Technology Transfers and the Arms Trade Treaty – Issues and Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coproduce Or Codevelop Military Aircraft? Analysis of Models Applicable to USAN* Brazilian Political Science Review, Vol

Brazilian Political Science Review ISSN: 1981-3821 Associação Brasileira de Ciência Política Svartman, Eduardo Munhoz; Teixeira, Anderson Matos Coproduce or Codevelop Military Aircraft? Analysis of Models Applicable to USAN* Brazilian Political Science Review, vol. 12, no. 1, e0005, 2018 Associação Brasileira de Ciência Política DOI: 10.1590/1981-3821201800010005 Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=394357143004 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Coproduce or Codevelop Military Aircraft? Analysis of Models Applicable to USAN* Eduardo Munhoz Svartman Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil Anderson Matos Teixeira Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil The creation of the Union of South American Nations (USAN) aroused expectations about joint development and production of military aircraft in South America. However, political divergences, technological asymmetries and budgetary problems made projects canceled. Faced with the impasse, this article approaches features of two military aircraft development experiences and their links with the regionalization processes to extract elements that help to account for the problems faced by USAN. The processes of adoption of the F-104 and the Tornado in the 1950s and 1970s by countries that later joined the European Union are analyzed in a comparative perspective. The two projects are compared about the political and diplomatic implications (mutual trust, military capabilities and regionalization) and the economic implications (scale of production, value chains and industrial parks). -

SP's Aviation

SP’s AN SP GUIDE PUBLICATION ED BUYER ONLY) ED BUYER AS -B A NDI I 100.00 ( ` aviationSHARP CONTENT FOR SHARP AUDIENCE www.sps-aviation.com vol 22 ISSUE 1 • 2019 CALL FOR SERIOUS ATTENTION 2019 TO WITNESS iaF’s FigHter squaDrons likely to SOME KEY inDuctions go FurtHer Down to • raFale arounD 27/29 PAGE 14 • APACHe • cHinook Hal: PAST perFECT, GLOBAL Future tense AVIATION SUMMIT a Huge step towarDs MUCH MORE... globalisation oF inDia’s PAGE 18 civil aviation IN THE NEWS F-35• 141 units contract by us DoD; • 147 units planneD procurement by japan; • 91 UNITS per YEAR PRODuction as in 2018, eXPECTED TO be RAMPED up FURTHer RNI NUMBER: DELENG/2008/24199 “In a country like India with limited support from the industry and market, initiating 50 years ago (in 1964) publishing magazines relating to Army, Navy and Aviation sectors without any interruption is a commendable job on the part of SP Guide“ Publications. By this, SP Guide Publications has established the fact that continuing quality work in any field would result in success.” Narendra Modi, Hon’ble Prime Minister of India (*message received in 2014) SP's Home Ad with Modi 2016 A4.indd 1 01/06/18 12:06 PM PUBLISHER AND EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Jayant Baranwal SENIOR EDITOR TABLE OF CONTENTS Air Marshal B.K. Pandey (Retd) DEPUTY MANAGING EDITOR Neetu Dhulia SENIOR TECHNICAL GROUP EDITOR Lt General Naresh Chand (Retd) AN SP GUIDE PUBLICATION GROUP ASSOCIATE EDITOR SP’s Vishal Thapar CONTRIBUTORS 100.00 (INDIA-BASED BUYER ONLY) BUYER 100.00 (INDIA-BASED ` aviationSHARP CONTENT FOR SHARP AUDIENCE India: Group Captain A.K. -

Seeking Autonomy: Comparative Analysis of the Japanese & South

Seeking Autonomy: Comparative Analysis of the Japanese & South Korean Defense Sectors Master’s Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Adam Gerval, B.A. Interdisciplinary East Asian Studies MA Program The Ohio State University 2016 Thesis Committee: Philip Brown, Advisor Hajime Miyazaki Youngbae Hwang Copyright by Adam Gerval 2016 Abstract The development of defense technologies has blended economic and national security policies in the postwar era. Many countries have invested heavily in defense industries as a means to stimulate economic gain and technological innovation. However, vibrant defense industries are rarely developed through autonomous production alone. They tread a slow path that often follows shortly behind economic and industrial development, and signals rising players in the international community. However, these developments are often nurtured and influenced by key allies that illuminate both partner’s international and domestic objectives. In this paper I seek to compare the overall historical development of the Japanese and South Korean defense sectors in the post-World War II era. In doing so, I will reveal their technological capabilities, methods for infusing technology into each nation’s defense sector, and finally how these transfers provided the technological foundation for developing defensive autonomy. My findings lead me to argue that the postwar development of both sectors has been path dependent upon the evolution of their diplomatic relationships with the United States. This path has been instrumental in both nations’ economic and technological ascent, but has also been determinant of their abilities and limitations to achieve capability in specific defense technologies. -

2015 Military Equipment Export Report

2015 Military Equipment Export Report Report by the Government of the Federal Republic of Germany on Its Policy on Exports of Conventional Military Equipment in 2015 Imprint Published by The Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs Federal Ministry for and Energy was awarded the audit berufundfamilie® Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi) for its family-friendly staff policy. The certificate is Public Relations Division granted by berufund familie gGmbH, an initiative of 11019 Berlin the Hertie Foundation. www.bmwi.de Text and editing Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi) Public Relations Division 11019 Berlin www.bmwi.de Design and production PRpetuum GmbH, Munich Status June 2016 This publication as well as further publications can be obtained from: Print Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs BMWi and Energy (BMWi) Public Relations This brochure is published as part of the public relations work of the E-Mail: [email protected] Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy. It is distributed free www.bmwi.de of charge and is not intended for sale. The distribution of this brochure at campaign events or at information stands run by political parties is Central procurement service: prohibited, and political party-related information or advertising shall Tel.: +49 30 182722721 not be inserted in, printed on, or affixed to this publication. Fax: +49 30 18102722721 2015 Military Equipment Export Report Report by the Government of the Federal Republic of Germany on Its Policy on Exports of Conventional Military -

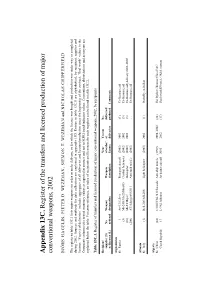

Appendix 13C. Register of the Transfers and Licensed Production of Major Conventional Weapons, 2002

Appendix 13C. Register of the transfers and licensed production of major conventional weapons, 2002 BJÖRN HAGELIN, PIETER D. WEZEMAN, SIEMON T. WEZEMAN and NICHOLAS CHIPPERFIELD The register in table 13C.1 lists major weapons on order or under delivery, or for which the licence was bought and production was under way or completed during 2002. Sources and methods for data collection are explained in appendix 13D. Entries in table 13C.1 are alphabetical, by recipient, supplier and licenser. ‘Year(s) of deliveries’ includes aggregates of all deliveries and licensed production since the beginning of the contract. ‘Deal worth’ values in the Comments column refer to real monetary values as reported in sources and not to SIPRI trend-indicator values. Conventions, abbreviations and acronyms are explained below the table. For cross-reference, an index of recipients and licensees for each supplier can be found in table 13C.2. Table 13C.1. Register of transfers and licensed production of major conventional weapons, 2002, by recipients Recipient/ Year Year(s) No. supplier (S) No. Weapon Weapon of order/ of delivered/ or licenser (L) ordered designation description licence deliveries produced Comments Afghanistan S: Russia 1 An-12/Cub-A Transport aircraft (2002) 2002 (1) Ex-Russian; aid (5) Mi-24D/Mi-25/Hind-D Combat helicopter (2002) 2002 (5) Ex-Russian; aid (10) Mi-8T/Hip-C Helicopter (2002) 2002 (3) Ex-Russian; aid; delivery 2002–2003 (200) AT-4 Spigot/9M111 Anti-tank missile (2002) . Ex-Russian; aid Albania S: Italy (1) Bell-206/AB-206 Light helicopter -

The Plan in Maturity 279 RCAF. a Fabric-Covered Biplane, with Two

The Plan in Maturity 279 RCAF. A fabric-covered biplane, with two open cockpits in tandem, it was powered by a radial air-cooled engine and had a maximum speed of I I 3 mph. He found it 'a nice, kind, little aeroplane,' though the primitive Gosport equipment used to give dual instruction in the air was 'an absolutely terrible system. It was practically a tube, a flexible tube' through which the instructor talked 'into your ears . like listening at the end of a hose. ' MacKenzie went solo after ten hours. His first solo landing was complicated. As he approached, other aircraft were taking off in front of him, forcing him to go around three times. 'I'll never get this thing on the ground, ' he thought. His feelings changed once he was down. 'It was fantastic. Full of elation.' Although they were given specific manoeuvres to fly while in the air, '99% of us went up and did aerobatics . .. instead of practising the set sequences. ' Low flying was especially exciting, 'down, kicking the tree tops, flying around just like a high speed car. ' The only disconcerting part of the course was watching a fellow pupil 'wash out. ' 'You would come back in the barracks and see some kid packing his bags, ' he remembered. 'There were no farewell parties. You packed your bags and . snuck off . It was a slight and very sad affair. ' Elementary training was followed by service instruction as either a single- or dual-engine pilot. There was no 'special fighter pilot clique' among the pupils, but MacKenzie had always wanted to fly fighters and asked for single-engine training. -

Government Support of the Large Commercial Aircraft Industries of Japan, Europe, and the United States CONTENTS Page RISK and the ROLE of GOVERNMENTS

Chapter 8 Government Support of the Large Commercial Aircraft Industries of Japan, Europe, and the United States CONTENTS Page RISK AND THE ROLE OF GOVERNMENTS . 342 UNITED STATES ... *.*. ... *.. ... ... ... ..*. ..*. ... ... *.*. *.*. .*** *. * * * 4 ...***... 344 Motives . .344 Military-Commercial Synergies . 345 Government Funding for Civil Aeronautical R&D . 346 Direct Financial Assistance . 348 promotion of a Domestic Market . 348 Export Assistance . .348 JAPAN . 349 Motives . .349 Direct Financial Supports . 349 Military-Commercial Synergies . 351 Other Mechanisms . 351 EUROPE . .352 Motives . .352 Direct Financial Support . 353 Government Influence Over Airline Procurement Decisions . 355 Government Promotion of Cooperation and Consolidation . 356 Military-Commercial Synergies . 357 Government Funding for Civil Aeronautical R&D . ..*.....**.....,,***....****.. 358 Export Assistance . .358 CONCLUSIONS . 358 Box Box Page 8-A. Airbus . .353 Figures— Figure Page 8-1. Cumulative Cash Flow for an Aircraft Project . 344 8-2. NASA Aeronautics Funding, 1959-91 . 347 8-3. World Market Share, 1970-92 Large Commercial Transport Airplane by Value of Deliveries . 352 8-4. Aircraft Inventories by Nationality of Airlines and Aircraft Manufacture, 1989 . 356 Tables Table Page 8-1. Benefits to Commercial Aircraft and Component Manufacturers of Various Types of Government Actions . 342 8-2. Aircraft Development Costs ... ... ... ... ... $.. *.*. *.. e.. **. ..*. *.. .. .+.$..+**.. 343 8-3. Launch Aid for Airbus Members . 355 8-4. Government Ownership of Major European Airlines . 356 8-5. Sales, 1989 . 357 Chapter 8 Government Support of the Large Commercial Aircraft Industries of Japan, Europe, and the United Statesl The commercial aircraft industry2 is often charac- ment on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) Agreement on terized by superlatives. It has the largest trade Trade in Civil Aircraft acknowledges this, stating surplus of any U.S. -

Multiplying the Sources LICENSED and UNLICENSED MILITARY PRODUCTION

Small Arms Survey 2007: Chapter 1 Summary Multiplying the Sources LICENSED AND UNLICENSED MILITARY PRODUCTION For the victims of armed violence, it does not really matter who produced the gun that causes their injury or death. Yet, for those seeking to prevent such violence, the producer is extremely important. New information presented in this chapter indicates that anywhere from 60 to 80 per cent of all military rifles, assault rifles, and carbines—the weapons most frequently used in modern armed conflict—are manufactured by producers that acquired the necessary technology from others. Licensed production occurs in virtually all areas of the modern economy. The motives behind it are numerous, ranging from the anticipated increase of market share and returns on investment in research and development on the part of the licensor com- pany, to the wish to develop domestic industry and decrease import dependence on the part of the licensee country. Licensed production agreements can involve many different juridical and organizational arrangements. In some cases manufacturing tech- nology is acquired without the knowledge of its original owner, i.e. production takes place without a licence. Bangladesh and Pakistan, for example, produce weapons under a licence from China, which had previously copied the product without licence from the former Soviet Union (USSR). Production know-how, once transferred, cannot be retrieved. Both licensed and unlicensed production involves the acquisition of production technology by a manufacturer that did not previously possess it. While this need not lead to an overall increase in the number of weapons produced, it does involve the dissemination of weapons production know-how to a greater number of actors. -

Arms Procurement Decision Making Volume I: China, India, Israel

6. South Korea Jong Chul Choi* I. Introduction An examination of the arms procurement decision-making process of South Korea (the Republic of Korea) reveals certain idiosyncratic features stemming from the national and international security environments and from the institu- tional process within the Ministry of National Defense (MND). Since the 1950 Korean War the security environment of South Korea has been characterized by the long-standing threat posed by North Korea (the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea). US military policy towards South Korea—based on a military alliance relationship—and US arms transfer policy have been among the most salient factors influencing the arms procurement process. The domestic political system in operation since the 1970s—charac- terized by a strong presidency and an authoritarian tradition—has made the process less transparent and accountable to the public. A key feature is the concentration of arms procurement decision-making authority in the MND and the President. Throughout the process the MND dominates other government agencies and institutions and even the National Assembly. It has the task of concluding the process and it receives interim reports at nearly every stage. The President has the final say regarding procurement programmes with budgets exceeding 5 billion won ($5.25 mil- lion).1 1 At the 1997 average exchange rate of 951 won = $1. International Financial Statistics, Mar. 1998. * The author wishes to thank J. Y. Ra, formerly Professor of Political Science, Kyung Hee Uni- versity, and currently Vice-Director of the Agency for National Security Planning, for super- vising the study in the ROK. -

Title International Networks and Aircraft Manufacture in Colonial And

International Networks and Aircraft Manufacture in Colonial and Postcolonial India -States, Title Entrepreneurs and Educational Institutions,1940-64.- Author(s) APARAJITH,RAMNATH Citation 国際武器移転史, 9: 41-59 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10291/20588 Rights Issue Date 2020-01-21 Text version publisher Type Departmental Bulletin Paper DOI https://m-repo.lib.meiji.ac.jp/ Meiji University History of Global Arms Transfer, 9 (2020), pp. 41-59 International Networks and Aircraft Manufacture in Colonial and Postcolonial India: States, Entrepreneurs and Educational Institutions, 1940-64.† APARAJITH RAMNATH* This paper examines the beginnings of aircraft manufacture and maintenance in India by exploring the early history of Hindustan Aircraft Limited (HAL)— India’s premier producer of military aircraft—from its establishment (1940) to the inauguration of its best known locally designed aircraft (1964). Scholars have seen HAL’s beginnings primarily as an instance of colonial imperatives subugating indigenous enterprise (the company was promoted by industrialist Walchand Hirachand and later taken over by the colonial government). This paper, on the other hand, emphasises the multiplicity of actors and the broader, often extra-imperial networks that played a role in HAL’s development. The plant in Bangalore was commissioned by a team of American engineers under W.D. Pawley, who would arrange for manufacturing licences, machinery and materials through his American company, Intercontinent Corporation. These American experts supervised a team of Indian engineers and technicians; the factory was run by the US Army during the latter years of World War II. Other crucial actors were the princely government of Mysore, which provided land and concessions for the factory; German and Germany-trained experts who worked in HAL’s design teams in the post-Independence period; and the Indian Institute of Science, which provided HAL with trained personnel and research facilities. -

Switzerland Country Report

SALW Guide Global distribution and visual identification Switzerland Country report https://salw-guide.bicc.de Weapons Distribution SALW Guide Weapons Distribution The following list shows the weapons which can be found in Switzerland and whether there is data on who holds these weapons: Browning M 2 G Mosin-Nagant Rifle Mod. U 1891 FIM-92 Stinger G Panzerfaust 3 (PzF 3) G FN Herstal FN MAG G Remington 870P G FN MINIMI G Saab AT4 U Glock 17 U SIG SG510-4 G N HK MP5 G SIG SG540 G Mauser K98 U SIG SG550 G Explanation of symbols Country of origin Licensed production Production without a licence G Government: Sources indicate that this type of weapon is held by Governmental agencies. N Non-Government: Sources indicate that this type of weapon is held by non-Governmental armed groups. U Unspecified: Sources indicate that this type of weapon is found in the country, but do not specify whether it is held by Governmental agencies or non-Governmental armed groups. It is entirely possible to have a combination of tags beside each country. For example, if country X is tagged with a G and a U, it means that at least one source of data identifies Governmental agencies as holders of weapon type Y, and at least one other source confirms the presence of the weapon in country X without specifying who holds it. Note: This application is a living, non-comprehensive database, relying to a great extent on active contributions (provision and/or validation of data and information) by either SALW experts from the military and international renowned think tanks or by national and regional focal points of small arms control entities. -

The Evolution of the U.S. Helicopter Industry

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 1984 The evolution of the U.S. helicopter industry. Sheil, Murray D. http://hdl.handle.net/10945/19318 DUDLEY KNOX LIBRARY NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY. CALIFORIJIA 03943 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL Monterey, California THESIS THE EVOLUTION OF THE U.S. HELICOPTER INDUSTRY by Murray D. Sheil December 1984 D. C. Boger Thesis Co- advisors: J. E. Ferris Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited T22 SECURITY CLASSIFICATION OF THIS PAGE (Wh»n Dmta Enfrod) READ INSTRUCTIONS REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE BEFORE COMPLETING FORM 1. REPORT NUMBER 2. GOVT ACCESSION NO. 3. RECIPIENT'S CATALOG NUMBER 4. TITLE (and Subtitle) 5. TYPE OF REPORT & PERIOD COVERED Master's Thesis; The Evolution of the U.S. December 1984 Helicopter Industry 6. PERFORMING ORG. REPORT NUMBER 7. AUTHORr»J 8. CONTRACT OR GRANT NUMBERC*; Murray D. Shell 9. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME AND ADDRESS 10. PROGRAM ELEMENT. PROJECT, TASK AREA a WORK Naval Postgraduate School UNIT NUMBERS Monterey, California 93943 11. CONTROLLING OFFICE NAME AND ADDRESS 12. REPORT DATE Naval Postgraduate School December 1984 Monterey, California 93943 13. NUMBER OF PAGES 248 14. MONITORING AGENCY NAME 4 ADDRESSC// d///oren( Irom Controlling Oftlca) 15. SECURITY CLASS, (of this report) 15«. DECLASSIFICATION/ DOWNGRADING SCHEDULE 16. DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT (of this Report) Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. 17. DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT (ol the abstract entered In Block 30, U dlHerent Irom Report) 18. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES 19. KEY WORDS (Continue on reverse aide If necessary and Identify by block number) Helicopters, Civil Aviation, Aircraft, Production, Aerospace Industries, Military-Industrial Complex, International, Histori- cal Review, Acquisition, Research and Development, Design and Development, Aerospace Manufacturers, Aircraft Acquisition, Sikorsky Aircraft, Hughes Helicopter, Boeing Vertol, (contd.) 20.