Why Are Ice and Snow Important to Us?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

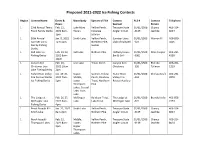

Proposed 2021-2022 Ice Fishing Contests

Proposed 2021-2022 Ice Fishing Contests Region Contest Name Dates & Waterbody Species of Fish Contest ALS # Contact Telephone Hours Sponsor Person 1 23rd Annual Teena Feb. 12, Lake Mary Yellow Perch, Treasure State 01/01/1500 Chancy 406-314- Frank Family Derby 2022 6am- Ronan Kokanee Angler Circuit -3139 Jeschke 8024 1pm Salmon 1 50th Annual Jan. 8, 2022 Smith Lake Yellow Perch, Sunriser Lions 01/01/1500 Warren Illi 406-890- Sunriser Lions 7am-1pm Northern Pike, Club of Kalispell -323 0205 Family Fishing Sucker Derby 1 Bull Lake Ice Feb. 19-20, Bull Lake Nothern Pike Halfway House 01/01/1500 Dave Cooper 406-295- Fishing Derby 2022 6am- Bar & Grill -3061 4358 10pm 1 Canyon Kid Feb. 26, Lion Lake Trout, Perch Canyon Kids 01/01/1500 Rhonda 406-261- Christmas Lion 2022 10am- Christmas -326 Tallman 1219 Lake Fishing Derby 2pm 1 Fisher River Valley Jan. 29-30, Upper, Salmon, Yellow Fisher River 01/01/1500 Chelsea Kraft 406-291- Fire Rescue Winter 2022 7am- Middle, Perch, Rainbow Valley Fire -324 2870 Ice Fishing Derby 5pm Lower Trout, Northern Rescue Auxilary Thompson Pike Lakes, Crystal Lake, Loon Lake 1 The Lodge at Feb. 26-27, McGregor Rainbow Trout, The Lodge at 01/01/1500 Brandy Kiefer 406-858- McGregor Lake 2022 6am- Lake Lake Trout McGregor Lake -322 2253 Fishing Derby 4pm 1 Perch Assault #2- Jan. 22, 2022 Smith Lake Yellow Perch, Treasure State 01/01/1500 Chancy 406-314- Smith Lake 8am-2pm Nothern Pike Angler Circuit -3139 Jeschke 8024 1 Perch Assault- Feb. -

Effects of Ice Formation on Hydrology and Water Quality in the Lower Bradley River, Alaska Implications for Salmon Incubation Habitat

ruses science for a changing world Prepared in cooperation with the Alaska Energy Authority u Effects of Ice Formation on Hydrology and Water Quality in the Lower Bradley River, Alaska Implications for Salmon Incubation Habitat Water-Resources Investigations Report 98-4191 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover photograph: Ice pedestals at Bradley River near Tidewater transect, February 28, 1995. Effects of Ice Formation on Hydrology and Water Quality in the Lower Bradley River, Alaska Implications for Salmon Incubation Habitat by Ronald L. Rickman U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 98-4191 Prepared in cooperation with the ALASKA ENERGY AUTHORITY Anchorage, Alaska 1998 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas J. Casadevall, Acting Director Use of trade names in this report is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. For additional information: Copies of this report may be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services 4230 University Drive, Suite 201 Box 25286 Anchorage, AK 99508-4664 Denver, CO 80225-0286 http://www-water-ak.usgs.gov CONTENTS Abstract ................................................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................... 1 Location of Study Area.................................................. 1 Bradley Lake Hydroelectric Project ....................................... -

“Mining” Water Ice on Mars an Assessment of ISRU Options in Support of Future Human Missions

National Aeronautics and Space Administration “Mining” Water Ice on Mars An Assessment of ISRU Options in Support of Future Human Missions Stephen Hoffman, Alida Andrews, Kevin Watts July 2016 Agenda • Introduction • What kind of water ice are we talking about • Options for accessing the water ice • Drilling Options • “Mining” Options • EMC scenario and requirements • Recommendations and future work Acknowledgement • The authors of this report learned much during the process of researching the technologies and operations associated with drilling into icy deposits and extract water from those deposits. We would like to acknowledge the support and advice provided by the following individuals and their organizations: – Brian Glass, PhD, NASA Ames Research Center – Robert Haehnel, PhD, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers/Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory – Patrick Haggerty, National Science Foundation/Geosciences/Polar Programs – Jennifer Mercer, PhD, National Science Foundation/Geosciences/Polar Programs – Frank Rack, PhD, University of Nebraska-Lincoln – Jason Weale, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers/Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory Mining Water Ice on Mars INTRODUCTION Background • Addendum to M-WIP study, addressing one of the areas not fully covered in this report: accessing and mining water ice if it is present in certain glacier-like forms – The M-WIP report is available at http://mepag.nasa.gov/reports.cfm • The First Landing Site/Exploration Zone Workshop for Human Missions to Mars (October 2015) set the target -

Systems Approach to Management of Water Resources—Toward Performance Based Water Resources Engineering

water Article Systems Approach to Management of Water Resources—Toward Performance Based Water Resources Engineering Slobodan P. Simonovic Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, The University of Western Ontario, London, ON N6A 5B9, Canada; [email protected]; Tel.: +1-519-661-4075 Received: 29 March 2020; Accepted: 20 April 2020; Published: 24 April 2020 Abstract: Global change, that results from population growth, global warming and land use change (especially rapid urbanization), is directly affecting the complexity of water resources management problems and the uncertainty to which they are exposed. Both, the complexity and the uncertainty, are the result of dynamic interactions between multiple system elements within three major systems: (i) the physical environment; (ii) the social environment; and (iii) the constructed infrastructure environment including pipes, roads, bridges, buildings, and other components. Recent trends in dealing with complex water resources systems include consideration of the whole region being affected, explicit incorporation of all costs and benefits, development of a large number of alternative solutions, and the active (early) involvement of all stakeholders in the decision-making. Systems approaches based on simulation, optimization, and multi-objective analyses, in deterministic, stochastic and fuzzy forms, have demonstrated in the last half of last century, a great success in supporting effective water resources management. This paper explores the future opportunities that will utilize advancements in systems theory that might transform management of water resources on a broader scale. The paper presents performance-based water resources engineering as a methodological framework to extend the role of the systems approach in improved sustainable water resources management under changing conditions (with special consideration given to rapid climate destabilization). -

The Modelling of Freezing Process in Saturated Soil Based on the Thermal-Hydro-Mechanical Multi-Physics Field Coupling Theory

water Article The Modelling of Freezing Process in Saturated Soil Based on the Thermal-Hydro-Mechanical Multi-Physics Field Coupling Theory Dawei Lei 1,2, Yugui Yang 1,2,* , Chengzheng Cai 1,2, Yong Chen 3 and Songhe Wang 4 1 State Key Laboratory for Geomechanics and Deep Underground Engineering, China University of Mining and Technology, Xuzhou 221008, China; [email protected] (D.L.); [email protected] (C.C.) 2 School of Mechanics and Civil Engineering, China University of Mining and Technology, Xuzhou 221116, China 3 State Key Laboratory of Coal Resource and Safe Mining, China University of Mining and Technology, Xuzhou 221116, China; [email protected] 4 Institute of Geotechnical Engineering, Xi’an University of Technology, Xi’an 710048, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 2 September 2020; Accepted: 22 September 2020; Published: 25 September 2020 Abstract: The freezing process of saturated soil is studied under the condition of water replenishment. The process of soil freezing was simulated based on the theory of the energy and mass conservation equations and the equation of mechanical equilibrium. The accuracy of the model was verified by comparison with the experimental results of soil freezing. One-side freezing of a saturated 10-cm-high soil column in an open system with different parameters was simulated, and the effects of the initial void ratio, hydraulic conductivity, and thermal conductivity of soil particles on soil frost heave, freezing depth, and ice lenses distribution during soil freezing were explored. During the freezing process, water migrates from the warm end to the frozen fringe under the actions of the temperature gradient and pore pressure. -

Chapter 7 Seasonal Snow Cover, Ice and Permafrost

I Chapter 7 Seasonal snow cover, ice and permafrost Co-Chairmen: R.B. Street, Canada P.I. Melnikov, USSR Expert contributors: D. Riseborough (Canada); O. Anisimov (USSR); Cheng Guodong (China); V.J. Lunardini (USA); M. Gavrilova (USSR); E.A. Köster (The Netherlands); R.M. Koerner (Canada); M.F. Meier (USA); M. Smith (Canada); H. Baker (Canada); N.A. Grave (USSR); CM. Clapperton (UK); M. Brugman (Canada); S.M. Hodge (USA); L. Menchaca (Mexico); A.S. Judge (Canada); P.G. Quilty (Australia); R.Hansson (Norway); J.A. Heginbottom (Canada); H. Keys (New Zealand); D.A. Etkin (Canada); F.E. Nelson (USA); D.M. Barnett (Canada); B. Fitzharris (New Zealand); I.M. Whillans (USA); A.A. Velichko (USSR); R. Haugen (USA); F. Sayles (USA); Contents 1 Introduction 7-1 2 Environmental impacts 7-2 2.1 Seasonal snow cover 7-2 2.2 Ice sheets and glaciers 7-4 2.3 Permafrost 7-7 2.3.1 Nature, extent and stability of permafrost 7-7 2.3.2 Responses of permafrost to climatic changes 7-10 2.3.2.1 Changes in permafrost distribution 7-12 2.3.2.2 Implications of permafrost degradation 7-14 2.3.3 Gas hydrates and methane 7-15 2.4 Seasonally frozen ground 7-16 3 Socioeconomic consequences 7-16 3.1 Seasonal snow cover 7-16 3.2 Glaciers and ice sheets 7-17 3.3 Permafrost 7-18 3.4 Seasonally frozen ground 7-22 4 Future deliberations 7-22 Tables Table 7.1 Relative extent of terrestrial areas of seasonal snow cover, ice and permafrost (after Washburn, 1980a and Rott, 1983) 7-2 Table 7.2 Characteristics of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets (based on Oerlemans and van der Veen, 1984) 7-5 Table 7.3 Effect of terrestrial ice sheets on sea-level, adapted from Workshop on Glaciers, Ice Sheets and Sea Level: Effect of a COylnduced Climatic Change. -

Freshwater Resources

3 Freshwater Resources Coordinating Lead Authors: Blanca E. Jiménez Cisneros (Mexico), Taikan Oki (Japan) Lead Authors: Nigel W. Arnell (UK), Gerardo Benito (Spain), J. Graham Cogley (Canada), Petra Döll (Germany), Tong Jiang (China), Shadrack S. Mwakalila (Tanzania) Contributing Authors: Thomas Fischer (Germany), Dieter Gerten (Germany), Regine Hock (Canada), Shinjiro Kanae (Japan), Xixi Lu (Singapore), Luis José Mata (Venezuela), Claudia Pahl-Wostl (Germany), Kenneth M. Strzepek (USA), Buda Su (China), B. van den Hurk (Netherlands) Review Editor: Zbigniew Kundzewicz (Poland) Volunteer Chapter Scientist: Asako Nishijima (Japan) This chapter should be cited as: Jiménez Cisneros , B.E., T. Oki, N.W. Arnell, G. Benito, J.G. Cogley, P. Döll, T. Jiang, and S.S. Mwakalila, 2014: Freshwater resources. In: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Field, C.B., V.R. Barros, D.J. Dokken, K.J. Mach, M.D. Mastrandrea, T.E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K.L. Ebi, Y.O. Estrada, R.C. Genova, B. Girma, E.S. Kissel, A.N. Levy, S. MacCracken, P.R. Mastrandrea, and L.L. White (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 229-269. 229 Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................................ 232 3.1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................... -

Remote Sensing of Sea Ice

Remote Sensing of Sea Ice Peter Lemke Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research Bremerhaven Institute for Environmental Physics University of Bremen Contents 1. Ice and climate 2. Sea Ice Properties 3. Remote Sensing Techniques Contents 1. Ice and climate 2. Sea Ice Properties 3. Remote Sensing Techniques The Cryosphere Area Volume Volume [106 km2] [106 km3] [relativ] Ice Sheets 14.8 28.8 600 Ice Shelves 1.4 0.5 10 Sea Ice 23.0 0.05 1 Snow 45.0 0.0025 0.05 Climate System vHigh albedo vLatent heat vPlastic material Role of Ice in Climate v Impact on surface energy balance (global sink) ! Atmospheric circulation ! Oceanic circulation ! Polar amplification v Impact on gas exchange between the atmosphere and Earth’s surface v Impact on water cycle, water supply v Impact on sea level (ice mass imbalance) v Defines boundary conditions for ecosystems Role of Ice in Climate v Polar amplification in CO2 warming scenarios (surface energy balance; temperature – ice albedo feedback) IPCC, 2007 Role of Ice in Climate Polar amplification GFDL model 12 IPCC AR4 models Warming from CO2 doubling with Warming at CO2 doubling (years fixed albedo (FA) and with surface 61-80) (Winton, 2006) albedo feedback included (VA) (Hall, 2004) Contents 1. Ice and climate 2. Sea Ice Properties 3. Remote Sensing Techniques Pancake Ice Pancake Ice Old Pancake Ice First Year Ice Pressure Ridges Pressure Ridges New Ice Formation in Leads New Ice Formation in Leads New Ice Formation in Leads Melt Ponds on Arctic Sea Ice Melt ponds in the Arctic 150 m Sediment -

Integrated Planning and Management at Community Level

Training manual Water resource management: Integrated planning and management at community level This training manual is intended to help to WaterAid in Nepal ’s partners and stakeholders train community leaders in developing integrated plans for managing water resource at community level. The production of this manual was led by Kabir Das Rajbhandari from WaterAid in Nepal with support from WaterAid in Nepal ’s partners. Consultant Dinesh Raj Manandhar assisted in the preparation of this manual by organising a series of workshops at community level and with practitioners. Colleagues from the Advocacy team in Nepal reviewed the document, providing valuable input. This document should be cited as WaterAid in Nepal (2011) Training manual - Water resource management: Integrated planning and management at community level. The document can be found in the documents section of the WaterAid in Nepal country programme website– www.nepal.wateraid.org A WaterAid in Nepal publication September 2011 WaterAid transforms lives by improving access to safe water, hygiene and sanitation in the world’s poorest communities. We work with partners and influence decision makers to maximise our impact. Cover picture: Top: A school girl at Lalit Kalyan School behind recharged well from harvested rain. WaterAid/ Anita Pradhan Middle: Pratima Shakya from Hakha tole in Lalitpur district at the dug well front to her house. Bottom: Krishna Shrestha caretaker, Sunga wastewater treatment plant, Thimee. WaterAid/ Marco Betti Contents Abbreviation iii 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 WaterAid and Water Resource Management (WRM) 2 1.3 CWRM approach and capacity building 4 1.4 About the manual 5 1.5 Target group 6 1.6 Objective of the training 6 1.7 Expected outcomes 6 2. -

East Antarctic Sea Ice in Spring: Spectral Albedo of Snow, Nilas, Frost Flowers and Slush, and Light-Absorbing Impurities in Snow

Annals of Glaciology 56(69) 2015 doi: 10.3189/2015AoG69A574 53 East Antarctic sea ice in spring: spectral albedo of snow, nilas, frost flowers and slush, and light-absorbing impurities in snow Maria C. ZATKO, Stephen G. WARREN Department of Atmospheric Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT. Spectral albedos of open water, nilas, nilas with frost flowers, slush, and first-year ice with both thin and thick snow cover were measured in the East Antarctic sea-ice zone during the Sea Ice Physics and Ecosystems eXperiment II (SIPEX II) from September to November 2012, near 658 S, 1208 E. Albedo was measured across the ultraviolet (UV), visible and near-infrared (nIR) wavelengths, augmenting a dataset from prior Antarctic expeditions with spectral coverage extended to longer wavelengths, and with measurement of slush and frost flowers, which had not been encountered on the prior expeditions. At visible and UV wavelengths, the albedo depends on the thickness of snow or ice; in the nIR the albedo is determined by the specific surface area. The growth of frost flowers causes the nilas albedo to increase by 0.2±0.3 in the UV and visible wavelengths. The spectral albedos are integrated over wavelength to obtain broadband albedos for wavelength bands commonly used in climate models. The albedo spectrum for deep snow on first-year sea ice shows no evidence of light- absorbing particulate impurities (LAI), such as black carbon (BC) or organics, which is consistent with the extremely small quantities of LAI found by filtering snow meltwater. -

Ice Energy & Our Ice Batteries

Efficiency and Reliability – A Win/Win for Utilities and Consumers Ice Energy & Our Ice Batteries Greg Miller EVP Market Development & Sales [email protected], 970-227-9406 Discover the Power of Ice Ice Energy Mission Transforming Air Conditioning, which is the Principal Driver and Root Cause of Peak Demand driving the Highest Energy Cost Periods of the Day/Season, Into a Clean, Flexible and Reliable Energy Storage Resource for Utilities and Consumers, Enabling Energy Consumption Pattern Changes Automatically without Cooling Sacrifice Utility and Consumer Use Case Example: . Southern California Edison Ice Bear Program (Orange County) . Installing 1800 Ice Bears at commercial & industrial buildings to reduce 26 MW of HVAC peak load from 2 pm to 6 pm every day without cooling sacrifice . Utility objective is to reduce SCE substation energy constraints for Johanna and Santiago substations . Opportunity for consumers is to permanently reduce HVAC peak load and shift HVAC energy consumption to night time periods saving thousands of dollar with little to no investment – includes 20 years free Ice Bear annual maintenance Energy Storage: Barriers for Some, Advantages for Ice Major Competitive Advantage Lowest cost, longest lasting battery on the market, most environmental friendly battery using Water/Ice as energy storage media Extremely reliable 98%+ availability over 35 million operating hours, 1400+ units deployed to date, 14 years in business Environmentally Friendly & Safe No fire and no use of chemical – storage media is water. No -

Sharing the Road with the Environment: Road Salt Pollution

Sharing the Road with the Environment EPA’s Stormwater Pollution Prevention Webinar Series: Road Salt Pollution Prevention Strategies January 31, 2013 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency Brooke Asleson WHAT’S THE PROBLEM? Finding a Balance between Safe Roads and Clean Water Problem Chloride is toxic to aquatic life and once in our waters there is no feasible way to remove it Road Salt (~75%) is primary source of Chloride in Twin Cities Metropolitan Area (TCMA), 25% is from other sources such as Wastewater Treatment Plants (water softening) University of Minnesota study found that 78% of the chloride applied is being retained in the TCMA 365,000* tons of road salt are applied in TCMA each year *this is an estimate based on purchasing records The Public expects & needs safe roads, parking lots and sidewalks Path to Achieving Balance (Safe Roads + Clean Water) Water Quality Impacts & Conditions Understand Implement Road Safety Needs Develop Create a Shared Goals Shared Vision & Strategies What Is Being Done? Understand Current Water Quality Conditions Developing Partnerships- Building a Shared Vision/Common Goals Level 1 Certification: Snow & Ice Control Best Practices TCMA Chloride Management Plan project ◦ Monitoring, Partnerships with stakeholders, Significant outreach efforts,TMDLs MPCA draft MS4 permit requires covered storage of road salt MPCA NPDES “Salty Discharges” being required to monitor for Chloride Chloride Criteria Water Quality Standard ◦ 230mg/L Chronic, 860 mg/L Acute ◦ 1 teaspoon of salt pollutes 5 gallons of