The Holocaust in Slovak Drama*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{PDF} World War II: a New History Kindle

WORLD WAR II: A NEW HISTORY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Evan Mawdsley | 498 pages | 21 Sep 2009 | CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS | 9780521608435 | English | Cambridge, United Kingdom World War II: A New History PDF Book The use of the jet aircraft was pioneered and, though late introduction meant it had little impact, it led to jets becoming standard in air forces worldwide. Followers of Judaism believe in one God who revealed himself through ancient prophets. Women were recruited as maids and child- care providers. Weeks after the first successful test of the atomic bomb occurred in Alamogordo, New Mexico, on July 16, , President Harry Truman , who had ascended to the presidency less than four months earlier after the death of Franklin D. The Imperial Japanese Army used a variety of such weapons during its invasion and occupation of China see Unit [] [] and in early conflicts against the Soviets. Edje Jeter rated it it was amazing Mar 31, After 75 years, wrecked remains of a U. Concepts in Submarine Design. The fierce battle for the city named after Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin resulted in nearly two million casualties, including the deaths of tens of thousands of Stalingrad residents. Retrieved 19 January The Logic of Political Survival. Archived from the original on 3 March Dec — Jan ". They agreed on the occupation of post-war Germany, and on when the Soviet Union would join the war against Japan. In August, Chinese communists launched an offensive in Central China ; in retaliation, Japan instituted harsh measures in occupied areas to reduce human and material resources for the communists. -

Augusten.Pdf

1 [CONTENTS] [ACE OF THE MONTH] Flight Lieutenant Eric Lock ……3 3 August 2015 - Author: Mark Barber, War Thunder Historical Consultant [NATIONAL FORCES] Philippine Air Force ……7 Author: Adam “BONKERS” Lisiewicz [VEHICLE PROFILE] Canadair CL-13 Mk 5 Sabre ……9 Author: Scott “Smin1080p” Maynard [VEHICLE PROFILE] T-50 ……12 Autor: Jan “RayPall” Kozák [HISTORICAL] Jet Engines of the Air ……16 Author: Joe “Pony51” Kudrna [GROUND FORCES] 1st Armored Division (US Army) ……19 Author: Adam “BONKERS” Lisiewicz [WARRIOR PROFILE] Dmitry Fyodorovich Lavrinenko ……23 Author: The War Thunder Team [VEHICLE PROFILE] Supermarine Seafire FR 47 ……25 Author: Sean "Gingahninja" Connell [HISTORICAL] The ShVAK Cannon ……28 Author: Jan “RayPall” Kozák [VEHICLE PROFILE] PzKpfw 38(t) Ausf. A & F ……31 Author: Joe “Pony51” Kudrna [NATIONAL FORCES] The Iraqi Air Force ……35 Author: Jan “RayPall” Kozák [VEHICLE PROFILE] Lavochkin La-7 ……39 Author: Adam “BONKERS” Lisiewicz [COMMEMORATION] Slovak National Uprising ……42 Author: Jan “RayPall” Kozák 1 _____________________________________________________________________ © 2009—2015 by Gaijin Entertainment. Gaijin and War Thunder are trademarks and/or registered trademarks of Gaijin Entertainment or its licensors, all other logos are trademarks of their respective owners. 2 Supermarine Spitfire Mk.Vb (for the Mk.IIb ingame) that served in the Royal Air Force in July 1941. Camouflage created by Luckyleprechaun | Download here [ACE OF THE MONTH] Flight Lieutenant Eric Lock 3 August 2015 - Author: Mark Barber, War Thunder Historical Consultant This year sees the 75th Anniversary of was privately educated but also spent one of the largest, critical and iconic much of his childhood immersed in air battles ever fought: the Battle of country pursuits such as horse riding. -

Joan Campion. in the Lion's Mouth: Gisi Fleischmann and the Jewish Fight for Survival

Gorbachev period) that, "As a liberal progressive reformer, and friend of the West, Gorbachev is ... a figment of Western imagination." One need not see Gorbachev as a friend or a liberal, of course, to understand that he in- tended from the outset to change the USSR in fundamental ways. To be sure, there are some highlights to this book. Chapter 4 by Gerhard Wettig (of the Bundesinstitut fiir Ostwissenschaftliche und Internationale Studien) discusses important conceptual distinctions made by the Soviets in their view of East-West relations. Finn Sollie, of the Fridtjof Nansen Institute in Norway, provides a balanced and insightful consideration of Northern Flank security issues. This is not the book it could have been given the talented people involved in the conferences that led to such a volume. Given the timing of its produc- tion (during the first two years of Gorbachev's rule), the editors should have done much more to seek up-dated and more in-depth analyses from the contributors. As it stands, Cline, Miller and Kanet have given us a foot- note in the record of a waning Cold War. Daniel N. Nelson University of Kentucky Joan Campion. In the Lion's Mouth: Gisi Fleischmann and the Jewish Fight for Survival. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1987. xii, 152 pp. $24.50 (cloth), $12.75 (paper). The immense accumulation of scholarship on the Holocaust and World War II made possible the emergence of a new genre of literature portraying heroic figures engaged in rescue work in terror-ridden Nazi Europe. The last decade has seen the publication of a spate of books including the sagas of Raoul Wallenberg, Hanna Senesh and Janusz Korczak, drawing on extensive source material as well as previous literature. -

Čierny Slnovrat)

A Black Solstice (Čierny slnovrat) Author: Klára Jarunková First Published: 1979 Translations: Hungarian (Fekete napforduló, 1981); Czech (Černý slunovrat, 1984); Ukrainian (Čorne soncestojannja, 1985). Film Adaptation: Čierny slnovrat, TV film; screenplay Ondrej Sliacky, film director Ivan Teren, premiered 25 March 1985. About the Author: Klára Jarunková (1922–2005) was born in Červená Skala in the Slo- vakian mountains Low Tatras. When she was eight years old, her mother died. She graduated from the high school in Banská Bystrica, she never finished her studies of Slovak and philosophy at Comenius University in Bratislava. From 1940 to 1943, she worked as a teacher near her birthplace. After the war, she was a clerk, an editor for the Czechoslovak Radio and the satirical magazine Roháč. She wrote many successful books for children and novels for girls and teenagers. They were often translated into foreign languages. The basis of the fictional world of her works is often a confronta- tion between children and adults as seen through children’s eyes. Content and Interpretation The novel, consisting of 16 chapters, is situated in Central Slovakia, Banská Bystrica and its surroundings, at the end of World War II, from November 1944 to March 1945. The historical background of the plot is the Slovak National Uprising against the clerofascist regime in Slovakia connected with Hitler’s Germany. The heart of the up- rising was Banská Bystrica. The uprising broke out at the end of August 1944, but the Nazi army, supported by Slovak collaborators, started a counter-offensive. At the end of October 1944, German troops had also taken Banská Bystrica. -

Gadol Beyisrael Hagaon Hakadosh Harav Chaim Michoel Dov

Eved Hashem – Gadol BeYisrael HaGaon HaKadosh HaRav Chaim Michoel Dov Weissmandel ZTVK "L (4. Cheshvan 5664/ 25. Oktober 1903, Debrecen, Osztrák–Magyar Monarchia – 6 Kislev 5718/ 29. November 1957, Mount Kisco, New York) Евед ХаШем – Гадоль БеИсраэль ХаГаон ХаКадош ХаРав Хаим-Михаэль-Дов Вайсмандель; Klenot medzi Klal Yisroel, Veľký Muž, Bojovník, Veľký Tzaddik, vynikajúci Talmid Chacham. Takýto človek príde na svet iba raz za pár storočí. „Je to Hrdina všetkých Židovských generácií – ale aj pre každého, kto potrebuje príklad odvážneho človeka, aby sa pozrel, kedy je potrebná pomoc pre tých, ktorí sú prenasledovaní a ohrození zničením v dnešnom svete.“ HaRav Chaim Michoel Dov Weissmandel ZTVK "L, je najväčší Hrdina obdobia Holokaustu. Jeho nadľudské úsilie o záchranu tisícov ľudí od smrti, ale tiež pokúsiť sa zastaviť Holokaust v priebehu vojny predstavuje jeden z najpozoruhodnejších príkladov Židovskej histórie úplného odhodlania a obete za účelom záchrany Židov. Nesnažil sa zachrániť iba niektorých Židov, ale všetkých. Ctil a bojoval za každý Židovský život a smútil za každou dušou, ktorú nemohol zachrániť. Nadľudské úsilie Rebeho Michoela Ber Weissmandla oddialilo deportácie viac ako 30 000 Židov na Slovensku o dva roky. Zohral vedúcu úlohu pri záchrane tisícov životov v Maďarsku, keď neúnavne pracoval na zverejňovaní „Osvienčimských protokolov“ o nacistických krutostiach a genocíde, aby „prebudil“ medzinárodné spoločenstvo. V konečnom dôsledku to ukončilo deportácie v Maďarsku a ušetrilo desiatky tisíc životov maďarských Židov. Reb Michoel Ber Weissmandel bol absolútne nebojácny. Avšak, jeho nebojácnosť sa nenarodila z odvahy, ale zo strachu ... neba. Každý deň, až do svojej smrti ho ťažil smútok pre milióny, ktorí nemohli byť spasení. 1 „Prosím, seriózne študujte Tóru,“ povedal HaRav Chaim Michoel Dov Weissmandel ZTVK "L svojim študentom, "spomína Rav Spitzer. -

Thesis Front Matter

Memories of Youth: Slovak Jewish Holocaust Survivors and the Nováky Labor Camp Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies Antony Polonsky & Joanna B. Michlic, Advisors In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for Master’s Degree by Karen Spira May 2011 Copyright by Karen Spira ! 2011 ABSTRACT Memories of Youth: Slovak Jewish Holocaust Survivors and the Nováky Labor Camp A thesis presented to the Department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Waltham, Massachusetts By Karen Spira The fate of Jewish children and families is one of the understudied social aspects of the Holocaust. This thesis aims to fill in the lacuna by examining the intersection of Jewish youth and families, labor camps, and the Holocaust in Slovakia primarily using oral testimonies. Slovak Jewish youth survivors gave the testimonies to the Yad Vashem Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority in Jerusalem, Israel. Utilizing methodology for examining children during the Holocaust and the use of testimonies in historical writing, this thesis reveals the reaction of Slovak Jewish youth to anti-Jewish legislation and the Holocaust. This project contributes primary source based research to the historical record on the Holocaust in Slovakia, the Nováky labor camp, and the fate of Jewish youth. The testimonies reveal Jewish daily life in pre-war Czechoslovakia, how the youth understood the rise in antisemitism, and how their families ultimately survived the Holocaust. Through an examination of the Nováky labor camp, we learn how Jewish families and communities were able to remain together throughout the war, maintain Jewish life, and how they understood the policies and actions enacted upon them. -

Y University Library

Y university library Fortuno≠ Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies professor timothy snyder Advisor PO Box 208240 New Haven CT 06520-8240 t 203 432-1879 web.library.yale.edu/testimonies Episode 6 — Renee Hartman Episode Notes by Dr. Samuel Kassow Renee Glassner Hartman was born in 1933 in Bratislava (Pressburg in German, Poszonyi in Hungarian). She had a younger sister, Herta, born in 1935. Their parents, like Herta, were deaF. Their father was a jeweler. This is the story oF two young children who were raised in a loving, religiously observant home and who experienced the traumatic and sudden destruction oF their childhood, the loss oF their parents, and their own deportation to the notorious Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, from which they were liberated by the British in 1945. As they struggled to stay alive, Renee and Herta were inseparable. No matter how depressed and distraught she became, Renee never forgot that her younger sister, unable to hear, totally depended on her. Together they survived a long nightmare that included betrayal, physical violence, liFe-threatening disease, and hunger. During the time when Renee and Herta were born, the Jews oF Bratislava lived in relative peace and security. BeFore World War I, most Jews in Bratislava had spoken Magyar or German (German was the language in Renee’s home). Between the wars they also had to learn Slovak as Bratislava, formerly under Hungarian administration, became part oF the new Czechoslovak state, which was founded in 1918. Under the leadership oF President Thomas Masaryk, Czechoslovakia was a democracy, and somewhat more prosperous than countries like Poland and Hungary. -

75Th Anniversary Slovak National Uprising Memorial Weekend

75th anniversary Slovak National Uprising Memorial Weekend Twin Cities, Minnesota, United States August 24-25, 2019 In Bratislava, the Most Slovenského Narodného An International Conference and Remembrance Povstania , or Slovak National Uprising Bridge, has spanned the Danube River since 1972. Reception and Documentary Film, Saturday, August 24 Mississippi Room, Minnesota Genealogy Society Conference Center, Mendota Heights 2:00pm Introductory remarks and welcome 2:10pm A viewing of a Dušan Hudec documentary about the Slovak National Uprising 4:10pm Slovaks & Poles - Rising Together Two 1944 Uprising Stories 4:30pm Informal light reception and refreshments for members of sponsoring groups International Conference Sunday August 25 C.S.P.S. Hall, St. Paul 7:30am Registration, Coffee & Koláče 8:15am National Anthems United States of America and The Slovak Republic Tamara Mecum, trumpeter 8:30am Opening and Introduction of Sponsors Mark Dillon, First Vice President, CGSI Ladislava Begec̹, Consul General of the Slovak Republic in New York Kevin Hurbanis, President, Czechoslovak Genealogical Society International (CGSI) Cecilia Rokusek, President and CEO, National Czech & Slovak Museum & Library David Stepan, President, Czech and Slovak Sokol Minnesota Renata Ticha, President, Czech and Slovak Cultural Center of Minnesota Karen Varian, President, Rusin Association of Minnesota 8:45am Setting the Historical Context- How the Slovak State (Slovenský Štát) Came to Be and Why It Provoked an Uprising Dr. John Palka, Professor Emeritus, University of Washington, grandson of Milan Hodža, Prime Minister of Czechoslovakia 9:15am Nationalism, National Identity and the Slovak National Uprising Dr. Nadya Nedelsky, Chair, International Studies Department, Macalester College 9:45am to 10am Break 10:00am First Keynote Address The Importance of The Uprising After 75 Years Juraj Lepiš Historian and Researcher, Museum of Slovak National Uprising, Banská Bystrica, Slovakia 11:00am Presentation of the 15th Annual Prize of Milan Hodža 11:15am Lunch Served in C.S.P.S. -

The Tragedy of Slovak Jews

TRAVELING EXHIBIT INFORMATION The Tragedy of Slovak Jews The Tragedy of Slovak Jews tells the true story of the Jew- 80,000 Slovak Jews. The Slovak government deported almost ish holocaust in Slovakia. Researched and prepared by 58,000 Jews from Slovakia to Nazi extermination camps The Museum of the Slovak National Uprising in from March to October 1942. Slovakia paid 500 Reich Marks Banská Bystrica, Slovakia, the first public exhibition of for each deported Jew as an evacuation fee. An additional The Tragedy of Slovak Jews opened in 2002 at the Aus- 14,000 persons were transported to Auschwitz and Terezin chwitz – Birkenau State Museum in Auschwitz, Poland, in the second wave of deportations from September 30 to where it is still on display today. In 2004, the NCSML November 2, 1944. German military units and members of partnered with the Museum of the Slovak National Upris- the Flying Squads of Hlinka’s Guards tortured and killed more ing to translate it into English. The first exhibtion in the than 5,300 persons (civilians, Roma and other racially per- United States was at the National Czech & Slovak secuted persons) after the repression of the Slovak National Museum & Library in Cedar Rapids, IA November 4, 2005 Uprising in 1944 –1945. The victims were found in 211 mass to February 26, 2006. graves and more than 90 villages were burned down. The Tragedy of Slovak Jews examines the holocaust in rela- 3rd Section: Slovak Jews in Nazi Concentration Camps tion to the development of Slovak society and the regime of (1942 - 1945) This unit documents the life of prisoners in the the Slovak war republic in the years 1938 – 1945. -

Teacher's Guide

TEACHER’S GUIDE TEACHER’S GUIDE Daring to Resist: Jewish Defiance in the Holocaust TABLE OF CONTENTS Curator’s Introduction, by Yitzchak Mais Teaching a New Approach to the Holocaust: The Jewish Narrative 2 How to Use this Guide 4 Classroom Lesson Plan for Pre-Visit Activities (for all schools) 5 Responding to the Nazi Rise to Power 8 On Behalf of the Community 10 Documenting the Unimaginable 12 Physical and Spiritual Resistance 14 Pre- or Post-Visit Lesson Plans (for Jewish schools) 16 Maintaining Jewish Life: The Resistance of Rabbi Ephraim Oshry 17 Resistance of the Working Group: Rabbi Michael Dov Ber Weissmandel and Gisi Fleischmann 25 Ethical Wills from the Holocaust: A Final Act of Defiance 36 Additional Resources 48 Photo Credits 52 This Teacher’s Guide is made possible through the generous support of the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany: The Rabbi Israel Miller Fund for Shoah Research, Documentation and Education. TEACHER’S GUIDE / DARING TO RESIST: Jewish Defiance in the Holocaust 1 Curator’s Introduction — by Yitzchak Mais TEACHING A NEW APPROACH TO THE HOLOCAUST: THE JEWISH NARRATIVE ix decades after the liberation of Auschwitz, the Holocaust is indisputably recognized as a watershed event whose ramifications have critical significance for Jews and non-Jews alike. As educators we are deeply concerned with how the Holocaust has been absorbed into the historical consciousness of Ssociety at large, and among Jews in particular. Awareness of the events of the Holocaust has dramatically increased since the 1980s, with a surge of books, movies, and educational curricula, as well as the creation of Holocaust memorials, museums, and exhibitions worldwide. -

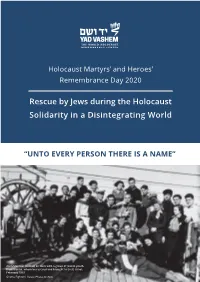

Rescue by Jews During the Holocaust Solidarity in a Disintegrating World

Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Day 2020 Rescue by Jews during the Holocaust Solidarity in a Disintegrating World “UNTO EVERY PERSON THERE IS A NAME” Aron Menczer (center) on deck with a group of Jewish youth from Vienna, whom he rescued and brought to Eretz Israel, February 1939 Ghetto Fighters’ House Photo Archive Jerusalem, Nissan 5780 April 2020 “Unto Every Person There Is A Name” Public Recitation of Names of Holocaust Victims in Israel and Abroad on Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Day “Unto every person there is a name, given to him by God and by his parents”, wrote the Israeli poetess Zelda. Every single victim of the Holocaust had a name. The vast number of Jews who were murdered in the Holocaust – some six million men, women and children - is beyond human comprehension. We are therefore liable to lose sight of the fact that each life that was brutally ended belonged to an individual, a human being endowed with feelings, thoughts, ideas and dreams whose entire world was destroyed, and whose future was erased. The annual recitation of names of victims on Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Day is one way of posthumously restoring the victims’ names, of commemorating them as individuals. We seek in this manner to honor the memory of the victims, to grapple with the enormity of the murder, and to combat Holocaust denial and distortion. This year marks the 31st anniversary of the global Shoah memorial initiative “Unto Every Person There Is A Name”, held annually under the auspices of the President of the State of Israel. -

The Holocaust As Public History

The University of California at San Diego HIEU 145 Course Number 646637 The Holocaust as Public History Winter, 2009 Professor Deborah Hertz HSS 6024 858 534 5501 Class meets 12---12:50 in Center 113 Please do not send me email messages. Best time to talk is right after class. It is fine to call my office during office hours. You may send a message to me on the Mail section of our WebCT. You may also get messages to me via Ms Dorothy Wagoner, Judaic Studies Program, 858 534 4551; [email protected]. Office Hours: Wednesdays 2-3 and Mondays 11-12 Holocaust Living History Workshop Project Manager: Ms Theresa Kuruc, Office in the Library: Library Resources Office, last cubicle on the right [turn right when you enter the Library] Phone: 534 7661 Email: [email protected] Office hours in her Library office: Tuesdays and Thursdays 11-12 and by appointment Ms Kuruc will hold a weekly two hour open house in the Library Electronic Classroom, just inside the entrance to the library to the left, on Wednesday evenings from 5-7. Students who plan to use the Visual History Archive for their projects should plan to work with her there if possible. If you are working with survivors or high school students, that is the time and place to work with them. Reader: Mr Matthew Valji, [email protected] WebCT The address on the web is: http://webct.ucsd.edu. Your UCSD e-mail address and password will help you gain entry. Call the Academic Computing Office at 4-4061 or 4-2113 if you experience problems.