, 24 exercises, bibliography, 53 titles. Orchestral excerpts have been used as a teaching material by violin pedagogues to develop violin techniques in addition to scales and etudes in the twentieth century. However, instructions on developing specific techniques and the relationship to its musical content have been left out. This dissertation provides an analytical study guide addressing the common challenges for violinists. Ten orchestral excerpts are selected from surveying frequently requested orchestral excerpts for the first violin. Through analysis of each excerpt, insight from the other violinists and pedagogues are included. Fifty-four functional exercises with comments are created to help violinists practice effectively and serve as a pedagogical tool -

Steinway Society 16-17 Program Two (Pdf)

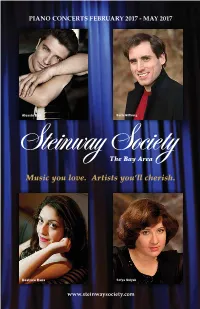

PIANO CONCERTS FEBRUARY 2017 - MAY 2017 Alessio Bax Boris Giltburg Steinway TheSociety Bay Area Music you love. Artists you’ll cherish. Beatrice Rana Sofya Gulyak 1 www.steinwaysociety.com PIANO CONCERTS 2016–2017 Letter from the President Jon Nakamatsu mozart brahmS Schumann chopin Dear Friends and Patrons, September 11, 2016, 7:00 p.m. Welcome to our exciting 2016 – 2017 Season. Thank McAfee Performing Arts and Lecture Center, Saratoga you for supporting Steinway Society’s internationally acclaimed pianists as they bring beloved masterworks Fei-Fei Dong to our community. Galuppi Schumann chopin leibermann liSzt October 15, 2016, 7:30 p.m. The season begins with local treasure Jon Nakamatsu, 1997 Van Trianon Theatre, San Jose Cliburn Competition Gold Medalist, now celebrated worldwide. Our October concert presents the rising young Chinese pianist Fei-Fei Vyacheslav Gryaznov Dong a finalist at the 2013 Van Cliburn competition. beethoven debussy ravel prokoFiev rachmaninov Russian virtuoso Vyacheslav Gryaznov, winner of the Rubinstein November 12, 2016, 7:30 p.m. and Rachmaninoff Competitions in Moscow joins us in November Trianon Theatre, San Jose with a program that includes a premiere performance of his transcription of Prokofiev’s “Sur la Borysthene.” The celebrated Klara Frei and Temirzhan Yerzhanov piano duo Frei and Yerzhanov perform Romantic Period favorites Schubert brahmS mendelssohn Schumann in January, 2017. Exhilarating artist Alessio Bax, soloist with more January 21, 2017, 7:30 p.m. than 100 orchestras since winning the Leeds International Piano Trianon Theatre, San Jose Competition, will thrill in February. March presents the brilliant Boris Giltburg, who won First Prize at the 2013 Queen Elisabeth Alessio Bax Competition (Brussels) and performs internationally with esteemed mozart Schubert Scriabin ravel conductors. -

An Analysis of the Musical Writing Features of Chopin's Scherzo No. 2

2018 2nd International Conference on Social Sciences, Arts and Humanities (SSAH 2018) An Analysis of the Musical Writing Features of Chopin’s Scherzo No. 2 in B-flat minor Yu Liu Xi’an Shiyou University, Xi’an Shaanxi, 710065, China Keywords: Chopin, Harmonic music, Creative characteristics. Abstract: Scherzo No. 2 in B-flat minor is the most famous one of Chopin's four piano harmonies. This article analyzes and summarizes the important piano works by Scherzo No. 2 in B-flat minor. Each part of the music image, musical composition and musical characteristics elaborates the musical composition of Scherzo No. 2 in B-flat minor. 1. Introduction Chopin Scherzo No. 2 in B-flat minor was published in December 1837 and entitled "The Duchess of Forststein." During this period, Chopin was in the full period of artistic creation. Therefore, the work was beautifully melodious, passionate and passionate, and the mood of the music was slow and urgent. There was no tragic factor at all and it showed a very high artistic achievement. The song also became Chopin IV. The most famous one in the first twist. In the sonatas and symphonies, Beethoven used harpsichords instead of mini-steps, which laid a strong brush on the development of harbuterism. After inheriting the creative skills of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, Chopin has greatly developed this genre. Chopin's treacherous music is large in scale, profound in content, complex in structure, and rich in change. It is not limited to displaying witty and humorous styles. The combination of diverse melody and complex and varied character traits has transformed Chopin's scherzo into a new one, almost becoming a A new kind of music genre.