Berlioz's Les Nuits D'été

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mozart Magic Philharmoniker

THE T A R S Mass, in C minor, K 427 (Grosse Messe) Barbara Hendricks, Janet Perry, sopranos; Peter Schreier, tenor; Benjamin Luxon, bass; David Bell, organ; Wiener Singverein; Herbert von Karajan, conductor; Berliner Mozart magic Philharmoniker. Mass, in C major, K 317 (Kronungsmesse) (Coronation) Edith Mathis, soprano; Norma Procter, contralto...[et al.]; Rafael Kubelik, Bernhard Klee, conductors; Symphonie-Orchester des on CD Bayerischen Rundfunks. Vocal: Opera Così fan tutte. Complete Montserrat Caballé, Ileana Cotrubas, so- DALENA LE ROUX pranos; Janet Baker, mezzo-soprano; Nicolai Librarian, Central Reference Vocal: Vespers Vesparae solennes de confessore, K 339 Gedda, tenor; Wladimiro Ganzarolli, baritone; Kiri te Kanawa, soprano; Elizabeth Bainbridge, Richard van Allan, bass; Sir Colin Davis, con- or a composer whose life was as contralto; Ryland Davies, tenor; Gwynne ductor; Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal pathetically brief as Mozart’s, it is Howell, bass; Sir Colin Davis, conductor; Opera House, Covent Garden. astonishing what a colossal legacy F London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. Idomeneo, K 366. Complete of musical art he has produced in a fever Anthony Rolfe Johnson, tenor; Anne of unremitting work. So much music was Sofie von Otter, contralto; Sylvia McNair, crowded into his young life that, dead at just Vocal: Masses/requiem Requiem mass, K 626 soprano...[et al.]; Monteverdi Choir; John less than thirty-six, he has bequeathed an Barbara Bonney, soprano; Anne Sofie von Eliot Gardiner, conductor; English Baroque eternal legacy, the full wealth of which the Otter, contralto; Hans Peter Blochwitz, tenor; soloists. world has yet to assess. Willard White, bass; Monteverdi Choir; John Le nozze di Figaro (The marriage of Figaro). -

ARSC Journal, Spring 1992 69 Sound Recording Reviews

SOUND RECORDING REVIEWS Chicago Symphony Orchestra: The First Hundred Years CS090/12 (12 CDs: monaural, stereo; ADD)1 Available only from the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, 220 S. Michigan Ave, Chicago, IL, for $175 plus $5 shipping and handling. The Centennial Collection-Chicago Symphony Orchestra RCA-Victor Gold Seal, GD 600206 (3 CDs; monaural, stereo, ADD and DDD). (total time 3:36:3l2). A "musical trivia" question: "Which American symphony orchestra was the first to record under its own name and conductor?" You will find the answer at the beginning of the 12-CD collection, The Chicago Symphony Orchestra: The First 100 Years, issued by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO). The date was May 1, 1916, and the conductor was Frederick Stock. 3 This is part of the orchestra's celebration of the hundredth anniversary of its founding by Theodore Thomas in 1891. Thomas is represented here, not as a conductor (he died in 1904) but as the arranger of Wagner's Triiume. But all of the other conductors and music directors are represented, as well as many guests. With one exception, the 3-CD set, The Centennial Collection: Chicago Symphony Orchestra, from RCA-Victor is drawn from the recordings that the Chicago Symphony made for that company. All were released previously, in various formats-mono and stereo, 78 rpm, 45 rpm, LPs, tapes, and CDs-as the technologies evolved. Although the present digital processing varies according to source, the sound is generally clear; the Reiner material is comparable to RCA-Victor's on-going reissues on CD of the legendary recordings produced by Richard Mohr. -

Aoife Miskelly Soprano

Aoife Miskelly Soprano Northern Irish soprano Aoife Miskelly Codetta in their performance – live on studied as a Sickle Foundation Scholar on the Spanish radio – of Beethoven’s oratorio Christ Opera Masters degree course at the Royal on the Mount of Olives in Cuenca. Aoife is also Academy of Music in London, graduating in a very keen oratorio singer, having performed 2012 with the Regency Award. During her in a whole host of concerts, including Bach’s studies, Aoife was a Kathleen Ferrier Awards Christmas Oratorio, St. John and Matthew finalist (2010), won a BBC Northern Ireland Passions, Jauchzet Gott in allen Landen and Young Artists Platform Award, and was a Magnificat, Beethoven’s Mass in C (in Samling Scholar, Internationale Cologne Cathedral), Brahms’ Deutches Meistersinger Akademie Young Artist and Requiem (St. Martin in the Fields), Carissimi’s Britten-Pears Young Artist. Aoife was the Jepthe (St. John’s, Smith Square), Handel’s winner of the Hampshire National Singing Messiah, Dixit Dominus, Laudate Pueri Competition in 2011, the Bernadette Greevy Dominum, and Saul (conducted by Laurence Bursary in 2011, finalist in the Veronica Dunne Cummings), Mozart’s Requiem, Coronation International Singing Competition 2013, and Mass and Exultate Jubilate, Orff’s Carmina finalist in the 2015 Wigmore Hall Song Burana (Ulster Orchestra), Poulenc’s Gloria, Competition. Stravinsky’s Mass, Varese’s Nocturnal and Vivaldi’s Gloria. During the 2012-16 seasons Aoife was a soloist at the Cologne Opera House where she Aoife’s recent highlights include -

13Th February 2021 Dear All Tomorrow Is One of Those Strangely

13th February 2021 Dear all Tomorrow is one of those strangely named Sundays – the Sunday Next Before Lent. I’m not quite sure why the ‘next’ comes in , but it interesting that both of the penitential seasons in the church calendar have a countdown… 3rd Sunday before Advent, 2nd Sunday before Lent etc.. We often see Advent and Lent as periods leading up to the exciting seasons of Christmas and Easter, but the church calendar requires us to take them seriously in their own right. What will we be doing for Lent? Let’s gear ourselves up… get ready… set… and, go! In a recent letter I suggested a few books or courses you might be interested in. I also invited anyone to request an ash cross stone, to be left on their doorstep. Please let me know by Wednesday, so that I know how many to prepare. Tomorrow’s service details: Readings – 2 Kings 2: 1-12; 2 Corinthians 4: 3-6; Psalm 50: 1-6; Mark 9: 2-9 Hymns: Jesus on the mountain peak; ‘Tis good, Lord, to be here. Lent Course: Next Thursday is the day after Ash Wednesday, and so we will put our study of Mark’s gospel on hold, and instead follow our Lent Course. The details are the same as always: We will meet on Zoom, Thursdays 2.30-3.30ish pm. The Zoom details are: https://us04web.zoom.us/j/8109399155?pwd=STVVTU44RzJxTFFHbTY1MnI0bjJ2Zz09 Meeting ID: 810 939 9155 Passcode: 1w2C9a Please note that, on Thursday 25th February the Lent Course will take place in the morning , at 10.30am. -

A Midsummer Night's Dream

Monday 25, Wednesday 27 February, Friday 1, Monday 4 March, 7pm Silk Street Theatre A Midsummer Night’s Dream by Benjamin Britten Dominic Wheeler conductor Martin Lloyd-Evans director Ruari Murchison designer Mark Jonathan lighting designer Guildhall School of Music & Drama Guildhall School Movement Founded in 1880 by the Opera Course and Dance City of London Corporation Victoria Newlyn Head of Opera Caitlin Fretwell Chairman of the Board of Governors Studies Walsh Vivienne Littlechild Dominic Wheeler Combat Principal Resident Producer Jonathan Leverett Lynne Williams Martin Lloyd-Evans Language Coaches Vice-Principal and Director of Music Coaches Emma Abbate Jonathan Vaughan Lionel Friend Florence Daguerre Alex Ingram de Hureaux Anthony Legge Matteo Dalle Fratte Please visit our website at gsmd.ac.uk (guest) Aurelia Jonvaux Michael Lloyd Johanna Mayr Elizabeth Marcus Norbert Meyn Linnhe Robertson Emanuele Moris Peter Robinson Lada Valešova Stephen Rose Elizabeth Rowe Opera Department Susanna Stranders Manager Jonathan Papp (guest) Steven Gietzen Drama Guildhall School Martin Lloyd-Evans Vocal Studies Victoria Newlyn Department Simon Cole Head of Vocal Studies Armin Zanner Deputy Head of The Guildhall School Vocal Studies is part of Culture Mile: culturemile.london Samantha Malk The Guildhall School is provided by the City of London Corporation as part of its contribution to the cultural life of London and the nation A Midsummer Night’s Dream Music by Benjamin Britten Libretto adapted from Shakespeare by Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears -

AUTUNNO in MUSICA Festival De Musique Classique

AUTUNNO IN MUSICA Festival de musique classique 16-30 OCTOBRE 2014 Le festival Autunno in Musica fête, en 2014, sa quatrième année d’existence en prolongeant ses ambitions patrimoniales, qui font que le passé revit grâce au présent et qu’il rend le présent plus vivant. Il met, comme toujours, l’accent sur le lieu dans lequel les concerts s’inscrivent, car c’est en partie à la mémoire des compositeurs qui vécurent dans les murs de la Villa Médicis qu’il se consacre, tout en s’ouvrant à une vision renouvelée de la musique écrite entre le XVIIIe siècle et le début du XXe, entre la France et l’Italie. Cette année voisineront certaines « vedettes » du Prix de Rome, comme Claude Debussy et André Caplet, d’autres en pleine réhabilitation comme Théodore Dubois, d’autres enfin dont un vrai travail de redécouverte permet d’apprécier la qualité, comme Gaston Salvayre. Mais Autunno in Musica n’oublie pas non plus certains « refusés » du concours, qu’ils soient « non-récompensés » comme Benjamin Godard et Ernest Chausson, ou seulement second Prix de Rome comme Nadia Boulanger et – ce fut le grand scandale de 1905 – Maurice Ravel. Autunno in Musica fait aussi cette année la part belle aux femmes compositrices, telles Marie Jaëll, Henriette Renié ou encore Cécile Chaminade. Pour défendre cette musique, il fallait que soient rassemblés les meilleurs interprètes actuels, avec un intérêt particulier porté à la jeune génération, capable de lectures audacieuses et inattendues : c’est le cas du jeune harpiste soliste de l’Opéra de Paris, Emmanuel Ceysson, du Trio Arcadis (2e prix du Concours international de musique de chambre de Lyon), de la mezzo-soprano Isabelle Druet (lauréate du Concours Reine Elizabeth et plus récemment du parcours Rising Star), ainsi que du Quatuor Giardini et du pianiste David Bismuth. -

ORCHESTRE DE LA SUISSE ROMANDE Director Titular: JONATHAN NOTT

A.7 ORCHESTRE DE LA SUISSE ROMANDE Director Titular: JONATHAN NOTT SERIE ARRIAGA 2016.2017 Auditorio Nacional Medio colaborador de Música A.7 ORCHESTRE DE LA SUISSE ROMANDE Fue fundada, en 1918, por Ernest Ansermet, que fue su Director hasta 1967. Está formada por 112 músicos permanentes. Sus actividades incluyen una serie de conciertos de abono, en Ginebra y Lausana, los conciertos sinfónicos oficiales de la ciudad de Ginebra, el Concierto Benéfico Anual de las Naciones Unidas y representaciones de ópera en el Grand Théâtre de Ginebra. Jonathan Nott ocupa el puesto de Director Titular, a partir de la temporada 2016-2017. Su Principal Director Invitado es el japonés Kazuki Yamada. Desde sus inicios y bajo el liderazgo de su fundador y de sus sucesores Paul Kletzki (1967-1970), Wolfgang Sawallisch (1970-1980), Horst Stein (1980-1985), Armin Jordan (1985-1997), Fabio Luisi (1997-2002), Pinchas Steinberg (2002- 2005), Marek Janowski (2005-2012) y Neeme Järvi (2012-2015), la orquesta ha contribuido activamente a la historia de la música a través del apoyo a compositores contemporáneos. Una de sus misiones más importantes es el apoyo a nueva música orquestal, especialmente de compositores suizos. Desde sus comienzos y en colaboración con la Televisión Suiza-Francesa sus conciertos llegan a un público de millones de personas en todo el mundo. Gracias a su estrecho trabajo con Decca, se realizaron legendarias grabaciones. El resto de los registros, para unos doce sellos diferentes, han recibido numerosos premios. Más recientemente, la orquesta ha desarrollado una privilegiada colaboración con PentaTone. Sus giras internacionales la han llevado a actuar en las principales salas de concierto de Europa (Berlín, Londres, Viena, Salzburgo, París, Madrid, Barcelona, Budapest y Ámsterdam), Asia (Tokio, Seúl, Beijing), así como en América (Boston, Nueva York, San Francisco, Washington, São Paulo, Buenos Aires y Montevideo). -

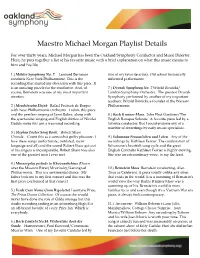

Michael Morgan Playlist

Maestro Michael Morgan Playlist Details For over thirty years, Michael Morgan has been the Oakland Symphony Conductor and Music Director. Here, he puts together a list of his favorite music with a brief explanation on what this music means to him and his life. 1.) Mahler Symphony No. 7. Leonard Bernstein two of my favorite artists. Old school historically conducts New York Philharmonic. This is the informed performance. recording that started my obsession with this piece. It is an amazing puzzle for the conductor. And, of 7.) Dvorak Symphony No. 7 Witold Rowicki/ course, Bernstein was one of my most important London Symphony Orchestra. The greatest Dvorak mentors. Symphony performed by another of my important teachers: Witold Rowicki, a founder of the Warsaw 2.) Mendelssohn Elijah. Rafael Frubeck de Burgos Philharmonic. with New Philharmonia Orchestra. I adore this piece and the peerless singing of Janet Baker, along with 8.) Bach B minor Mass. John Eliot Gardiner/The the spectacular singing and English diction of Nicolai English Baroque Soloists. A favorite piece led by a Gedda make this just a treasured recording. favorite conductor. But I could endorse any of a number of recordings by early music specialists. 3.) Stephen Foster Song Book. Robert Shaw Chorale. Count this as a somewhat guilty pleasure. I 9.) Schumann Frauenlieben und Leben. Any of the love these songs (unfortunate, outdated, racist recordings by Kathleen Ferrier. The combination of language and all) and the sound Robert Shaw got out Schumann's heartfelt song cycle and the great of his singers is incomparable. Robert Shaw was also English Contralto Kathleen Ferrier is highly moving. -

Liturgical Drama in Bach's St. Matthew Passion

Uri Golomb Liturgical drama in Bach’s St. Matthew Passion Bach’s two surviving Passions are often cited as evidence that he was perfectly capable of producing operatic masterpieces, had he chosen to devote his creative powers to this genre. This view clashes with the notion that church music ought to be calm and measured; indeed, Bach’s contract as Cantor of St. Thomas’s School in Leipzig stipulated: In order to preserve the good order in the churches, [he would] so arrange the music that it shall not last too long, and shall be of such nature as not to make an operatic impression, but rather incite the listeners to devotion. (New Bach Reader, p. 105) One could argue, however, that Bach was never entirely faithful to this pledge, and that in the St. Matthew Passion he came close to violating it entirely. This article explores the fusion of the liturgical and the dramatic in the St. Matthew Passion, viewing the work as the combination of two dramas: the story of Christ’s final hours, and the Christian believer’s response to this story. This is not, of course, the only viable approach to this masterpiece. The St. Matthew Passion is a complex, heterogeneous work, rich in musical and expressive detail yet also displaying an impressive unity across its vast dimensions. This article does not pretend to explore all the work’s aspects; it only provides an overview of one of its distinctive features. 1. The St. Matthew Passion and the Passion genre The Passion is a musical setting of the story of Christ’s arrest, trial and crucifixion, intended as an elaboration of the Gospel reading in the Easter liturgy. -

Debussy's Pelléas Et Mélisande

Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande - A discographical survey by Ralph Moore Pelléas et Mélisande is a strange, haunting work, typical of the Symbolist movement in that it hints at truths, desires and aspirations just out of reach, yet allied to a longing for transcendence is a tragic, self-destructive element whereby everybody suffers and comes to grief or, as in the case of the lovers, even dies - yet frequent references to fate and Arkel’s ascribing that doleful outcome to ineluctable destiny, rather than human weakness or failing, suggest that they are drawn, powerless, to destruction like moths to the flame. The central enigma of Mélisande’s origin and identity is never revealed; that riddle is reflected in the wispy, amorphous property of the music itself, just as the text, adapted from Maeterlinck’s play, is vague and allusive, rarely open or direct in its expression of the characters’ velleities. The opera was highly innovative and controversial, a gateway to a new style of modern music which discarded and re-invented operatic conventions in a manner which is still arresting and, for some, still unapproachable. It is a work full of light and shade, sunlit clearings in gloomy forest, foetid dungeons and sea-breezes skimming the battlements, sparkling fountains, sunsets and brooding storms - all vividly depicted in the score. Any francophone Francophile will delight in the nuances of the parlando text. There is no ensemble or choral element beyond the brief sailors’ “Hoé! Hisse hoé!” offstage and only once do voices briefly intertwine, at the climax of the lovers' final duet. -

Frederic Albou, Bass-Baritone

Frederic Albou, bass-baritone 0033 1 46 63 88 19 0033 6 80 12 63 99 http://www.fredericalbou.com/ [email protected] After graduating in literature, musicology and conducting, and receiving an award from the CNR of Reims in clarinet, Frédéric Albou started to study singing with Christiane Patard, and worked with such coaches as Janine Reiss, Marie-Jeanne Serero, Olivier Reboul, Erika Guiormar, Jory Vinikour and Brigitte Clair. He also improved his mastery under the advices of Jorge Chamine, Teresa Berganza, Ruggero Raimondi, Alain Fondary, Sergei Leiferkus, Eva Märtson, Anna Ringart, Russel Smythe and Howard Crook. He has been trained as an actor by Ruth Ortmann, Roberto Maria Grassi and Catherine Riboli, and practises Chinese martial arts with Master Tien Shue. His is a passionate and committed path dedicated to a wide repertoire. Thus since 1999 he is a member of the Ensemble Kerylos, devoted to Ancient Greek musical scores, founded and conducted by Annie Bélis, with whom he has premiered several works (Medea by Karkinos, Hymn to Lemnos, by Euripides, Abstract from Theseus by Sophokles, Nequia from the Oslo Papyrus, Hymn to Apollo from the Yale Papyrus), and has performed in such renowned venues as the Grand Amphitheatre de la Sorbonne, the Auditorium du Louvre, or Lyon’s Archaeological Museum. Together with that band he also recorded several radio and television broadcasted programmes, and is to prepare a new double CD. He has also performed Renaissance polyphonic music, particularly with the Huelgas Ensemble, conducted by Paul Van Nevel, with whom he sang in various European festivals (Saintes, Noirlac, Tongeren), and recorded the CD Sommets de la polyphonie flamande (Harmonia Mundi). -

Navigating, Coping & Cashing In

The RECORDING Navigating, Coping & Cashing In Maze November 2013 Introduction Trying to get a handle on where the recording business is headed is a little like trying to nail Jell-O to the wall. No matter what side of the business you may be on— producing, selling, distributing, even buying recordings— there is no longer a “standard operating procedure.” Hence the title of this Special Report, designed as a guide to the abundance of recording and distribution options that seem to be cropping up almost daily thanks to technology’s relentless march forward. And as each new delivery CONTENTS option takes hold—CD, download, streaming, app, flash drive, you name it—it exponentionally accelerates the next. 2 Introduction At the other end of the spectrum sits the artist, overwhelmed with choices: 4 The Distribution Maze: anybody can (and does) make a recording these days, but if an artist is not signed Bring a Compass: Part I with a record label, or doesn’t have the resources to make a vanity recording, is there still a way? As Phil Sommerich points out in his excellent overview of “The 8 The Distribution Maze: Distribution Maze,” Part I and Part II, yes, there is a way, or rather, ways. But which Bring a Compass: Part II one is the right one? Sommerich lets us in on a few of the major players, explains 11 Five Minutes, Five Questions how they each work, and the advantages and disadvantages of each. with Three Top Label Execs In “The Musical America Recording Surveys,” we confirmed that our readers are both consumers and makers of recordings.