ID-76-23 Coproduction Programs and Licensing Arrangements in Foreign

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coproduce Or Codevelop Military Aircraft? Analysis of Models Applicable to USAN* Brazilian Political Science Review, Vol

Brazilian Political Science Review ISSN: 1981-3821 Associação Brasileira de Ciência Política Svartman, Eduardo Munhoz; Teixeira, Anderson Matos Coproduce or Codevelop Military Aircraft? Analysis of Models Applicable to USAN* Brazilian Political Science Review, vol. 12, no. 1, e0005, 2018 Associação Brasileira de Ciência Política DOI: 10.1590/1981-3821201800010005 Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=394357143004 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Coproduce or Codevelop Military Aircraft? Analysis of Models Applicable to USAN* Eduardo Munhoz Svartman Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil Anderson Matos Teixeira Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil The creation of the Union of South American Nations (USAN) aroused expectations about joint development and production of military aircraft in South America. However, political divergences, technological asymmetries and budgetary problems made projects canceled. Faced with the impasse, this article approaches features of two military aircraft development experiences and their links with the regionalization processes to extract elements that help to account for the problems faced by USAN. The processes of adoption of the F-104 and the Tornado in the 1950s and 1970s by countries that later joined the European Union are analyzed in a comparative perspective. The two projects are compared about the political and diplomatic implications (mutual trust, military capabilities and regionalization) and the economic implications (scale of production, value chains and industrial parks). -

SP's Aviation

SP’s AN SP GUIDE PUBLICATION ED BUYER ONLY) ED BUYER AS -B A NDI I 100.00 ( ` aviationSHARP CONTENT FOR SHARP AUDIENCE www.sps-aviation.com vol 22 ISSUE 1 • 2019 CALL FOR SERIOUS ATTENTION 2019 TO WITNESS iaF’s FigHter squaDrons likely to SOME KEY inDuctions go FurtHer Down to • raFale arounD 27/29 PAGE 14 • APACHe • cHinook Hal: PAST perFECT, GLOBAL Future tense AVIATION SUMMIT a Huge step towarDs MUCH MORE... globalisation oF inDia’s PAGE 18 civil aviation IN THE NEWS F-35• 141 units contract by us DoD; • 147 units planneD procurement by japan; • 91 UNITS per YEAR PRODuction as in 2018, eXPECTED TO be RAMPED up FURTHer RNI NUMBER: DELENG/2008/24199 “In a country like India with limited support from the industry and market, initiating 50 years ago (in 1964) publishing magazines relating to Army, Navy and Aviation sectors without any interruption is a commendable job on the part of SP Guide“ Publications. By this, SP Guide Publications has established the fact that continuing quality work in any field would result in success.” Narendra Modi, Hon’ble Prime Minister of India (*message received in 2014) SP's Home Ad with Modi 2016 A4.indd 1 01/06/18 12:06 PM PUBLISHER AND EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Jayant Baranwal SENIOR EDITOR TABLE OF CONTENTS Air Marshal B.K. Pandey (Retd) DEPUTY MANAGING EDITOR Neetu Dhulia SENIOR TECHNICAL GROUP EDITOR Lt General Naresh Chand (Retd) AN SP GUIDE PUBLICATION GROUP ASSOCIATE EDITOR SP’s Vishal Thapar CONTRIBUTORS 100.00 (INDIA-BASED BUYER ONLY) BUYER 100.00 (INDIA-BASED ` aviationSHARP CONTENT FOR SHARP AUDIENCE India: Group Captain A.K. -

Seeking Autonomy: Comparative Analysis of the Japanese & South

Seeking Autonomy: Comparative Analysis of the Japanese & South Korean Defense Sectors Master’s Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Adam Gerval, B.A. Interdisciplinary East Asian Studies MA Program The Ohio State University 2016 Thesis Committee: Philip Brown, Advisor Hajime Miyazaki Youngbae Hwang Copyright by Adam Gerval 2016 Abstract The development of defense technologies has blended economic and national security policies in the postwar era. Many countries have invested heavily in defense industries as a means to stimulate economic gain and technological innovation. However, vibrant defense industries are rarely developed through autonomous production alone. They tread a slow path that often follows shortly behind economic and industrial development, and signals rising players in the international community. However, these developments are often nurtured and influenced by key allies that illuminate both partner’s international and domestic objectives. In this paper I seek to compare the overall historical development of the Japanese and South Korean defense sectors in the post-World War II era. In doing so, I will reveal their technological capabilities, methods for infusing technology into each nation’s defense sector, and finally how these transfers provided the technological foundation for developing defensive autonomy. My findings lead me to argue that the postwar development of both sectors has been path dependent upon the evolution of their diplomatic relationships with the United States. This path has been instrumental in both nations’ economic and technological ascent, but has also been determinant of their abilities and limitations to achieve capability in specific defense technologies. -

Aircraft Accident Report

FILE Ma 3-3313 AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT REPORT AIRCRAFT POOL LEASING CORPORATION, LOCKHEED SUPER CONSTELLATION, .L-l049H, N6917C MIAMI, FLORIDA DECEMBER 15,1973 ADOPTED: SEPTEMBER 11, 1974 i NATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SAFETY BOARD Washington, DX. 20591 REPORT NUMBER: NTSB-AAR-74-11 TECHNICAL REPORT STANDARD TITLE PAGE / 1. Report No. 2.Governrnent Accession No. 3.Recipient's Catalog No. NTSB-AAR-74-11 4. Title and Subtitle Bureau of Aviation Safety Washington, D. C. 20591 Period Covered Aircraft Accident Report December 15, 1973 NATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SAFETY BOARD Washington, D. C. 20591 This report does not contain any new recommendations. The aircraft struck the ground 1.25 miles east of the airport and destroyed several homes, automobiles, and other property. me aircraft's occupants--three crew- members--and six persons on the ground were killed. Two others were injured slight- ly. The aircraft was destroyed by impact and fire. The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the-probable cause of this accident was overrotation of the aircraft at lift-off resulting in flight in th aerodynamic region of reversed comnd, near the stall regime, and at too low an altitude to effect recovery. The reason for the aircraft's entering this adverse flight condition could not be determined. Factors which may have contributed to the accident include: (a) Improper cargo loading, (b) a rearward mvement of unsecured cargo resulting in a center of gravity shift aft of the allowable limit, and (c) deficient crew coordination. As the result of this accident, the Safety Board has made several reconmenda- tions to the Administrator of the Federal Aviation Administration. -

Issue No. 4, Oct-Dec

VOL. 6, NO. 4, OCTOBER - DECEMBER 1979 t l"i ~ ; •• , - --;j..,,,,,,1:: ~ '<• I '5t--A SERVt(;E P\JBLICATtON Of: t.OCKH EE:O-G EORGlA COt.'PAfllV A 01Vt$10,.. or t.OCKHEEOCOAf'ORATION A SERVICE PUBLICATION OF LOCKHEED-GEORGIA COMPANY The C-130 and Special Projects Engineering A DIVISION OF Division is pleased to welcome you to a LOCKHEED CORPORATION special “Meet the Hercules” edition of Service News magazine. This issue is de- Editor voted entirely to a description of the sys- Don H. Hungate tems and features of the current production models of the Hercules aircraft, the Ad- Associate Editors Charles 1. Gale vanced C-130H, and the L-100-30. Our James A. Loftin primary purpose is to better acquaint you with these two most recently updated Arch McCleskey members of Lockheed’s distinguished family Patricia A. Thomas of Hercules airlifters, but first we’d like to say a few words about the engineering or- Art Direction & Production ganization that stands behind them. Anne G. Anderson We in the Project Design organization have the responsibility for the configuration and Vol. 6, No. 4, October-December 1979 systems operation of all new or modified CONTENTS C-130 or L-100 aircraft. During the past 26 years, we have been intimately involved with all facets of Hercules design and maintenance. Our goal 2 Focal Point is to keep the Lockheed Hercules the most efficient and versatile cargo aircraft in the world. We 0. C. Brockington, C-130 encourage our customers to communicate their field experiences and recommendations to us so that Engineering Program Manager we can pass along information which will be useful to all operators, and act on those items that would benefit from engineeringattention. -

Table of Contents Next Page

, SERVICE PUBLICATION OF OCKHEED-GEORGIA COMPANY / DIVISION OF OCKHEED CORPORATION Editor: Don H. Hungate Associate Editors: Charles I. Gale, James A. Loftin, Arch McCleskey, Patricia Thomas Art Direction and Production: Anne G. Anderson This summer marks the 25th anniversary of the first flight of the Lockheed Hercules; a Volume 6, No. 3, July - September 1979 quarter century of service to nations throughout the world! Over 1,550 Hercules (C-130s Vol. 6, No. 3, July. September 1979 and L-100) have been delivered to 44 countries. We at Lockheed are very proud of this Contents: record and the reputation the Hercules has earned. It is a reputation built on depend- ability, versatility, and durability. 2 Focal Point The Hercules is a true workhorse. Many developing countries depend on it to carry all types of cargo, from lifesaving food to road-building equipment. They carry these cargoes to remote areas that are not easily accessible by any other mode of transporta- 3 tion. An additional advantage is its ability to land and take off in incredibly short 3 Crew Door Rigging distances, even on unpaved clearings. The tasks the Hercules is capable of accomplishing are almost limitless; from hunting hurricanes, to flying mercy relief missions. It is the universal airborne platform. And it is 14 Royal Norwegian Air Force energy-efficient, using only about half the fuel a comparable jet aircraft would require. 15 One of the more interesting aspects of these 25 years is that while the external design of 15 Hydraulic Pressure Drop the aircraft has changed very little, constant improvements in systems and avionics equip- ment have made the world’s outstanding cargo airplane also among the world’s most modern. -

PROSPECTUS Lockheed Martin Corporation Offer to Exchange 4.72

OFFERING CIRCULAR--PROSPECTUS Lockheed Martin Corporation Offer to Exchange 4.72 shares of Common Stock of Martin Marietta Materials, Inc. for each share of Common Stock of Lockheed Martin Corporation ---------------- THE EXCHANGE OFFER, PRORATION PERIOD AND WITHDRAWAL RIGHTS WILL EXPIRE AT 12:00 MIDNIGHT, NEW YORK CITY TIME, ON OCTOBER 18, 1996, UNLESS THE EXCHANGE OFFER IS EXTENDED. ---------------- Lockheed Martin Corporation, a Maryland corporation ("Lockheed Martin"), has determined to distribute the shares it owns of Martin Marietta Materials, Inc., a North Carolina corporation ("Materials" or the "Company"), to Lockheed Martin stockholders by offering to exchange 4.72 shares of Common Stock of Materials, par value $.01 per share ("Materials Common Stock"), for each share tendered of Common Stock of Lockheed Martin, par value $1.00 per share ("Lockheed Martin Common Stock"), up to an aggregate of 7,913,136 shares of Lockheed Martin Common Stock tendered and exchanged, upon the terms and subject to the conditions set forth herein and in the related Letter of Transmittal (which together constitute the "Exchange Offer"). A holder of Lockheed Martin Common Stock has the right to tender all or a portion of such holder's shares of Lockheed Martin Common Stock. As of September 16, 1996, Lockheed Martin owned 37,350,000 shares of Materials Common Stock. If more than 7,913,136 shares of Lockheed Martin Common Stock are validly tendered and not withdrawn on or prior to the Expiration Date (as defined herein) of the Exchange Offer, Lockheed Martin will accept such shares for exchange on a pro rata basis as described herein. -

Volume Basis

, (" 618 FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION DECISIONS Complaint 119 FTC. IN THE MATTER OF LOCKHEED CORPORATION, ET AL. CONSENT ORDER, ETC. , IN REGARD TO ALLEGED VIOLA nON OF SEe. 7 OF THE CLAYTON ACT AND SEe. OF THE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION ACT Docket 3576. Complaint, May 1995--Decision , May 9, 1995 This consent order aJlows, among other things, the completion of the merger between Lockheed Corporation and Martin Marietta Corporation , and requires the merged firm to open up the teaming arrangements that each individual finn has with infrared sensor producers in order to restore competition for ccrtain types of military sateIlites. The consent order also prohibits certain divisions of the merged firm from gaining access through other divisions to competitively sensitive information about competitors' satellite launch vehicles or military aircraft. Appearances For the Commission: Ann B. Malester and Laura A. Wilkinson. For the respondents: Richard Parker and David Beddon, Melveny Meyers, Washington , D. e. Raymond Jacobson Howrey Simon, Washington, D. COMPLAINT Pursuant to the provisions of the Federal Trade Commission Act and by virtue of the authority vested in it by said Act, the Federal Trade Commission ("Commission ), having reason to believe that respondent Lockheed Corporation ("Lockheed" ), a corporation subject to the jurisdiction of the Commission , has agreed to merge with respondent Martin Marietta Corporation ("Martin Marietta ), a corporation subject to the jurisdiction of the Commission, forming a newly created entity respondent Lockheed Martin Corporation ("Lockheed Martin ), a corporation subject to the jurisdiction of the Commission, in violation of Section 7 of the Clayton Act , as amended, 15 U. e. 18 , and Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act as amended FTC Act ), 15 USe. -

PLRD-82-38 C-5A Wing Modification

Comptroller General OF THE UNITEDSTATES CXA Wing Modification : A Case Study Illustrating Problems In The Defense Weapons Acquisition Process The Air Force had data in 1967 indicating air- frame weight problems in the C5A aircraft’s original design. These problems eventually led Lockheed, the C5A manufacturer, to deviate from contract specifications by reducing wing material thicknesses. Not until September 1971, after accepting 40 aircraft, did the Air Force have enough test data to recognize that the C5A wing might require major structural repair or modification, On the basis of a series of analyses, DOD eventually approved the wing modification in 1975. After this, the Air Force did not evaluate the technical feasibility of other ex- isting lower cost options. GAO believes no other viable wing repair options remain at this time. Since early 1970, DOD has made several changes to its acquisition process which should enable it to deal more effectively in the future with problems such as those which occurred on the C-5A program. This report was requested by the Vice Chair- man, Subcommittee on International Trade, Finance and Security Economics, Joint Econ- omic Committee. 1111118139llllll Ill PLRD-82-38 MARCH 22,1982 Request for copies of GAO reports should be sent to: U.S. General Accounting Off ice I Document Handling and Information Services Facility P.O. Box 6015 Gaitharsburg, Md. 20760 Telephone (202) 2756241 The first five copies of individual reports are free >f charge. Additional copies of bound audit reports ara $3.25 each. Additional copies of unbound report (i.e., letter reports) and most other publications are $1.00 each, There will be a 25% discount on all orders for 100 or more copies mailed to a single address. -

2015 Military Equipment Export Report

2015 Military Equipment Export Report Report by the Government of the Federal Republic of Germany on Its Policy on Exports of Conventional Military Equipment in 2015 Imprint Published by The Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs Federal Ministry for and Energy was awarded the audit berufundfamilie® Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi) for its family-friendly staff policy. The certificate is Public Relations Division granted by berufund familie gGmbH, an initiative of 11019 Berlin the Hertie Foundation. www.bmwi.de Text and editing Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi) Public Relations Division 11019 Berlin www.bmwi.de Design and production PRpetuum GmbH, Munich Status June 2016 This publication as well as further publications can be obtained from: Print Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs BMWi and Energy (BMWi) Public Relations This brochure is published as part of the public relations work of the E-Mail: [email protected] Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy. It is distributed free www.bmwi.de of charge and is not intended for sale. The distribution of this brochure at campaign events or at information stands run by political parties is Central procurement service: prohibited, and political party-related information or advertising shall Tel.: +49 30 182722721 not be inserted in, printed on, or affixed to this publication. Fax: +49 30 18102722721 2015 Military Equipment Export Report Report by the Government of the Federal Republic of Germany on Its Policy on Exports of Conventional Military -

AC-130 GUNSHIP and ITS VARIANTS Research from 10/2010 AC-130

THE AC-130 GUNSHIP AND ITS VARIANTS Research from 10/2010 AC-130 The AC-130 gun ship’s primary missions are close air support, air interdiction and armed reconnaissance. Other missions include perimeter and point defense, escort, landing, drop and extraction zone support, forward air control, limited command and control, and combat search and rescue. These heavily armed aircraft incorporate side-firing weapons integrated with sophisticated sensor, navigation and fire control systems to provide surgical firepower or area saturation during extended periods, at night and in adverse weather. The AC-130 has been used effectively for over thirty years to take out ground defenses and targets. One drawback to using the AC-130 is that it is typically only used in night assaults because of its poor maneuverability and limited orientations relative to the target during attack. During Vietnam, gun ships destroyed more than 10,000 trucks and were credited with many life-saving close air support missions. AC-130s suppressed enemy air defense systems and attacked ground forces during Operation Urgent Fury in Grenada. This enabled the successful assault of Point Saline’s airfield via airdrop and air land of friendly forces. The gunships had a primary role during Operation Just Cause in Panama by destroying Panamanian Defense Force Headquarters and numerous command and control facilities by surgical employment of ordnance in an urban environment. As the only close air support platform in the theater, Spectres were credited with saving the lives of many friendly personnel. Both the H-models and A-models played key roles. The fighting was opened by a gunship attack on the military headquarters of the dictator of Panama and the outcome was never in doubt. -

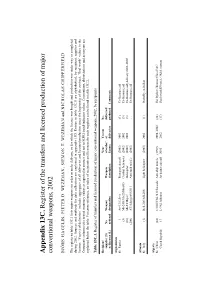

Appendix 13C. Register of the Transfers and Licensed Production of Major Conventional Weapons, 2002

Appendix 13C. Register of the transfers and licensed production of major conventional weapons, 2002 BJÖRN HAGELIN, PIETER D. WEZEMAN, SIEMON T. WEZEMAN and NICHOLAS CHIPPERFIELD The register in table 13C.1 lists major weapons on order or under delivery, or for which the licence was bought and production was under way or completed during 2002. Sources and methods for data collection are explained in appendix 13D. Entries in table 13C.1 are alphabetical, by recipient, supplier and licenser. ‘Year(s) of deliveries’ includes aggregates of all deliveries and licensed production since the beginning of the contract. ‘Deal worth’ values in the Comments column refer to real monetary values as reported in sources and not to SIPRI trend-indicator values. Conventions, abbreviations and acronyms are explained below the table. For cross-reference, an index of recipients and licensees for each supplier can be found in table 13C.2. Table 13C.1. Register of transfers and licensed production of major conventional weapons, 2002, by recipients Recipient/ Year Year(s) No. supplier (S) No. Weapon Weapon of order/ of delivered/ or licenser (L) ordered designation description licence deliveries produced Comments Afghanistan S: Russia 1 An-12/Cub-A Transport aircraft (2002) 2002 (1) Ex-Russian; aid (5) Mi-24D/Mi-25/Hind-D Combat helicopter (2002) 2002 (5) Ex-Russian; aid (10) Mi-8T/Hip-C Helicopter (2002) 2002 (3) Ex-Russian; aid; delivery 2002–2003 (200) AT-4 Spigot/9M111 Anti-tank missile (2002) . Ex-Russian; aid Albania S: Italy (1) Bell-206/AB-206 Light helicopter