Russian Masters | the Philadelphia Orchestra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Season 2018-2019 the Philadelphia Orchestra

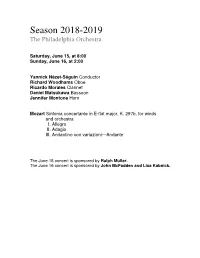

Season 2018-2019 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, June 15, at 8:00 Sunday, June 16, at 2:00 Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Richard Woodhams Oboe Ricardo Morales Clarinet Daniel Matsukawa Bassoon Jennifer Montone Horn Mozart Sinfonia concertante in E-flat major, K. 297b, for winds and orchestra I. Allegro II. Adagio III. Andantino con variazioni—Andante The June 15 concert is sponsored by Ralph Muller. The June 16 concert is sponsored by John McFadden and Lisa Kabnick. 24 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra Philadelphia is home and orchestra, and maximizes is one of the preeminent the Orchestra continues impact through Research. orchestras in the world, to discover new and The Orchestra’s award- renowned for its distinctive inventive ways to nurture winning Collaborative sound, desired for its its relationship with its Learning programs engage keen ability to capture the loyal patrons at its home over 50,000 students, hearts and imaginations of in the Kimmel Center, families, and community audiences, and admired for and also with those who members through programs a legacy of imagination and enjoy the Orchestra’s area such as PlayINs, side-by- innovation on and off the performances at the Mann sides, PopUP concerts, concert stage. The Orchestra Center, Penn’s Landing, free Neighborhood is inspiring the future and and other cultural, civic, Concerts, School Concerts, transforming its rich tradition and learning venues. The and residency work in of achievement, sustaining Orchestra maintains a Philadelphia and abroad. the highest level of artistic strong commitment to Through concerts, tours, quality, but also challenging— collaborations with cultural residencies, presentations, and exceeding—that level, and community organizations and recordings, the on a regional and national by creating powerful musical Orchestra is a global cultural level, all of which create experiences for audiences at ambassador for Philadelphia greater access and home and around the world. -

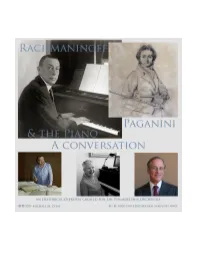

Rachmaninoff, Paganini, & the Piano; a Conversation

Rachmaninoff, Paganini, & the Piano; a Conversation Tracks and clips 1. Rachmaninoff in Paris 16:08 a. Niccolò Paganini, 24 Caprices for Solo Violin, Op. 1, Michael Rabin, EMI 724356799820, recorded 9/5/1958. b. Sergey Rachmaninoff (SR), Rapsodie sur un theme de Paganini, Op. 43, SR, Leopold Stokowski, Philadelphia Orchestra (PO), BMG Classics 09026-61658, recorded 12/24/1934 (PR). c. Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin (FC), Twelve Études, Op. 25, Alfred Cortot, Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft (DGG) 456751, recorded 7/1935. d. SR, Piano Concerto No. 3 in d, Op. 30, SR, Eugene Ormandy (EO), PO, Naxos 8.110601, recorded 12/4/1939.* e. Carl Maria von Weber, Rondo Brillante in E♭, J. 252, Julian Jabobson, Meridian CDE 84251, released 1993.† f. FC, Twelve Études, Op. 25, Ruth Slenczynska (RS), Musical Heritage Society MHS 3798, released 1978. g. SR, Preludes, Op. 32, RS, Ivory Classics 64405-70902, recorded 4/8/1984. h. Georges Enesco, Cello & Piano Sonata, Op. 26 No. 2, Alexandre Dmitriev, Alexandre Paley, Saphir Productions LVC1170, released 10/29/2012.† i. Claude Deubssy, Children’s Corner Suite, L. 113, Walter Gieseking, Dante 167, recorded 1937. j. Ibid., but SR, Victor B-24193, recorded 4/2/1921, TvJ35-zZa-I. ‡ k. SR, Piano Concerto No. 3 in d, Op. 30, Walter Gieseking, John Barbirolli, Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra, Music & Arts MACD 1095, recorded 2/1939.† l. SR, Preludes, Op. 23, RS, Ivory Classics 64405-70902, recorded 4/8/1984. 2. Rachmaninoff & Paganini 6:08 a. Niccolò Paganini, op. cit. b. PR. c. Arcangelo Corelli, Violin Sonata in d, Op. 5 No. 12, Pavlo Beznosiuk, Linn CKD 412, recorded 1/11/2012.♢ d. -

Program Notes | Yannick and Manny

23 Season 2018-2019 Thursday, November 29, at 7:30 The Philadelphia Orchestra Friday, November 30, at 8:00 Saturday, December 1, Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor at 8:00 Emanuel Ax Piano Brahms Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat major, Op. 83 I. Allegro non troppo II. Allegro appassionato III. Andante—Più adagio—Tempo I IV. Allegretto grazioso—Un poco più presto Intermission Brown Perspectives United States premiere Dvořák Symphony No. 7 in D minor, Op. 70 I. Allegro maestoso II. Poco adagio III. Scherzo: Vivace IV. Finale: Allegro This program runs approximately 2 hours, 5 minutes. The November 29 concert is sponsored by Elia D. Buck and Caroline B. Rogers. The November 29 concert is also sponsored by the Louis N. Cassett Foundation. The November 30 concert is sponsored by Alexandra Edsall and Robert Victor. The December 1 concert is sponsored by Medcomp. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM, and are repeated on Monday evenings at 7 PM on WRTI HD 2. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 24 Please join us following the November 30 and December 1 concerts for a free Organ Postlude featuring Peter Richard Conte. Brahms Prelude, from Prelude and Fugue in G minor Brahms Fugue in A-flat minor Dvořák/transcr. Conte Humoresque, Op. 101, No. 7 Widor Toccata, from Organ Symphony No. 5 in F minor, Op. 42, No. 1 The Organ Postludes are part of the Fred J. Cooper Memorial Organ Experience, supported through a generous grant from the Wyncote Foundation. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season

// BOSTON T /?, SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA THURSDAY B SERIES EIGHTY-SEVENTH SEASON 1967-1968 wgm _«9M wsBt Exquisite Sound From the palace of ancient Egyp to the concert hal of our moder cities, the wondroi music of the harp hi compelled attentio from all peoples and a countries. Through th passage of time man changes have been mac in the original design. Tl early instruments shown i drawings on the tomb < Rameses II (1292-1225 B.C were richly decorated bv lacked the fore-pillar. Lato the "Kinner" developed by tl Hebrews took the form as m know it today. The pedal hai was invented about 1720 by Bavarian named Hochbrucker an through this ingenious device it b came possible to play in eight maj< and five minor scales complete. Tods the harp is an important and familij instrument providing the "Exquisi* Sound" and special effects so importai to modern orchestration and arrang ment. The certainty of change mak< necessary a continuous review of yoi insurance protection. We welcome tl opportunity of providing this service f< your business or personal needs. We respectfully invite your inquiry CHARLES H. WATKINS & CO. Richard P. Nyquist — Charles G. Carleton 147 Milk Street Boston, Massachusetts Telephone 542-1250 OBRION, RUSSELL & CO. Insurance of Every Description EIGHTY-SEVENTH SEASON 1967-1968 BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ERICH LEINSDORF Music Director CHARLES WILSON Assistant Conductor THE TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. HENRY B. CABOT President TALCOTT M. BANKS Vice-President JOHN L. THORNDIKE Treasurer PHILIP K. ALLEN E. MORTON JENNINGS JR ABRAM BERKOWITZ EDWARD M. KENNEDY THEODORE P. -

2020-21 Season Brochure

2020 SEA- This year. This season. This orchestra. This music director. Our This performance. This artist. World This moment. This breath. This breath. 2021 SON This breath. Don’t blink. ThePhiladelphiaOrchestra MUSIC DIRECTOR YANNICK NÉZET-SÉGUIN our world Ours is a world divided. And yet, night after night, live music brings audiences together, gifting them with a shared experience. This season, Music Director Yannick Nézet-Séguin and The Philadelphia Orchestra invite you to experience the transformative power of fellowship through a bold exploration of sound. 2 2020–21 Season 3 “For me, music is more than an art form. It’s an artistic force connecting us to each other and to the world around us. I love that our concerts create a space for people to gather as a community—to explore and experience an incredible spectrum of music. Sometimes, we spend an evening in the concert hall together, and it’s simply some hours of joy and beauty. Other times there may be an additional purpose, music in dialogue with an issue or an idea, maybe historic or current, or even a thought that is still not fully formed in our minds and hearts. What’s wonderful is that music gives voice to ideas and feelings that words alone do not; it touches all aspects of our being. Music inspires us to reflect deeply, and music brings us great joy, and so much more. In the end, music connects us more deeply to Our World NOW.” —Yannick Nézet-Séguin 4 2020–21 Season 5 philorch.org / 215.893.1955 6A Thursday Yannick Leads Return to Brahms and Ravel Favorites the Academy Garrick Ohlsson Thursday, October 1 / 7:30 PM Thursday, January 21 / 7:30 PM Thursday, March 25 / 7:30 PM Academy of Music, Philadelphia Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Michael Tilson Thomas Conductor Lisa Batiashvili Violin Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Garrick Ohlsson Piano Hai-Ye Ni Cello Westminster Symphonic Choir Ravel Le Tombeau de Couperin Joe Miller Director Szymanowski Violin Concerto No. -

Season 20 Season 2011-2012

Season 2020111111----2020202011112222 The Philadelphia Orchestra Thursday, March 888,8, at 8:00 Friday, March 999,9, at 222:002:00:00:00 Saturday, March 101010,10 , at 8:00 James Gaffigan Conductor Stewart Goodyear Piano Bernstein Symphonic Suite from On the Waterfront Gershwin/orch. Grofé Rhapsody in Blue Intermission Tchaikovsky Excerpts from Swan Lake, Op. 20 I. Scene II. Waltz III. Dance of the Swans IV. Scene V. Hungarian Dance, Czardas VI. Spanish Dance VII. Neapolitan Dance VIII. Mazurka IX. Scene X. Dance of the Little Swans XI. Scene XII. Final Scene This program runs approximately 1 hour, 50 minutes. American conductor James Gaffigan, who is making his Philadelphia Orchestra debut with these performances, was recently appointed chief conductor of the Lucerne Symphony and principal guest conductor of the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic; he assumed both posts in the summer of 2011. This season he debuts with the Atlanta Symphony and the Los Angeles Philharmonic and makes return visits to the Minnesota Orchestra and the Baltimore, Dallas, Milwaukee, National, and Toronto symphonies. Recent and upcoming festival appearances include the Aspen, Blossom, Grant Park, and Grand Teton music festivals, and the Spoleto Festival USA. In Europe he makes debuts with the Czech, Dresden, and London philharmonics. In 2009 Mr. Gaffigan completed his three-year tenure as associate conductor with the San Francisco Symphony. Prior to that appointment he was assistant conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra. He has appeared with such North American orchestras as the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra and the Chicago, Detroit, Houston, New World, Seattle, and Saint Louis symphonies. -

Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-7-2018 12:30 PM Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse Renee MacKenzie The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Nolan, Catherine The University of Western Ontario Sylvestre, Stéphan The University of Western Ontario Kinton, Leslie The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Music A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Musical Arts © Renee MacKenzie 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation MacKenzie, Renee, "Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse" (2018). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5572. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5572 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This monograph examines the post-exile, multi-version works of Sergei Rachmaninoff with a view to unravelling the sophisticated web of meanings and values attached to them. Compositional revision is an important and complex aspect of creating musical meaning. Considering revision offers an important perspective on the construction and circulation of meanings and discourses attending Rachmaninoff’s music. While Rachmaninoff achieved international recognition during the 1890s as a distinctively Russian musician, I argue that Rachmaninoff’s return to certain compositions through revision played a crucial role in the creation of a narrative and set of tropes representing “Russian diaspora” following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. -

'Anna Karenina Principle' to Better Understand and Operate Family Offices

Using the ‘Anna Karenina principle’ to better understand and operate family offices FAMILY OFFICE AND HIGH NET WORTH “If you’ve seen one family office, you’ve seen one family office.” This is a common refrain in the family office space. are predictable and sometimes preventable. In other But this dogma does the family office world a major words, like the happy families in Anna Karenina, the disservice. The sentiment behind the notion points to most successful family offices tend to adopt similar the individuality of every family. However, taking the pathways to solve problems, as well as optimize their phrase at face value can be counterproductive and operations and service delivery. lead to suboptimal advice and outcomes for families. The purpose of this article is to propose a universal, While family offices often spend an inordinate amount working definition of “family office,” a term whose of time and resources maintaining their privacy, they are ambiguity has led to inefficient communication across neither unique (nor uniquely incomprehensible) entities generations, between families and family offices, and that defy evaluation. While each family office is designed between family offices and their advisors. Sometimes around the needs of its principals, best practices do just hearing “family office” will start to generate exist and can be “fitted” to unique circumstances. So, associations for individuals affiliated with a family it is actually quite possible for families to leverage best office. But if those associations don’t come close practices and proven methods to optimize their family to matching an individual’s experience with family office and produce superior results. -

![Anna Karenina the Truth of Stories “ How Glorious Fall the Valiant, Sword [Mallet] in Hand, in Front of Battle for Their Native Land.” —Tyrtaeus, Spartan Poet the St](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5886/anna-karenina-the-truth-of-stories-how-glorious-fall-the-valiant-sword-mallet-in-hand-in-front-of-battle-for-their-native-land-tyrtaeus-spartan-poet-the-st-435886.webp)

Anna Karenina the Truth of Stories “ How Glorious Fall the Valiant, Sword [Mallet] in Hand, in Front of Battle for Their Native Land.” —Tyrtaeus, Spartan Poet the St

The CollegeSUMMER 2014 • ST. JOHN’S COLLEGE • ANNAPOLIS • SANTA FE Anna Karenina The Truth of Stories “ How glorious fall the valiant, sword [mallet] in hand, in front of battle for their native land.” —Tyrtaeus, Spartan poet The St. John’s croquet team greets the cheering crowd in Annapolis. ii | The College | st. john’s college | summer 2014 from the editor The College is published by St. John’s College, Annapolis, MD, Why Stories? and Santa Fe, NM [email protected] “ He stepped down, trying not to is not just the suspense, but the connection made Known office of publication: through storytelling that matters: “Storytelling Communications Office look long at her, as if she were ought to be done by people who want to make St. John’s College the sun, yet he saw her, like the other people feel a little bit less alone.” 60 College Avenue In this issue we meet Johnnies who are story- Annapolis, MD 21401 sun, even without looking.” tellers in modern and ancient forms, filmmakers, Periodicals postage paid Leo Tolstoy, ANNA KARENINA poets, even a fabric artist. N. Scott Momaday, at Annapolis, MD Pulitzer Prize winner and artist-in-residence on Postmaster: Send address “Emotions are what pull us in—the character’s the Santa Fe campus, says, “Poetry is the high- changes to The College vulnerabilities, desires, and fears,” says screen- est expression of language.” Along with student Magazine, Communications writer Jeremy Leven (A64); he is one of several poets, he shares insights on this elegant form Office, St. John’s College, 60 College Avenue, alumni profiled in this issue of The College who and how it touches our spirits and hearts. -

Seattle Symphony October 2017 Encore

OCTOBER 2017 LUDOVIC MORLOT, MUSIC DIRECTOR BEATRICE RANA PLAYS PROKOFIEV GIDON KREMER SCHUMANN VIOLIN CONCERTO LOOKING AHEAD: MORLOT C O N D U C T S BERLIOZ CONTENTS My wealth. My priorities. My partner. You’ve spent your life accumulating wealth. And, no doubt, that wealth now takes many forms, sits in many places, and is managed by many advisors. Unfortunately, that kind of fragmentation creates gaps that can hold your wealth back from its full potential. The Private Bank can help. The Private Bank uses a proprietary approach called the LIFE Wealth Cycle SM to ind those gaps—and help you achieve what is important to you. To learn more, please visit unionbank.com/theprivatebank or contact: Lisa Roberts Managing Director, Private Wealth Management [email protected] 4157057159 Wills, trusts, foundations, and wealth planning strategies have legal, tax, accounting, and other implications. Clients should consult a legal or tax advisor. ©2017 MUFG Union Bank, N.A. All rights reserved. Member FDIC. Union Bank is a registered trademark and brand name of MUFG Union Bank, N.A. EAP full-page template.indd 1 7/17/17 3:08 PM CONTENTS OCTOBER 2017 4 / CALENDAR 6 / THE SYMPHONY 10 / NEWS FEATURES 12 / BERLIOZ’S BARGAIN 14 / MUSIC & IMAGINATION CONCERTS 15 / October 5 & 7 ENIGMA VARIATIONS 19 / October 6 ELGAR UNTUXED 21 / October 12 & 14 GIDON KREMER SCHUMANN VIOLIN CONCERTO 24 / October 13 [UNTITLED] 1 26 / October 17 NOSFERATU: A SYMPHONY OF HORROR 27 / October 20, 21 & 27 VIVALDI FOUR SEASONS 30 / October 26 & 29 21 / GIDON KREMER SHOSTAKOVICH SYMPHONY NO. -

The Mariinsky Ballet & Orchestra

Thursday, October 1, 2015, 8pm Friday, October 2, 2015, 8pm Saturday, October 3, 2015, 2pm & 8pm Sunday, October 4, 2015, 3pm Zellerbach Hall The Mariinsky Ballet & Orchestra Gavriel Heine, Conductor The Company Diana Vishneva, Nadezhda Batoeva, Anastasia Matvienko, Sofia Gumerova, Ekaterina Chebykina, Kristina Shapran, Elena Bazhenova Vladimir Shklyarov, Konstantin Zverev, Yury Smekalov, Filipp Stepin, Islom Baimuradov, Andrey Yakovlev, Soslan Kulaev, Dmitry Pukhachov Alexandra Somova, Ekaterina Ivannikova, Tamara Gimadieva, Sofia Ivanova-Soblikova, Irina Prokofieva, Anastasia Zaklinskaya, Yuliana Chereshkevich, Lubov Kozharskaya, Yulia Kobzar, Viktoria Brileva, Alisa Krasovskaya, Marina Teterina, Darina Zarubskaya, Olga Gromova, Margarita Frolova, Anna Tolmacheva, Anastasiya Sogrina, Yana Yaschenko, Maria Lebedeva, Alisa Petrenko, Elizaveta Antonova, Alisa Boyarko, Daria Ustyuzhanina, Alexandra Dementieva, Olga Belik, Anastasia Petushkova, Anastasia Mikheikina, Olga Minina, Ksenia Tagunova, Yana Tikhonova, Elena Androsova, Svetlana Ivanova, Ksenia Dubrovina, Ksenia Ostreikovskaya, Diana Smirnova, Renata Shakirova, Alisa Rusina, Ekaterina Krasyuk, Svetlana Russkikh, Irina Tolchilschikova Alexey Popov, Maxim Petrov, Roman Belyakov, Vasily Tkachenko, Andrey Soloviev, Konstantin Ivkin, Alexander Beloborodov, Viktor Litvinenko, Andrey Arseniev, Alexey Atamanov, Nail Enikeev, Vitaly Amelishko, Nikita Lyaschenko, Daniil Lopatin, Yaroslav Baibordin, Evgeny Konovalov, Dmitry Sharapov, Vadim Belyaev, Oleg Demchenko, Alexey Kuzmin, Anatoly Marchenko, -

Troika.Pdf (128.9

TROIKA ALEKO, MISERLY KNIGHT, FRANCESCA DA RIMINI Composer: SERGEI RACHMANINOV ALEKO Librettist: VLADIMIR NEMIROVICH DANCHENKO, AFTER THE GYPSIES, ALEXANDER PUSHKIN Musical version: BOLSHOI THEATER, MOSKVA, 27/4/1893 Piano Score: BOOSEY & HAWKES Orchestra Score: BOOSEY & HAWKES THE MISERLY KNIGHT Librettist: ALEXANDER PUSHKIN Musical version: BOLSHOI THEATER, MOSKVA, 11/1/1906 Piano score: EDITION RUSSE DE MUSIQUE VIA B & H Orchestra score: EDITION RUSSE DE MUSIQUE VIA B & H FRANCESCA DA RIMINI Librettist: MODEST TCHAIKOVSKY AFTER DANTE Musical version: BOLSHOI THEATER, MOSKVA, 11/1/1906 Piano score: BOOSEY & HAWKES Orchestra score: BOOSEY & HAWKES Timing: 1H/50MIN/1H – 3H40 INCLUDING 2 INTERMISSIONS Production by: THÉÂTRE ROYAL DE LAMONNAIE-DEMUNT Season: 2014/2015 Storage: BRUSSELS Premièred at Théâtre National for LaMonnaie-DeMunt on 16 June 2015 sets destroyed ; costumes and video available for rent and sale ARTISTIC TEAM Conductor: MIKHAIL TATARNIKOV Stage director: KIRSTEN DEHLHOLM (Hotel pro Forma) Co-director: JON R. SKULBERG Sets: MAJA ZISKA Costumes: MANON KÜNDIG Lighting: JESPER KONGSHAUG Video: MAGNUS PIND BJERRE Dramaturg: KRYSTIAN LADA CAST Aleko Principals: ♂:3 ♀:2 Chorus: ♂:22 ♀:18 The Miserly knight Principals: ♂:5 Chorus: 0 Francesca da Rimini Principals: ♂:4 ♀:1 Chorus: ♂:22 ♀:18 SCENERY/PROPS Number oF containers: 1 For costumes ORCHESTRA COSTUMES & MAKE UP Violin I: 12 Aleko Violin II: 11 Aleko: 1 Alto: 8 Young gipsy: 1 Cello: 7 Old gipsy: 1 Contrabass: 5 ZemFira: 1 Flute: 3 Gipsy woman: 1 Oboe: 3 Chorus: ♂:22 ♀:18