Berlioz: Symphonie Fantastique

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OTHER WORLDS 2019/20 Concert Season at Southbank Centre’S Royal Festival Hall Highlights 2019/20

OTHER WORLDS 2019/20 Concert season at Southbank Centre’s Royal Festival Hall Highlights 2019/20 November Acclaimed soprano Diana Damrau is renowned for her interpretations of the music of Richard Strauss, and this November she sings a selection of her favourite Strauss songs. Page 12 September October Principal Conductor and Mark Elder conducts Artistic Advisor Vladimir Elgar’s oratorio Jurowski is joined by The Apostles, arguably Julia Fischer to launch his greatest creative the second part of Isle achievement, which of Noises with Britten’s will be brought to life elegiac Violin Concerto on this occasion with alongside Tchaikovsky’s a stellar cast of soloists Sixth Symphony. and vast choral forces. Page 03 Page 07 December Legendary British pianist Peter Donohoe plays his compatriot John Foulds’s rarely performed Dynamic Triptych – a unique jazz-filled, exotic masterpiece Page 13 February March January Vladimir Jurowski leads We welcome back violinist After winning rave reviews the first concert in our Anne-Sophie Mutter for at its premiere in 2017, 2020 Vision festival, two exceptional concerts we offer another chance presenting the music in which she performs to experience Sukanya, of three remarkable Beethoven’s groundbreaking Ravi Shankar’s works composed Triple Concerto and extraordinary operatic three centuries apart, a selection of chamber fusion of western and by Beethoven, Scriabin works alongside LPO traditional Indian styles. and Eötvös. Principal musicians. A love story brought to Page 19 Pages 26–27 life through myth, music -

Sally Matthews Is Magnificent

` DVORAK Rusalka, Glyndebourne Festival, Robin Ticciati. DVD Opus Arte Sally Matthews is magnificent. During the Act II court ball her moral and social confusion is palpable. And her sorrowful return to the lake in the last act to be reviled by her water sprite sisters would melt the winter ice. Christopher Cook, BBC Music Magazine, November 2020 Sally Matthews’ Rusalka is sung with a smoky soprano that has surprising heft given its delicacy, and the Prince is Evan LeRoy Johnson, who combines an ardent tenor with good looks. They have great chemistry between them and the whole cast is excellent. Opera Now, November-December 2020 SCHUMANN Paradies und die Peri, Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, Paolo Bortolameolli Matthews is noted for her interpretation of the demanding role of the Peri and also appears on one of its few recordings, with Rattle conducting. The soprano was richly communicative in the taxing vocal lines, which called for frequent leaps and a culminating high C … Her most rewarding moments occurred in Part III, particularly in “Verstossen, verschlossen” (“Expelled again”), as she fervently Sally Matthews vowed to go to the depths of the earth, an operatic tour-de-force. Janelle Gelfand, Cincinnati Business Courier, December 2019 Soprano BARBER Two Scenes from Anthony & Cleopatra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Juanjo Mena This critic had heard a fine performance of this music by Matthews and Mena at the BBC Proms in London in 2018, but their performance here on Thursday was even finer. Looking suitably regal in a glittery gold form-fitting gown, the British soprano put her full, vibrant, richly contoured voice fully at the service of text and music. -

Berlioz's Les Nuits D'été

Berlioz’s Les nuits d’été - A survey of the discography by Ralph Moore The song cycle Les nuits d'été (Summer Nights) Op. 7 consists of settings by Hector Berlioz of six poems written by his friend Théophile Gautier. Strictly speaking, they do not really constitute a cycle, insofar as they are not linked by any narrative but only loosely connected by their disparate treatment of the themes of love and loss. There is, however, a neat symmetry in their arrangement: two cheerful, optimistic songs looking forward to the future, frame four sombre, introspective songs. Completed in 1841, they were originally for a mezzo-soprano or tenor soloist with a piano accompaniment but having orchestrated "Absence" in 1843 for his lover and future wife, Maria Recio, Berlioz then did the same for the other five in 1856, transposing the second and third songs to lower keys. When this version was published, Berlioz specified different voices for the various songs: mezzo-soprano or tenor for "Villanelle", contralto for "Le spectre de la rose", baritone (or, optionally, contralto or mezzo) for "Sur les lagunes", mezzo or tenor for "Absence", tenor for "Au cimetière", and mezzo or tenor for "L'île inconnue". However, after a long period of neglect, in their resurgence in modern times they have generally become the province of a single singer, usually a mezzo-soprano – although both mezzos and sopranos sometimes tinker with the keys to ensure that the tessitura of individual songs sits in the sweet spot of their voices, and transpositions of every song are now available so that it can be sung in any one of three - or, in the case of “Au cimetière”, four - key options; thus, there is no consistency of keys across the board. -

Les Nuits D'été & La Mort De Cléopâtre

HECTOR BERLIOZ Les nuits d'été & La mort de Cléopâtre SCOTTISH CHAMBER ORCHESTRA ROBIN TICCIATI CONDUCTOR KAREN CARGILL MEZZO-SOPRANO HECTOR BERLIOZ Les nuits d’été & La mort de Cléopâtre Scottish Chamber Orchestra Robin Ticciati conductor Karen Cargill mezzo-soprano Recorded at Cover image The Usher Hall, Dragonfly Dance III by Roz Bell Edinburgh, UK 1-4 April 2012 Session photos by John McBride Photography Produced and recorded by Philip Hobbs All scores published by Bärenreiter-Verlag, Kassel Assistant engineer Robert Cammidge Design by gmtoucari.com Post-production by Julia Thomas 2 Les nuits d’été 1. Villanelle ......................................................................................2:18 2. Le spectre de la rose .................................................................6:12 3. Sur les lagunes ............................................................................5:50 4. Absence ......................................................................................4:45 5. Au cimetière ...............................................................................5:32 6. L’île inconnue .............................................................................3:56 Roméo & Juliette 7. Scène d’amour ........................................................................16:48 La mort de Cléopâtre 8. Scène lyrique ..............................................................................9:57 9. Méditation.................................................................................10:08 Total Time: ......................................................................................65:48 -

Symphonien 3, 4 & 9

MAHLER SYMPHONIEN 3, 4 & 9 Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks Bernard Haitink Symphonie Nr. 3 d-Moll / Symphony No. 3 in D minor für Alt-Solo, Knabenchor, Chor und Orchester for alto solo, boys‘ choir, choir and orchestra CD 1 Erste Abteilung 01 I. Kräftig. Entschieden 35:49 CD 2 Zweite Abteilung 01 II. Tempo di Menuetto. Sehr mäßig. Ja nicht eilen! 10:06 02 III. Comodo. Scherzando. Ohne Hast 17:53 03 IV. Sehr langsam. Misterioso. Durchaus ppp („Oh Mensch! Gib Acht!“) 9:34 04 V. Lustig im Tempo und keck im Ausdruck („Es sungen drei Engel“) 4:26 05 VI. Langsam. Ruhevoll. Empfunden 23:40 Total time CD 1 & CD 2: 101:28 Gerhild Romberger Mezzosopran / mezzo soprano Augsburger Domsingknaben / Reinhard Kammler Einstudierung / chorus master Martin Angerer Posthorn-Solo / post horn Chor und Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks Yuval Weinberg Einstudierung / chorus master / Bernard Haitink Dirigent / conductor Live-Aufnahme / live recording: München, Philharmonie im Gasteig, 16./17.06.2016 · Tonmeister/Recording Producer & Schnitt/Editing: Bernhard Albrecht · Toningenieur/Recording Engineer: Peter Urban · Verlag / Publisher: Hrsg. Erwin Ratz und Karl Heinz Füssl © Universal Edition AG, Wien mit freundlicher · Genehmigung von SCHOTT MUSIC, Mainz Gustav Mahler, Toblach 1909 Symphonie Nr. 4 G-Dur Symphonie Nr. 9 D-Dur Symphony No. 4 in G major Symphony No. 9 in D major CD 3 CD 4 01 Bedächtig. Nicht eilen 17:24 01 Andante comodo 26:47 02 In gemächlicher Bewegung. Ohne Hast 9:05 02 Im Tempo eines gemächlichen Ländlers. 03 Ruhevoll 20:40 Etwas täppisch und sehr derb 16:08 04 Sehr behaglich 03 Rondo-Burleske. -

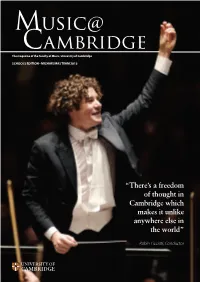

“There's a Freedom of Thought in Cambridge Which Makes It Unlike

The magazine of the Faculty of Music, University of Cambridge SCHOOLS EDITION - MICHAELMAS TERM 2015 “There’s a freedom of thought in Cambridge which makes it unlike anywhere else in the world” Robin Ticciati, Conductor Contents “Music is a moral law. It gives soul to the universe, Primed for success 4 wings to the Alumni share their stories mind, flight to The low-down 10 Applying to Cambridge the imagination , A place to call your own 14 and charm and Choosing a college gaiety to life and Tradition and innovation 16 The Cambridge Music course to everything.” Performance in the Music Faculty 20 Plato The broader context Best of both worlds 21 The CAMRAM scheme explained Calling all composers… 22 Music@Cambridge New music in Cambridge Michaelmas 2015 Composing to connect 23 Music to change the world Published by Faculty of Music 11 West Road, Cambridge CB3 9DP Glittering prizes 24 Music awards at Cambridge A society for all seasons 32 www.mus.cam.ac.uk A year in the life of CUMS [email protected] Joining Forces 33 Britten’s War Requiem remembered @camunimusic Bringing the experts on-side 34 Creative collaboration with the AAM facebook.com/cambridge.universitymusic Different Strokes 35 Learning through lectures Commissioning Editors: Beyond the ivory tower 38 Martin Ennis, Sarah Williams The Cambridge outreach programme Editor: They shoot, he scores 39 E. Jane Dickson Music for film and screen Graphic design: Careers 40 Matt Bilton, Pageworks Life beyond Cambridge Meet the staff 42 Printed by The Lavenham Press Ltd Arbons House 47 Water Street Lavenham Suffolk CO10 9RN on the cover Robin Ticciati ©Marco Borggreve Welcome usty folios, fusty But what’s so special about studying Music at dons. -

Roméo Et Juliette

HECTOR BERLIOZ Roméo et Juliette ROBIN TICCIATI CONDUCTOR SWEDISH RADIO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA & SWEDISH RADIO CHOIR HECTOR BERLIOZ (1803–1869) Roméo et Juliette DRAMATIC SYMPHONY FOR SOLOISTS, CHORUS AND ORCHESTRA, OP. 17 Robin Ticciati conductor Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra Swedish Radio Choir Katija Dragojevic mezzo-soprano Andrew Staples tenor Alastair Miles bass Recorded live at concerts in the Berwaldhallen, Stockholm, Sweden, 3–8 November 2014 Produced by Philip Hobbs Recorded by Philip Hobbs and Johan Hyttnäs Post-production by Julia Thomas Cover image by Karen Taddeo Design by gmtoucari.com Edition by D. Kern Holoman (Bärenreiter, 1990) 1 Disc 1 No. 1 1. Introduction instrumentale : Combats – Tumulte – Intervention du Prince ....................................... 4:43 2. Prologue : Récitatif harmonique : « D’anciennes haines endormies » ............... 5:11 3. Strophes : « Premiers transports que nul n’oublie! » ............................ 6:01 4. « Bientôt de Roméo » – Scherzetto vocal : « Mab, la messagère » ... 3:20 No. 2 : Andante et Allegro 5. Roméo seul. Tristesse – Bruit lontain de bal et de concert ................. 6:57 6. Grande fête chez Capulet .................................................................... 5:55 No. 3 : Scène d’amour 7. Nuit sereine. Le jardin de Capulet, silencieux et désert ................... 18:53 Disc 2 No. 4 : Scherzo 1. La reine Mab, ou la Fée des songes ..................................................... 8:10 No. 5 : Convoi funèbre de Juliette 2. « Jetez des fleurs pour la vierge expirée! » ........................................... 9:29 No. 6 : Roméo au tombeau des Capulets 3. Roméo au tombeau des Capulets ...................................................... 1:33 4. Invocation – Réveil de Juliette – Joie délirante, désespoir, dernières angoisses et mort des deux amants .................................... 6:18 No. 7 : Final 5. La foule accourt au cimetière – Rixe des Capulets et des Montagus .................................................................................... -

The Young Conductor Looks to the Future

THE WORLD’S BEST CLASSICAL MUSIC REVIEWS Est 1923 . APRIL 2018 gramophone.co.uk Robin Ticciati The young conductor looks to the future PLUS Paul Lewis explores Haydn’s piano sonatas Handel’s Saul: the finest recordings UNITED KINGDOM £5.75 Intimate concerts featuring internationally acclaimed classical musicians in central London Now Booking Until July 2018 Igor Levit Cuarteto Casals: Beethoven Cycle Roderick Williams: Exploring Schubert’s Song Cycles O/Modernt: Purcell from the Ground Up Haydn String Quartet Series Jörg Widmann as Composer-Performer and much more… The Wigmore Hall Trust 36 Wigmore Street, London W1U 2BP Director: John Gilhooly OBE www.wigmore-hall.org.uk Registered Charity Number 1024838 A special eight-page section focusing on recent recordings from the US and Canada JS Bach Solo Violin Sonatas and Partitas, BWV1001-1006 talks to ... Johnny Gandelsman vn In a Circle F b ICR101 (124’ • DDD) Johnny Gandelsman The violinist and co-founder Bach’s Violin of Brooklyn Rider discusses his Sonatas and debut solo recording of Bach Partitas are among the most frequently Was it a challenge to plunge straight into performed works for the instrument, Bach for your first solo recording? or any instrument. Recordings evince a Not really. Over the the last three years spectrum of approaches, from historical I’ve performed all six Sonatas and Partitas treatments on period instruments to in concert about 30 times, which has been concepts Romantic and beyond. deeply rewarding. I wanted to capture this Among the newest journeys is Johnny moment of personal learning and growth. Gandelsman’s freshly considered account Do you miss the collaborative process of these monuments. -

L'enfance Du Christ

HECTOR BERLIOZ L’enfance du Christ ROBIN TICCIATI CONDUCTOR SWEDISH RADIO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA & CHOIR HECTOR BERLIOZ L’enfance du Christ Robin Ticciati conductor Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra & Choir Yann Beuron Le Récitant Véronique Gens Marie Stephan Loges Joseph Alastair Miles Le Père de la Famille Recorded at Post-production by Berwaldhallen, Östermalm, Julia Thomas Stockholm, Sweden from 11 – 14 December 2012 Sleeve image by Per Kirkeby Produced and engineered for Linn by Philip Hobbs Cover image Flugten til Ægypten Produced for Swedish Radio by by Per Kirkeby, 1996. Cynthia Zetterqvist Oil on canvas. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, Engineered for Swedish Radio by New York and London Johan Hyttnäs Design by gmtoucari.com Partie I, Le songe d’Hérode 1. Prologue 1:49 2. Scène I : Marche nocturne 8:14 3. Scène II : Air d’Hérode : Toujours ce rêve ! 1:08 4. Scène II : Air d’Hérode : O misère des rois ! 6:13 5. Scène III : Seigneur ! 0:41 6. Scène IV : Les sages de Judée 8:56 7. Scène V : Duo : O mon cher fils 7:42 8. Scène VI : Joseph ! Marie ! 4:27 Partie II, La fuite en Égypte 9. Ouverature 5:40 10. L’adieu des bergers : Il s’en va loin de la terre 4:02 11. Le repos de la Sainte Famille : 6:00 Les pèlerains étant venus Partie III, L’arrivée à Saïs 12. Depuis trois jours, malgré l’ardeur du vent 3:30 13. Scène I : Duo : Dans cette ville immense 4:56 14. Scène II : Entrez, entrez, pauvres Hébreux ! 6:57 15. Scène II : Trio pour deux flûtes et harpe 6:43 16. -

London's Symphony Orchestra

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Thursday 19 September 2013 7.30pm Barbican Hall UCHIDA’S MOZART Mozart Rondo for Solo Piano London’s Symphony Orchestra Mozart Piano Concerto No 17 INTERVAL Matthew Kaner The Calligrapher’s Manuscript an LSO Panufnik Young Composers Scheme commission, supported by the Helen Hamlyn Trust Dvorˇák Symphony No 5 Robin Ticciati conductor Mitsuko Uchida piano Concert ends approx 9.45pm 2 Welcome 19 September 2013 Welcome Living Music to tonight’s concert In Brief Following the launch of the LSO 2013/14 concert THE LSO AT THE BBC PROMS season last Sunday, It is a pleasure to welcome tonight’s soloist Mitusko Uchida, a long-standing The Orchestra appeared twice at the BBC Proms friend of the LSO, who opens this evening’s this summer attracting fantastic reviews. The first performance with a personal tribute to Sir Colin concert, conducted by Principal Conductor Valery Davis – the Mozart Rondo in A minor for solo piano. Gergiev, featured music by Borodin, Glazunov, Mussorgsky and the UK premiere of Sofia Mitsuko Uchida and Sir Colin were close musical allies Gubaidulina’s The Rider on the White Horse. for many years, sharing a passion for Mozart’s work The second was an all-British programme led by which they have performed together on several Principal Guest Conductor Daniel Harding. occasions with the LSO. Following this solo performance, we welcome tonight’s conductor, lso.co.uk/concertreviews Robin Ticciati, and the Orchestra to the platform. Since Ticciati’s debut with the LSO in 2010, he has appeared with the Orchestra many times and is THE Latest RELEASE FROM LSO LIVE another musician with whom Sir Colin had a close relationship. -

The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Historical Performance in Music Edited by Colin Lawson , Robin Stowell Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-10808-0 — The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Historical Performance in Music Edited by Colin Lawson , Robin Stowell Frontmatter More Information The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Historical Performance in Music Recent decades have seen a major increase of interest in historical performance practice, but until now there has been no comprehensive reference tool avail- able on the subject. This fully up-to-date, illuminating and accessible volume will assist readers in rediscovering and recreating as closely as possible how musical works may originally have sounded. Focusing on performance, this Encyclopedia contains entries in categories including issues of style, techniques and practices, the history and development of musical instruments, and the work of performers, scholars, theorists, composers and editors. It features contributions from more than 100 leading experts who provide a geographic- ally varied survey of both theory and practice, as well as evaluation of and opinions on the resolution of problems in period performance. This timely and groundbreaking book will be an essential resource for students, scholars, teachers, performers and audiences. colin lawson is Director of the Royal College of Music in London. He is a world-renowned period clarinettist and has played principal in most of Brit- ain’s leading period orchestras, with which he has recorded and toured world- wide. He has published extensively and is co-editor, with Robin Stowell, of a series of Cambridge Handbooks to the Historical Performance of Music as well as of The Cambridge History of Musical Performance (Cambridge, 2012). robin stowell is Emeritus Professor of Music at Cardiff University. -

Magdalena Kožená Chamber Orchestra of Europe Robin Ticciati

Kölner Sonntagskonzerte 4 Magdalena Kožená Chamber Orchestra of Europe Robin Ticciati Sonntag 27. Januar 2019 18:00 Bitte beachten Sie: Ihr Husten stört Besucher und Künstler. Wir halten daher für Sie an den Garderoben Ricola-Kräuterbonbons bereit. Sollten Sie elektronische Geräte, insbesondere Mobiltelefone, bei sich haben: Bitte schalten Sie diese unbedingt zur Vermeidung akustischer Störungen aus. Wir bitten um Ihr Verständnis, dass Bild- und Tonaufnahmen aus urheberrechtlichen Gründen nicht gestattet sind. Wenn Sie einmal zu spät zum Konzert kommen sollten, bitten wir Sie um Verständnis, dass wir Sie nicht sofort einlassen können. Wir bemühen uns, Ihnen so schnell wie möglich Zugang zum Konzertsaal zu gewähren. Ihre Plätze können Sie spätestens in der Pause einnehmen. Bitte warten Sie den Schlussapplaus ab, bevor Sie den Konzertsaal verlassen. Es ist eine schöne und respektvolle Geste gegenüber den Künstlern und den anderen Gästen. Mit dem Kauf der Eintrittskarte erklären Sie sich damit einverstanden, dass Ihr Bild möglicherweise im Fernsehen oder in anderen Medien ausgestrahlt oder veröffentlicht wird. Vordruck/Lackform_2017.indd 2-3 14.07.17 12:44 Kölner Sonntagskonzerte 4 Magdalena Kožená Mezzosopran Chamber Orchestra of Europe Robin Ticciati Dirigent Sonntag 27. Januar 2019 18:00 Pause gegen 18:50 Ende gegen 19:50 17:00 Einführung in das Konzert durch Oliver Binder PROGRAMM Gabriel Fauré 1845 – 1924 Pelléas et Mélisande op. 80 (1898) Suite für Orchester Prélude. Quasi Adagio La Fileuse. Andantino quasi Allegretto Sicilienne. Allegretto molto moderato La Mort de Mélisande. Molto Adagio Hector Berlioz 1803 – 1869 Les Nuits d’été op. 7 (1840 – 41) Sechs Lieder für Singstimme und Orchester Villanelle Le spectre de la rose Sur les lagunes Absence Au cimetière (clair de lune) L’ île inconnue Pause Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 1756 – 1791 Sinfonie C-Dur KV 425 (1783) (»Linzer Sinfonie«) Adagio – Allegro spiritoso Andante Menuetto – Trio Presto 2 DIE GESANGSTEXTE Hector Berlioz Les Nuits d’été op.