The Modelling of Freezing Process in Saturated Soil Based on the Thermal-Hydro-Mechanical Multi-Physics Field Coupling Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

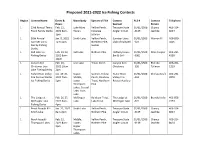

Proposed 2021-2022 Ice Fishing Contests

Proposed 2021-2022 Ice Fishing Contests Region Contest Name Dates & Waterbody Species of Fish Contest ALS # Contact Telephone Hours Sponsor Person 1 23rd Annual Teena Feb. 12, Lake Mary Yellow Perch, Treasure State 01/01/1500 Chancy 406-314- Frank Family Derby 2022 6am- Ronan Kokanee Angler Circuit -3139 Jeschke 8024 1pm Salmon 1 50th Annual Jan. 8, 2022 Smith Lake Yellow Perch, Sunriser Lions 01/01/1500 Warren Illi 406-890- Sunriser Lions 7am-1pm Northern Pike, Club of Kalispell -323 0205 Family Fishing Sucker Derby 1 Bull Lake Ice Feb. 19-20, Bull Lake Nothern Pike Halfway House 01/01/1500 Dave Cooper 406-295- Fishing Derby 2022 6am- Bar & Grill -3061 4358 10pm 1 Canyon Kid Feb. 26, Lion Lake Trout, Perch Canyon Kids 01/01/1500 Rhonda 406-261- Christmas Lion 2022 10am- Christmas -326 Tallman 1219 Lake Fishing Derby 2pm 1 Fisher River Valley Jan. 29-30, Upper, Salmon, Yellow Fisher River 01/01/1500 Chelsea Kraft 406-291- Fire Rescue Winter 2022 7am- Middle, Perch, Rainbow Valley Fire -324 2870 Ice Fishing Derby 5pm Lower Trout, Northern Rescue Auxilary Thompson Pike Lakes, Crystal Lake, Loon Lake 1 The Lodge at Feb. 26-27, McGregor Rainbow Trout, The Lodge at 01/01/1500 Brandy Kiefer 406-858- McGregor Lake 2022 6am- Lake Lake Trout McGregor Lake -322 2253 Fishing Derby 4pm 1 Perch Assault #2- Jan. 22, 2022 Smith Lake Yellow Perch, Treasure State 01/01/1500 Chancy 406-314- Smith Lake 8am-2pm Nothern Pike Angler Circuit -3139 Jeschke 8024 1 Perch Assault- Feb. -

Effects of Ice Formation on Hydrology and Water Quality in the Lower Bradley River, Alaska Implications for Salmon Incubation Habitat

ruses science for a changing world Prepared in cooperation with the Alaska Energy Authority u Effects of Ice Formation on Hydrology and Water Quality in the Lower Bradley River, Alaska Implications for Salmon Incubation Habitat Water-Resources Investigations Report 98-4191 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover photograph: Ice pedestals at Bradley River near Tidewater transect, February 28, 1995. Effects of Ice Formation on Hydrology and Water Quality in the Lower Bradley River, Alaska Implications for Salmon Incubation Habitat by Ronald L. Rickman U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 98-4191 Prepared in cooperation with the ALASKA ENERGY AUTHORITY Anchorage, Alaska 1998 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas J. Casadevall, Acting Director Use of trade names in this report is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. For additional information: Copies of this report may be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services 4230 University Drive, Suite 201 Box 25286 Anchorage, AK 99508-4664 Denver, CO 80225-0286 http://www-water-ak.usgs.gov CONTENTS Abstract ................................................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................... 1 Location of Study Area.................................................. 1 Bradley Lake Hydroelectric Project ....................................... -

A Study of Unstable Slopes in Permafrost Areas: Alaskan Case Studies Used As a Training Tool

A Study of Unstable Slopes in Permafrost Areas: Alaskan Case Studies Used as a Training Tool Item Type Report Authors Darrow, Margaret M.; Huang, Scott L.; Obermiller, Kyle Publisher Alaska University Transportation Center Download date 26/09/2021 04:55:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/7546 A Study of Unstable Slopes in Permafrost Areas: Alaskan Case Studies Used as a Training Tool Final Report December 2011 Prepared by PI: Margaret M. Darrow, Ph.D. Co-PI: Scott L. Huang, Ph.D. Co-author: Kyle Obermiller Institute of Northern Engineering for Alaska University Transportation Center REPORT CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 1 2.0 REVIEW OF UNSTABLE SOIL SLOPES IN PERMAFROST AREAS ............................... 1 3.0 THE NELCHINA SLIDE ..................................................................................................... 2 4.0 THE RICH113 SLIDE ......................................................................................................... 5 5.0 THE CHITINA DUMP SLIDE .............................................................................................. 6 6.0 SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................... 9 7.0 REFERENCES ................................................................................................................. 10 i A STUDY OF UNSTABLE SLOPES IN PERMAFROST AREAS 1.0 INTRODUCTION -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Molards as an indicator of permafrost degradation and landslide processes Journal Item How to cite: Morino, Costanza; Conway, Susan J.; Sæmundsson, Þorsteinn; Kristinn Helgason, Jón; Hillier, John; Butcher, Frances E.G.; Balme, Matthew R.; Jordan, Colm and Argles, Tom (2019). Molards as an indicator of permafrost degradation and landslide processes. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 516 pp. 136–147. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2019 Elsevier B.V. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2019.03.040 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Earth and Planetary Science Letters 516 (2019) 136–147 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth and Planetary Science Letters www.elsevier.com/locate/epsl Molards as an indicator of permafrost degradation and landslide processes ∗ Costanza Morino a,b, , Susan J. Conway b, Þorsteinn Sæmundsson c, Jón Kristinn Helgason d, John Hillier e, Frances E.G. Butcher f, Matthew R. Balme f, Colm Jordan g, Tom Argles a a School of Environment, Earth & Ecosystem Sciences, The Open University, Walton Hall, Milton Keynes, MK7 6AA, UK b Laboratoire de Planétologie et Géodynamique -

The Distribution of Silty Soils in the Grayling Fingers Region of Michigan: Evidence for Loess Deposition Onto Frozen Ground

Geomorphology 102 (2008) 287–296 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Geomorphology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/geomorph The distribution of silty soils in the Grayling Fingers region of Michigan: Evidence for loess deposition onto frozen ground Randall J. Schaetzl ⁎ Department of Geography, 128 Geography Building, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, 48824-1117, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: This paper presents textural, geochemical, mineralogical, soils, and geomorphic data on the sediments of the Received 12 September 2007 Grayling Fingers region of northern Lower Michigan. The Fingers are mainly comprised of glaciofluvial Received in revised form 25 March 2008 sediment, capped by sandy till. The focus of this research is a thin silty cap that overlies the till and outwash; Accepted 26 March 2008 data presented here suggest that it is local-source loess, derived from the Port Huron outwash plain and its Available online 10 April 2008 down-river extension, the Mainstee River valley. The silt is geochemically and texturally unlike the glacial fl Keywords: sediments that underlie it and is located only on the attest parts of the Finger uplands and in the bottoms of Glacial geomorphology upland, dry kettles. On sloping sites, the silty cap is absent. The silt was probably deposited on the Fingers Loess during the Port Huron meltwater event; a loess deposit roughly 90 km down the Manistee River valley has a Permafrost comparable origin. Data suggest that the loess was only able to persist on upland surfaces that were either Kettles closed depressions (currently, dry kettles) or flat because of erosion during and after loess deposition. -

“Mining” Water Ice on Mars an Assessment of ISRU Options in Support of Future Human Missions

National Aeronautics and Space Administration “Mining” Water Ice on Mars An Assessment of ISRU Options in Support of Future Human Missions Stephen Hoffman, Alida Andrews, Kevin Watts July 2016 Agenda • Introduction • What kind of water ice are we talking about • Options for accessing the water ice • Drilling Options • “Mining” Options • EMC scenario and requirements • Recommendations and future work Acknowledgement • The authors of this report learned much during the process of researching the technologies and operations associated with drilling into icy deposits and extract water from those deposits. We would like to acknowledge the support and advice provided by the following individuals and their organizations: – Brian Glass, PhD, NASA Ames Research Center – Robert Haehnel, PhD, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers/Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory – Patrick Haggerty, National Science Foundation/Geosciences/Polar Programs – Jennifer Mercer, PhD, National Science Foundation/Geosciences/Polar Programs – Frank Rack, PhD, University of Nebraska-Lincoln – Jason Weale, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers/Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory Mining Water Ice on Mars INTRODUCTION Background • Addendum to M-WIP study, addressing one of the areas not fully covered in this report: accessing and mining water ice if it is present in certain glacier-like forms – The M-WIP report is available at http://mepag.nasa.gov/reports.cfm • The First Landing Site/Exploration Zone Workshop for Human Missions to Mars (October 2015) set the target -

Cryogenic Displacement and Accumulation of Biogenic Methane in Frozen Soils

atmosphere Article Cryogenic Displacement and Accumulation of Biogenic Methane in Frozen Soils Gleb Kraev 1,*, Ernst-Detlef Schulze 2, Alla Yurova 3,4, Alexander Kholodov 5,6, Evgeny Chuvilin 7 and Elizaveta Rivkina 6 1 Centre of Forest Ecology and Productivity, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow 117997, Russia 2 Department of Biogeochemical Processes, Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry, Jena 07745, Germany; [email protected] 3 Institute of Earth Sciences, Saint Petersburg State University, Saint Petersburg 199034, Russia; [email protected] 4 Nansen Centre, Saint Petersburg 199034, Russia 5 Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK 99775-9320, USA; [email protected] 6 Institute of Physicochemical and Biological Problems in Soil Science, Russian Academy of Sciences, Pushchino 142290, Russia; [email protected] 7 Faculty of Geology, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow 119992, Russia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +7-499-743-0026 Received: 28 March 2017; Accepted: 9 June 2017; Published: 15 June 2017 Abstract: Evidences of highly localized methane fluxes are reported from the Arctic shelf, hot spots of methane emissions in thermokarst lakes, and are believed to evolve to features like Yamal crater on land. The origin of large methane outbursts is problematic. Here we show, that the biogenic methane (13C ≤ −71 ) which formed before and during soil freezing is presently held in the permafrost. Field and experimentalh observations show that methane tends to accumulate at the permafrost table or in the coarse-grained lithological pockets surrounded by the sediments less-permeable for gas. Our field observations, radiocarbon dating, laboratory tests and theory all suggest that depending on the soil structure and freezing dynamics, this methane may have been displaced downwards tens of meters during freezing and has accumulated in the lithological pockets. -

Systems Approach to Management of Water Resources—Toward Performance Based Water Resources Engineering

water Article Systems Approach to Management of Water Resources—Toward Performance Based Water Resources Engineering Slobodan P. Simonovic Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, The University of Western Ontario, London, ON N6A 5B9, Canada; [email protected]; Tel.: +1-519-661-4075 Received: 29 March 2020; Accepted: 20 April 2020; Published: 24 April 2020 Abstract: Global change, that results from population growth, global warming and land use change (especially rapid urbanization), is directly affecting the complexity of water resources management problems and the uncertainty to which they are exposed. Both, the complexity and the uncertainty, are the result of dynamic interactions between multiple system elements within three major systems: (i) the physical environment; (ii) the social environment; and (iii) the constructed infrastructure environment including pipes, roads, bridges, buildings, and other components. Recent trends in dealing with complex water resources systems include consideration of the whole region being affected, explicit incorporation of all costs and benefits, development of a large number of alternative solutions, and the active (early) involvement of all stakeholders in the decision-making. Systems approaches based on simulation, optimization, and multi-objective analyses, in deterministic, stochastic and fuzzy forms, have demonstrated in the last half of last century, a great success in supporting effective water resources management. This paper explores the future opportunities that will utilize advancements in systems theory that might transform management of water resources on a broader scale. The paper presents performance-based water resources engineering as a methodological framework to extend the role of the systems approach in improved sustainable water resources management under changing conditions (with special consideration given to rapid climate destabilization). -

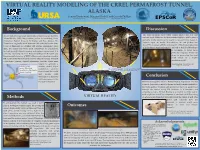

Virtual Reality Modeling of the CRREL Permafrost Tunnel, Alaska

VIRTUAL REALITY MODELING OF THE CRREL PERMAFROST TUNNEL, ALASKA Conner Truskowski, Margaret Rudolf, and Cassidy Phillips [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Background Discussion The main problem faced while taking photos was low and As of today, few real, small-scale locations have been modeled for variable light. While we did have smaller lights to add to what is Virtual Reality (VR). One location, perfect for modeling, is the currently in the tunnel, more would be needed in the future to Permafrost Tunnel between Fairbanks and Fox, Alaska. The improve upon the model. Nevertheless, the end product has Tunnel was originally made between 1963 and 1969 by the Army about 97% coverage with the remining 3% of the tunnel appearing Corps of Engineers as a bunker and storage experiment. Since as holes due to surfaces being too smooth or dark for Metashape then, the tunnel has been used extensively for permafrost, to recognize. A faster, more biology, geology, climate, mining, and engineering research. It is powerful computer would cut currently owned by the U.S. Army Cold Regions Research and down on processing time and Engineering Laboratory (CRREL). We set out to develop a useable could result in a higher VR model of the Permafrost Tunnel for educational use. We used resolution model. a 360-degree camera, Agisoft Metashape, and the Unity game engine to generate a Variable lighting, dust, and smooth Location of the useable model. Upon surfaces in the tunnel tunnel. (Modified completion, students Illustrated goggle view of the tunnel from Explore Fairbanks Photo: (Shelby Lum / Alaska Dispatch News) Aurora Tracker) from around the world and people with disabilities or illnesses Conclusion will have access to the Permafrost Tunnel. -

Changes in Peat Chemistry Associated with Permafrost Thaw Increase Greenhouse Gas Production

Changes in peat chemistry associated with permafrost thaw increase greenhouse gas production Suzanne B. Hodgkinsa,1, Malak M. Tfailya, Carmody K. McCalleyb, Tyler A. Loganc, Patrick M. Crilld, Scott R. Saleskab, Virginia I. Riche, and Jeffrey P. Chantona,1 aDepartment of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Science, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306; bDepartment of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721; cAbisko Scientific Research Station, Swedish Polar Research Secretariat, SE-981 07 Abisko, Sweden; dDepartment of Geological Sciences, Stockholm University, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden; and eDepartment of Soil, Water and Environmental Science, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721 Edited by Nigel Roulet, McGill University, Montreal, Canada, and accepted by the Editorial Board March 7, 2014 (received for review August 1, 2013) 13 Carbon release due to permafrost thaw represents a potentially during CH4 production (10–12, 16, 17), δ CCH4 also depends on 13 major positive climate change feedback. The magnitude of carbon δ CCO2,soweusethemorerobustparameterαC (10) to repre- loss and the proportion lost as methane (CH4) vs. carbon dioxide sent the isotopic separation between CH4 and CO2.Despitethe ’ (CO2) depend on factors including temperature, mobilization of two production pathways stoichiometric equivalence (17), they previously frozen carbon, hydrology, and changes in organic mat- are governed by different environmental controls (18). Dis- ter chemistry associated with environmental responses to thaw. tinguishing these controls and further mapping them is therefore While the first three of these effects are relatively well under- essential for predicting future changes in CH4 formation under stood, the effect of organic matter chemistry remains largely un- changing environmental conditions. -

Study on the Mechanical Criterion of Ice Lens Formation Based on Pore Size Distribution

applied sciences Article Study on the Mechanical Criterion of Ice Lens Formation Based on Pore Size Distribution Yuhang Liu 1,2, Dongqing Li 1 , Lei Chen 1,2 and Feng Ming 1,* 1 State Key Laboratory of Frozen Soil Engineering, Northwest Institute of Eco-Environment and Resources, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Lanzhou 730000, China; [email protected] (Y.L.); [email protected] (D.L.); [email protected] (L.C.) 2 College of Resources and Environment, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 5 November 2020; Accepted: 9 December 2020; Published: 16 December 2020 Abstract: Ice lens is the key factor which determines the frost heave in engineering construction in cold regions. At present, several theories have been proposed to describe the formation of ice lens. However, most of these theories analyzed the ice lens formation from a macroscopic view and ignored the influence of microscopic pore sizes and structures. Meanwhile, these theories lacked the support of measured data. To solve this problem, the microscopic crystallization stress was converted into the macro mean stress through the principle of statistics with the consideration of pore size distribution. The mean stress was treated as the driving force of the formation of ice lens and induced into the criterion of ice lens formation. The influence of pore structure and unfrozen water content on the mean stress was analyzed. The results indicate that the microcosmic crystallization pressure can be converted into the macro mean stress through the principle of statistics. Larger mean stress means the ice lens will be formed easier in the soil. -

Chapter 7 Seasonal Snow Cover, Ice and Permafrost

I Chapter 7 Seasonal snow cover, ice and permafrost Co-Chairmen: R.B. Street, Canada P.I. Melnikov, USSR Expert contributors: D. Riseborough (Canada); O. Anisimov (USSR); Cheng Guodong (China); V.J. Lunardini (USA); M. Gavrilova (USSR); E.A. Köster (The Netherlands); R.M. Koerner (Canada); M.F. Meier (USA); M. Smith (Canada); H. Baker (Canada); N.A. Grave (USSR); CM. Clapperton (UK); M. Brugman (Canada); S.M. Hodge (USA); L. Menchaca (Mexico); A.S. Judge (Canada); P.G. Quilty (Australia); R.Hansson (Norway); J.A. Heginbottom (Canada); H. Keys (New Zealand); D.A. Etkin (Canada); F.E. Nelson (USA); D.M. Barnett (Canada); B. Fitzharris (New Zealand); I.M. Whillans (USA); A.A. Velichko (USSR); R. Haugen (USA); F. Sayles (USA); Contents 1 Introduction 7-1 2 Environmental impacts 7-2 2.1 Seasonal snow cover 7-2 2.2 Ice sheets and glaciers 7-4 2.3 Permafrost 7-7 2.3.1 Nature, extent and stability of permafrost 7-7 2.3.2 Responses of permafrost to climatic changes 7-10 2.3.2.1 Changes in permafrost distribution 7-12 2.3.2.2 Implications of permafrost degradation 7-14 2.3.3 Gas hydrates and methane 7-15 2.4 Seasonally frozen ground 7-16 3 Socioeconomic consequences 7-16 3.1 Seasonal snow cover 7-16 3.2 Glaciers and ice sheets 7-17 3.3 Permafrost 7-18 3.4 Seasonally frozen ground 7-22 4 Future deliberations 7-22 Tables Table 7.1 Relative extent of terrestrial areas of seasonal snow cover, ice and permafrost (after Washburn, 1980a and Rott, 1983) 7-2 Table 7.2 Characteristics of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets (based on Oerlemans and van der Veen, 1984) 7-5 Table 7.3 Effect of terrestrial ice sheets on sea-level, adapted from Workshop on Glaciers, Ice Sheets and Sea Level: Effect of a COylnduced Climatic Change.