Thomas Jefferson, Congress, and the Gunboat Debate, 1802

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

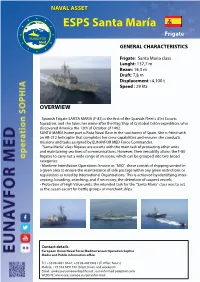

ESPS Santa María Frigate EUNAVFOR Med GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS

NAVAL ASSET ESPS Santa María Frigate EUNAVFOR Med GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS Frigate: Santa Maria class Lenght: 137,7 m Beam: 14,3 m Draft: 7,8 m Displacement : 4,100 t Speed : 29 kts OVERWIEW Spanish Frigate SANTA MARÍA (F-81) is the first of the Spanish Fleet’s 41st Escorts Squadron, and she takes her name after the Flag Ship of Cristobal Colón expedition, who discovered America the 12th of October of 1492. SANTA MARÍA home port is Rota Naval Base in the southwest of Spain. She is fitted with an AB-212 helicopter that completes her crew capabilities and ensures she conducts missions and tasks assigned by EUNAVFOR MED Force Commander. “Santa María” class frigates are escorts with the main task of protecting other units and maintaining sea lines of communications. However, their versatility allows the F-80 frigates to carry out a wide range of missions, which can be grouped into two broad categories: • Maritime Interdiction Operations: known as “MIO”, these consist of shipping control in a given area to ensure the maintenance of safe passage within any given restrictions or regulations as ruled by International Organisations. This is achieved by identifying, inter- cepting, boarding, searching, and if necessary, the detention of suspect vessels; • Protection of High Value units: the intended task for the “Santa Maria” class was to act as the ocean escort for battle groups or merchant ships. Contact details European Union Naval Force Mediterranean Operation Sophia Media and Public information office Tel: +39 06 4691 9442 ; +39 06 46919451 (IT Office hours) Mobile: +39 334 6891930 (Silent hours and weekend) Email: [email protected] ; [email protected] WEBSITE: www.eeas.europa.eu/eunavfor-med. -

USS CONSTELLATION Page 4 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 USS CONSTELLATION Page 4 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form Summary The USS Constellation’s career in naval service spanned one hundred years: from commissioning on July 28, 1855 at Norfolk Navy Yard, Virginia to final decommissioning on February 4, 1955 at Boston, Massachusetts. (She was moved to Baltimore, Maryland in the summer of 1955.) During that century this sailing sloop-of-war, sometimes termed a “corvette,” was nationally significant for its ante-bellum service, particularly for its role in the effort to end the foreign slave trade. It is also nationally significant as a major resource in the mid-19th century United States Navy representing a technological turning point in the history of U.S. naval architecture. In addition, the USS Constellation is significant for its Civil War activities, its late 19th century missions, and for its unique contribution to international relations both at the close of the 19th century and during World War II. At one time it was believed that Constellation was a 1797 ship contemporary to the frigate Constitution moored in Boston. This led to a long-standing controversy over the actual identity of the Constellation. Maritime scholars long ago reached consensus that the vessel currently moored in Baltimore is the 1850s U.S. navy sloop-of-war, not the earlier 1797 frigate. Describe Present and Historic Physical Appearance. The USS Constellation, now preserved at Baltimore, Maryland, was built at the navy yard at Norfolk, Virginia. -

From Sail to Steam: London's Role in a Shipbuilding Revolution Transcript

From Sail to Steam: London's Role in a Shipbuilding Revolution Transcript Date: Monday, 24 October 2016 - 1:00PM Location: Museum of London 24 October 2016 From Sail to Steam: London’s Role in a Shipbuilding Revolution Elliott Wragg Introduction The almost deserted River Thames of today, plied by pleasure boats and river buses is a far cry from its recent past when London was the greatest port in the world. Today only the remaining docks, largely used as mooring for domestic vessels or for dinghy sailing, give any hint as to this illustrious mercantile heritage. This story, however, is fairly well known. What is less well known is London’s role as a shipbuilder While we instinctively think of Portsmouth, Plymouth and the Clyde as the homes of the Royal Navy, London played at least an equal part as any of these right up until the latter half of the 19th century, and for one brief period was undoubtedly the world’s leading shipbuilder with technological capability and capacity beyond all its rivals. Little physical evidence of these vast enterprises is visible behind the river wall but when the tide goes out the Thames foreshore gives us glimpses of just how much nautical activity took place along its banks. From the remains of abandoned small craft at Brentford and Isleworth to unique hulked vessels at Tripcockness, from long abandoned slipways at Millwall and Deptford to ship-breaking assemblages at Charlton, Rotherhithe and Bermondsey, these tantalising remains are all that are left to remind us of London’s central role in Britain’s maritime story. -

Thomas Jefferson and the Ideology of Democratic Schooling

Thomas Jefferson and the Ideology of Democratic Schooling James Carpenter (Binghamton University) Abstract I challenge the traditional argument that Jefferson’s educational plans for Virginia were built on mod- ern democratic understandings. While containing some democratic features, especially for the founding decades, Jefferson’s concern was narrowly political, designed to ensure the survival of the new republic. The significance of this piece is to add to the more accurate portrayal of Jefferson’s impact on American institutions. Submit your own response to this article Submit online at democracyeducationjournal.org/home Read responses to this article online http://democracyeducationjournal.org/home/vol21/iss2/5 ew historical figures have undergone as much advocate of public education in the early United States” (p. 280). scrutiny in the last two decades as has Thomas Heslep (1969) has suggested that Jefferson provided “a general Jefferson. His relationship with Sally Hemings, his statement on education in republican, or democratic society” views on Native Americans, his expansionist ideology and his (p. 113), without distinguishing between the two. Others have opted suppressionF of individual liberties are just some of the areas of specifically to connect his ideas to being democratic. Williams Jefferson’s life and thinking that historians and others have reexam- (1967) argued that Jefferson’s impact on our schools is pronounced ined (Finkelman, 1995; Gordon- Reed, 1997; Kaplan, 1998). because “democracy and education are interdependent” and But his views on education have been unchallenged. While his therefore with “education being necessary to its [democracy’s] reputation as a founding father of the American republic has been success, a successful democracy must provide it” (p. -

Social Life in the Early Republic: a Machine-Readable Transcription

Library of Congress Social life in the early republic vii PREFACE peared to them, or recall the quaint figures of Mrs. Alexander Hamilton and Mrs. Madison in old age, or the younger faces of Cora Livingston, Adèle Cutts, Mrs. Gardiner G. Howland, and Madame de Potestad. To those who have aided her with personal recollections or valuable family papers and letters the author makes grateful acknowledgment, her thanks being especially due to Mrs. Samuel Phillips Lee, Mrs. Beverly Kennon, Mrs. M. E. Donelson Wilcox, Miss Virginia Mason, Mr. James Nourse and the Misses Nourse of the Highlands, to Mrs. Robert K. Stone, Miss Fanny Lee Jones, Mrs. Semple, Mrs. Julia F. Snow, Mr. J. Henley Smith, Mrs. Thompson H. Alexander, Miss Rosa Mordecai, Mrs. Harriot Stoddert Turner, Miss Caroline Miller, Mrs. T. Skipwith Coles, Dr. James Dudley Morgan, and Mr. Charles Washington Coleman. A. H. W. Philadelphia, October, 1902. ix CONTENTS Chapter Page I— A Social Evolution 13 II— A Predestined Capital 42 Social life in the early republic http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbcb.29033 Library of Congress III— Homes and Hostelries 58 IV— County Families 78 V— Jeffersonian Simplicity 102 VI— A Queen of Hearts 131 VII— The Bladensburg Races 161 VII— Peace and Plenty 179 IX— Classics and Cotillions 208 X— A Ladies' Battle 236 XI— Through Several Administrations 267 XII— Mid-Century Gayeties 296 xi ILLUSTRATIONS Page Mrs. Richard Gittings, of Baltimore (Polly Sterett) Frontispiece From portrait by Charles Willson Peale, owned by her great-grandson, Mr. D. Sterett Gittings, of Baltimore. Mrs. Gittings eyes are dark brown, the hair dark brown, with lighter shades through it; the gown of delicate pink, the sleeves caught up with pearls, the sash of a gray shade. -

Federal Libraries/Information Centers Chronology

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS THE FEDERAL LIBRARY AND BICENTENNIAL INFORMATION CENTER 1800 - 2000 COMMITTEE American Federal Libraries/Information Centers Chronology 1780 Military garrison at West Point establishes library by assessing officers at the rate of one day’s pay per month to purchase books—arguably the first federal library since it existed when the country was founded (predecessor to U.S. Military Academy Library) 1789 First official federal library established at the Department of State 1795 War Department Library established in Philadelphia as a general historical military library by Henry Knox, the first Secretary of War 1800 The Navy Department Library established on March 31 by direction of President John Adams to Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddert 1800 Library of Congress (LoC) founded on April 24 1800 War Department Library collections destroyed in fire at War Office Building on November 8, soon after relocation to Washington 1802 The President and Vice President authorized to use LoC collections 1812 Supreme Court Justices authorized to use LoC collections 1812 Congress appropriates $50,000 for the procurement of instruments and books for Coast Survey 1814 British burn both State Department Library and LoC collections during War of 1812 1815 Congress purchases Thomas Jefferson’s private library to replace LoC collections and opens collections to the general public 1817 Earliest documentation of book purchasing for Department of Treasury library 1820 Army Surgeon General James Lovell establishes office collection of books -

By: Jim Rosenberger

April 2016 Wisconsin’s Chapter ~ Interested & Involved Number 58 During this time in history: (August 1804 - January 1807) (The source for all entries is, "The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition edited by Gary E. Moulton, U. of Nebraska Press, 1983- 2001.) Our journal entries deal with the activities of Expedition member Sgt. Patrick Gass. August 26, 1804, in today’s Clay County, 1804- - - - - - By: Jim Rosenberger- - - - - -1806 South Dakota, by order of Captains Lewis & Clark: “The commanding officers have In the almost three years that Lewis and Clark lead the Corps of Discovery other thought it proper to appoint Patrick Gass, a events were taking place in the United States and in the world; events they did Sergeant in the Corps of Volunteers for the not know about until their return trip to St. Louis; events that would affect the North Western Discovery, he is therefore to world and our newly formed nation. The Corps had essentially had no news be obeyed and respected accordingly. Sgt. Gass is directed to take charge of the late since leaving St. Louis in May of 1804 but on September 3, 1806 that changed. Sgt. Floyd’s mess and immediately to enter At a location described by Gary Moulton as “…particularly vague…it would on the discharge of such other duties as, by seem to have been in Union County, South Dakota or Dakota County, Nebraska, their previous orders been prescribed for the some miles up the Missouri (River) from present Sioux City…” the men met government of the sergeants of this corps…” two boats coming up the Missouri River. -

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles The Chinese Navy Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Saunders, EDITED BY Yung, Swaine, PhILLIP C. SAUNderS, ChrISToPher YUNG, and Yang MIChAeL Swaine, ANd ANdreW NIeN-dzU YANG CeNTer For The STUdY oF ChINeSe MilitarY AffairS INSTITUTe For NATIoNAL STrATeGIC STUdIeS NatioNAL deFeNSe UNIverSITY COVER 4 SPINE 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY COVER.indd 3 COVER 1 11/29/11 12:35 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 1 11/29/11 12:37 PM 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 2 11/29/11 12:37 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Edited by Phillip C. Saunders, Christopher D. Yung, Michael Swaine, and Andrew Nien-Dzu Yang Published by National Defense University Press for the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs Institute for National Strategic Studies Washington, D.C. 2011 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 3 11/29/11 12:37 PM Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Defense or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Chapter 5 was originally published as an article of the same title in Asian Security 5, no. 2 (2009), 144–169. Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. Used by permission. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Chinese Navy : expanding capabilities, evolving roles / edited by Phillip C. Saunders ... [et al.]. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Narrative Section of a Successful Application

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the Research Programs application guidelines at http://www.neh.gov/grants/research/scholarly-editions-and-translations-grants for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Research Programs staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson Institution: Princeton University Project Director: Barbara Bowen Oberg Grant Program: Scholarly Editions and Translations 1100 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W., Rm. 318, Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8200 F 202.606.8204 E [email protected] www.neh.gov Statement of Significance and Impact of Project This project is preparing the authoritative edition of the correspondence and papers of Thomas Jefferson. Publication of the first volume of The Papers of Thomas Jefferson in 1950 kindled renewed interest in the nation’s documentary heritage and set new standards for the organization and presentation of historical documents. Its impact has been felt across the humanities, reaching not just scholars of American history, but undergraduate students, high school teachers, journalists, lawyers, and an interested, inquisitive American public. -

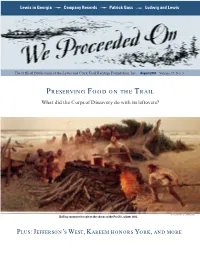

PRESERVING FOOD on the TRAIL What Did the Corps of Discovery Do with Its Leftovers?

Lewis in Georgia Company Records Patrick Gass Ludwig and Lewis The Official Publication of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, Inc. August 2001 Volume 27, No. 3 PRESERVING FOOD ON THE TRAIL What did the Corps of Discovery do with its leftovers? THE SALT MAKERS, BY JOHN CLYMER Boiling seawater for salt on the shores of the Pacific, winter 1806. PLUS: JEFFERSON’S WEST, KAREEM HONORS YORK, AND MORE Contents Letters: Chinook Point; John Ordway; iron boat 2 From the Directors: A special thanks to all 4 Bicentennial Report: Ambrose pledges $1 million 5 Preserving Food on the L&C Expedition 6 What the Corps of Discovery did with its leftovers By Leandra Holland Getting Out the Word 12 Preserving food, p. 6 Patrick Gass’s role in publicizing the expedtion’s return By James J. Holmberg Company Books 18 What they tell us about the Corps of Discovery By Bob Moore Lewis’s Georgia Boyhood 25 His brief but formative sojourn in the Deep South By James P. Hendrix, Jr. Trail Notes: Minimizing impact on Lemhi Pass 29 Reviews: Ronda on Jefferson; the Trail by kayak and mule 30 Jefferson, p. 30 L&C Roundup: Kareem honors York; Chapter News 33 From the Library: New librarian sought 34 Soundings 36 A Lewis & Clark Symphony? By Skip Jackson On the cover We chose The Salt Makers, John Clymer’s dramatic painting of Lewis and Clark’s men making salt under the curious gaze of Pacific Coast Indians, to illustrate Leandra Holland’s story on food preservation (pages 6-11). -

Andrew Hull Foote, Gunboat Commodore

w..:l ~ w 0 r:c Qo (:.L..Q r:c 0 (Y) ~OlSSIJr;v, w -- t----:1 ~~ <.D ~ r '"' 0" t----:1 ~~ co ~ll(r~'Sa ~ r--1 w :::JO ...~ I ' -I~~ ~ ~0 <.D ~~if z E--t 0 y ~& ~ co oQ" t----:1 ~~ r--1 :t.z-~3NNO'l ............. t----:1 w..:l~ ~ o::z z0Q~ ~ CONNECTICUT CIVIL WAR CENTENNIAL COMMISSION • ALBERT D. PUTNAM, Chairman WILLIAM J. FINAN, Vice Chairman WILLIAM J. LoWRY, Secretary ALBERT D. PUTNAM (CHAJRMAN) .. ......................... Hartf01'd HAMILTON BAsso .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ...... .. Westport PRoF. HAROLD J. BINGHAM ................................... New Britain lHOMAs J. CALDWELL ............................................ Rocky Hill J. DoYLE DEWITT ............................................ West Hartford RoBERT EISENBERG .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Stratford WILLIAM J. FINAN ..................................................... W oodmont DANIEL I. FLETCHER . ........ ... ..... .. ... .... ....... .. ... Hartf01'd BENEDICT M. HoLDEN, JR. ................................ W est Hartford ALLAN KELLER . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Darien MRs. EsTHER B. LINDQUIST .................................. ......... Gltilford WILLIAM J. LoWRY .. .......................................... Wethersfield DR. WM. J. MAsSIE ............................................. New Haven WILLIAM E. MILLs, JR. ........................ ,....... ......... ........ Stamford EDwARD OLSEN .............................. .............. .. ..... Westbrook. -

Jefferson's Failed Anti-Slavery Priviso of 1784 and the Nascence of Free Soil Constitutionalism

MERKEL_FINAL 4/3/2008 9:41:47 AM Jefferson’s Failed Anti-Slavery Proviso of 1784 and the Nascence of Free Soil Constitutionalism William G. Merkel∗ ABSTRACT Despite his severe racism and inextricable personal commit- ments to slavery, Thomas Jefferson made profoundly significant con- tributions to the rise of anti-slavery constitutionalism. This Article examines the narrowly defeated anti-slavery plank in the Territorial Governance Act drafted by Jefferson and ratified by Congress in 1784. The provision would have prohibited slavery in all new states carved out of the western territories ceded to the national government estab- lished under the Articles of Confederation. The Act set out the prin- ciple that new states would be admitted to the Union on equal terms with existing members, and provided the blueprint for the Republi- can Guarantee Clause and prohibitions against titles of nobility in the United States Constitution of 1788. The defeated anti-slavery plank inspired the anti-slavery proviso successfully passed into law with the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. Unlike that Ordinance’s famous anti- slavery clause, Jefferson’s defeated provision would have applied south as well as north of the Ohio River. ∗ Associate Professor of Law, Washburn University; D. Phil., University of Ox- ford, (History); J.D., Columbia University. Thanks to Sarah Barringer Gordon, Thomas Grey, and Larry Kramer for insightful comment and critique at the Yale/Stanford Junior Faculty Forum in June 2006. The paper benefited greatly from probing questions by members of the University of Kansas and Washburn Law facul- ties at faculty lunches. Colin Bonwick, Richard Carwardine, Michael Dorf, Daniel W.