Tim Buck, the Party, and the People, 1932-1939 John Manley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capitalism Unchallenged : a Sketch of Canadian Communism, 1939 - 1949

CAPITALISM UNCHALLENGED : A SKETCH OF CANADIAN COMMUNISM, 1939 - 1949 Donald William Muldoon B.A., Simon Fraser University, 1974 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History @ DONALD WILLIAM MULDOON 1977 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY February 1977 All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Donald William Muldoon Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: Capitalism Unchallenged : A Sketch of Canadian Communism, 1939 - 1949. Examining Committee8 ., Chair~ergan: .. * ,,. Mike Fellman I Dr. J. Martin Kitchen senid; Supervisor . - Dr.- --in Fisher - &r. Ivan Avakumovic Professor of History University of British Columbia PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis or dissertation (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for mu1 tiple copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesi s/Di ssertation : Author : (signature) (name) (date) ABSTRACT The decade following the outbreak of war in September 1939 was a remarkable one for the Communist Party of Canada and its successor the Labor Progressive Party. -

· by Leslie Morris

e ommun1sts .· By Leslie Morris Sc / Puolished by Progress Books, for the Communist Party of Canada, April, 1961. - You can oJ>tain extra copies of this booklet, at • · 5 for 25 cents, postpaid, from :erogress Books, 44 Stafford St., Toronto, Ontario. THE Founding Convention of the New Party will be held in Ottawa at t·he end o,f July, 1961. It will be one of the mo,st important meetin·gs ever to be held in Canada and much will depend on t·he de:cisions taken there. · Already the Tories, Liberals and Social Crediters are preparing to fi:ght and defeat the New. Party in the coming federal election. The Li1b·erals have held a federal convention in which they tro·tted out a whole bagful of tricks designed to hea1d o.ff 'Suppo·rt for the New Party. T·he Tories held their natio;nal rally a few wee,ks later and John Diefen baker de·clared, in an attempt to· falsify the issues and scare a 1way potential supporters 0 1f the New Party, that ''so·cialism versus freel enterprise'' will be the issue in the election. The Social Credit government of B.C. has passed a vicious piece of legislation prohibiting unions · from ,.. making contri1butions to the Nevi Party on penalty of losing the check-off. Lo·ng be·f ore the election is. anno·unced the lines are bein,g sharply drawn. No matter what differences the To·ries, Liberals and So·cial Crediters have 1between themselves, on one thin1g they are united: the' New Party must be defeated. -

438 the Depression Years. Part I Royal Canadian

438 THE DEPRESSION YEARS. PART I ROYAL CANADIAN MOUNTED POLICE HEADQUARTERS Ottawa, 12th December, 1934. SECRET NO. 736 WEEKLY SUMMARY REPORT ON REVOLUTIONARY ORGANIZATIONS AND ACTTATORS IN CANADA Report It is likely that the success of Tim Buck's big meeting in Toronto will induce the Communists to capitalise Buck and send him out on tour as a means of raising money. The relief workers' strike in Calgary and the farmers' strike in the Vegreville District continue but show signs of breaking up. The [>€ deletion: 3/4 line] in Montreal proposes to publish a new newspaper to be called La Tribune. [2] APPENDTCRS Table of Contents APPENDIX NO. I: GENERAL Paragraph No. 1. Tim Buck at Maple Leaf Gardens, Toronto Large Meeting Held 2-12-34 J. B. Salsberg. A. E. Smith, Stewart Smith, Mrs. E. Morton, Leslie Morris, John Boychuk, Tom Ewen, Sam Carr, Tom Montague, Bill Kashton. Big attendance. Generous collection. 2. [>s deletion: 3 lines] Work Among Unemployed APPENDIX NO. II: REPORTS BY PROVINCRS 3. BRITISH COLUMBIA [>s deletion: 4 lines] The Provincial Workers Council DECEMBER 1934 439 4. ALBERTA Tim Buck Is Expected in Calgary The Murray Mine at East Coulee Won't Recognize M.W.U.C. 5. MANITOBA The W.E.L. in Winnipeg 5th Anniversary, Polish Labour Temple W. Dutkiewicz 6. ONTARIO Tom Hill Anniversary Celebration in Finland, Ont. Furniture Workers Industrial Union Wants Trade Relations Resumed with U.S.S.R. Victor Valin and Reggie Ranton Jugo Slav Clubs Hold Conference District Bureau Elected The Worker Comments on E. Windsor Elections 7. -

APRIL 2015 CURRICULUM VITAE MARKOVITS, Andrei Steven Department of Political Science the University of Michigan 5700 Haven H

APRIL 2015 CURRICULUM VITAE MARKOVITS, Andrei Steven Department of Political Science The University of Michigan 5700 Haven Hall 505 South State Street Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1045 Telephone: (734) 764-6313 Fax: (734) 764-3522 E-mail: [email protected] Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures The University of Michigan 3110 Modern Language Building 812 East Washington Street Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1275 Telephone: (734) 764-8018 Fax: (734) 763-6557 E-mail: [email protected] Date of Birth: October 6, 1948 Place of Birth: Timisoara, Romania Citizenship: U.S.A. Recipient of the Bundesverdienstkreuz Erster Klasse, the Cross of the Order of Merit, First Class, the highest civilian honor bestowed by the Federal Republic of Germany on a civilian, German or foreign; awarded on behalf of the President of the Federal Republic of Germany by the Consul General of the Federal Republic of Germany at the General Consulate of the Federal Republic of Germany in Chicago, Illinois; March 14, 2012. PRESENT FACULTY POSITIONS Arthur F. Thurnau Professor Karl W. Deutsch Collegiate Professor of Comparative Politics and German Studies; Professor of Political Science; Professor of Germanic Languages and Literatures; and Professor of Sociology The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor FORMER FULL-TIME FACULTY POSITIONS Professor of Politics Department of Politics University of California, Santa Cruz July 1, 1992 - June 30, 1999 Chair of the Department of Politics University of California, Santa Cruz July 1, 1992 - June 30, 1995 Associate Professor of Political Science Department of Political Science Boston University July 1, 1983- June 30, 1992 Assistant Professor of Political Science Department of Government Wesleyan University July 1, 1977- June 30, 1983 Research Associate Center for European Studies Harvard University July 1, 1975 - June 30, 1999 EDUCATION Honorary Doctorate Dr. -

Cdunercovenant Winter, 1979

CDunerCOVENANT Winter, 1979 Table of Contents 4 Letters From the Presidents 7 Statement of Purpose 8 A God-directed Faculty 9 Students With Purpose 12 The Facility 13 Stewardship 13 The PCA and Covenant College 15 Administration and Board of Trustees Covenant College discriminates against no one in regard to sex, handicaps, race, ethnic or national origin. 7-78: a landmark year for Covenant College. It was a year of record enrollment, of record giving ... a year of build· truction and campus develo ar whe a new denomination oward joint governance of the precedented growth. It was also sition from one president to another. us in reviewing this year of abundant Looking back over the past year has the greatest meaning in the cont xt of the previous thirteen year . Covenant College moved to Lookout Mountain in 1964 with 145 students, a large hotel to be renovated, 27 acres of land and a mountain ized mortgage. Cov nant College stand today a a great witness to the vitality of the Christian faith and God's faithfulness. It stand b cause of the continuous support and hard work of many great and generous people-friends, faculty, taff, tru tees, student and churches. The college has h Id firm to th faith on which it was founded. It grew and prospered during th turbulent i ties and early seventies. The a sets were increased from $425,475 to $2,875,000. Major new building - library, dormitory, physical education, and now the chapel-fine art --have been added to land holdings now totaling more than 1,000 acres. -

Kenny, (Robert S.) Ms

KENNY, (ROBERT S.) MS. COLL. • 179 Scope The Collection is divided into two parts: 1. Manuscript Extensive and diverse in its attempt to include all aspects of radicalism in Canada, this collection contains material on: a) Communist Party of Canada, including rare leaflets and ephemera b) Tim Buck, A.E. Smith and other Canadian Communists c) A small number of anti-Communist documents and leaflets, as well as information on various Communist trials and the persecution of alleged Communists d) Organizations connected with radicalism and/or Communism in Canada, including briefs written by them to government agencies e) Trade unions f) Relief Camp Strike, B.C., 1935, including leaflets, bulletins and scrapbook. g) Leaflets, some issued by the Communist Party of Canada (including its May Day leaflets); others by various organizations on such topics as peace, Viet Nam, • Quebec nationalism, etc. h) Articles, including drafts of those submitted to the National Affairs Monthly, and translations and reprints chiefly from Russian publications i) Photographs, sound recordings, newspaper clippings, political posters, union medals, campaign ephemera 2. Printed Includes books, pamphlets, broadsides and periodicals reflecting radicalism throughout Canada's history including the Rebellions of 1838 and 1839, Riel Rebellion, Winnipeg General Strike of 1919, the Doukhobours, Quebec nationalism, trade unionism, etc. There are a number of books and pamphlets by Canadian Communist leaders such as Tim Buck, Leslie Morris, as well as pamphlets issued by various political groups including the Communist Party of Canada and the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation. There are complete runs of the National Affairs Monthly, the Marxist quarterly and New frontiers, as well as many broken runs and isolated issues of other left-wing periodicals. -

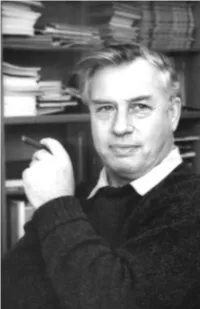

Champagne and Meatballs: Adventures of a Canadian Communist by Bert Whyte, Edited and with an Introduction by Larry Hannant

Champagne_and_Meatballs_Interior.indd 1 11/01/11 1:45 PM Whyte in his prime, cigar at the ready, in Moscow, about 1968 Champagne_and_Meatballs_Interior.indd 2 11/01/11 1:45 PM Champagne and Meatballs Champagne_and_Meatballs_Interior.indd 3 11/01/11 1:45 PM Working Canadians: Books from the CCLH Series editors: Alvin Finkel and Greg Kealey The Canadian Committee on Labour History is Canada’s or- ganization of historians and other scholars interested in the study of the lives and struggles of working people throughout Canada’s past. Since 1976, the CCLH has published Labour/Le travail, Canada’s pre-eminent scholarly journal of labour stud- ies. It also publishes books, now in conjunction with AU Press, that focus on the history of Canada’s working people and their organizations. The emphasis in this series is on materials that are accessible to labour audiences as well as university audi- ences rather than simply on scholarly studies in the labour area. This includes documentary collections, oral histories, auto biographies, bio graphies, and provincial and local labour movement histories with a popular bent. Series Titles Champagne and Meatballs: Adventures of a Canadian Communist by Bert Whyte, edited and with an introduction by Larry Hannant Champagne_and_Meatballs_Interior.indd 4 11/01/11 1:45 PM Champagne and MEATBALLS ADVENTURES of a CANADIAN COMMUNIST Bert Whyte edited and with an introduction by Larry Hannant Canadian Committee on Labour History Champagne_and_Meatballs_Interior.indd 5 11/01/11 1:45 PM © 2011 Larry Hannant Published by AU Press, Athabasca University 1200, 10011–109 Street Edmonton, AB T5J 3S8 Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Whyte, Bert, 1909–1984 Champagne and meatballs : adventures of a Canadian communist / Bert Whyte ; edited and with an introduction by Larry Hannant. -

Frank and Libbie Park Fonds

Manuscript Division des Division manuscrits FRANK AND LIBBIE PARK FONDS MG 31-K9 Finding Aid No. 1194 / Instrument de recherche no 1194 Prepared in 1979 by Tom Nesmith of the Préparé en 1979 par Tom Nesmith des Social and Cultural Archives and revised in Archives sociales et culturelles et revisé en 1982 by Colleen Dempsey and in 2000 by 1982 par Colleen Dempsey et en 2000 par Richard Doré. Richard Doré. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Major Subject Categories Business Structure / The Power and the Money, Anatomy of Big Business ............................................................1 Canada: Land of Two Nations ....................................................5 Canadian Youth Congress .......................................................6 Civil Liberties ................................................................6 Congress of Canadian Women ....................................................8 Eastern Europe................................................................8 Fellowship for a Christian Social Order ............................................8 Korean War ..................................................................9 Labor Movement...........................................................9, 24 Labor-Progressive Party / Communist Party of Canada ............................10, 27 Marxist Studies ..............................................................12 Media......................................................................12 Methodist Federation for Social Action ............................................12 -

A Noble Cause Betrayed…

Research Report No. 64 A Noble Cause Betrayed... but Hope Lives On Pages from a Political Life: Memoirs of a Former Ukrainian Canadian Communist by John Boyd Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press University of Alberta Edmonton 1999 Occasional Research Reports Copies of CIUS Press research reports may be ordered from the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, 352 Athabasca Hall, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 2E8. The name of the publication series and the substantive material in each issue (unless otherwise noted) are copyrighted by the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press. ISBN 1-894301-64-1 PRINTED IN CANADA Occasional Research Reports A Noble Cause Betrayed... but Hope Lives On Pages from a Political Life: Memoirs of a Former Ukrainian Canadian Communist by John Boyd Research Report No. 64 Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press University of Alberta Edmonton 1999 Contents Part 1: My 38 Years (1930-1968) of Working Full Time in the Communist Movement 7 Part 2: Why I Left the Communist Party (My Letter to the Central Executive Committee) 43 Part 3: More Questions about Ukraine and Ukrainians 46 Part 4: My Reply to the Denunciatory Statement of the AUUC National Executive Committee 64 Part 5: More Questions about the Communist Party 68 Part 6: My Report on the 1968 Events in Czechoslovakia 72 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.org/details/noblecausebetray64boyd Preface The following pages are in lieu of a political autobiography. They are, in fact, an edited and upgraded transcript of a series of interviews I gave at the end of 1996 as part of a nation-wide project sponsored by the Cecil-Ross Society. -

Communist Party of Canada Fonds (F0290)

York University Archives & Special Collections (CTASC) Finding Aid - Communist Party of Canada fonds (F0290) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.4.0 Printed: June 27, 2018 Language of description: English York University Archives & Special Collections (CTASC) 305 Scott Library, 4700 Keele Street, York University Toronto Ontario Canada M3J 1P3 Telephone: 416-736-5442 Fax: 416-650-8039 Email: [email protected] http://www.library.yorku.ca/ccm/ArchivesSpecialCollections/index.htm https://atom.library.yorku.ca//index.php/communist-party-of-canada-fonds Communist Party of Canada fonds Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative history / Biographical sketch .................................................................................................. 3 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Access points ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Collection holdings ......................................................................................................................................... -

Class Struggle, the Communist Party and The

CLASS STRUGGLE, THE COMMUNIST PARTY, AND THE POPULAR FRONT IN CANADA, 1935-1939 A Thesis Submitted to the Committee on Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Arts and Science TRENT UNIVERSITY Peterborough, Ontario, Canada © Copyright by Martin Schoots-McAlpine, 2016 Canadian and Indigenous Studies M.A. Graduate Program January 2017 ABSTRACT Class Struggle, The Communist Party, and the Popular Front in Canada, 1935-1939 Martin Schoots-McAlpine This thesis is an attempt to provide a critical history of the Communist Party of Canada (CPC) during the Popular Front era, roughly November 1935 to September 1939. This study contains a detailed examination of the various stages of the Popular Front in Canada (the united front, the height of the Popular Front, and the Democratic front), with special attention paid to the CPC’s activities in: the youth movement, the labour movement, the unemployed movement, the peace movement, and the anti-fascist movement. From this I conclude that the implementation of the Popular Front, the transformation of the CPC from a revolutionary party to a bourgeois party, was not a smooth process, but instead was punctuated and resisted by elements within the CPC in what can be considered a process of class struggle internal to the CPC itself. Keywords: Communist Party of Canada, communism, Soviet Union, labour, Popular Front, Great Depression, socialism, Canada ii Acknowledgements I would first like to express my gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Bryan Palmer, for his patience and assistance in writing this thesis. I benefitted greatly from his expertise in the field. -

Markist Review

NOVEMBER-DECEMBER, 1961 MARKIST REVIEW VOL. XVIII (182) TORONTO, CANADA 25 CENTS EVERYTHING FOR THE GOOD OF MAN - Leslie Morris. 3 THE BERLIN CRISIS AND DIEFENBAKER - Nelson Clarke 11 THE SIGNIFICANCE OF AUTOMATION 16 AUTOMATION AND CANADIAN WORKERS - T. D. 20 THE CUBAN WORKERS AND THE REVOLUTION - Blas Roca ... 22 AFRICA'S ANCIENT CULTURES - I. Potekhin 26 THE SLANDER OF DR. BETHUNE - Stanley Linkovich .. 30 REVIEWS. 36 LETTER 43 GREETINGS TO WORLD MARXIST REVIEW. 47 THE BERLIN CRISIS AND DIEFENBAKER Page 11 Announcing the New Marxist Quarterly In order to make possible the publication of more extensive studi'es of Canadtan and world real'ity, the publishers of MAR."XIST REVIEW have come to the conclusion that our present journal should be replaced by a Quarterly. Starting in the Spring (March), 1\962, publication will com mence of the new magazine. THE MARXIST QUARTERLY Of larger format, the new journal wil'l carry creatJive articles on themes of importance in the fields of pol,itical science and economics, social conditions and history, culture and philo'sophy. We are confident that it will carry forward and enlarge on the contribution made by MARXIST REVIEW, in the battle for progressive thought ~n Canada.' It is planned that the MARXIST QUARTERLY be priced at 50 cents: a copy, $2.00 per year. Subscribers td MARXIST REVIEW will be asked to continue as subscribers to the QUARTERLY, and to agree, where there are subscrtption payments extending beyond the present final issue of MR, to have these apply toward a subscription to the Quarterly. The Editorial Board, MARXIST REVIEW -------------r------------- SUBSCRIPTION BLAN'K I RENEWAL BLANK Enelosed please find $2.00 for a year's I Enclosed please find $2.00 to renew my subscription to MARXIST QUARTERLY.