International Responsibility of an Occupying Power for Environmental Harm: the Ac Se of Estonia Lisa M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Here in 2017 Sillamäe Vabatsoon 46% of Manufacturing Companies with 20 Or More Employees Were Located

Baltic Loop People and freight moving – examples from Estonia Final Conference of Baltic Loop Project / ZOOM, Date [16th of June 2021] Kaarel Kose Union of Harju County Municipalities Baltic Loop connections Baltic Loop Final Conference / 16.06.2021 Baltic Loop connections Baltic Loop Final Conference / 16.06.2021 Strategic goals HARJU COUNTY DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY 2035+ • STRATEGIC GOAL No 3: Fast, convenient and environmentally friendly connections with the world and the rest of Estonia as well as within the county. • Tallinn Bypass Railway, to remove dangerous goods and cargo flows passing through the centre of Tallinn from the Kopli cargo station; • Reconstruction of Tallinn-Paldiski (main road no. 8) and Tallinn ring road (main highway no. 11) to increase traffic safety and capacity • Indicator: domestic and international passenger connections (travel time, number of connections) Tallinn–Narva ca 1 h NATIONAL TRANSPORT AND MOBILITY DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2021-2035 • The main focus of the development plan is to reduce the environmental footprint of transport means and systems, ie a policy for the development of sustainable transport to help achieve the climate goals for 2030 and 2050. • a special plan for the Tallinn ring railway must be initiated in order to find out the feasibility of the project. • smart and safe roads in three main directions (Tallinn-Tartu, Tallinn-Narva, Tallinn-Pärnu) in order to reduce the time-space distances of cities and increase traffic safety (5G readiness etc). • increase speed on the railways to reduce time-space distances and improve safety; shift both passenger and freight traffic from road to rail and to increase its positive impact on the environment through more frequent use of rail (Tallinn-Narva connection 2035 1h45min) GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF CLIMATE POLICY UNTIL 2050 / NEC DIRECTIVE / ETC. -

The Baltic Republics

FINNISH DEFENCE STUDIES THE BALTIC REPUBLICS A Strategic Survey Erkki Nordberg National Defence College Helsinki 1994 Finnish Defence Studies is published under the auspices of the National Defence College, and the contributions reflect the fields of research and teaching of the College. Finnish Defence Studies will occasionally feature documentation on Finnish Security Policy. Views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily imply endorsement by the National Defence College. Editor: Kalevi Ruhala Editorial Assistant: Matti Hongisto Editorial Board: Chairman Prof. Mikko Viitasalo, National Defence College Dr. Pauli Järvenpää, Ministry of Defence Col. Antti Numminen, General Headquarters Dr., Lt.Col. (ret.) Pekka Visuri, Finnish Institute of International Affairs Dr. Matti Vuorio, Scientific Committee for National Defence Published by NATIONAL DEFENCE COLLEGE P.O. Box 266 FIN - 00171 Helsinki FINLAND FINNISH DEFENCE STUDIES 6 THE BALTIC REPUBLICS A Strategic Survey Erkki Nordberg National Defence College Helsinki 1992 ISBN 951-25-0709-9 ISSN 0788-5571 © Copyright 1994: National Defence College All rights reserved Painatuskeskus Oy Pasilan pikapaino Helsinki 1994 Preface Until the end of the First World War, the Baltic region was understood as a geographical area comprising the coastal strip of the Baltic Sea from the Gulf of Danzig to the Gulf of Finland. In the years between the two World Wars the concept became more political in nature: after Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania obtained their independence in 1918 the region gradually became understood as the geographical entity made up of these three republics. Although the Baltic region is geographically fairly homogeneous, each of the newly restored republics possesses unique geographical and strategic features. -

PORTS of CALL WORLDWIDE.Xlsx

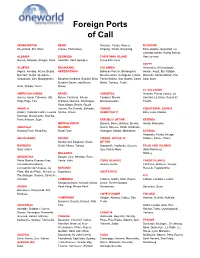

Foreign Ports of Call AFGHANISTAN BENIN Shantou, Tianjin, Xiamen, ECUADOR Kheyrabad, Shir Khan Cotnou, Porto-Novo Xingang, Yantai, Zhanjiang Esmeraoldas, Guayaquil, La Libertad, Manta, Puerto Bolivar, ALBANIA BERMUDA CHRISTMAS ISLAND San Lorenzo Durres, Sarande, Shegjin, Vlore Hamilton, Saint George’s Flying Fish Cove EGYPT ALGERIA BOSNIAAND COLOMBIA Alexandria, Al Ghardaqah, Algiers, Annaba, Arzew, Bejaia, HERZEGOVINA Bahia de Portete, Barranquilla, Aswan, Asyut, Bur Safajah, Beni Saf, Dellys, Djendjene, Buenaventura, Cartagena, Leticia, Damietta, Marsa Matruh, Port Ghazaouet, Jijel, Mostaganem, Bosanka Gradiska, Bosakni Brod, Puerto Bolivar, San Andres, Santa Said, Suez Bosanki Samac, and Brcko, Marta, Tumaco, Turbo Oran, Skikda, Tenes Orasje EL SALVADOR AMERICAN SAMOA BRAZIL COMOROS Acajutla, Puerto Cutuco, La Aunu’u, Auasi, Faleosao, Ofu, Belem, Fortaleza, Ikheus, Fomboni, Moroni, Libertad, La Union, Puerto El Pago Pago, Ta’u Imbituba, Manaus, Paranagua, Moutsamoudou Triunfo Porto Alegre, Recife, Rio de ANGOLA Janeiro, Rio Grande, Salvador, CONGO, EQUATORIAL GUINEA Ambriz, Cabinda, Lobito, Luanda Santos, Vitoria DEMOCRATIC Bata, Luba, Malabo Malongo, Mocamedes, Namibe, Porto Amboim, Soyo REPUBLIC OF THE ERITREA BRITISH VIRGIN Banana, Boma, Bukavu, Bumba, Assab, Massawa ANGUILLA ISLANDS Goma, Kalemie, Kindu, Kinshasa, Blowing Point, Road Bay Road Town Kisangani, Matadi, Mbandaka ESTONIA Haapsalu, Kunda, Muuga, ANTIGUAAND BRUNEI CONGO, REPUBLIC Paldiski, Parnu, Tallinn Bandar Seri Begawan, Kuala OF THE BARBUDA Belait, Muara, Tutong -

Integrated Review Service for Radioactive Waste and Spent Fuel Management, Decommissioning and Remediation (Artemis) Mission

INTEGRATED REVIEW SERVICE FOR RADIOACTIVE WASTE AND SPENT FUEL MANAGEMENT, DECOMMISSIONING AND REMEDIATION (ARTEMIS) MISSION TO ESTONIA TALLINN, ESTONIA 24 March to 1 April 2019 DEPARTMENT OF NUCLEAR SAFETY AND SECURITY DEPARTMENT OF NUCLEAR ENERGY REPORT OF THE INTEGRATED REVIEW SERVICE FOR RADIOACTIVE WASTE AND SPENT FUEL MANAGEMENT, DECOMMISSIONING AND REMEDIATION (ARTEMIS) MISSION TO ESTONIA ii REPORT OF THE INTEGRATED REVIEW SERVICE FOR RADIOACTIVE WASTE AND SPENT FUEL MANAGEMENT, DECOMMISSIONING AND REMEDIATION (ARTEMIS) MISSION TO ESTONIA Mission dates: 24 March to 1 April 2019 Location: Tallinn, Estonia Organized by: IAEA ARTEMIS REVIEW TEAM Ms Cherry TWEED ARTEMIS Team Leader (UK) Ms Maria Isabel F. PAIVA Reviewer (Portugal) Mr István LÁZÁR Reviewer (Hungary) Mr Stefan THEIS Reviewer (Switzerland) Mr Andrey GUSKOV IAEA Team Coordinator Mr Jiri FALTEJSEK IAEA Deputy Team Coordinator Ms Kristina NUSSBAUM IAEA Admin. Assistant IAEA-2019 iii The number of recommendations, suggestions and good practices is in no way a measure of the status of the national infrastructure for nuclear and radiation safety. Comparisons of such numbers between ARTEMIS reports from different countries should not be attempted. iv CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 1 I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 3 II. OBJECTIVE AND SCOPE ............................................................................................................ -

Doing Business and Investing in Estonia 2014 Contents

Doing business and investing in Estonia 2014 Contents Contents 6 Office location in Estonia 1 Country profile and investment climate 7 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Government structure 1.3 Legal system 1.4 People 1.5 Economy 1.6 Foreign trade 1.7 Further reading 2 Business environment 14 2.1 Business climate 2.2 Free trade zones 2.3 International agreements 2.4 Legal environment 2.5 Regulations for business 2.6 Property market 3 Banking, finance and insurance 21 3.1 Banking system 3.2 Specialised financial institutions 3.3 Investment institutions 3.4 Capital markets 4 Importing and exporting 24 4.1 Trends in customs policy 4.2 Import restrictions 4.3 Customs duties 4.4 Temporary import relief 4.5 Documentation and procedures 4.6 Warehousing and storage 4.7 Re-exports 5 Business entities 27 5.1 Legal framework 5.2 Choice of entity and business forms 5.3 Private limited company (OÜ) and public limited company (AS) 5.4 Partnerships 5.5 Branches 5.6 Representative offices 5.7 Sole proprietorship 2 Guide to doing business and investing in Estonia PwC 6 Labour relations and social security 31 6.1 Labour market 6.2 Labour relations 6.3 Working conditions 6.4 Social security system 6.5 Foreign personnel 7 Accounting and audit requirements 39 7.1 Accounting 7.2 Chart of accounts 7.3 Audit requirements 8 Tax system and administration 43 8.1 Tax system 8.2 Direct and indirect tax burden 8.3 Principal taxes 8.4 Legislative framework 8.5 Tax treaties 8.6 Tax returns and payments 8.7 Assessments 8.8 Appeals 8.9 Withholding taxes 8.10 Tax audits 8.11 Penalties -

Baltic Coastal Hiking Route

BALTIC COASTAL HIKING ROUTE TOURS WWW.COASTALHIKING.EU LATVIA / ESTONIA TOURS WHAT CAN YOU FIND 11 12 IN THE BROCHURE TABLE OF CONTENTS TALLINN 10 The brochure includes 15 hiking tours for one and multiple days (up to 16 days) in 13 Latvia and Estonia, which is part of the Baltic Coastal Hiking Route long distance 9 path (in Latvia - Jūrtaka, in Estonian - Ranniku matkarada) (E9) - the most WHAT CAN YOU COASTAL NATURE 1. THE ROCKY 2. THE GREAT 3. sLĪtere 4. ENGURE ESTONIA interesting, most scenic coastal areas of both countries, which are renowned for FIND IN THE IN LATVIA AND BEACH OF VIDZEME: WAVE SEA NATIONAL PARK NATURE PARK their natural and cultural objects. Several tours include national parks, nature BROCHURE ESTONIA Saulkrasti - Svētciems liepāja - Ventspils Mazirbe - Kolka Mērsrags - Engure SAAREMAA PÄRNU parks, and biosphere reserves, as well as UNESCO World Heritage sites. 3 p. 8 7 Every tour includes schematic tour map, provides information about the mileage to be covered within a day, level of di culty, most outstanding sightseeing objects, as GETTING THERE 2days km 6 days km 1 day km 1 day km KOLKA well as practical information about the road surface, getting to the starting point and & AROUND 52 92 23 22 3 SALACGRĪVA returning from the fi nish back to the city. USEFUL 1 p. LINKS 4 p. LATVIA 5 p. LATVIA 7 p. LATVIA 10 p. LATVIA 11 p. 1 The tours are provided for both individual travellers and small tourist groups. VENTSPILS 6 4 It is recommended to book the transport (rent a car or use public transportation), SKULTE 5 accommodation and meals in advance, as well as arrange personal and luggage 5. -

A Hiking Tour Along the West- Ern Coast Of

A HIKING TOUR ALONG THE WESTERN COAST OF ESTONIA AND THE RESORT TOWNS PALDISKI NÕVA HARBOUR TALLINN It is possible to arrange transfers and/or ROOSTA luggage transfers from one accommodation HAAPSALU 13 A HIKING TOUR place to another. PÄRNU ALONG THE WEST- DAY 1 ERN COAST OF Excursion by foot in Pärnu’s Old Town. Pärnu is a popular resort city with many cafés, live ESTONIA AND THE music, SPAs, hotels and a beautiful Old Town. We also recommend visiting beach area. RĪGA RESORT TOWNS: Bus: PÄRNU - HAAPSALU PÄRNU AND HAAPSALU (operates 1 x day, at 16.00). Accommodation in HAAPSALU. Itinerary: PÄRNU - HAAPSALU - ROOSTA - DIRHAMI - NÕVA HARBOUR - VIHTERPALU - DAY 2 DAY 3 PALDISKI - PÕLLKÜLA - TALLINN Hiking route length: ~ 80 km Excursion by foot in HAAPSALU. We Hiking ROOSTA - DIRHAMI - Duration: 6 day recommend visiting the old town of the Haapsalu resort town, Bishop’s castle mound, NÕVA HARBOUR Difficulty level: Dome Cathedral and the historic promenade 20 km with various monuments. 6 – 8 h During lunch - a bus trip to Haapsalu - PRACTICAL INFO: On this hiking route you will see the most part of the western coast of Estonia Dirhami, (getting off at the stop “Elbiku”, bus runs 2x day, 1 km walk to the Difficulty level: from Pärnu to Tallinn. You will visit Estonia’s most popular resort cities: accommodation). Pärnu and Haapsalu. You will pass along many bays, cape horns, fishermen’s Road surface: A short stretch of road villages and overgrown meadows. In the northern part you will walk along the Accommodation near Rooslepa village. -

Technical Report Art35 Estonia 2005 Final

EUROPEAN COMMISSION DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR ENERGY AND TRANSPORT Directorate H – Nuclear Energy Radiation protection TECHNICAL REPORT VERIFICATIONS UNDER THE TERMS OF ARTICLE 35 OF THE EURATOM TREATY ESTONIAN NATIONAL MONITORING NETWORK FOR ENVIRONMENTAL RADIOACTIVITY REPUBLIC OF ESTONIA 19 to 23 September 2005 Reference: EE-05/04 Art. 35 Technical Report – EE-05/04 VERIFICATIONS UNDER THE TERMS OF ARTICLE 35 OF THE EURATOM TREATY FACILITIES Monitoring network for environmental radioactivity in Estonia SITES Tallinn, Harku, Paldiski, Sillamäe, Kunda DATE 19 to 23 September 2005 REFERENCE EE-05/04 INSPECTORS V. Tanner (team leader) P. Vallet Y-H. Bouget (national expert on secondment – France) E. Henrich (national expert on secondment – Austria) DATE OF REPORT 10.3.2006 SIGNATURES V. Tanner P. Vallet E. Henrich Y-H. Bouget Page 2 of 29 Art. 35 Technical Report – EE-05/04 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 6 2. PREPARATION AND CONDUCT OF THE VERIFICATION 7 2.1. PREAMBLE 7 2.2. PREPARATORY DOCUMENTS 7 2.3. PROGRAMME OF THE VISIT 7 2.4. REPRESENTATIVES OF THE ESTONIAN COMPETENT AUTHORITIES AND THE ASSOCIATED LABORATORIES 7 3. BACKGROUND INFORMATION 9 3.1. GENERAL 9 3.2. RESPONSIBLE ORGANISATIONS 9 3.3. PALDISKI SITE 10 3.4. SILLAMÄE SITE 10 4. LEGAL PROVISIONS FOR ENVIRONMENTAL RADIOACTIVITY MONITORING IN ESTONIA 10 5. ENVIRONMENTAL RADIOACTIVITY MONITORING IN ESTONIA 11 5.1. EXTERNAL AMBIENT GAMMA DOSE RATE 11 5.2. AIRBORNE PARTICULATES 12 5.3. SURFACE WATER 12 5.4. DRINKING WATER 13 5.5. MILK PRODUCED IN ESTONIA 13 5.6. FOODSTUFFS - MIXED DIET 13 5.7. PRODUCTS FROM NATURAL ECOSYSTEMS 13 5.8. -

ESTONIA Zemelapis Su Veiklomis Mini

ESTONIA Positively surprising The Charms and Troubles of a Vodka Cellar in Lahemaa The Mystery National park! of the Medieval Monastery Lahemaa Paldiski Tallinn Kayaking? Rakvere Baltic sea ATV RUSSIA Safari! Rapla Medieval Adventures in Haapsalu Rakvere Order Soomaa Tartu Castle! Let’s try Time for a Canoeing? Traditional Bow Loquiz game! Kuressaare Hunting! Saaremaa island Bishops dinner LATVIA Estravel Ltd Suur-Karja 15, 10140 Tallinn Ph. +372 6266233 [email protected] www.baltcoming.com Tallinn Theatrical Sightseeing Tours Theatrical sightseeing tours make a usual trip unique and unforgettable. On these tours the guide provides a historical narrative which musicians and actors bring to life through dramatic performances. Visitors are carried back to medieval times through an engaging mix of authentic entertainment and historical immersion. The Mystery of the Medieval Monastery During the programme the host, dressed in medieval costume, talks about the monastery's history and architecture, monastic life, and lost fortunes, and tells legends of the Dominicans. At the same time the guests can admire the work of local stone masons and listen to the singing of monks. A stop is made at the medie- val "well of wishes" where monastery liqueur is served. The programme ends with a Gregorian chant using the superb acoustics under the vaults of the cloister. Medieval Dinner Visit medieval breweries and taste medieval food in the best Old Town restaurants, or in other historic buildings like an old merchant's house or a monastery. Every place is authentic and has a different image. Friendly staff serves your dinner with a smile and act and talk in the style of medieval times. -

DAY 55 Padise – Paldiski

DAY 55 Padise – Paldiski Paldiski: The Former Closed and Top Secret Town Starting from Padise up to Karilepa, the Baltic Coastal Hiking Route winds through small country roads, while further on to Madise it goes along the side of the road. From the ancient seacoast of the Madise church hill, you will have magnificent views of Paldiski Bay and the Pakri Islands. From Madise to Paldiski, the itinerary continues along the side of the abovementioned road up to the South Harbour and, by going along it, the route reaches the railway station located in the southern part of Paldiski. During Soviet times, Paldiski was a closed town with a military port and a nearby nuclear submarine training base at the Pakri Peninsula that operated using a small nuclear reactor. 4 USEFUL INFORMATION 18 km Roads covered in asphalt and Services are available at the gravel. start and end points. 6–8 h Medium From Madise you can go to the Tallinn – Paldiski railway line Padise centre, (7 km to Põllküla station) and None. then take a train to Paldiski Paldiski railway station, (timetable: https://elron.ee/en/, The Madise – Paldiski section runs ~ 14 times per day). goes along a road with heavy Padise – Madise – Paldiski traffic, so it is recommended to cover the distance by bus (timetables: www.peatus.ee, www.tpilet.ee). I 134 I COASTALHIKING.EU Gulf of Finland 2 POLAND WORTH SEEING! 11 The Peter the Great sea fortress Muula 1 Madise juga. mäed. A fortress cut out of the The 2.2 m high waterfall is high limestone coast with five located in the Harju-Madise bastions. -

Balticconnector – Environmental Impact

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT BALTICCONNECTOR — ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT 2015 REPORT ASSESSMENT IMPACT — ENVIRONMENTAL BALTICCONNECTOR BALTICCONNECTOR Natural gas pipeline between Finland and Estonia 2015 Environmental impact assessment report Estonia ESTONIA BALTICCONNECTOR — ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT CONTACT INFORMATION Project Developers: Gasum Corporation Eero Isoranta Phone: +358 20 447 8652 [email protected] www.gasum.com AS EG Võrguteenus Priit Heinla Phone: +372 617 0028 [email protected] www.egvorguteenus.ee Coordinating authority for the EIA procedure in Estonia: Ministry of Economic Affairs and Communications Taivo Linnamägi Phone: +372 62 56 342 [email protected] Coordinating authority for the EIA procedure in Finland: Uusimaa Centre for Economic Development, Transport and the Environment Leena Eerola Phone: +358 295 021 380 [email protected] EIA consultant: Pöyry Finland Oy Terhi Rauhamäki Phone: +358 10 33 21420 [email protected] Entec Eesti OÜ Andres Piirsalu Phone: +372 50 19662 [email protected] Published by: Gasum Corporation Layout and design: Kreab Base map data: © Maanmittauslaitos, Lupanro 48/MML/14, Estonian Land Board Base Map ETAK (agreement No EP-B2–2713) Cover photo: Ramboll The EIA report and related material are available online at http://www.balticconnector.fi and at http://www.egvorguteenus.ee/kasulikku/balticconnector/ The project’s EIA report for Finland is available in English at http://www.balticconnector.fi 2 BALTICCONNECTOR — ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT FOREWORD Gasum Corporation (hereinafter Gasum) and the Esto- negative impacts caused by alternatives of proposed nian company AS EG Võrguteenus are jointly planning activity in Estonia and Finland. The EIA procedure the Balticconnector natural gas pipeline to intercon- covers the natural gas pipeline route from Ingå, Finland, nect the Finnish and Estonian natural gas distribution to Paldiski, Estonia. -

Estonian Yacht Harbours

Estonian yacht harbours A comparative study by AARE OLL Ministry of Transport and Communications Tallinn 2001 LIST OF CONTENTS Introduction Estonia and its people ..................................................................................... 1 Legislative framework .................................................................................... 2 Navigational safety in Estonian waters ........................................................... 3 Estonian ports by ownership ........................................................................... 4 Estonian ports by activities ............................................................................. 6 Yachting in Estonia ......................................................................................... 7 Estonian and foreign pleasure boats ............................................................... 9 Travel conditions in Western Estonia Archipelago ........................................ 10 Customs regulations ........................................................................................ 11 Official regulations ......................................................................................... 14 Sources of information .................................................................................... 15 Map of Estonian yacht harbours……………………………………………...16 Ports and harbours Dirhami ........................................................................................................... 17 Haapsalu .........................................................................................................