Naming Warhips 1812

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ESPS Santa María Frigate EUNAVFOR Med GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS

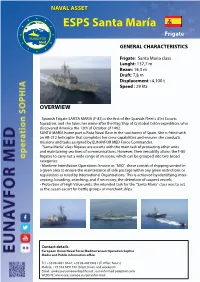

NAVAL ASSET ESPS Santa María Frigate EUNAVFOR Med GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS Frigate: Santa Maria class Lenght: 137,7 m Beam: 14,3 m Draft: 7,8 m Displacement : 4,100 t Speed : 29 kts OVERWIEW Spanish Frigate SANTA MARÍA (F-81) is the first of the Spanish Fleet’s 41st Escorts Squadron, and she takes her name after the Flag Ship of Cristobal Colón expedition, who discovered America the 12th of October of 1492. SANTA MARÍA home port is Rota Naval Base in the southwest of Spain. She is fitted with an AB-212 helicopter that completes her crew capabilities and ensures she conducts missions and tasks assigned by EUNAVFOR MED Force Commander. “Santa María” class frigates are escorts with the main task of protecting other units and maintaining sea lines of communications. However, their versatility allows the F-80 frigates to carry out a wide range of missions, which can be grouped into two broad categories: • Maritime Interdiction Operations: known as “MIO”, these consist of shipping control in a given area to ensure the maintenance of safe passage within any given restrictions or regulations as ruled by International Organisations. This is achieved by identifying, inter- cepting, boarding, searching, and if necessary, the detention of suspect vessels; • Protection of High Value units: the intended task for the “Santa Maria” class was to act as the ocean escort for battle groups or merchant ships. Contact details European Union Naval Force Mediterranean Operation Sophia Media and Public information office Tel: +39 06 4691 9442 ; +39 06 46919451 (IT Office hours) Mobile: +39 334 6891930 (Silent hours and weekend) Email: [email protected] ; [email protected] WEBSITE: www.eeas.europa.eu/eunavfor-med. -

USS CONSTELLATION Page 4 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 USS CONSTELLATION Page 4 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form Summary The USS Constellation’s career in naval service spanned one hundred years: from commissioning on July 28, 1855 at Norfolk Navy Yard, Virginia to final decommissioning on February 4, 1955 at Boston, Massachusetts. (She was moved to Baltimore, Maryland in the summer of 1955.) During that century this sailing sloop-of-war, sometimes termed a “corvette,” was nationally significant for its ante-bellum service, particularly for its role in the effort to end the foreign slave trade. It is also nationally significant as a major resource in the mid-19th century United States Navy representing a technological turning point in the history of U.S. naval architecture. In addition, the USS Constellation is significant for its Civil War activities, its late 19th century missions, and for its unique contribution to international relations both at the close of the 19th century and during World War II. At one time it was believed that Constellation was a 1797 ship contemporary to the frigate Constitution moored in Boston. This led to a long-standing controversy over the actual identity of the Constellation. Maritime scholars long ago reached consensus that the vessel currently moored in Baltimore is the 1850s U.S. navy sloop-of-war, not the earlier 1797 frigate. Describe Present and Historic Physical Appearance. The USS Constellation, now preserved at Baltimore, Maryland, was built at the navy yard at Norfolk, Virginia. -

From Sail to Steam: London's Role in a Shipbuilding Revolution Transcript

From Sail to Steam: London's Role in a Shipbuilding Revolution Transcript Date: Monday, 24 October 2016 - 1:00PM Location: Museum of London 24 October 2016 From Sail to Steam: London’s Role in a Shipbuilding Revolution Elliott Wragg Introduction The almost deserted River Thames of today, plied by pleasure boats and river buses is a far cry from its recent past when London was the greatest port in the world. Today only the remaining docks, largely used as mooring for domestic vessels or for dinghy sailing, give any hint as to this illustrious mercantile heritage. This story, however, is fairly well known. What is less well known is London’s role as a shipbuilder While we instinctively think of Portsmouth, Plymouth and the Clyde as the homes of the Royal Navy, London played at least an equal part as any of these right up until the latter half of the 19th century, and for one brief period was undoubtedly the world’s leading shipbuilder with technological capability and capacity beyond all its rivals. Little physical evidence of these vast enterprises is visible behind the river wall but when the tide goes out the Thames foreshore gives us glimpses of just how much nautical activity took place along its banks. From the remains of abandoned small craft at Brentford and Isleworth to unique hulked vessels at Tripcockness, from long abandoned slipways at Millwall and Deptford to ship-breaking assemblages at Charlton, Rotherhithe and Bermondsey, these tantalising remains are all that are left to remind us of London’s central role in Britain’s maritime story. -

Esps Canarias

European Union Naval Force - Mediterranean ESPS CANARIAS Frigate Santa Maria class Frigate Santa Maria class Length / Beam / Draft 138 m / 14,3 m / 7,5 m Displacement 3,900 t Speed 29 knots (maximum turbine) Source: Spanish Defense website http://www.armada.mde.es The Ship ESPS CANARIAS is the sixth frigate of the 41st Escorts Squadron; she was built by Navantia in Ferrol, and delivered to the Navy in December 1994. ESPS CANARIAS home port is Rota Naval Base in the south of Spain. ESPS CANARIAS is fitted with a helicopter SH-60 and Marine Boarding Team that completes her capabilities and ensures she is capable of conducting the missions and tasks assigned by EUNAVFOR MED. The Santa Maria Class is a multirole warship able to carry out missions ranging from high intensity warfare integrated into a battle group and conducting offensive and defensive operations, to low intensity scenarios against non-conventional threats. Designed primarily to act in the interests of the State in the maritime areas overseas and participate in the settlement crises outside Europe, this leading warship can also be integrated into a naval air force. It may operate in support of an intervention force or protection of commercial traffic and perform special operations or humanitarian missions. The Santa Maria class frigates, like destroyers and corvettes, are given the generic name of escorts with the main task of protecting other units and maintaining sea lines of communications. However, their versatility allows the F-80 frigates to carry out a wide range of missions, which can be grouped into two broad categories: • Maritime Interdiction Operations: known as 'MIO operations', these consist of shipping control in a given area to ensure the maintenance of safe passage within any given restrictions or regulations as ruled by International Organisations. -

Scenes from Aboard the Frigate HMCS Dunver, 1943-1945

Canadian Military History Volume 10 Issue 2 Article 6 2001 Through the Camera’s Lens: Scenes from Aboard the Frigate HMCS Dunver, 1943-1945 Cliff Quince Serge Durflinger University of Ottawa, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Quince, Cliff and Durflinger, Serge "Through the Camera’s Lens: Scenes from Aboard the Frigate HMCS Dunver, 1943-1945." Canadian Military History 10, 2 (2001) This Canadian War Museum is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Quince and Durflinger: Scenes from Aboard the HMCS <em>Dunver</em> Cliff Quince and Serge Durflinger he Battle of the Atlantic was the the ship's unofficial photographer until Tlongest and most important February 1945 at which time the navy maritime campaign of the Second World granted him a formal photographer's War. Germany's large and powerful pass. This pass did not make him an submarine fleet menaced the merchant official RCN photographer, since he vessels carrying the essential supplies maintained all his shipboard duties; it upon which depended the survival of merely enabled him to take photos as Great Britain and, ultimately, the he saw fit. liberation of Western Europe. The campaign was also one of the most vicious and Born in Montreal in 1925, Cliff came by his unforgiving of the war, where little quarter was knack for photography honestly. -

July 2019 Whole No

Dedicated to the Study of Naval and Maritime Covers Vol. 86 No. 7 July 2019 Whole No. 1028 July 2019 IN THIS ISSUE Feature Cover From the Editor’s Desk 2 Send for Your Own Covers 2 Out of the Past 3 Calendar of Events 3 Naval News 4 President’s Message 5 The Goat Locker 6 For Beginning Members 8 West Coast Navy News 9 Norfolk Navy News 10 Chapter News 11 Fleet Week New York 2019 11 USS ARKANSAS (BB 33) 12 2019-2020 Committees 13 Pictorial Cancellations 13 USS SCAMP (SS 277) 14 One Reason Why we Collect 15 Leonhard Venne provided the feature cover for this issue of the USCS Log. His cachet marks the 75th Anniversary of Author-Ship: the D-Day Operations and the cover was cancelled at LT Herman Wouk, USNR 16 Williamsburg, Virginia on 6 JUN 2019. USS NEW MEXICO (BB 40) 17 Story Behind the Cover… 18 Ships Named After USN and USMC Aviators 21 Fantail Forum –Part 8 22 The Chesapeake Raider 24 The Joy of Collecting 27 Auctions 28 Covers for Sale 30 Classified Ads 31 Secretary’s Report 32 Page 2 Universal Ship Cancellation Society Log July 2019 The Universal Ship Cancellation Society, Inc., (APS From the Editor's Desk Affiliate #98), a non-profit, tax exempt corporation, founded in 1932, promotes the study of the history of ships, their postal Midyear and operations at this end seem to markings and postal documentation of events involving the U.S. be back to normal as far as the Log is Navy and other maritime organizations of the world. -

China's Logistics Capabilities for Expeditionary Operations

China’s Logistics Capabilities for Expeditionary Operations The modular transfer system between a Type 054A frigate and a COSCO container ship during China’s first military-civil UNREP. Source: “重大突破!民船为海军水面舰艇实施干货补给 [Breakthrough! Civil Ships Implement Dry Cargo Supply for Naval Surface Ships],” Guancha, November 15, 2019 Primary author: Chad Peltier Supporting analysts: Tate Nurkin and Sean O’Connor Disclaimer: This research report was prepared at the request of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission to support its deliberations. Posting of the report to the Commission's website is intended to promote greater public understanding of the issues addressed by the Commission in its ongoing assessment of U.S.-China economic relations and their implications for U.S. security, as mandated by Public Law 106-398 and Public Law 113-291. However, it does not necessarily imply an endorsement by the Commission or any individual Commissioner of the views or conclusions expressed in this commissioned research report. 1 Contents Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Methodology, Scope, and Study Limitations ........................................................................................................ 6 1. China’s Expeditionary Operations -

The 1812 Streets of Cambridgeport

The 1812 Streets of Cambridgeport The Last Battle of the Revolution Less than a quarter of a century after the close of the American Revolution, Great Britain and the United States were again in conflict. Britain and her allies were engaged in a long war with Napoleonic France. The shipping-related industries of the neutral United States benefited hugely, conducting trade with both sides. Hundreds of ships, built in yards on America’s Atlantic coast and manned by American sailors, carried goods, including foodstuffs and raw materials, to Europe and the West Indies. Merchants and farmers alike reaped the profits. In Cambridge, men made plans to profit from this brisk trade. “[T]he soaring hopes of expansionist-minded promoters and speculators in Cambridge were based solidly on the assumption that the economic future of Cambridge rested on its potential as a shipping center.” The very name, Cambridgeport, reflected “the expectation that several miles of waterfront could be developed into a port with an intricate system of canals.” In January 1805, Congress designated Cambridge as a “port of delivery” and “canal dredging began [and] prices of dock lots soared." [1] Judge Francis Dana, a lawyer, diplomat, and Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, was one of the primary investors in the development of Cambridgeport. He and his large family lived in a handsome mansion on what is now Dana Hill. Dana lost heavily when Jefferson declared an embargo in 1807. Britain and France objected to America’s commercial relationship with their respective enemies and took steps to curtail trade with the United States. -

U.S. Navy Ships-Of-The-Line

U.S. Navy – Ships-of-the-line A Frigate vs A Ship-of-the-Line: What’s the difference? FRIGATE: A vessel of war which is: 1) “ship” rigged, i.e. – with at least three masts (fore, main, & mizzen) & each mast carries the horizontal yards from which the principle sails are set; 2) this “ship-rigged vessel of war” is a FRIGATE because it has one covered, principle gun deck – USS Constitution is therefore a FRIGATE by class (illus. left) SHIP-OF-THE-LINE: A vessel of war which is: 1) “ship” rigged (see above); 2) this “ship-rigged vessel of war” is a SHIP-OF-THE-LINE because it has two or more covered gun decks – HMS Victory is therefore a SHIP-OF-THE-LINE by class (illus. right) HMS Victory (1765); 100+ guns; 820 officers Constitution preparing to battle Guerriere, & crew; oldest commissioned warship in the M.F. Corne, 1812 – PEM Coll. world, permanently dry docked in England Pg. 1 NMM Coll. An Act, 2 January 1813 – for the construction of the U.S. Navy’s first Ships-of-the-line USS Independence was the first ship-of-the-line launched for the USN from the Boston (Charlestown) Navy Yard on 22 June 1814: While rated for 74-guns, Independence was armed with 87 guns when she was launched. USS Washington was launched at the Portsmouth Navy Yard, 1 October 1814 USS Pennsylvania – largest sailing warship built for the USN USS Pennsylvania – rated for 136 guns on three covered gun decks + guns on her upper (spar) deck – the largest sailing warship ever built. -

Dunham Bible Museum Collection Were Produced by the American Bible Society

Bible Museum NewsD unham Houston Baptist University Fall 2016 Volume 14, Issue 1 200 YEARS OF THE ABS May 8, 2016, the American Bible Society (ABS) marked ideas of the Enlightenment and Deism, and wrote Age of its 200th anniversary. The Society grew up with the United Revelation as a reply to Paine’s Age of Reason. Yet, with all States and throughout its 200 year history has played an his accomplishments, Boudinot considered his election important role in Bible distribution and translation. In as President of the American Bible Society as his highest many ways the ABS patterned its activities after the British honor; he donated $10,000 (no mean sum in 1816!) to help and Foreign Bible Society, organized in 1804. A number establish the Society. of local Bible societies had formed in the United States, The American Bible Society was one of the first religious beginning with the Bible Society of Philadelphia in 1808. non-profit organizations in the United States. It was an outgrowth of the Second Great Awakening, the spiritual revival that transformed much of American society in the first half of the nineteenth century. Many notable Americans were part of the Society’s early years. John Jay, first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and signer of the Declaration Elias Boudinot had held of Independence and the Treaty of Paris, became President numerous government of the ABS after Boudinot. Francis Scott Key, author of the positions, including President The Star Spangled Banner, was Vice-President from 1817 to of Congress and Director of the U.S. -

S. C. Shipbuilding in the Age of Sail Carl Naylor University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected]

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Archaeology and Anthropology, South Carolina Faculty & Staff ubP lications Institute of 11-1993 S. C. Shipbuilding In The Age of Sail Carl Naylor University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sciaa_staffpub Part of the Anthropology Commons Publication Info Published in The Goody Bag, Volume 4, Issue 4, 1993, pages 4&8-. http://www.cas.sc.edu/sciaa/ © 1993 by The outhS Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology This Article is brought to you by the Archaeology and Anthropology, South Carolina Institute of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty & Staff ubP lications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Part Three S. C. Shipbuilding In The Age of Sail (Editor's Note: In the first two in while discussing the cost of shipbuild Queenley was registered to trade be stallments of this article we discussed ing in Carolina with William Fisher, a tween Carolina and Georgia. The the beginnings of shipbuilding in colo Philadelphia shipowner, he notes that Queenley was built in 1739 in South nial South Carolina, the spread of ship "The difference in the Cost of our Car0- Carolina, twenty-seven years earlier. building throughout the colony, and the lina built Vessels is not the great objec When the 15-ton schooner Friendship types of vessels being built by South tion to building here. That is made up in was registered for trade in 1773, it was Carolina shipwrights. -

Carter, USN 62Nd Superintendent of the US Naval Academy

Vice Admiral Walter “Ted” Carter, USN 62nd Superintendent of the U.S. Naval Academy Vice Admiral Walter E. “Ted” Carter Jr. became the 62nd superintendent of the U.S. Naval Academy on July 23, 2014. He graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1981, was designated a Naval Flight Officer in 1982, and graduated from the Navy Fighter Weapons School, Top Gun, in 1985. He completed the Air Command and Staff College course and the Armed Forces Staff College. In 2001, he completed the Navy’s Nuclear Power Program. Carter’s career as an aviator includes extensive time at sea, deploying around the globe in the F-4 Phantom II and the F-14 Tomcat. He has landed on 19 different aircraft carriers, to include all 10 of the Nimitz Class carriers. Carter commanded the VF-14 “Tophatters,” served as Executive Officer of USS Harry S. Truman (CVN 75), and commanded both USS Camden (AOE 2) and USS Carl Vinson (CVN 70). His most recent Fleet command assignment was Commander, Enterprise Carrier Strike Group (CSG-12) during Big E’s final combat deployment as a 51 year old aircraft carrier in 2012. Ashore, Carter served as Chief of Staff for Fighter Wing Pacific and Executive Assistant to the Deputy Commander, U.S. Central Command. He served as Commander, Joint Enabling Capabilities Command and subsequently as lead for the Transition Planning Team during the disestablishment of U.S. Joint Forces Command in 2011. After leading Task Force RESILIENT (a study in suicide related behaviors), he established the 21st Century Sailor Office (OPNAV N17) as its first Director in 2013.