Evaluation of CRS Credited Activities During Hurricane Floyd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hurricane and Tropical Storm

State of New Jersey 2014 Hazard Mitigation Plan Section 5. Risk Assessment 5.8 Hurricane and Tropical Storm 2014 Plan Update Changes The 2014 Plan Update includes tropical storms, hurricanes and storm surge in this hazard profile. In the 2011 HMP, storm surge was included in the flood hazard. The hazard profile has been significantly enhanced to include a detailed hazard description, location, extent, previous occurrences, probability of future occurrence, severity, warning time and secondary impacts. New and updated data and figures from ONJSC are incorporated. New and updated figures from other federal and state agencies are incorporated. Potential change in climate and its impacts on the flood hazard are discussed. The vulnerability assessment now directly follows the hazard profile. An exposure analysis of the population, general building stock, State-owned and leased buildings, critical facilities and infrastructure was conducted using best available SLOSH and storm surge data. Environmental impacts is a new subsection. 5.8.1 Profile Hazard Description A tropical cyclone is a rotating, organized system of clouds and thunderstorms that originates over tropical or sub-tropical waters and has a closed low-level circulation. Tropical depressions, tropical storms, and hurricanes are all considered tropical cyclones. These storms rotate counterclockwise in the northern hemisphere around the center and are accompanied by heavy rain and strong winds (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration [NOAA] 2013a). Almost all tropical storms and hurricanes in the Atlantic basin (which includes the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea) form between June 1 and November 30 (hurricane season). August and September are peak months for hurricane development. -

NOM Technical Memorandum NWS HYDR0-21 STORM TIDE

NOM Technical Memorandum NWS HYDR0-21 STORM TIDE FREQUENCY ANALYSIS FOR THE COAST OF NORTH CAROLINA, SOUTH OF CAPE LOOKOUT Francis P. Ho Robert J. Tracey Office of Hydrology Silver Spring, Md. May 1975 UNITED STATES /NATIONAL OCEANIC AND / National Weather DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION Service Frederick B. Dent, Secretary Robert M. White. Administrator George P. Cressman, Director STORM TIDE FREQUENCY ANALYSIS FOR THE COAST OF NORTH CAROLINA, SOUTH OF CAPE LOOKOUT Contents 1. Introduction. 1 1.1 Objective and scope.......................................... 1 1.2 Authorization................................................ 1 1. 3 Study method. 2 2. Summary of historical hurricanes.................................. 2 2.1 Hurricane tracks. 2 2. 2 Historical notes. 3 3. Climatology of hurricane characteristics .......................... 12 3.1 Frequency of hurricane tracks ................................ 13 3.2 Probability distribution of hurricane intensity .............. 13 3.3 Probability distribution of radius of maximum winds .......... 14 3.4 Probability distributions of speed and direction of forward motion............................................. 14 4. Hurricane surge ....·. 14 4. 1 Surge model. • . 14 4.2 Shoaling factor.............................................. 15 5. Tide frequency analysis by joint probability method.............. 16 5.1 The joint probability method................................ 16 5. 2 Astronomical tide. 23 5.3 Tide frequencies at selected points......................... 23 5.4 Adjustment along coast...................................... 24 5. 5 Reference datum. 24 5.6 Comparison of frequency curves with observed tides and high-water marks. 26 6. Relation of this report to disaster planning..................... 27 7. Coordination and comparison with other reports................... 27 References. • . 30 ii Tables Table no. 1. Hurricane and tropical storm parameters - Cape Fear, N.C. 17 2. Hurricane and tropical storm parameters - Wrightsville Beach, N.C . -

Hurricane & Tropical Storm

5.8 HURRICANE & TROPICAL STORM SECTION 5.8 HURRICANE AND TROPICAL STORM 5.8.1 HAZARD DESCRIPTION A tropical cyclone is a rotating, organized system of clouds and thunderstorms that originates over tropical or sub-tropical waters and has a closed low-level circulation. Tropical depressions, tropical storms, and hurricanes are all considered tropical cyclones. These storms rotate counterclockwise in the northern hemisphere around the center and are accompanied by heavy rain and strong winds (NOAA, 2013). Almost all tropical storms and hurricanes in the Atlantic basin (which includes the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea) form between June 1 and November 30 (hurricane season). August and September are peak months for hurricane development. The average wind speeds for tropical storms and hurricanes are listed below: . A tropical depression has a maximum sustained wind speeds of 38 miles per hour (mph) or less . A tropical storm has maximum sustained wind speeds of 39 to 73 mph . A hurricane has maximum sustained wind speeds of 74 mph or higher. In the western North Pacific, hurricanes are called typhoons; similar storms in the Indian Ocean and South Pacific Ocean are called cyclones. A major hurricane has maximum sustained wind speeds of 111 mph or higher (NOAA, 2013). Over a two-year period, the United States coastline is struck by an average of three hurricanes, one of which is classified as a major hurricane. Hurricanes, tropical storms, and tropical depressions may pose a threat to life and property. These storms bring heavy rain, storm surge and flooding (NOAA, 2013). The cooler waters off the coast of New Jersey can serve to diminish the energy of storms that have traveled up the eastern seaboard. -

Hurricane Florence

Hurricane Florence: Building resilience for the new normal April 2019 Contents Foreword 2 An improved and consistent approach is needed to address large concentrations of Executive summary 4 harmful waste located in high hazard areas 23 Section I: The Physical Context 6 Floods contribute to marginalizing vulnerable communities in multiple ways 23 Previous events: Flooding timeline in North Carolina 8 Climate has visibly changed, sea levels have visibly risen, and these Hurricane threat – Can a Category 1 storm trends are likely to continue 23 be more dangerous than a Category 4? 9 Economic motivators can be used as Section II: Socio-Economic levers for both action and inaction 23 Disaster Landscape 10 The Saffir-Simpson Scale is not sufficient Physical Landscape 11 to charaterize potential hurricane impacts 25 Understanding the Risk Landscape 13 Even the best data has limitations and can’t substitute for caution and common sense 25 Socio-Economic Landscape 13 Recovery after Recovery 13 Section V: Recommendations 26 Environmental Risk 14 Now is the time to act – failure to do so will be far more expensive in the long run 27 Coastal Development 15 We need to critically assess where we are Section III: What Happened? 16 building and how we are incentivizing risk 27 Response 17 Shifting from siloed interventions to a holistic approach is key 27 Recovery 17 Change how we communicate risk 27 Section IV: Key Insights 20 Insurance is vital, but it needs to be the Lived experience, even repeat experience, right type of insurance and it should be doesn’t make people take action 21 a last resort 28 As a Nation, we continue to Imagine how bad it could be and plan support high-risk investments and for worse 28 unsustainable development 21 Section VI: Ways Forward 30 Hurricane Florence: Building resilience for the new normal 1 Foreword 2 Hurricane Florence: Building resilience for the new normal When people live through a catastrophic event their experience becomes a milestone moment that colors everything moving forward. -

Hurricanes of 1955 Gordon E

DECEMBEB1955 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW 315 HURRICANES OF 1955 GORDON E. DUNN, WALTER R. DAVIS, AND PAUL L. MOORE Weather Bureau Offrce, Miami, Fla. 1. GENERAL SUMMARY grouping i,n theirpaths. Thethree hurricanes entering the United States all crossed the North Carolina coast There were 13 tropical storms in 1955, (fig. 9), of which within a 6-week period and three more crossed the Mexican 10 attained hurricane force, a number known to have been coast within 150 miles of Tampico within a period of 25 exceeded only once before when 11 hurricanes were re- days. corded in 1950. This compares with a normal of about The hurricane season of 1955 was the most disastrous 9.2 tropical storms and 5 of hurricane intensity. In con- in history and for the second consecutive year broke all trast to 1954, no hurricanes crossed the coastline north of previous records for damage. Hurricane Diane was Cape Hatteras andno hurricane winds were reported north undoubtedly the greatest natural catastrophe in the his- of that point. No tropical storm of hurricane intensity tory of the United Statesand earned the unenviable affected any portion of the United States coastline along distinction of “the first billion dollar hurricane”. While the Gulf of Mexico or in Florida for the second consecutive the WeatherBureau has conservatively estimated the year. Only one hurricane has affected Florida since 1950 direct damage from Diane at between $700,000,000 and and it was of little consequence. However, similar hurri- $800,000,000, indirect losses of wages, business earnings, cane-free periods have occurred before. -

Eastern Shore Archipelago: Conservation and Scientific Assessment

Eastern Shore Archipelago: Conservation and Scientific Assessment Field Studies of a Range of Sea Islands on the Eastern Shore of Nova Scotia from Clam Harbour to Taylor Head Monday, March 5 2012 Contributors: Nick Hill, Bob Guscott, Tom Neily, Peter Green, Tom Windeyer, Chris Pepper and David Currie 1 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Purpose of the Work ........................................................................................................................ 6 1.2 NSNT Mandate ................................................................................................................................. 7 1.3 Contents of Report ........................................................................................................................... 7 2. SITE DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................................. 8 2.1 Physical Characteristics .................................................................................................................... 8 2.2 Community History ........................................................................................................................... 8 2.3 Ship Harbour National Park and Eastern Shore Seaside Park System .............................................. 9 2.4 Community Profile ........................................................................................................................... -

Examining the Effect of Visualization Tool Exposure on Local-Level Stakeholder Perceptions on Climate Change Adaptation

Examining the Effect of Visualization Tool Exposure on Local-level Stakeholder Perceptions on Climate Change Adaptation by Maliha Majeed A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Environmental Studies in Geography Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2015 © Maliha Majeed 2015 AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii ABSTRACT Vulnerabilities of human communities, driven by environmental, social, economic, and political dynamics, vary across geographical and social regions. Coastal communities are considered to be among those greatest at risk from climate impacts. To cope with these impacts, communities must assess existing vulnerabilities and adaptive capacities, and begin to adapt. Currently, community-based research often focuses on identifying vulnerabilities and possible adaptations, but rarely examines how local-level stakeholders perceive adaptation-based needs and potential action. This research study focuses on Lennox Island, in Prince Edward Island and the Town of Lockeport, in Nova Scotia to examine how two innovative visualization tools, CLIVE and AdaptNS, influence stakeholder perceptions on climate change adaptation. This study explores whether tool exposure changes perceptions of awareness and priorities for potential action among local-level decision-makers and stakeholders. It further explores which aspects of the visualization tools resonate among local-level decision-makers. This research builds on existing vulnerability assessment information established through the Partnership for Canada-Caribbean Community Climate Change Adaptation (ParCA) research project and uses a methodological approach involving semi-structured interviews and community-based workshops with local-level decision-makers and community stakeholders, respectively. -

CIMAS 2013 Annual Report

Third Annual Report NOAA Cooperative Agreement NA10OAR4320143 July 1, 2012 – June 30, 2013 Peter B. Ortner, Director David Die, Associate Director UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI ROSENSTIEL SCHOOL OF MARINE AND ATMOSPHERIC SCIENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………. 2 II. CIMAS Mission and Organization…………………………………………………….…. 6 III. Personnel………………………………………………………………………………..... 9 IV. Funding………………………………………………………………………………….. 12 V. Research Themes Overview…………………………………………………………….. 17 VI. Research Reports Theme 1: Climate Research Impacts………………………………………………… 20 Theme 2: Tropical Weather…………………………………………………………. 51 Theme 3: Sustained Ocean and Coastal Observations……………………………… 100 Theme 4: Ocean Modeling…………………………………………….……………. 153 Theme 5: Ecosystem Modeling and Forecasting…………………………………… 168 Theme 6: Ecosystem Management…….…………………………………………… 182 Theme 7: Protection and Restoration of Resources………………………………… 200 VII. Education and Outreach………………………………………………………………… 238 VIII. CIMAS Fellows and Executive Advisory Board………………………………………. 250 IX. Awards and Honors……………………………………………………………………... 254 X. Postdoctoral Fellows and Graduate Students…………………………………………… 256 XI. Research Staff…………………………………………………………………………… 257 XII. Visiting Scientist Program……………………………………………………………… 260 XIII Publications ……………………………………………………………………………. 261 1 I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies (CIMAS) is a research institute hosted at the University of Miami (UM) in the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science -

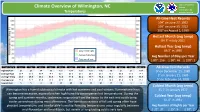

Climate Overview of Wilmington, NC

National Weather Climate Overview of Wilmington, NC Service Wilmington, NC Temperatures weather.gov/ilm All-time Heat Records 104° on June 27, 1952 103° on June 30, 2012 103° on August 1, 1999 Hottest Month (avg temp) 84.7° in July 2012 Hottest Year (avg temp) Daily record highs 66.5° in 1990 Average highs/lows Avg Number of Days per Year Daily record lows ≥ 80°: 156 ≥ 90°: 46 ≥ 100°: 1 National Weather Service Weather National TEMP DATA Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec ANNUAL All-time Cold Records Highest Ever 82 85 94 95 101 104 103 103 100 98 87 82 104 0° on December 25, 1989 Average High 56.4 59.9 66.4 74.2 80.7 86.9 89.7 88.1 83.7 75.7 68.0 59.3 74.1 Average Temp 46.0 48.9 55.1 62.9 70.4 77.8 81.1 79.7 74.6 65.2 56.7 48.6 63.9 5° on January 21, 1985 Average Low 35.6 37.9 43.8 51.6 60.0 68.7 72.6 71.3 65.6 54.6 45.4 37.8 53.7 5° on February 14, 1899 Lowest Ever 5 5 9 28 35 48 54 55 42 27 16 0 0 Coldest Month (avg temp) Wilmington has a humid subtropical climate with hot summers and cool winters. Summertime heat 35.7° in January 1977 can become excessive, especially when high humidity accompanies hot temperatures. During the Coldest Year (avg temp) spring and summer months, seabreezes originating from the ocean to the east and south bring 61.0° in 1981 cooler air onshore during most afternoons. -

Figure 1. Tracks of Land Falling Major Hurricanes in the Period 1951-1960 from NWS Technical 3

5B.6 RE-ANALYSIS OF HURRICANES CONNIE AUGUST 12, 1955 AND IONE SEPTEMBER 19, 1955 Hugh D. Cobb, III NOAA/NWS/Tropical Prediction Center 1. INTRODUCTION Even though the HURDAT database indicates that Connie was considered a Category Three hurricane The 1950s were a particularly active decade for for North Carolina, the six-hourly data in HURDAT hurricane landfalls along the east coast of the United indicates Hurricane Connie was a Category One States. The years 1954 and 1955 were especially active hurricane at 1200 UTC 12 August, several hours before with six hurricanes making landfall in the area from the time of landfall in North Carolina. HURDAT also North Carolina to New England with five of the indicates Hurricane Ione was a Category Two hurricane hurricanes considered major (Category 3 or higher) at 0600 UTC 19 September, five hours before landfall in landfalls (Figure 1). Hurricanes Connie and Ione were North Carolina. Thus a discrepancy exists within the the two storms in the 1955 season that were considered HURDAT database. NOAA Technical Memoranda NWS major landfalls. This active period of hurricane activity TPC-4 also indicates Hurricanes Connie and Ione were provided the motivation to create the National Hurricane Category Three hurricanes in North Carolina. Research Project, which evolved into the Hurricane Research Division. The re-analysis of both Hurricanes Connie and Ione supports the findings in the six hourly data in the The National Hurricane Center's (NHC's) North HURDAT database. Atlantic hurricane database (HURDAT) of six-hourly positions and intensities was created in the 1960s in 2. -

Wrightsville Beach

DRAFT TOWN OF WRIGHTSVILLE BEACH HAZARD MITIGATION PLAN November 20, 2009 Prepared By: Wilmington, North Carolina DRAFT Wrightsville Beach Hazard Mitigation Plan Table of Contents PAGE Section 1. Introduction A. INTRODUCTION ............................................. 1-1 B. STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM . 1-1 C. HAZARD MITIGATION LEGISLATION . 1-2 D. TOWN OF WRIGHTSVILLE BEACH HAZARD MITIGATION PLAN . 1-3 E. PLAN ORGANIZATION ......................................... 1-4 F. PLANNING PROCESS ......................................... 1-5 Section 2. Community Profile A. LOCATION AND GENERAL TOPOGRAPHY . 2-1 B. HISTORY .................................................. 2-1 C. CLIMATE .................................................. 2-3 D. DEMOGRAPHIC SUMMARY ..................................... 2-4 1. Permanent Population . 2-4 2. Seasonal Population ..................................... 2-5 3. Population Profile - Age .................................. 2-5 4. Housing ............................................. 2-6 5. Economy ............................................. 2-7 Section 3. Hazard Identification A. INTRODUCTION ............................................. 3-1 B. HURRICANES ............................................... 3-2 1. Description ........................................... 3-2 2. Historical Impact ....................................... 3-4 a. October 5 to 18, 1954 (Hurricane Hazel) . 3-4 b. August 3 to 14, 1955 (Hurricane Connie) . 3-5 c. August 7 to 21, 1955 (Hurricane Diane) . 3-5 d. September 10 to 23, 1955 (Hurricane Ione) . 3-6 e. August 29 to September 13, 1960 (Hurricane Donna) . 3-6 f. September 9 to 14, 1984 (Hurricane Diana) . 3-7 g. July 5 to 12, 1996 (Hurricane Bertha) . 3-7 h. August 23 to September 5, 1996 (Hurricane Fran) . 3-8 i. August 19 to 30, 1998 (Hurricane Bonnie) . 3-8 j. August 24 to September 7, 1999 (Hurricane/Tropical Storm Dennis) 3-9 k. September 7 to 18, 1999 (Hurricane Floyd) . 3-10 November 20, 2009 Page C-1 Table of Contents DRAFT Wrightsville Beach Hazard Mitigation Plan 3. -

Virginia HURRICANES by Barbara Mcnaught Watson

Virginia HURRICANES By Barbara McNaught Watson A hurricane is a large tropical complex of thunderstorms forming spiral bands around an intense low pressure center (the eye). Sustained winds must be at least 75 mph, but may reach over 200 mph in the strongest of these storms. The strong winds drive the ocean's surface, building waves 40 feet high on the open water. As the storm moves into shallower waters, the waves lessen, but water levels rise, bulging up on the storm's front right quadrant in what is called the "storm surge." This is the deadliest part of a hurricane. The storm surge and wind driven waves can devastate a coastline and bring ocean water miles inland. Inland, the hurricane's band of thunderstorms produce torrential rains and sometimes tornadoes. A foot or more of rain may fall in less than a day causing flash floods and mudslides. The rain eventually drains into the large rivers which may still be flooding for days after the storm has passed. The storm's driving winds can topple trees, utility poles, and damage buildings. Communication and electricity is lost for days and roads are impassable due to fallen trees and debris. A tropical storm has winds of 39 to 74 mph. It may or may not develop into a hurricane, or may be a hurricane in its dissipating stage. While a tropical storm does not produce a high storm surge, its thunderstorms can still pack a dangerous and deadly punch. Agnes was only a tropical storm when it dropped torrential rains that lead to devastating floods in Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia.