History, Power and Monstrosity from Shakespeare to the Fin De Siecle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 30 Easter Vacation 2005

The Oxford University Doctor Who Society Magazine TThhee TTiiddeess ooff TTiimmee I ssue 30 Easter Vacation 2005 The Tides of Time 30 · 1 · Easter Vacation 2005 SHORELINES TThhee TTiiddeess ooff TTiimmee By the Editor Issue 30 Easter Vacation 2005 Editor Matthew Kilburn The Road to Hell [email protected] I’ve been assuring people that this magazine was on its way for months now. My most-repeated claim has probably Bnmsdmsr been that this magazine would have been in your hands in Michaelmas, had my hard Wanderers 3 drive not failed in August. This is probably true. I had several days blocked out in The prologue and first part of Alex M. Cameron’s new August and September in which I eighth Doctor story expected to complete the magazine. However, thanks to the mysteries of the I’m a Doctor Who Celebrity, Get Me Out of guarantee process, I was unable to Here! 9 replace my computer until October, by James Davies and M. Khan exclusively preview the latest which time I had unexpectedly returned batch of reality shows to full-time work and was in the thick of the launch activities for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Another The Road Not Taken 11 hindrance was the endless rewriting of Daniel Saunders on the potentials in season 26 my paper for the forthcoming Doctor Who critical reader, developed from a paper I A Child of the Gods 17 gave at the conference Time And Relative Alex M. Cameron’s eighth Doctor remembers an episode Dissertations In Space at Manchester on 1 from his Lungbarrow childhood July last year. -

Dr Who Pdf.Pdf

DOCTOR WHO - it's a question and a statement... Compiled by James Deacon [2013] http://aetw.org/omega.html DOCTOR WHO - it's a Question, and a Statement ... Every now and then, I read comments from Whovians about how the programme is called: "Doctor Who" - and how you shouldn't write the title as: "Dr. Who". Also, how the central character is called: "The Doctor", and should not be referred to as: "Doctor Who" (or "Dr. Who" for that matter) But of course, the Truth never quite that simple As the Evidence below will show... * * * * * * * http://aetw.org/omega.html THE PROGRAMME Yes, the programme is titled: "Doctor Who", but from the very beginning – in fact from before the beginning, the title has also been written as: “DR WHO”. From the BBC Archive Original 'treatment' (Proposal notes) for the 1963 series: Source: http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/doctorwho/6403.shtml?page=1 http://aetw.org/omega.html And as to the central character ... Just as with the programme itself - from before the beginning, the central character has also been referred to as: "DR. WHO". [From the same original proposal document:] http://aetw.org/omega.html In the BBC's own 'Radio Times' TV guide (issue dated 14 November 1963), both the programme and the central character are called: "Dr. Who" On page 7 of the BBC 'Radio Times' TV guide (issue dated 21 November 1963) there is a short feature on the new programme: Again, the programme is titled: "DR. WHO" "In this series of adventures in space and time the title-role [i.e. -

List of All the Audiobooks That Are Multiuse (Pdf 608Kb)

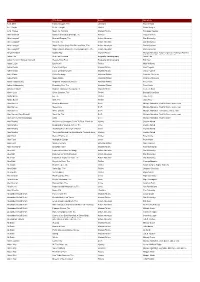

Authors Title Name Genre Narrators A. D. Miller Faithful Couple, The Literature Patrick Tolan A. L. Gaylin If I Die Tonight Thriller Sarah Borges A. M. Homes Music for Torching Modern Fiction Penelope Rawlins Abbi Waxman Garden of Small Beginnings, The Humour Imogen Comrie Abie Longstaff Emerald Dragon, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Firebird, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Blizzard Bear, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Young Apprentice, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abigail Tarttelin Golden Boy Modern Fiction Multiple Narrators, Toby Longworth, Penelope Rawlins, Antonia Beamish, Oliver J. Hembrough Adam Hills Best Foot Forward Biography Autobiography Adam Hills Adam Horovitz, Michael Diamond Beastie Boys Book Biography Autobiography Full Cast Adam LeBor District VIII Thriller Malk Williams Adèle Geras Cover Your Eyes Modern Fiction Alex Tregear Adèle Geras Love, Or Nearest Offer Modern Fiction Jenny Funnell Adele Parks If You Go Away Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adele Parks Spare Brides Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adrian Goldsworthy Brigantia: Vindolanda, Book 3 Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adrian Goldsworthy Encircling Sea, The Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adriana Trigiani Supreme Macaroni Company, The Modern Fiction Laurel Lefkow Aileen Izett Silent Stranger, The Thriller Bethan Dixon-Bate Alafair Burke Ex, The Thriller Jane Perry Alafair Burke Wife, The Thriller Jane Perry Alan Barnes Death in Blackpool Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes Nevermore Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes White Ghosts Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Tom Baker, and a. cast Alan Barnes, Gary Russell Next Life, The Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. -

Others 60 Seconds to Save the World 34.99 Abyss Conspiracy Green Version 26.99 Adrenaline 89.99 Affliction Salem 1692 39.99 Afte

OTHERS 60 SECONDS TO SAVE THE WORLD 34.99 ABYSS CONSPIRACY GREEN VERSION 26.99 ADRENALINE 89.99 AFFLICTION SALEM 1692 39.99 AFTER THE VIRUS 34.99 AIRSHIP CITY 49.99 ALICE IN WORDLAND 39.99 ALIEN WARS 27.99 ALTIPLANO THE TRAVELER EXPANSION 39.99 ALUBARI 84.99 AMERIGO 74.99 AMONG THE STARS 55.99 AMONG THE STARS MINIATURES PACK 39.99 AMONG THE STARS REVIVAL EXPANSION 69.99 AMONG THE STARS THE AMBASSADORS EXPANSION 39.99 ANACHRONY 89.99 ANCESTREE 39.99 ANKHOR 34.99 ASCENSION CHRONICLE OF A GODSLAYER 49.99 ASCENSION DARKNESS UNLEASHED 33.99 ASCENSION GIFT OF THE ELEMENTS 52.99 ASCENSION THEME PACK RAT QUEEN 5.75 ATLANDICE 54.99 BATMAN ANIMATED SERIES GOTHAM UNDER SIEGE MASTERMINDS MAYHEM 19.99 BATTLE FOR GREYPORT PIRATES EXPANSION 29.99 BEARS VS BABIES 44.99 BEARS VS BABIES NSFW EXPANSION 17.99 BEFORE THERE WERE STARS 54.99 BETWEEN TWO CITIES CAPITALS EXPANSION 26.99 BLACKOUT HONG KONG 89.99 BLOODBORNE HUNTERS NIGHTMARE EXPANSION 19.99 BLOSSOMS 34.99 BOARDGAMEGEEK CARD GAME 26.99 BOTTLE IMP (NEW EDITION) 24.99 BRAINTOPIA 23.99 BREAK THE CODE 22.99 BROADHORNS 79.99 BUFFY VAMPIRE SLAYER BOARDGAME FRIENDS FRENEMIES EXP 39.99 BULLFROGS 34.99 BUNNY KINGDOM IN THE SKY EXPANSION 47.99 GAME OF THRONES LCG 2ND EDITION 57.99 CALL TO ADVENTURE NAME OF THE WIND EXPANSION 24.99 CAMELOT THE BUILD 25 CANDY CHASER 21.99 CAPTAIN CARCASS 33.99 CARDLINE ANIMALS 21.99 CARNIVAL OF MONSTERS 49.99 CATCH ME 37.99 CHECKPOINT CHARLIE 36.99 CHICKWOOD FOREST 32.99 CHIMERA 19.99 CHROMINO 34.99 CLACKS A DISCWORLD BOARD GAME 69.99 CLAUSTROPHOBIA: DE PROFUNDIS EXPANSION 49.99 -

Issue 53 • July 2013

ISSUE 53 • JULY 2013 VORTEX MAGAZINE | PAGE 2 Welcome to Big Finish! We love stories and we make great full-cast audio drama and audiobooks you can buy on CD and/or download Our audio productions are based on much-loved TV series like Doctor Who, Dark Shadows, Blake’s 7, Stargate and Highlander as well as classic characters such as Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the Opera and Dorian Gray, plus original creations such as Graceless and The Adventures of Bernice Summerfield. We publish a growing number of books (non-fiction, novels and short stories) from new and established authors. You can access a video guide to the site by clicking here. Subscribers get more at bigfinish.com! If you subscribe, depending on the range you subscribe to, you get free audiobooks, PDFs of scripts, extra behind-the-scenes material, a bonus release and discounts. www.bigfinish.com @bigfinish /thebigfinish VORTEX MAGAZINE | PAGE 3 VORTEX MAGAZINE | PAGE 4 EDITORIAL Sometimes, I wonder if there’s too much Doctor Who in my ISSUE 53 • JULY 2013 life. My walk to the train station in the morning is twenty-five minutes, give or take. It’s annoying that I have to traipse all the way down to West Croydon (trains to the station nearest the BF office only run at certain, less convenient, times from the nearer SNEAK PREVIEWS East Croydon), but that walk is about the length of a Doctor Who AND WHISPERS episode, so before I even arrive at work, I’m in a Who-ey frame of mind. -

Eco-Activism in Doctor Who During the 1970S

Author: Jørgensen, Dolly. Title: A Blueprint for Destruction: Eco-Activism in Doctor Who during the 1970s A Blueprint for Destruction: Eco-Activism in Doctor Who during the 1970s Dolly Jørgensen Umeå University In 1972, the editors of a two-year old environmentalist magazine named The Ecologist published a special issue titled A Blueprint for Survival, which subsequently sold over 750,000 copies as a book. This manifesto of the early eco-activist movement lamented the unsustainable industrial way of life that had developed after WWII and proposed a new 'stable society' with minimal ecological destruction, conservation of materials and energy, zero population growth, and a social system that supported individual fulfillment under the first three conditions (Goldsmith et al. 30). Blueprint received tremendous attention in the British press and became a seminal text for the British Green movement (Veldman 227–236). This environmental movement of the 1960s and 1970s was substantially different from traditional environmentalists of the early twentieth century who tended to be conservationists interested in wildlife and landscapes. The new environmentalists, whom Meredith Veldman labels eco-activists, "condemned not only environmental degradation but also the society that did the degrading" (210). They combined critiques against pollution with calls for limited population growth and refinement of social systems. Although the early eco-activist movement in Britain petered out politically in the late 1970s (it arose again in the mid-1980s), its radical environmental ideas had begun to permeate society. Vol 3 , At the same time that eco-activists were establishing their agenda, the BBC serial No television drama Doctor Who was enjoying its successful establishment in British 2 popular culture. -

Doctor Who 1 Doctor Who

Doctor Who 1 Doctor Who This article is about the television series. For other uses, see Doctor Who (disambiguation). Doctor Who Genre Science fiction drama Created by • Sydney Newman • C. E. Webber • Donald Wilson Written by Various Directed by Various Starring Various Doctors (as of 2014, Peter Capaldi) Various companions (as of 2014, Jenna Coleman) Theme music composer • Ron Grainer • Delia Derbyshire Opening theme Doctor Who theme music Composer(s) Various composers (as of 2005, Murray Gold) Country of origin United Kingdom No. of seasons 26 (1963–89) plus one TV film (1996) No. of series 7 (2005–present) No. of episodes 800 (97 missing) (List of episodes) Production Executive producer(s) Various (as of 2014, Steven Moffat and Brian Minchin) Camera setup Single/multiple-camera hybrid Running time Regular episodes: • 25 minutes (1963–84, 1986–89) • 45 minutes (1985, 2005–present) Specials: Various: 50–75 minutes Broadcast Original channel BBC One (1963–1989, 1996, 2005–present) BBC One HD (2010–present) BBC HD (2007–10) Picture format • 405-line Black-and-white (1963–67) • 625-line Black-and-white (1968–69) • 625-line PAL (1970–89) • 525-line NTSC (1996) • 576i 16:9 DTV (2005–08) • 1080i HDTV (2009–present) Doctor Who 2 Audio format Monaural (1963–87) Stereo (1988–89; 1996; 2005–08) 5.1 Surround Sound (2009–present) Original run Classic series: 23 November 1963 – 6 December 1989 Television film: 12 May 1996 Revived series: 26 March 2005 – present Chronology Related shows • K-9 and Company (1981) • Torchwood (2006–11) • The Sarah Jane Adventures (2007–11) • K-9 (2009–10) • Doctor Who Confidential (2005–11) • Totally Doctor Who (2006–07) External links [1] Doctor Who at the BBC Doctor Who is a British science-fiction television programme produced by the BBC. -

A Comparative Corpus Analysis

T.C. NECMETTIN ERBAKAN UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN LANGUAGES TEACHING DIVISION OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING SPOKEN LANGUAGE IN TV SERIES: A COMPARATIVE CORPUS ANALYSIS Hatice SEZGİN M. A. THESIS Supervisor Assist. ProF. Dr. MustaFa Serkan ÖZTÜRK Konya, 2019 T.C. NECMETTIN ERBAKAN UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN LANGUAGES TEACHING DIVISION OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING SPOKEN LANGUAGE IN TV SERIES: A COMPARATIVE CORPUS ANALYSIS Hatice SEZGİN M. A. THESIS Supervisor Assist. ProF. Dr. MustaFa Serkan ÖZTÜRK Konya, 2019 i T.C NECMETTİN ERBAKAN UNİVERSITESI Eğitim Bilimleri Enstitüsü Müdürlüğü KONYA BİLİMSEL ETİK SAYFASI Adı Soyadı Hatice SEZGİN Numarası 108304031007 Ana Bilinl / Bilim Dalı abancı Diller Eğitimi / İngiliz Dili Eğitimi Tezli Yüksek Lisans x Programı Doktora Spokcn Language in TV Series: A Comparativc Corpus Analysis ezin Adı Bu tezin hazırlanmasında bilimsel etiğe ve akademik kurallara özcnle riayet edildiğini, tez içindeki bütün bilgilerin etik davranış ve akademik kurallar çerçevesindc elde edilerek sunulduğunu, aynca tez yazım kurallarına uygun olarak hazırlanan bu çalışmada başkalarının eserlerinden yararlanılması durumunda bilimsel kurallara uygun olarak atıf yapıldığını bildiririm. 31/05/2019 Hatice T.C. NECMETTİN ERBAKANÜNİVERSİTESİ Eğitim Bilimleri Enstitüsü Müdürlüğü KONYA EĞİTİM BİLİMLERİ ÇNST'JUSÜ YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ KABUL FORMU Adı Soyadı Hatice SEZGİN Numarası 108304031007 Ana Bilim Dalı Yabancı Diller Eğitimi Bilim Dalı İngiliz Dili Eğitimi Programı Tezli Yüksek Lisans Tez Danışmanı Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Mustafa Serkan Öztürk Spokcn Language in TV Series: A Comparative Corpus Analysis Tezin Adı Yukarıda adı geçen öğrenci tarafından hazırlanan Spokcn Language in TV Series: A Comparative Corpus Analysis başlıklı bu çalışma 31 /05/2019 tarihinde yapılan savunma sınavı sonucunda oybirliği/oyçokluğu ile başarılı bulunarak, jürımiz tarafından yüksek lisans tezi olarak kabul edilmiştir. -

July Customer Order Form

OrdErS PREVIEWS world.com duE th 18 JUL 2013 JULY COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 6/6/2013 10:07:33 AM Customizable Name tag!t Available only ARMY OF DARKNESS: from your local “S-MART WORK SHIRT” T-SHIRT comic shop! Preorder now! DOCTOR WHO: THE WALKING DEAD: “IT SEEMS TO ME” DEADPOOL: FLOOR POOL “I GOT THIS” T-SHIRT HEATHER T-SHIRT PX WHITE T-SHIRT Preorder now! Preorder now! Preorder now 7 July 13 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 6/6/2013 9:46:06 AM The STar WarS #1 (of 8) SeX CrimiNaLS #1 Dark horSe ComiCS image ComiCS faireST iN aLL The LaND hC DC ComiCS / VerTigo kiSS me, SaTaN #1 (of 5) raT QueeNS #1 Dark horSe ComiCS image ComiCS PoWerPuff girLS #1 (of 5) iDW PubLiShiNg foreVer eViL #1 Thor: goD of ThuNDer DC ComiCS #13 marVeL ComiCS Jul13 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 6/6/2013 2:52:27 PM Featured Items COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS COW BOY VOLUME 2: UNCONQUERABLE GN l ARCHAIA ENTERTAINMENT LLC AFTERLIFE WITH ARCHIE #1 l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS GOD IS DEAD #1 l AVATAR PRESS INC THE SIMPSONS’ TREEHOUSE OF HORROR #19 l BONGO COMICS 1 SONS OF ANARCHY #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS RASL COMPLETE HC l CARTOON BOOKS KINGS WATCH #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 CODENAME: ACTION #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT THE ART OF SEAN PHILLIPS HC l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT CO-MIX RETROSPECTIVE SPIEGELMAN HC l DRAWN & QUARTERLY BOXERS GN l :01 FIRST SECOND SAINTS GN l :01 FIRST SECOND SAILOR MOON: SHORT STORIES VOLUME 1 GN l KODANSHA COMICS WORLD OF WARCRAFT TRIBUTE SC l UDON ENTERTAINMENT -

Doctor Who Assistants

COMPANIONS FIFTY YEARS OF DOCTOR WHO ASSISTANTS An unofficial non-fiction reference book based on the BBC television programme Doctor Who Andy Frankham-Allen CANDY JAR BOOKS . CARDIFF A Chaloner & Russell Company 2013 The right of Andy Frankham-Allen to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Copyright © Andy Frankham-Allen 2013 Additional material: Richard Kelly Editor: Shaun Russell Assistant Editors: Hayley Cox & Justin Chaloner Doctor Who is © British Broadcasting Corporation, 1963, 2013. Published by Candy Jar Books 113-116 Bute Street, Cardiff Bay, CF10 5EQ www.candyjarbooks.co.uk A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. Dedicated to the memory of... Jacqueline Hill Adrienne Hill Michael Craze Caroline John Elisabeth Sladen Mary Tamm and Nicholas Courtney Companions forever gone, but always remembered. ‘I only take the best.’ The Doctor (The Long Game) Foreword hen I was very young I fell in love with Doctor Who – it Wwas a series that ‘spoke’ to me unlike anything else I had ever seen. -

Dead Ringers Was Hastily Composed to Fill in the Gap And, Fortunately, Enough Time Remained Following the Filming Ofthe Shattered Clocks and Yesterday’S Avatar

SUNDAY TV 19 October SERIAL 9J The new co-producers of Doctor Who must have felt themselves baptised by fire, for on their first day on the job, the story that should have filled the third position of the season,Andromeda Sunset, collapsed, and a replacement was needed. Dead Ringers was hastily composed to fill in the gap and, fortunately, enough time remained following the filming ofThe Shattered Clocks and Yesterday’s Avatar. The writing team of Edward Chan and Brad Connors were commissioned for this story, but the names were obvious pseudonyms. Some speculated that Josh Whedon and David Greenbelt had “pulled a City of Death”. The cast and crew flew to Minneapolis for four weeks in June to produce this eight-part (traditional measurement) tale. Upon the debut, controversy erupted, with some complaining about the heightened level of violence, combined with the humorous approach of the story. Some felt the effect wasn’t something the show should emulate. Part one debuted on Sunday, October 19 with 9.7 million view- ers, good for 28th place. Dead Ringers was partially rewritten, with scenes taken from the aborted BBC Books submission The Dead of Winter. VERA STRONG With friends like these… Ryan finds himself in double trouble Doctor Who, BBC1 7.30pm 7.00pm Mighty Mor- LETTERS phin Flower Arrangers The Shattered Clocks was an In The Grass is Always Greener unsatisfying conclusion to the The Arrangers find themselves trilogy begun in Twilight’s Last at the mercy of giant radioactive Gleaming. It feels like nothing more than a lot of running around, crabgrass. -

Towards Left Duff S Mdbg Holt Winters Gai Incl Tax Drupal Fapi Icici

jimportneoneo_clienterrorentitynotfoundrelatedtonoeneo_j_sdn neo_j_traversalcyperneo_jclientpy_neo_neo_jneo_jphpgraphesrelsjshelltraverserwritebatchtransactioneventhandlerbatchinsertereverymangraphenedbgraphdatabaseserviceneo_j_communityjconfigurationjserverstartnodenotintransactionexceptionrest_graphdbneographytransactionfailureexceptionrelationshipentityneo_j_ogmsdnwrappingneoserverbootstrappergraphrepositoryneo_j_graphdbnodeentityembeddedgraphdatabaseneo_jtemplate neo_j_spatialcypher_neo_jneo_j_cyphercypher_querynoe_jcypherneo_jrestclientpy_neoallshortestpathscypher_querieslinkuriousneoclipseexecutionresultbatch_importerwebadmingraphdatabasetimetreegraphawarerelatedtoviacypherqueryrecorelationshiptypespringrestgraphdatabaseflockdbneomodelneo_j_rbshortpathpersistable withindistancegraphdbneo_jneo_j_webadminmiddle_ground_betweenanormcypher materialised handaling hinted finds_nothingbulbsbulbflowrexprorexster cayleygremlintitandborient_dbaurelius tinkerpoptitan_cassandratitan_graph_dbtitan_graphorientdbtitan rexter enough_ram arangotinkerpop_gremlinpyorientlinkset arangodb_graphfoxxodocumentarangodborientjssails_orientdborientgraphexectedbaasbox spark_javarddrddsunpersist asigned aql fetchplanoriento bsonobjectpyspark_rddrddmatrixfactorizationmodelresultiterablemlibpushdownlineage transforamtionspark_rddpairrddreducebykeymappartitionstakeorderedrowmatrixpair_rddblockmanagerlinearregressionwithsgddstreamsencouter fieldtypes spark_dataframejavarddgroupbykeyorg_apache_spark_rddlabeledpointdatabricksaggregatebykeyjavasparkcontextsaveastextfilejavapairdstreamcombinebykeysparkcontext_textfilejavadstreammappartitionswithindexupdatestatebykeyreducebykeyandwindowrepartitioning