The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Historical Performance in Music Edited by Colin Lawson , Robin Stowell Frontmatter More Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OTHER WORLDS 2019/20 Concert Season at Southbank Centre’S Royal Festival Hall Highlights 2019/20

OTHER WORLDS 2019/20 Concert season at Southbank Centre’s Royal Festival Hall Highlights 2019/20 November Acclaimed soprano Diana Damrau is renowned for her interpretations of the music of Richard Strauss, and this November she sings a selection of her favourite Strauss songs. Page 12 September October Principal Conductor and Mark Elder conducts Artistic Advisor Vladimir Elgar’s oratorio Jurowski is joined by The Apostles, arguably Julia Fischer to launch his greatest creative the second part of Isle achievement, which of Noises with Britten’s will be brought to life elegiac Violin Concerto on this occasion with alongside Tchaikovsky’s a stellar cast of soloists Sixth Symphony. and vast choral forces. Page 03 Page 07 December Legendary British pianist Peter Donohoe plays his compatriot John Foulds’s rarely performed Dynamic Triptych – a unique jazz-filled, exotic masterpiece Page 13 February March January Vladimir Jurowski leads We welcome back violinist After winning rave reviews the first concert in our Anne-Sophie Mutter for at its premiere in 2017, 2020 Vision festival, two exceptional concerts we offer another chance presenting the music in which she performs to experience Sukanya, of three remarkable Beethoven’s groundbreaking Ravi Shankar’s works composed Triple Concerto and extraordinary operatic three centuries apart, a selection of chamber fusion of western and by Beethoven, Scriabin works alongside LPO traditional Indian styles. and Eötvös. Principal musicians. A love story brought to Page 19 Pages 26–27 life through myth, music -

Sally Matthews Is Magnificent

` DVORAK Rusalka, Glyndebourne Festival, Robin Ticciati. DVD Opus Arte Sally Matthews is magnificent. During the Act II court ball her moral and social confusion is palpable. And her sorrowful return to the lake in the last act to be reviled by her water sprite sisters would melt the winter ice. Christopher Cook, BBC Music Magazine, November 2020 Sally Matthews’ Rusalka is sung with a smoky soprano that has surprising heft given its delicacy, and the Prince is Evan LeRoy Johnson, who combines an ardent tenor with good looks. They have great chemistry between them and the whole cast is excellent. Opera Now, November-December 2020 SCHUMANN Paradies und die Peri, Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, Paolo Bortolameolli Matthews is noted for her interpretation of the demanding role of the Peri and also appears on one of its few recordings, with Rattle conducting. The soprano was richly communicative in the taxing vocal lines, which called for frequent leaps and a culminating high C … Her most rewarding moments occurred in Part III, particularly in “Verstossen, verschlossen” (“Expelled again”), as she fervently Sally Matthews vowed to go to the depths of the earth, an operatic tour-de-force. Janelle Gelfand, Cincinnati Business Courier, December 2019 Soprano BARBER Two Scenes from Anthony & Cleopatra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Juanjo Mena This critic had heard a fine performance of this music by Matthews and Mena at the BBC Proms in London in 2018, but their performance here on Thursday was even finer. Looking suitably regal in a glittery gold form-fitting gown, the British soprano put her full, vibrant, richly contoured voice fully at the service of text and music. -

Berlioz's Les Nuits D'été

Berlioz’s Les nuits d’été - A survey of the discography by Ralph Moore The song cycle Les nuits d'été (Summer Nights) Op. 7 consists of settings by Hector Berlioz of six poems written by his friend Théophile Gautier. Strictly speaking, they do not really constitute a cycle, insofar as they are not linked by any narrative but only loosely connected by their disparate treatment of the themes of love and loss. There is, however, a neat symmetry in their arrangement: two cheerful, optimistic songs looking forward to the future, frame four sombre, introspective songs. Completed in 1841, they were originally for a mezzo-soprano or tenor soloist with a piano accompaniment but having orchestrated "Absence" in 1843 for his lover and future wife, Maria Recio, Berlioz then did the same for the other five in 1856, transposing the second and third songs to lower keys. When this version was published, Berlioz specified different voices for the various songs: mezzo-soprano or tenor for "Villanelle", contralto for "Le spectre de la rose", baritone (or, optionally, contralto or mezzo) for "Sur les lagunes", mezzo or tenor for "Absence", tenor for "Au cimetière", and mezzo or tenor for "L'île inconnue". However, after a long period of neglect, in their resurgence in modern times they have generally become the province of a single singer, usually a mezzo-soprano – although both mezzos and sopranos sometimes tinker with the keys to ensure that the tessitura of individual songs sits in the sweet spot of their voices, and transpositions of every song are now available so that it can be sung in any one of three - or, in the case of “Au cimetière”, four - key options; thus, there is no consistency of keys across the board. -

Berlioz: Symphonie Fantastique

SCOTTISH CHAMBER ORCHESTRA ROBIN TICCIATI HECTOR BERLIOZ Symphonie Fantastique HECTOR BERLIOZ (180 3–1869) Symphonie Fantastique Symphonie Fantastique, Op. 14 1 Rêveries – Passions 15.12 2 Un bal 6.20 3 Scène aux champs 16.17 4 Marche au supplice 6.35 5 Songe d’une nuit de sabbat 10.21 Béatrice et Bénédict 6 Overture 8.14 TOTAL TIME: 63.12 SCOTTISH CHAMBER ORCHESTRA ROBIN TICCIATI conductor 2 Recorded at Usher Hall, Edinburgh UK from 7th – 10th October 2011 Produced by Philip Hobbs Engineered by Philip Hobbs & Calum Malcolm Assistant Engineer: Robert Cammidge Post-production by Julia Thomas, Finesplice, UK Julio de Diego image reproduced with permission from the Hector Berlioz Website (www.hberlioz.com) Photos of Robin Ticciati by Marco Borggreve Photo of SCO by Chris Christodoulou The ‘Overture’ from Béatrice et Bénédict is published by BÄRENREITER-VERLAG, KASSEL This recording was made possible with support from the SCO Sir Charles Mackerras Fund 3 Symphonie Fantastique (183 0–1832) FOR A LONG TIME the controversy surrounding the Symphonie Fantastique prevented a thorough and sensible examination of the music itself – a serious analysis of what was in it and how it was put together. Yet Berlioz was certainly not the first or the last composer to re-use existing material (think of Beethoven, think of Brahms) – or to find musical stimulus in literary sources: in this case, the writings of Chateaubriand, Goethe and Victor Hugo. In one of the poems in Hugo’s Odes et Ballades the striking of midnight on a monastery bell precipitates a hideous assembly of witches and half-human, half-animal creatures who execute a whirling round-dance and perform obscene parodies of the rituals of the church, an image that Berlioz transmutes into his highly original and skilfully constructed finale. -

Les Nuits D'été & La Mort De Cléopâtre

HECTOR BERLIOZ Les nuits d'été & La mort de Cléopâtre SCOTTISH CHAMBER ORCHESTRA ROBIN TICCIATI CONDUCTOR KAREN CARGILL MEZZO-SOPRANO HECTOR BERLIOZ Les nuits d’été & La mort de Cléopâtre Scottish Chamber Orchestra Robin Ticciati conductor Karen Cargill mezzo-soprano Recorded at Cover image The Usher Hall, Dragonfly Dance III by Roz Bell Edinburgh, UK 1-4 April 2012 Session photos by John McBride Photography Produced and recorded by Philip Hobbs All scores published by Bärenreiter-Verlag, Kassel Assistant engineer Robert Cammidge Design by gmtoucari.com Post-production by Julia Thomas 2 Les nuits d’été 1. Villanelle ......................................................................................2:18 2. Le spectre de la rose .................................................................6:12 3. Sur les lagunes ............................................................................5:50 4. Absence ......................................................................................4:45 5. Au cimetière ...............................................................................5:32 6. L’île inconnue .............................................................................3:56 Roméo & Juliette 7. Scène d’amour ........................................................................16:48 La mort de Cléopâtre 8. Scène lyrique ..............................................................................9:57 9. Méditation.................................................................................10:08 Total Time: ......................................................................................65:48 -

Symphonien 3, 4 & 9

MAHLER SYMPHONIEN 3, 4 & 9 Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks Bernard Haitink Symphonie Nr. 3 d-Moll / Symphony No. 3 in D minor für Alt-Solo, Knabenchor, Chor und Orchester for alto solo, boys‘ choir, choir and orchestra CD 1 Erste Abteilung 01 I. Kräftig. Entschieden 35:49 CD 2 Zweite Abteilung 01 II. Tempo di Menuetto. Sehr mäßig. Ja nicht eilen! 10:06 02 III. Comodo. Scherzando. Ohne Hast 17:53 03 IV. Sehr langsam. Misterioso. Durchaus ppp („Oh Mensch! Gib Acht!“) 9:34 04 V. Lustig im Tempo und keck im Ausdruck („Es sungen drei Engel“) 4:26 05 VI. Langsam. Ruhevoll. Empfunden 23:40 Total time CD 1 & CD 2: 101:28 Gerhild Romberger Mezzosopran / mezzo soprano Augsburger Domsingknaben / Reinhard Kammler Einstudierung / chorus master Martin Angerer Posthorn-Solo / post horn Chor und Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks Yuval Weinberg Einstudierung / chorus master / Bernard Haitink Dirigent / conductor Live-Aufnahme / live recording: München, Philharmonie im Gasteig, 16./17.06.2016 · Tonmeister/Recording Producer & Schnitt/Editing: Bernhard Albrecht · Toningenieur/Recording Engineer: Peter Urban · Verlag / Publisher: Hrsg. Erwin Ratz und Karl Heinz Füssl © Universal Edition AG, Wien mit freundlicher · Genehmigung von SCHOTT MUSIC, Mainz Gustav Mahler, Toblach 1909 Symphonie Nr. 4 G-Dur Symphonie Nr. 9 D-Dur Symphony No. 4 in G major Symphony No. 9 in D major CD 3 CD 4 01 Bedächtig. Nicht eilen 17:24 01 Andante comodo 26:47 02 In gemächlicher Bewegung. Ohne Hast 9:05 02 Im Tempo eines gemächlichen Ländlers. 03 Ruhevoll 20:40 Etwas täppisch und sehr derb 16:08 04 Sehr behaglich 03 Rondo-Burleske. -

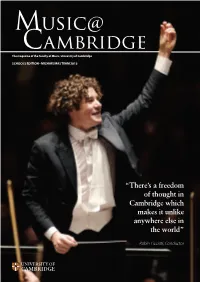

“There's a Freedom of Thought in Cambridge Which Makes It Unlike

The magazine of the Faculty of Music, University of Cambridge SCHOOLS EDITION - MICHAELMAS TERM 2015 “There’s a freedom of thought in Cambridge which makes it unlike anywhere else in the world” Robin Ticciati, Conductor Contents “Music is a moral law. It gives soul to the universe, Primed for success 4 wings to the Alumni share their stories mind, flight to The low-down 10 Applying to Cambridge the imagination , A place to call your own 14 and charm and Choosing a college gaiety to life and Tradition and innovation 16 The Cambridge Music course to everything.” Performance in the Music Faculty 20 Plato The broader context Best of both worlds 21 The CAMRAM scheme explained Calling all composers… 22 Music@Cambridge New music in Cambridge Michaelmas 2015 Composing to connect 23 Music to change the world Published by Faculty of Music 11 West Road, Cambridge CB3 9DP Glittering prizes 24 Music awards at Cambridge A society for all seasons 32 www.mus.cam.ac.uk A year in the life of CUMS [email protected] Joining Forces 33 Britten’s War Requiem remembered @camunimusic Bringing the experts on-side 34 Creative collaboration with the AAM facebook.com/cambridge.universitymusic Different Strokes 35 Learning through lectures Commissioning Editors: Beyond the ivory tower 38 Martin Ennis, Sarah Williams The Cambridge outreach programme Editor: They shoot, he scores 39 E. Jane Dickson Music for film and screen Graphic design: Careers 40 Matt Bilton, Pageworks Life beyond Cambridge Meet the staff 42 Printed by The Lavenham Press Ltd Arbons House 47 Water Street Lavenham Suffolk CO10 9RN on the cover Robin Ticciati ©Marco Borggreve Welcome usty folios, fusty But what’s so special about studying Music at dons. -

Bibliography – 2020

RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY 1996 TO THE PRESENT (2020) Compiled in 2012 by: Paulina Piedzia Colón, Devora Geller, Danya Katok, Imani Mosley, Austin Shadduck, Maksim Shtrykov, and Serena Wang Edited by: Paulina Piedzia Colón and Devora Geller (2012–17) David Manning (2018–) Introduction by: Allan Atlas CONTENTS Introduction 1 A. Publications of Music 5 B. Collections of Vaughan Williams’s Writings 9 C. Bibliographical/Discographical 10 D. Correspondence 12 E. Iconography 14 F. Biography/Life-and-Works Surveys 15 G. Collections of essays devoted entirely/mainly to Vaughan Williams 21 H. Analysis/Criticism of Individual Works and Genres 24 H.a. Folk song 24 H.b. Hymnody 28 H.c. Opera/Other Stage Works 30 H.d. Choral Music 36 H.e. Songs 40 H.f. Symphonies 45 H.g. Concertos and solo instrument with orchestra 52 H.h. Other Orchestral Music 56 H.i. Band Music 59 H.j. Film Music 61 H.k. Chamber Music, Solo Piano, Organ 63 I. Contextual/Sociological 66 Author Index 81 Ralph Vaughan Williams: An Annotated Bibliography 1996 to the Present (2020) INTRODUCTION When the first installment of this bibliography appeared in Spring 2013, there were four such compilations devoted to the scholarly literature on Ralph Vaughan Williams. The earliest of these was Peter Starbuck’s bibliography of 1967, which lists both writings by and about Vaughan Williams.1 Rather more extensive was Neil Butterworth’s 1990 Ralph Vaughan Williams: A Guide to Research, which includes 564 items, though some of these are somewhat shaky in terms of scholarly -

Roméo Et Juliette

HECTOR BERLIOZ Roméo et Juliette ROBIN TICCIATI CONDUCTOR SWEDISH RADIO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA & SWEDISH RADIO CHOIR HECTOR BERLIOZ (1803–1869) Roméo et Juliette DRAMATIC SYMPHONY FOR SOLOISTS, CHORUS AND ORCHESTRA, OP. 17 Robin Ticciati conductor Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra Swedish Radio Choir Katija Dragojevic mezzo-soprano Andrew Staples tenor Alastair Miles bass Recorded live at concerts in the Berwaldhallen, Stockholm, Sweden, 3–8 November 2014 Produced by Philip Hobbs Recorded by Philip Hobbs and Johan Hyttnäs Post-production by Julia Thomas Cover image by Karen Taddeo Design by gmtoucari.com Edition by D. Kern Holoman (Bärenreiter, 1990) 1 Disc 1 No. 1 1. Introduction instrumentale : Combats – Tumulte – Intervention du Prince ....................................... 4:43 2. Prologue : Récitatif harmonique : « D’anciennes haines endormies » ............... 5:11 3. Strophes : « Premiers transports que nul n’oublie! » ............................ 6:01 4. « Bientôt de Roméo » – Scherzetto vocal : « Mab, la messagère » ... 3:20 No. 2 : Andante et Allegro 5. Roméo seul. Tristesse – Bruit lontain de bal et de concert ................. 6:57 6. Grande fête chez Capulet .................................................................... 5:55 No. 3 : Scène d’amour 7. Nuit sereine. Le jardin de Capulet, silencieux et désert ................... 18:53 Disc 2 No. 4 : Scherzo 1. La reine Mab, ou la Fée des songes ..................................................... 8:10 No. 5 : Convoi funèbre de Juliette 2. « Jetez des fleurs pour la vierge expirée! » ........................................... 9:29 No. 6 : Roméo au tombeau des Capulets 3. Roméo au tombeau des Capulets ...................................................... 1:33 4. Invocation – Réveil de Juliette – Joie délirante, désespoir, dernières angoisses et mort des deux amants .................................... 6:18 No. 7 : Final 5. La foule accourt au cimetière – Rixe des Capulets et des Montagus .................................................................................... -

The Cambridge Companion To: the ORCHESTRA

The Cambridge Companion to the Orchestra This guide to the orchestra and orchestral life is unique in the breadth of its coverage. It combines orchestral history and orchestral repertory with a practical bias offering critical thought about the past, present and future of the orchestra as a sociological and as an artistic phenomenon. This approach reflects many of the current global discussions about the orchestra’s continued role in a changing society. Other topics discussed include the art of orchestration, score-reading, conductors and conducting, international orchestras, and recording, as well as consideration of what it means to be an orchestral musician, an educator, or an informed listener. Written by experts in the field, the book will be of academic and practical interest to a wide-ranging readership of music historians and professional or amateur musicians as well as an invaluable resource for all those contemplating a career in the performing arts. Colin Lawson is a Pro Vice-Chancellor of Thames Valley University, having previously been Professor of Music at Goldsmiths College, University of London. He has an international profile as a solo clarinettist and plays with The Hanover Band, The English Concert and The King’s Consort. His publications for Cambridge University Press include The Cambridge Companion to the Clarinet (1995), Mozart: Clarinet Concerto (1996), Brahms: Clarinet Quintet (1998), The Historical Performance of Music (with Robin Stowell) (1999) and The Early Clarinet (2000). Cambridge Companions to Music Composers -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89611-5 - The Cambridge History of Musical Performance Colin Lawson and Robin Stowell Frontmatter More information THE CAMBRIDGE HISTORY OF MUSICAL PERFORMANCE The intricacies and challenges of musical performance have recently attracted the attention of writers and scholars to a greater extent than ever before. Research into the performer’s experience has begun to explore such areas as practice techniques, performance anxiety and memorisation, as well as many other professional issues. Historical performance practice has been the subject of lively debate way beyond academic circles, mirroring its high profile in the recording studio and the concert hall. Reflecting the strong ongoing interest in the role of performers and performance, this History brings together research from leading scholars and historians, and, impor- tantly, features contributions from accomplished performers, whose practi- cal experiences give the volume a unique vitality. Moving the focus away from the composers and onto the musicians responsible for bringing the music to life, the History presents a fresh, integrated and innovative perspec- tive on performance history and practice, from the earliest times to today. COLIN LAWSON is Director of the Royal College of Music, London. He has an international profile as a period clarinettist and has played principal in most of Britain’s leading period orchestras, notably The Hanover Band, the English Concert and the London Classical Players, with whom he has recorded extensively and toured worldwide. He has published widely, and is co-editor, with Robin Stowell, of a series of Cambridge Handbooks to the Historical Performance of Music, for which he co-authored an introductory volume and contributed a book on the early clarinet. -

The Young Conductor Looks to the Future

THE WORLD’S BEST CLASSICAL MUSIC REVIEWS Est 1923 . APRIL 2018 gramophone.co.uk Robin Ticciati The young conductor looks to the future PLUS Paul Lewis explores Haydn’s piano sonatas Handel’s Saul: the finest recordings UNITED KINGDOM £5.75 Intimate concerts featuring internationally acclaimed classical musicians in central London Now Booking Until July 2018 Igor Levit Cuarteto Casals: Beethoven Cycle Roderick Williams: Exploring Schubert’s Song Cycles O/Modernt: Purcell from the Ground Up Haydn String Quartet Series Jörg Widmann as Composer-Performer and much more… The Wigmore Hall Trust 36 Wigmore Street, London W1U 2BP Director: John Gilhooly OBE www.wigmore-hall.org.uk Registered Charity Number 1024838 A special eight-page section focusing on recent recordings from the US and Canada JS Bach Solo Violin Sonatas and Partitas, BWV1001-1006 talks to ... Johnny Gandelsman vn In a Circle F b ICR101 (124’ • DDD) Johnny Gandelsman The violinist and co-founder Bach’s Violin of Brooklyn Rider discusses his Sonatas and debut solo recording of Bach Partitas are among the most frequently Was it a challenge to plunge straight into performed works for the instrument, Bach for your first solo recording? or any instrument. Recordings evince a Not really. Over the the last three years spectrum of approaches, from historical I’ve performed all six Sonatas and Partitas treatments on period instruments to in concert about 30 times, which has been concepts Romantic and beyond. deeply rewarding. I wanted to capture this Among the newest journeys is Johnny moment of personal learning and growth. Gandelsman’s freshly considered account Do you miss the collaborative process of these monuments.