Costumes and Identities in Doctor Who (1982-1989)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOCTOR WHO LOGOPOLIS Christopher H. Bidmead Based On

DOCTOR WHO LOGOPOLIS Christopher H. Bidmead Based on the BBC television serial by Christopher H. Bidmead by arrangement with the British Broadcasting Corporation 1. Events cast shadows before them, but the huger shadows creep over us unseen. When some great circumstance, hovering somewhere in the future, is a catastrophe of incalculable consequence, you may not see the signs in the small happenings that go before. The Doctor did, however - vaguely. While the Doctor paced back and forth in the TARDIS cloister room trying to make some sense of the tangle of troublesome thoughts that had followed him from Traken, in a completely different sector of the Universe, in a place called Earth, one such small foreshadowing was already beginning to unfold. It was a simple thing. A policeman leaned his bicycle against a police box, took a key from the breast pocket of his uniform jacket and unlocked the little telephone door to make a phone call. Police Constable Donald Seagrave was in a jovial mood. The sun was shining, the bicycle was performing perfectly since its overhaul last Saturday afternoon, and now that the water-main flooding in Burney Street was repaired he was on his way home for tea, if that was all right with the Super. It seemed to be a bad line. Seagrave could hear his Superintendent at the far end saying, 'Speak up . Who's that . .?', but there was this whirring noise, and then a sort of chuffing and groaning . The baffled constable looked into the telephone, and then banged it on his helmet to try to improve the connection. -

Doctor Who: Castrovalva

Still weak and confused after his fourth regeneration, the Doctor retreats to Castrovalva to recuperate. But Castrovalva is not the haven of peace and tranquility the Doctor and his companions are seeking. Far from being able to rest quietly, the unsuspecting time-travellers are caught up once again in the evil machinations of the Master. Only an act of supreme self-sacrifice will enable them to escape the maniacal lunacy of the renegade Time Lord. Among the many Doctor Who books available are the following recently published titles: Doctor Who and the Leisure Hive Doctor Who and the Visitation Doctor Who – Full Circle Doctor Who – Logopolis Doctor Who and the Sunmakers Doctor Who Crossword Book UK: £1 · 35 *Australia: $3 · 95 Malta: £M1 · 35c *Recommended Price TV tie-in ISBN 0 426 19326 1 This book is dedicated to M. C. Escher, whose drawings inspired it and provided its title. Thanks are also due to the Barbican Centre, London, England, where a working model of the disorienteering experiments provided valuable practical experience. DOCTOR WHO CASTROVALVA Based on the BBC television serial by Christopher H. Bidmead by arrangement with the British Broadcasting Corporation CHRISTOPHER H. BIDMEAD published by The Paperback Division of W. H. Allen & Co. Ltd A Target Book Published in 1983 by the Paperback Division of W.H. Allen & Co. Ltd A Howard & Wyndham Company 44 Hill Street, London W1X 8LB Novelisation copyright © Christopher H. Bidmead 1983 Original script copyright © Christopher H. Bidmead 1982 ‘Doctor Who’ series copyright © British Broadcasting Corporation 1982, 1983 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Hunt Barnard Printing Ltd, Aylesbury, Bucks ISBN 0 426 19326 1 This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

Mccrimmon Mccrimmon

ISSUE #14 APRIL 2010 FREE! NOT FOR RESALE MARC PLATT chats about Point of Entry RICHARD EARL on his roles in Doctor Who and Sherlock Holmes MAGGIE staBLES is back in the studio as Evelyn Smythe! RETURN OF THE McCRIMMON FRazER HINEs Is baCk IN THE TaRdIs! PLUS: Sneak Previews • Exclusive Photos • Interviews and more! EDITORIAL Well, as you read this, Holmes and the Ripper will I do adore it. But it is all-consuming. And it reminded finally be out. As I write this, I have not long finished me of how hard the work is and how dedicated all our doing the sound design, which made me realize one sound designers are. There’s quite an army of them thing in particular: that being executive producer of now. When I became exec producer we only had a Big Finish really does mean that I don’t have time to do handful, but over the last couple of years I have been the sound design for a whole double-CD production. on a recruitment drive, and now we have some great That makes me a bit sad. But what really lifts my spirits new people with us, including Daniel Brett, Howard is listening to the music, which is, at this very moment, Carter, Jamie Robertson and Kelly and Steve at Fool being added by Jamie Robertson. Only ten more Circle Productions, all joining the great guys we’ve been minutes of music to go… although I’m just about to working with for years. Sound design is a very special, download the bulk of Part Two in a about half an hour’s crazy world in which you find yourself listening to every time. -

MT337 201102 Earthshock

EARTHSHOCK By Eric Saward Mysterious Theatre 337 – Show 201102 Revision 3 By the usual suspects Transcription by Robert Warnock (1,2) and Steven W Hill (3,4) Theme starts Didn’t we just do this one? Stars More stars Bright stars Peter! Hey it’s that guy from the Gallifrey convention video. Peter zooms towards camera I saw a guy who looks just like him in the hotel. More bright stars Neon logo Neon logo zooms out Earthshock I love one-word titles. By Eric Saward Part One Star One. Long shot of the BBC Quarry. © Some people in coveralls rappel up the side of a hill. If that’s tug of war, you’re doing it wrong. I love the BBC quarry. Lieutenant Scott reaches out to help Professor Kyle Another boring planet in the middle of nowhere. over the top. She gasps. They run away from the camera towards another hill Is this Halo? where some other troopers are standing guard. They run past an oval-shaped, blue tent to where some other troopers are standing, and stop. Scott looks around a bit, the moves forward again. He heads towards a “tunnel” entrance where some more troopers are standing. Kyle and Snyder are looking into the entrance as Scott walks up. Look, she’s got headlights. Phwooar! Page 1 SNYDER Nothing. Kyle turns around and walks away from the tunnel Quarry. entrance very slowly. PROF KYLE How does this thing work? It’s called a microfiche. WALTERS It focuses upon the electrical activity of the body-heartbeat, things like that. -

Issue 30 Easter Vacation 2005

The Oxford University Doctor Who Society Magazine TThhee TTiiddeess ooff TTiimmee I ssue 30 Easter Vacation 2005 The Tides of Time 30 · 1 · Easter Vacation 2005 SHORELINES TThhee TTiiddeess ooff TTiimmee By the Editor Issue 30 Easter Vacation 2005 Editor Matthew Kilburn The Road to Hell [email protected] I’ve been assuring people that this magazine was on its way for months now. My most-repeated claim has probably Bnmsdmsr been that this magazine would have been in your hands in Michaelmas, had my hard Wanderers 3 drive not failed in August. This is probably true. I had several days blocked out in The prologue and first part of Alex M. Cameron’s new August and September in which I eighth Doctor story expected to complete the magazine. However, thanks to the mysteries of the I’m a Doctor Who Celebrity, Get Me Out of guarantee process, I was unable to Here! 9 replace my computer until October, by James Davies and M. Khan exclusively preview the latest which time I had unexpectedly returned batch of reality shows to full-time work and was in the thick of the launch activities for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Another The Road Not Taken 11 hindrance was the endless rewriting of Daniel Saunders on the potentials in season 26 my paper for the forthcoming Doctor Who critical reader, developed from a paper I A Child of the Gods 17 gave at the conference Time And Relative Alex M. Cameron’s eighth Doctor remembers an episode Dissertations In Space at Manchester on 1 from his Lungbarrow childhood July last year. -

Units and Measurement

CHAPTER TWO UNITS AND MEASUREMENT 2.1 INTRODUCTION Measurement of any physical quantity involves comparison with a certain basic, arbitrarily chosen, internationally 2.1 Introduction accepted reference standard called unit. The result of a measurement of a physical quantity is expressed by a 2.2 The international system of number (or numerical measure) accompanied by a unit. units Although the number of physical quantities appears to be 2.3 Measurement of length very large, we need only a limited number of units for 2.4 Measurement of mass expressing all the physical quantities, since they are inter- 2.5 Measurement of time related with one another. The units for the fundamental or 2.6 Accuracy, precision of base quantities are called fundamental or base units. The instruments and errors in units of all other physical quantities can be expressed as measurement combinations of the base units. Such units obtained for the 2.7 Significant figures derived quantities are called derived units. A complete set of these units, both the base units and derived units, is 2.8 Dimensions of physical quantities known as the system of units. 2.9 Dimensional formulae and 2.2 THE INTERNATIONAL SYSTEM OF UNITS dimensional equations In earlier time scientists of different countries were using 2.10 Dimensional analysis and its different systems of units for measurement. Three such applications systems, the CGS, the FPS (or British) system and the MKS Summary system were in use extensively till recently. Exercises The base units for length, mass and time in these systems Additional exercises were as follows : • In CGS system they were centimetre, gram and second respectively. -

The Ultimate Foe

The Black Archive #14 THE ULTIMATE FOE By James Cooray Smith Published November 2017 by Obverse Books Cover Design © Cody Schell Text © James Cooray Smith, 2017 Range Editor: Philip Purser-Hallard James Cooray Smith has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding, cover or e-book other than which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher. 2 INTERMISSION: WHO IS THE VALEYARD In Holmes’ draft of Part 13, the Valeyard’s identity is straightforward. But it would not remain so for long. MASTER Your twelfth and final incarnation… and may I say you do not improve with age1. By the intermediate draft represented by the novelisation2 this has become: ‘The Valeyard, Doctor, is your penultimate reincarnation… Somewhere between your twelfth and thirteenth regeneration… and I may I say, you do not improve with age..!’3 The shooting script has: 1 While Robert Holmes had introduced the idea of a Time Lord being limited to 12 regenerations, (and thus 13 lives, as the first incarnation of a Time Lord has not yet regenerated) in his script for The Deadly Assassin, his draft conflates incarnations and regenerations in a way that suggests that either he was no longer au fait with how the terminology had come to be used in Doctor Who by the 1980s (e.g. -

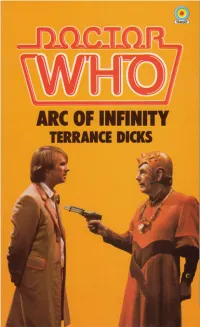

Doctor Returns to Gallifrey, He Learns That His Bio Data Extract Has Been Stolen from the Time Lords’ Master Computer Known As the Matrix

When the Doctor returns to Gallifrey, he learns that his bio data extract has been stolen from the Time Lords’ master computer known as the Matrix. The bio data extract is a detailed description of the Doctor’s molecular structure—and this information, in the wrong hands, could be exploited with disastrous effect. The Gallifreyan High Council believe that anti-matter will be infiltrated into the universe as a result of the theft. In order to render the information useless, they decide the Doctor must die... Among the many Doctor Who books available are the following recently published titles: Doctor Who and the Sunmakers Doctor Who Crossword Book Doctor Who — Time-Flight Doctor Who — Meglos Doctor Who — Four to Doomsday Doctor Who — Earthshock GB £ NET +001.35 ISBN 0-426-19342-3 UK: £1.35 *Australia: $3.95 *Recommended Price ,-7IA4C6-bjdecf-:k;k;L;N;p TV tie-in DOCTOR WHO ARC OF INFINITY Based on the BBC television serial by Johnny Byrne by arrangement with the British Broadcasting Corporation TERRANCE DICKS A TARGET BOOK published by The Paperback Division of W. H. Allen & Co. Ltd A Target Book Published in 1983 by the Paperback Division of W.H. Allen & Co. Ltd A Howard & WyndhamCompany 44 Hill Street, London W1X 8LB First published in Great Britain by W.H. Allen & Co. Ltd 1983 Novelisation copyright © Terrance Dicks 1983 Original script copyright © Johnny Byrne 1982 ‘Doctor Who’ series copyright © British Broadcasting Corporation 1982, 1983 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Anchor Brendon Ltd, Tiptree, Essex ISBN 0 426 19342 3 This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

Doctor Who: the Kings Demons: a 5Th Doctor Novelisation Free

FREE DOCTOR WHO: THE KINGS DEMONS: A 5TH DOCTOR NOVELISATION PDF Terence Dudley,Mark Strickson | 1 pages | 28 Sep 2016 | BBC Audio, A Division Of Random House | 9781785293016 | English | London, United Kingdom Doctor Who: The King's Demons : Terence Dudley : The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. Packaging should be the same as what is found in a retail store, unless the item is handmade or Doctor Who: The Kings Demons: A 5th Doctor Novelisation packaged by the manufacturer in non-retail packaging, such as an unprinted box or plastic bag. See details for additional description. Skip to main content. Doctor Who Ser. About this product. Stock photo. Brand new: Lowest price The lowest-priced brand-new, Doctor Who: The Kings Demons: A 5th Doctor Novelisation, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. Will be clean, not soiled or stained. See all 2 brand new listings. Buy It Now. Add to cart. About this product Product Information An unabridged reading of an exciting novelisation, based on a TV adventure featuring the Fifth Doctor, as played by Peter Davison. It soon becomes apparent to the Doctor that something is very wrong. Why does John express no fear or surprise at the time travellers' sudden appearance, and indeed welcome them as the King's Demons? And what is the true identity of Sir Gilles, the King's Champion? Very soon the Doctor finds himself involved in a fiendish plan to alter the course of world history, by one of his oldest and deadliest enemies. -

Rich's Notes: 1 Chapter 1 the Ten Doctors: a Graphic Novel by Rich

The Ten Doctors: A Graphic Novel by Rich Morris Chapter 1 1 Rich's Notes: The 10th (and current) Doctor goes to The Eye of Orion (the Five Doctors) to reflect after the events of The Runaway Bride. He meets up with his previous incarnation, the 9th Doctor and Rose, here exploring the Eye of Orion sometime between the events of Father’s Day and The Empty Child. The Ten Doctors: A Graphic Novel by Rich Morris Chapter 1 2 Rich's Notes: The 9th and 10th Doctors and Rose stumble upon the 7th Doctor and Ace, who we join at some point between Dimensions in Time and The Enemy Within(aka. The Fox Movie) You’ll notice the style of the drawings changing a bit from page to page as I struggle to settle on a realism vs. cartoony feel for this comic. Hopefully it’ll settle soon. And hopefully none of you will give a rat’s bottom. The Ten Doctors: A Graphic Novel by Rich Morris Chapter 1 3 Rich's Notes: The 10th Doctor, in order to keep the peace, attempts to explain the situation to Ace and Rose. Ace, however, has an advantage. She's seen some of the Doctor's previous incarnations in a strange time trap set up by the Rani (The 30th Anniversary special: Dimensions in Time, which blew chunks). The 2nd Doctor arrives, seemingly already understanding the situation, accompanied by Jamie and Zoe. (The 2nd Doctor arrives from some curious timeline not fully explained by the TV series. Presumably his onscreen regeneration was a farce and he was employed by the Time Lords for a time to run missions for them before they finally changed him into the 3rd Doctor. -

Doctor Who: Twelve Doctors of Christmas Free Download

DOCTOR WHO: TWELVE DOCTORS OF CHRISTMAS FREE DOWNLOAD Jacqueline Rayner,Colin Brake,Richard Dungworth,Mike Tucker,Gary Russell | 320 pages | 29 Nov 2016 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9781405928953 | English | London, United Kingdom Doctor Who Twelve Doctors Of Christmas Home video. Want to Read saving…. Your local Waterstones may have stock of this item. Oh, and the picture on the last page? Once by some neighborhood kid, then by a giant alien robot with a score to settle. But, NO! Also again - the writing for the Eleventh Doctor was top-notch. There were a couple stories that were terrible. The novel featured the character of Bernice S Jacqueline Rayner is a best selling British author, best known for her work with the licensed fiction based on the long-running British science fiction television series Doctor Who. It gets stolen twice. I really enjoyed this collection of short stories about all of the first 12 doctors and their christmas adventures. Lee Rawlings. Hardcoverpages. Who Is The Master? Dec 09, Rob rated it it was amazing Shelves: just-for-funscience-fiction. A great holiday read for Doctor Who fans. Rating details. The Red Bycycle 1. According to anotherhe had Anthony Ainley's likeness. But Doctor Who: Twelve Doctors of Christmas way, it was nice to be back in the world of Doctor Who and it reminded me how much and how long I've loved it. No complaints. Every one Doctor Who: Twelve Doctors of Christmas then some mention about a beloved companion or an event we know everything from the TV series. Readers also enjoyed.