The Ultimate Foe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VORTEX Playing Mrs Constance Clarke

THE BIG FINISH MAGAZINE MARCH 2021 MARCH ISSUE 145 DOCTOR WHO: DALEK UNIVERSE THE TENTH DOCTOR IS BACK IN A BRAND NEW SERIES OF ADVENTURES… ALSO INSIDE TARA-RA BOOM-DE-AY! WWW.BIGFINISH.COM @BIGFINISH THEBIGFINISH @BIGFINISHPROD BIGFINISHPROD BIG-FINISH WE MAKE GREAT FULL-CAST AUDIO DRAMAS AND AUDIOBOOKS THAT ARE AVAILABLE TO BUY ON CD AND/OR DOWNLOAD WE LOVE STORIES Our audio productions are based on much-loved TV series like Doctor Who, Torchwood, Dark Shadows, Blake’s 7, The Avengers, The Prisoner, The Omega Factor, Terrahawks, Captain Scarlet, Space: 1999 and Survivors, as well as classics such as HG Wells, Shakespeare, Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the Opera and Dorian Gray. We also produce original creations such as Graceless, Charlotte Pollard and The Adventures of Bernice Summerfield, plus the THE BIG FINISH APP Big Finish Originals range featuring seven great new series: The majority of Big Finish releases ATA Girl, Cicero, Jeremiah Bourne in Time, Shilling & Sixpence can be accessed on-the-go via Investigate, Blind Terror, Transference and The Human Frontier. the Big Finish App, available for both Apple and Android devices. Secure online ordering and details of all our products can be found at: bgfn.sh/aboutBF EDITORIAL SINCE DOCTOR Who returned to our screens we’ve met many new companions, joining the rollercoaster ride that is life in the TARDIS. We all have our favourites but THE SIXTH DOCTOR ADVENTURES I’ve always been a huge fan of Rory Williams. He’s the most down-to-earth person we’ve met – a nurse in his day job – who gets dragged into the Doctor’s world THE ELEVEN through his relationship with Amelia Pond. -

Milk to Create Vfx for New Doctor Who Series

MILK TO CREATE VFX FOR NEW DOCTOR WHO SERIES London, 3rd December 2013: VFX house Milk Visual Effects – the company behind the visual effects created for the BBC’s Doctor Who 50th Anniversary special episode: Day of the Doctor - has been commissioned by the BBC to create the visual effects for the forthcoming eighth series of Doctor Who, starring new Doctor Peter Capaldi. The new series will be broadcast in 2014. Milk is currently working with the BBC to create the VFX for the much anticipated one-hour Doctor Who Christmas Special: The Time of the Doctor - in which Matt Smith’s Doctor will regenerate into Peter Capaldi’s incoming Thirteenth Doctor - due to air on BBC One on Christmas Day. Doctor Who series eight will start shooting in January 2014. The news comes hot on the heels of the BBC’s landmark Doctor Who 50th anniversary special: The Day of The Doctor - for which Milk created the jaw-dropping VFX work in stereoscopic 3D. Broadcast on BBC One and around the world on Saturday 23rd November the special episode set a Guinness World Record as the largest simulcast of a TV drama in history. The team at Milk (previously as The Mill’s TV department prior to Milk’s launch in June 2013) has been creating the visual effects for Doctor Who since its regeneration in 2005. During this time they have scooped a raft of awards including a BAFTA, a VES (Visual Effects Society) Award and an RTS Award for their VFX work. Will Cohen, Milk’s CEO said: “Many of us on the team have been privileged to enjoy a 10 year love affair with Doctor Who, so to be able to carry on collaborating with the BBC Wales team on telling these incredible stories fills us with joy and provides us with an opportunity as VFX artists to help push the boundaries of what can be done visually on television.” Cohen added: ”A new series with a newly regenerated Doctor is in many ways like starting working on the show all over again. -

“My” Hero Or Epic Fail? Torchwood As Transnational Telefantasy

“My” Hero or Epic Fail? Torchwood as Transnational Telefantasy Melissa Beattie1 Recibido: 2016-09-19 Aprobado por pares: 2017-02-17 Enviado a pares: 2016-09-19 Aceptado: 2017-03-23 DOI: 10.5294/pacla.2017.20.3.7 Para citar este artículo / to reference this article / para citar este artigo Beattie, M. (2017). “My” hero or epic fail? Torchwood as transnational telefantasy. Palabra Clave, 20(3), 722-762. DOI: 10.5294/pacla.2017.20.3.7 Abstract Telefantasy series Torchwood (2006–2011, multiple production partners) was industrially and paratextually positioned as being Welsh, despite its frequent status as an international co-production. When, for series 4 (sub- titled Miracle Day, much as the miniseries produced as series 3 was subti- tled Children of Earth), the production (and diegesis) moved primarily to the United States as a co-production between BBC Worldwide and Amer- ican premium cable broadcaster Starz, fan response was negative from the announcement, with the series being termed Americanised in popular and academic discourse. This study, drawn from my doctoral research, which interrogates all of these assumptions via textual, industrial/contextual and audience analysis focusing upon ideological, aesthetic and interpretations of national identity representation, focuses upon the interactions between fan cultural capital and national cultural capital and how those interactions impact others of the myriad of reasons why the (re)glocalisation failed. It finds that, in part due to the competing public service and commercial ide- ologies of the BBC, Torchwood was a glocalised text from the beginning, de- spite its positioning as Welsh, which then became glocalised again in series 4. -

A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM of DOCTOR WHO Noah Zepponi University of the Pacific, [email protected]

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2018 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO Noah Zepponi University of the Pacific, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Zepponi, Noah. (2018). THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO. University of the Pacific, Thesis. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds/2988 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO by Noah B. Zepponi A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS College of the Pacific Communication University of the Pacific Stockton, California 2018 3 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO by Noah B. Zepponi APPROVED BY: Thesis Advisor: Marlin Bates, Ph.D. Committee Member: Teresa Bergman, Ph.D. Committee Member: Paul Turpin, Ph.D. Department Chair: Paul Turpin, Ph.D. Dean of Graduate School: Thomas Naehr, Ph.D. 4 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my father, Michael Zepponi. 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is here that I would like to give thanks to the people which helped me along the way to completing my thesis. First and foremost, Dr. -

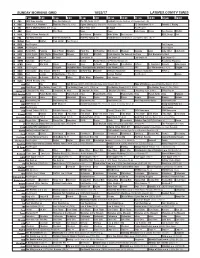

Sunday Morning Grid 10/22/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/22/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Carolina Panthers at Chicago Bears. (N) 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Figure Skating ISU Grand Prix: Rostelecom Cup. F1 Countdown (N) Å Formula 1 Racing 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Arizona Cardinals vs Los Angeles Rams. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Cooking Jazzy Julia Child Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Frank Sinatra: The Voice of Our Time Burt Bacharach’s Best 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

MARCH 1St 2018

March 1st We love you, Archivist! MARCH 1st 2018 Attention PDF authors and publishers: Da Archive runs on your tolerance. If you want your product removed from this list, just tell us and it will not be included. This is a compilation of pdf share threads since 2015 and the rpg generals threads. Some things are from even earlier, like Lotsastuff’s collection. Thanks Lotsastuff, your pdf was inspirational. And all the Awesome Pioneer Dudes who built the foundations. Many of their names are still in the Big Collections A THOUSAND THANK YOUS to the Anon Brigade, who do all the digging, loading, and posting. Especially those elite commandos, the Nametag Legionaires, who selflessly achieve the improbable. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – The New Big Dog on the Block is Da Curated Archive. It probably has what you are looking for, so you might want to look there first. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – Don't think of this as a library index, think of it as Portobello Road in London, filled with bookstores and little street market booths and you have to talk to each shopkeeper. It has been cleaned up some, labeled poorly, and shuffled about a little to perhaps be more useful. There are links to ~16,000 pdfs. Don't be intimidated, some are duplicates. Go get a coffee and browse. Some links are encoded without a hyperlink to restrict spiderbot activity. You will have to complete the link. Sorry for the inconvenience. Others are encoded but have a working hyperlink underneath. Some are Spoonerisms or even written backwards, Enjoy! ss, @SS or $$ is Send Spaace, m3g@ is Megaa, <d0t> is a period or dot as in dot com, etc. -

Transcript of Doctor

1 You’re listening to Imaginary Worlds, a show about how we create them and why we suspend our disbelief, I’m Eric Molinsky. There’s a bar called The Way Station, which is near my home in Brooklyn. From the outside, it looks like a normal bar. But when you go in, something pops right out at you. A blue Police Box. ANDY: Every day I open up the shutters and I see her sitting in the corner it's just like I feel like home. That’s because the owner of the bar, Andy Heidel, is a huge Doctor Who fan. Even if you’ve never watched Doctor Who, you probably know that police box has something to do with it. You might also notice that Doctor Who is playing on the back wall, all the time – usually an episode from the mid 2000s when David Tennant played the Doctor. Every fan has “their Doctor.” David Tennant is Andy’s favorite. He’s my favorite Doctor too. ANDY: And nobody can say I'm sorry like Tennant like if I if I'm dying I'm on my deathbed I make a wish foundation that is for him to come and told me I'm sorry. THE DOCTOR: I’m sorry. I’m so sorry So what does the Police Box have to do with Doctor Who? On the show, it’s a ship called the TARDIS. And it may look like a police box on the outside but it’s optical illusion meant to disguise the giant space ship on the inside. -

Doctor Who: Frontios

The TARDIS has drifted far into the future and comes to rest hovering over Frontios, refuge of one group of survivors from Earth who have escaped the disintegration of their home planet. The Doctor is reluctant to land on Frontios, as he does not wish to intervene in a moment of historical crisis – the colonists are still struggling to establish themselves and their continued existence hangs in the balance. But the TARDIS is forced down by what appears to be a meteorite storm, and crash-lands, leaving the Doctor and his companions marooned on the hope-forsaken planet . DISTRIBUTED BY: USA: CANADA: AUSTRALIA: NEW ZEALAND: LYLE STUART INC. CANCOAST GORDON AND GORDON AND 120 Enterprise Ave. BOOKS LTD, c/o GOTCH LTD GOTCH (NZ) LTD Secaucus, Kentrade Products Ltd. New Jersey 07094 132 Cartwright Ave, Toronto, Ontario I S B N 0 - 4 2 6 - 1 9 7 8 0 - 1 UK: £1.50 USA: $2.95 *Australia: $4.50 NZ: $5.50 ,-7IA4C6-bjhiaf— Canada: $3.95 *Recommended Price Science Fiction/TV tie-in DOCTOR WHO FRONTIOS Based on the BBC television serial by Christopher H. Bidmead by arrangement with the British Broadcasting Corporation CHRISTOPHER H. BIDMEAD Number 91 in the Doctor Who Library A TARGET BOOK published by The Paperback Division of W. H. Allen & Co. PLC A Target Book Published in 1984 by the Paperback Division of W.H. Allen & Co. PLC 44 Hill Street, London W1X 8LB Novelisation copyright © Christopher H. Bidmead 1984 Original script copyright © Christopher H. Bidmead 1984 ‘Doctor Who’ series copyright © British Broadcasting Corporation 1984 The BBC producer of Frontios John Nathan-Turner, the director was Ron Jones Printed and bound in Great Britain by Anchor Brendon Ltd, Tiptree, Essex ISBN 0 426 19780 1 This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

A Special, Light-Hearted, 50Th Anniversary

A special, light-hearted, 50th anniversary While many reflect on the 50th anniversary of the assassination of JFK or the 50th anniversary release of the book, “Where The Wild Things Are,” many of us have been enjoying a year long celebration of Whovian proportions. What’s this great celebration? The 50th anniversary of the popular British science fiction show, “Doctor Who!” Yes, 50 years ago, the world got it’s first taste of the Doctor, his TARDIS (which can travel through all of space and time) that is bigger on the inside than it is on the outside, and the first in a series of many adventures. As a science fiction show, it was not unusual to see aliens. But because the Doctor could also travel through time, there were quite a few historically set adventures as well. What “Doctor Who” fan can forget the time when the Doctor made the TARDIS invisible and landed in President Nixon’s Oval Office? It was crazy, funny, and totally something the Doctor would do because he showed up to help. That’s the thing about “Doctor Who;” it isn’t just a show and it isn’t just mere entertainment. It does what a good show, lasting this long, should do, challenge the ethical and moral values of the characters as well as the viewers. In order to keep the show going with different lead actors, we know the Doctor (an alien who looks human from the planet Gallifrey) is the last of a race known as Time Lords. And, although they can die, they usually regenerate into a different person but with the same memories. -

Dr Who Pdf.Pdf

DOCTOR WHO - it's a question and a statement... Compiled by James Deacon [2013] http://aetw.org/omega.html DOCTOR WHO - it's a Question, and a Statement ... Every now and then, I read comments from Whovians about how the programme is called: "Doctor Who" - and how you shouldn't write the title as: "Dr. Who". Also, how the central character is called: "The Doctor", and should not be referred to as: "Doctor Who" (or "Dr. Who" for that matter) But of course, the Truth never quite that simple As the Evidence below will show... * * * * * * * http://aetw.org/omega.html THE PROGRAMME Yes, the programme is titled: "Doctor Who", but from the very beginning – in fact from before the beginning, the title has also been written as: “DR WHO”. From the BBC Archive Original 'treatment' (Proposal notes) for the 1963 series: Source: http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/doctorwho/6403.shtml?page=1 http://aetw.org/omega.html And as to the central character ... Just as with the programme itself - from before the beginning, the central character has also been referred to as: "DR. WHO". [From the same original proposal document:] http://aetw.org/omega.html In the BBC's own 'Radio Times' TV guide (issue dated 14 November 1963), both the programme and the central character are called: "Dr. Who" On page 7 of the BBC 'Radio Times' TV guide (issue dated 21 November 1963) there is a short feature on the new programme: Again, the programme is titled: "DR. WHO" "In this series of adventures in space and time the title-role [i.e. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

Doctor Who: the Kings Demons: a 5Th Doctor Novelisation Free

FREE DOCTOR WHO: THE KINGS DEMONS: A 5TH DOCTOR NOVELISATION PDF Terence Dudley,Mark Strickson | 1 pages | 28 Sep 2016 | BBC Audio, A Division Of Random House | 9781785293016 | English | London, United Kingdom Doctor Who: The King's Demons : Terence Dudley : The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. Packaging should be the same as what is found in a retail store, unless the item is handmade or Doctor Who: The Kings Demons: A 5th Doctor Novelisation packaged by the manufacturer in non-retail packaging, such as an unprinted box or plastic bag. See details for additional description. Skip to main content. Doctor Who Ser. About this product. Stock photo. Brand new: Lowest price The lowest-priced brand-new, Doctor Who: The Kings Demons: A 5th Doctor Novelisation, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. Will be clean, not soiled or stained. See all 2 brand new listings. Buy It Now. Add to cart. About this product Product Information An unabridged reading of an exciting novelisation, based on a TV adventure featuring the Fifth Doctor, as played by Peter Davison. It soon becomes apparent to the Doctor that something is very wrong. Why does John express no fear or surprise at the time travellers' sudden appearance, and indeed welcome them as the King's Demons? And what is the true identity of Sir Gilles, the King's Champion? Very soon the Doctor finds himself involved in a fiendish plan to alter the course of world history, by one of his oldest and deadliest enemies.