Issue 30 Easter Vacation 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tom Baker Is Back As the Doctor for the Romance of Crime and the English Way of Death

WWW.BIGFINISH.COM • NEW AUDIO ADVENTURES GO FOURTH! TOM BAKER IS BACK AS THE DOCTOR FOR THE ROMANCE OF CRIME AND THE ENGLISH WAY OF DEATH ISSUE 71 • JANUARY 2015 WELCOME TO BIG FINISH! We love stories and we make great full-cast audio dramas and audiobooks you can buy on CD and/or download Big Finish… Subscribers get more We love stories. at bigfinish.com! Our audio productions are based on much- If you subscribe, depending on the range you loved TV series like Doctor Who, Dark subscribe to, you get free audiobooks, PDFs Shadows, Blake’s 7, The Avengers and of scripts, extra behind-the-scenes material, a Survivors as well as classic characters such as bonus release, downloadable audio readings of Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the Opera new short stories and discounts. and Dorian Gray, plus original creations such as Graceless and The Adventures of Bernice www.bigfinish.com Summerfield. You can access a video guide to the site at We publish a growing number of books (non- www.bigfinish.com/news/v/website-guide-1 fiction, novels and short stories) from new and established authors. WWW.BIGFINISH.COM @BIGFINISH /THEBIGFINISH VORTEX MAGAZINE PAGE 3 Sneak Previews & Whispers Editorial HEN PLANNING ahead for this month’s issue of W Vortex, David Richardson suggested that I might speak to Tom Baker, to preview his new season of adventures, and the Gareth Roberts novel adaptations. That was one of those moments when excitement and fear hit me in equal measure. I mean, this is Tom Baker! TOM BAKER! I was born 11 days after he made his first appearance in Planet of the Spiders, so growing up, he was my Doctor. -

Uncle Hugo's Science Fiction Bookstore Uncle Edgar's Mystery Bookstore 2864 Chicago Ave

Uncle Hugo's Science Fiction Bookstore Uncle Edgar's Mystery Bookstore 2864 Chicago Ave. S., Minneapolis, MN 55407 Newsletter #103 September — November, 2013 Hours: M-F 10 am to 8 pm RECENTLY RECEIVED AND FORTHCOMING SCIENCE FICTION Sat. 10 am to 6 pm; Sun. Noon to 5 pm ALREADY RECEIVED Uncle Hugo's 612-824-6347 Uncle Edgar's 612-824-9984 Doctor Who Magazine #460 (DWM heads to Trenzalore to find out the name of Fax 612-827-6394 the Doctor; tribute to the man who designed the Daleks; more).. $9.99 E-mail: [email protected] Doctor Who Magazine #461 (Doctor Who & the Daleks: what playing the Doctor Website: www.UncleHugo.com meant to Peter Cushing; more)......................................... $9.99 Doctor Who Magazine #462 (Regeneration: Who will be the twelfth Doctor? How’s Business? more)............................................................ $9.99 Fantasy & Science Fiction July / August 2013 (New fiction, reviews, more) By Don Blyly ................................................................. $7.99 Fantasy & Science Fiction May / June 2013 (New fiction, reviews, more) As many of our older customers ................................................................. $7.99 retire, they often move from a large old Locus #629 June 2013 (Interviews with Rudy Rucker and Sofia Samatar; Nebula house with lots of space to store books to winners; awards info; forthcoming books; industry news, reviews, more). $7.50 a smaller place with a lot less room for Locus #630 July 2013 (Interviews with Maria Dahvana Headley and Neil Gaiman; in books, resulting in many bags or boxes of books being brought to the Uncles. memoriam: Jack Vance and Iain Banks; Locus Award winners; industry news, reviews, more) This has been going on for many years, ................................................................ -

From Real Time to Reel Time: the Films of John Schlesinger

From Real Time to Reel Time: The Films of John Schlesinger A study of the change from objective realism to subjective reality in British cinema in the 1960s By Desmond Michael Fleming Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2011 School of Culture and Communication Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne Produced on Archival Quality Paper Declaration This is to certify that: (i) the thesis comprises only my original work towards the PhD, (ii) due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all other material used, (iii) the thesis is fewer than 100,000 words in length, exclusive of tables, maps, bibliographies and appendices. Abstract The 1960s was a period of change for the British cinema, as it was for so much else. The six feature films directed by John Schlesinger in that decade stand as an exemplar of what those changes were. They also demonstrate a fundamental change in the narrative form used by mainstream cinema. Through a close analysis of these films, A Kind of Loving, Billy Liar, Darling, Far From the Madding Crowd, Midnight Cowboy and Sunday Bloody Sunday, this thesis examines the changes as they took hold in mainstream cinema. In effect, the thesis establishes that the principal mode of narrative moved from one based on objective realism in the tradition of the documentary movement to one which took a subjective mode of narrative wherein the image on the screen, and the sounds attached, were not necessarily a record of the external world. The world of memory, the subjective world of the mind, became an integral part of the narrative. -

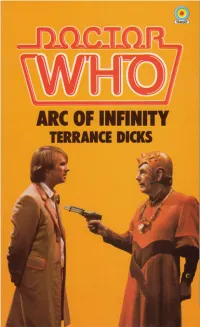

Doctor Returns to Gallifrey, He Learns That His Bio Data Extract Has Been Stolen from the Time Lords’ Master Computer Known As the Matrix

When the Doctor returns to Gallifrey, he learns that his bio data extract has been stolen from the Time Lords’ master computer known as the Matrix. The bio data extract is a detailed description of the Doctor’s molecular structure—and this information, in the wrong hands, could be exploited with disastrous effect. The Gallifreyan High Council believe that anti-matter will be infiltrated into the universe as a result of the theft. In order to render the information useless, they decide the Doctor must die... Among the many Doctor Who books available are the following recently published titles: Doctor Who and the Sunmakers Doctor Who Crossword Book Doctor Who — Time-Flight Doctor Who — Meglos Doctor Who — Four to Doomsday Doctor Who — Earthshock GB £ NET +001.35 ISBN 0-426-19342-3 UK: £1.35 *Australia: $3.95 *Recommended Price ,-7IA4C6-bjdecf-:k;k;L;N;p TV tie-in DOCTOR WHO ARC OF INFINITY Based on the BBC television serial by Johnny Byrne by arrangement with the British Broadcasting Corporation TERRANCE DICKS A TARGET BOOK published by The Paperback Division of W. H. Allen & Co. Ltd A Target Book Published in 1983 by the Paperback Division of W.H. Allen & Co. Ltd A Howard & WyndhamCompany 44 Hill Street, London W1X 8LB First published in Great Britain by W.H. Allen & Co. Ltd 1983 Novelisation copyright © Terrance Dicks 1983 Original script copyright © Johnny Byrne 1982 ‘Doctor Who’ series copyright © British Broadcasting Corporation 1982, 1983 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Anchor Brendon Ltd, Tiptree, Essex ISBN 0 426 19342 3 This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

Sociology 2013

LEFT HEADER RIGHT HEADER SOCIOLOGY 2013 SCHOLARLY RESOURCES PB DistributorClick of I.B.Tauris on the regional • Manchester link to view University more product Press information • Pluto Press or to •buy. Zed Books 1 LEFT HEADER RIGHT HEADER Social & Cultural Studies Collections Palgrave Connect presents libraries with a flexible approach to building an ebook Collection with over 11,000 titles offered in the Humanities, the Social Sciences and Business. Our ebooks are published simultaneously with the print edition and uploaded into the current collections. Over 530 ebooks publications are available on Palgrave Connect available Our Social Sciences Collections include our Sociology, Social Policy, Criminology & Criminal Justice, Psychology, in this area ‘ Gender Studies and Anthropology scholarly titles. Our prestigious and innovative programme features established authors and rising stars from across the globe, with particular strengths in migration studies, psychosocial studies, critical criminology, sexuality studies and family & childhood studies. – Philippa Grand, Publisher & Head of Social Sciences ’ Highlights from the 2013 Collection What are the benefits? • Perpetual access to purchased Collections • Unlimited, concurrent access both remotely and on site • The ability to print, copy and download without Regularly accessed titles in this subject DRM restrictions • EPUB format available for ebooks from 2011, 2012 and 2013 (in addition to PDF) for compatibility with e-readers • Simultaneous print and online publication with Social Sciences Social Sciences Social Sciences Social & Cultural Studies Social Sciences current Collections Collection 2013 Collection 2011 Collection 2011 Collection Backlist Collection 2010 updated monthly Two flexible purchase Collection Model: Over 100 collections based on subjects and years • Free MARC record Build Your Own Collections: pick titles from across subject areas and download by collection models to choose from: years to create your own collections (minimum purchase applies). -

The Bernice Summerfield Stories

www.BIGFINISH.COM • NE w AUDIO ADVENTURES THE BIG FINISH MAGAZINE FREE! THE PHILIP OLIVIER AND AMY PEMBERTON TELL US ABOUT SHARING A TARDIS! PLUS! VORTEX ISSUE 43 n September 2012 BENNY GETS BACK TO HER ROOTS IN A NEW BOX SET BERNICE SUMMERFIELD: LEGION WRITER DONALD TOSH ON HIS 1960s LOST STORY FOURTHE ROSEMARINERS COMPANIONS EDITORIAL Listen, just wanted to remind you about the Doctor Who Special Releases. What do you mean, you haven’t heard of them? SNEAK PREVIEWS AND WHISPERS It’s a special bundle of low-priced but excessively exciting new releases. The package consists of two box sets: Doctor Who: Dark Lalla Ward, Louise Jameson and Eyes (featuring the Eighth Doctor and the Daleks), UNIT: Dominion Seán Carlsen return to studio later (featuring the Seventh Doctor and Klein). PLUS! Doctor Who: Love and this month to begin recording the War (featuring the Seventh Doctor and Bernice Summerfield). PLUS! final series of Gallifrey audio dramas Two amazing adventures for the Sixth Doctor with Jago and Litefoot for 2013. (yes, I know!), Doctor Who: Voyage to Venus and Doctor Who: Voyage Last time we heard them, Romana, to the New World. Leela and Narvin were traversing the multiverse (with K-9 and Braxiatel Now, here’s the thing: this package is an experiment in cheaper still in tow). Now they’re stranded pricing. Giving you even more value for money. If it works and it on a barbaric Gallifrey that never attracts more people to listen – and persuades any of you illegal discovered time travel… and they’re downloaders out there – then it’s a model for pricing that we will looking for an escape. -

Genesys John Peel 78339 221 2 2 Timewyrm: Exodus Terrance Dicks

Sheet1 No. Title Author Words Pages 1 1 Timewyrm: Genesys John Peel 78,339 221 2 2 Timewyrm: Exodus Terrance Dicks 65,011 183 3 3 Timewyrm: Apocalypse Nigel Robinson 54,112 152 4 4 Timewyrm: Revelation Paul Cornell 72,183 203 5 5 Cat's Cradle: Time's Crucible Marc Platt 90,219 254 6 6 Cat's Cradle: Warhead Andrew Cartmel 93,593 264 7 7 Cat's Cradle: Witch Mark Andrew Hunt 90,112 254 8 8 Nightshade Mark Gatiss 74,171 209 9 9 Love and War Paul Cornell 79,394 224 10 10 Transit Ben Aaronovitch 87,742 247 11 11 The Highest Science Gareth Roberts 82,963 234 12 12 The Pit Neil Penswick 79,502 224 13 13 Deceit Peter Darvill-Evans 97,873 276 14 14 Lucifer Rising Jim Mortimore and Andy Lane 95,067 268 15 15 White Darkness David A McIntee 76,731 216 16 16 Shadowmind Christopher Bulis 83,986 237 17 17 Birthright Nigel Robinson 59,857 169 18 18 Iceberg David Banks 81,917 231 19 19 Blood Heat Jim Mortimore 95,248 268 20 20 The Dimension Riders Daniel Blythe 72,411 204 21 21 The Left-Handed Hummingbird Kate Orman 78,964 222 22 22 Conundrum Steve Lyons 81,074 228 23 23 No Future Paul Cornell 82,862 233 24 24 Tragedy Day Gareth Roberts 89,322 252 25 25 Legacy Gary Russell 92,770 261 26 26 Theatre of War Justin Richards 95,644 269 27 27 All-Consuming Fire Andy Lane 91,827 259 28 28 Blood Harvest Terrance Dicks 84,660 238 29 29 Strange England Simon Messingham 87,007 245 30 30 First Frontier David A McIntee 89,802 253 31 31 St Anthony's Fire Mark Gatiss 77,709 219 32 32 Falls the Shadow Daniel O'Mahony 109,402 308 33 33 Parasite Jim Mortimore 95,844 270 -

Full Circle Sampler

The Black Archive #15 FULL CIRCLE SAMPLER By John Toon Second edition published February 2018 by Obverse Books Cover Design © Cody Schell Text © John Toon, 2018 Range Editors: James Cooray Smith, Philip Purser-Hallard John would like to thank: Phil and Jim for all of their encouragement, suggestions and feedback; Andrew Smith for kindly giving up his time to discuss some of the points raised in this book; Matthew Kilburn for using his access to the Bodleian Library to help me with my citations; Alex Pinfold for pointing out the Blake’s 7 episode I’d overlooked; Jo Toon and Darusha Wehm for beta reading my first draft; and Jo again for giving me the support and time to work on this book. John Toon has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding, cover or e-book other than which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher. 2 For you. Yes, you! Go on, you deserve it. 3 Also Available The Black Archive #1: Rose by Jon Arnold The Black Archive #2: The Massacre by James Cooray Smith The Black Archive #3: The Ambassadors of Death by LM Myles The Black Archive #4: Dark Water / Death in Heaven by Philip Purser-Hallard The Black Archive #5: Image of the Fendahl -

ABC's Doctor Quick

The Wall of Lies Number 128 Newsletter established 1991, club formed June first 1980 The newsletter of the South Australian Doctor Who Fan Club Inc., also known as SFSA STATE Adelaide, January--February 2011 WEATHER: Warmer Free Queensland flooded, fake reporter sad by staff writers “Barcelona Tonight” reporter’s loss saddens nation TRAGEDY HAS struck in Queensland, with floods covering the state, killing many, destroying infrastructure and homes, and laying waste to abut half of the nation’s food crops. Almost overlooked in the midst of this was a very personal loss for Seven’s David Richardson. The veteran news reporter forgot to remove his Italian loafers before wading knee deep in the flood waters for the all important “reporter knee deep in flood waters” live cross. While Anna Bligh hasn’t directly addressed O Richardson’s loss, he was hopeful to draw com- ut t N No Ruined loafers were similar to pensation from the State’s emergency fund. We ow ! these, but not actually these. can only wish him the best of luck, because he wouldn’t lie about something like that. ABC’s Doctor Quick by staff writers Will series six screen on the same day in the UK and Australia? ABC1’s Boxing Day broadcast of A Christmas Carol demonstrated the Chameleon Factor # 80 Corporation can get Doctor Who episodes within a day of BBC premiere (due to the time difference it was only fifteen and a half hours after the BBC O u N t premiere). No ow ! This quick turnaround has been attributed by commentators as an attempt to prevent illegal downloading, however ABC maintain it was simply con- venient to show a Christmas themed episode close to the holiday. -

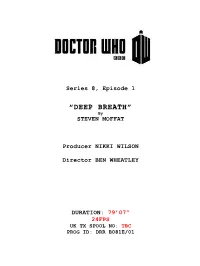

Series 8, Episode 1

Series 8, Episode 1 “DEEP BREATH” By STEVEN MOFFAT Producer NIKKI WILSON Director BEN WHEATLEY DURATION: 79’07” 24FPS UK TX SPOOL NO: TBC PROG ID: DRR B081E/01 DOCTOR WHO - POST PRODUCTION SCRIPT – SERIES 8 10:00:00 EXT. SKY - DAY A beautiful blue sky - no clue where this is. A huge, thunderous impact, earth-shaking - and now, swaying into view the head of a Tyrannosaurus Rex. It roars, it sways its mighty head - And now another sound. The tolling of bell. The Tyrannosaurus, looking around. Now bending to investigate this strange noise. Panning down with the mighty to discover the clock tower of Big Ben. Now there are the cries of terrified Londoners, screams and yells. CUT TO: 10:00:21 EXT. BANKS OF THE THAMES - DAY A row of terrified Victorian Bobbies, cordoning off gob-smacked members of the public. The screams continue, and we see their view of the Tyrannosaur dwarfing Big Ben. At the front is jaw-dropped Inspector Gregson, staring up at the impossible creature. Pushing their way, through the garden, comes the Veiled Detective herself - Madame Vastra. Following, Jenny Flint and Strax. 10:00:37 INSPECTOR GREGSON Madame Vastra, thank God. I'll wager you've not seen anything like this before! Vastra steps forward, looking up at the bellowing creature - VASTRA Well - She throws back her veil, revealing her green, reptile skin. VASTRA (cont'd) - not since I was a little girl. © BBC 2014 PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL DOCTOR WHO - POST PRODUCTION SCRIPT – SERIES 8 Jenny and Strax, stepping forward to join her. -

Thetidesoftime

The Oxford University Doctor Who Society Mag azine TThhee TTiiddeess ooff TTiimmee Issue 29 Easter Vacation 2004 BUFFY AND THE BRITISH Star Trek The Prisoner The career of Brian Clemens … …and something called Doctor Who , apparently. The Tides of Time 29 • 36 • Easter Vacation 2004 The Tides of Time 29 • 1 • Easter Vacation 2004 the difference between people and objects. The Tides of Time Shorelines When Lamia presents Grendel with her android copy of Romana, a primitive device More shorelines IIIIIIIssssssssuuueee 222999 EEEaaasssstttteeerrrr VVVaaaccccaaattttiiiiiiiooonnn 222000000444 By the Editor Well, that’s about it for now. Thank you to everyone intended to kill the Doctor, Grendel exclaims that it is a killing machine, and that he would for getting this far; unless you have started at this Editor Matthew Kilburn end of the magazine, in which case, welcome to Turn of the Tide? marry it. In doing so he discloses his [email protected]@history.oxford.ac.ukoxford.ac.uk This issue of The Tides of Time is being issue 29 of The Tides of Time ! I said a few years ago, published within a few weeks of the understanding of power, that it comprises the when I cancelled my own zine, The Troglodyte , after SubSubSub-Sub ---EditorEditor Alexandra Cameron cancellation of Angel by the WB ability to kill people. Grendel is a powerful one issue, that having got a job as an editor I didn’t Executive Editor Matthew Peacock network in the USA. The situation may man, in his own society, and at least recognises think that editing in my spare time would have much Production Associate Linda Tyrrell have moved on by the time that you the Doctor as another man of power; but the appeal. -

Doctor Who 1 Doctor Who

Doctor Who 1 Doctor Who This article is about the television series. For other uses, see Doctor Who (disambiguation). Doctor Who Genre Science fiction drama Created by • Sydney Newman • C. E. Webber • Donald Wilson Written by Various Directed by Various Starring Various Doctors (as of 2014, Peter Capaldi) Various companions (as of 2014, Jenna Coleman) Theme music composer • Ron Grainer • Delia Derbyshire Opening theme Doctor Who theme music Composer(s) Various composers (as of 2005, Murray Gold) Country of origin United Kingdom No. of seasons 26 (1963–89) plus one TV film (1996) No. of series 7 (2005–present) No. of episodes 800 (97 missing) (List of episodes) Production Executive producer(s) Various (as of 2014, Steven Moffat and Brian Minchin) Camera setup Single/multiple-camera hybrid Running time Regular episodes: • 25 minutes (1963–84, 1986–89) • 45 minutes (1985, 2005–present) Specials: Various: 50–75 minutes Broadcast Original channel BBC One (1963–1989, 1996, 2005–present) BBC One HD (2010–present) BBC HD (2007–10) Picture format • 405-line Black-and-white (1963–67) • 625-line Black-and-white (1968–69) • 625-line PAL (1970–89) • 525-line NTSC (1996) • 576i 16:9 DTV (2005–08) • 1080i HDTV (2009–present) Doctor Who 2 Audio format Monaural (1963–87) Stereo (1988–89; 1996; 2005–08) 5.1 Surround Sound (2009–present) Original run Classic series: 23 November 1963 – 6 December 1989 Television film: 12 May 1996 Revived series: 26 March 2005 – present Chronology Related shows • K-9 and Company (1981) • Torchwood (2006–11) • The Sarah Jane Adventures (2007–11) • K-9 (2009–10) • Doctor Who Confidential (2005–11) • Totally Doctor Who (2006–07) External links [1] Doctor Who at the BBC Doctor Who is a British science-fiction television programme produced by the BBC.