Wath Mill Upper Nidderdale Landscape Partnership

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glasshouses C P School Glasshouses Harrogate North Yorkshire HG3

Glasshouses C P School Glasshouses Harrogate North Yorkshire HG3 5QH 01423 711440 [email protected] Learning Together, Achieving Together, Respecting Each Other Headteacher: Miss Nicola Thornber NPQH, BA (hons) QTS 13 November 2021 Dear parents/carers As many of you will remember from our consultation meeting held prior to the first lockdown, the Primary Schools in Nidderdale have been considering forming a federation for some time to ensure the future stability of education in the Dale, and have been looking at various different options. Recently, the Executive Headeacher at St Cuthbert’s and Fountains Earth has announced that she is leaving her current post with effect from Easter 2021. In light of this, we are now looking at forming a federation of three schools (Glasshouses, St Cuthbert’s and Fountains Earth), which will hopefully take place either in September 2021 or January 2022. Following discussion between governors at all schools, and working closely with the Local Authority, I am delighted to announce that as from January, Nicola Thornber will begin a handover process with the outgoing head at St Cuthbert’s/Fountains Earth, and on Monday 12th April she will become acting head of all three schools; St Cuthbert’s and Fountains Earth Federation and Glasshouses. Once the federation formally takes place, she will become permanent head of the federation. This is great news for Glasshouses School - it reflects the hard work and success that Miss Thornber has achieved during her time as headteacher here. Further communication will be shared with parents in due course regarding this, together with information about how the changes will impact Glasshouses School from January, when the handover process will commence. -

Otley Walking Festival 2015.Qxp 26/04/2021 18:56 Page 1

m o c . r e t a w e r i h s k r o y . w w M w 1 k u . o c . l a v i t s e f g n i k l a w y e l t o . w w w r e t a W s ’ e r i h s k r o Y g n i y l p p u S 2 6 M M M 6 1 2 0 2 Y L U J 4 – E N U J 6 2 6 A 2 1 0 1 6 s d e e L d r o f d a r B M 1 A 6 5 A 5 6 8 6 A 4 0 6 6 A A 6 N 0 3 8 9 5 6 A y e l t O 1 2 0 2 l a v i t s e F g n i k l a W y e l t O k r o Y y e l k l I g n i r o s n o p S e t a g o r r a H 5 6 A r e t a W e r i h s k r o Y n o t p i k S y r a s r e v i n n A h t 0 2 e h T m o c . y r e k a b e t a g d n o b @ o f n i : l i a m E 6 1 5 7 6 4 - 3 4 9 1 0 : l e T y e l t O , e t a g d n o B 0 3 1 2 0 2 6 1 0 2 s d r a w A p o h S m r a F & i l e D e h t t a y r e k a B t s e B L A V I T S E F f o s r e n n i W s e v i t a v r e s e r p r o s e v i t i d d a t u o h t i w d n a h y b e d a m s e x o b d a l a s & s c i n c i p G N I K L A W s e i r u o v a s d n a s e k a c , s d a e r b t s i l a i c e p S ' y t i r g e t n I h t i w g n i k a B ' y r e k a B e t a g d n o B Y E L T O . -

Der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr

26 . 3 . 84 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 82 / 67 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . Februar 1984 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75 /268 / EWG ( Vereinigtes Königreich ) ( 84 / 169 / EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN GEMEINSCHAFTEN — Folgende Indexzahlen über schwach ertragsfähige Böden gemäß Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe a ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden bei der Bestimmung gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro jeder der betreffenden Zonen zugrunde gelegt : über päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft , 70 % liegender Anteil des Grünlandes an der landwirt schaftlichen Nutzfläche , Besatzdichte unter 1 Groß vieheinheit ( GVE ) je Hektar Futterfläche und nicht über gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG des Rates vom 65 % des nationalen Durchschnitts liegende Pachten . 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berggebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebieten ( J ), zuletzt geändert durch die Richtlinie 82 / 786 / EWG ( 2 ), insbe Die deutlich hinter dem Durchschnitt zurückbleibenden sondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2 , Wirtschaftsergebnisse der Betriebe im Sinne von Arti kel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe b ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden durch die Tatsache belegt , daß das auf Vorschlag der Kommission , Arbeitseinkommen 80 % des nationalen Durchschnitts nicht übersteigt . nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments ( 3 ), Zur Feststellung der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe c ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG genannten geringen Bevöl in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : kerungsdichte wurde die Tatsache zugrunde gelegt, daß die Bevölkerungsdichte unter Ausschluß der Bevölke In der Richtlinie 75 / 276 / EWG ( 4 ) werden die Gebiete rung von Städten und Industriegebieten nicht über 55 Einwohner je qkm liegt ; die entsprechenden Durch des Vereinigten Königreichs bezeichnet , die in dem schnittszahlen für das Vereinigte Königreich und die Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten Gebiete Gemeinschaft liegen bei 229 beziehungsweise 163 . -

This Is a Copy of the Sealed Order

THIS IS A COPY OF THE SEALED ORDER NORTH YORKSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL (VARIOUS ROADS, BOROUGH OF HARROGATE) (PARKING AND WAITING) (NO 2) ORDER 2003 North Yorkshire County Council (hereinafter referred to as "the Council") in exercise of their powers under Sections 1(1), 2(1) to (3) and 4(2) of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984 ("the Act") and of all other enabling powers and after consultation with the Chief Officer of Police in accordance with Part III of Schedule 9 to the Act, hereby make the following Order:- PART 1 GENERAL 1. (1) When used in this Order each of the following expressions has the meaning assigned to it below:- “disabled person” means a person who holds a disabled persons’ badge in accordance with the provisions of the Disabled Persons (Badges for Motor Vehicles) (England) Regulations 2000 (No. 682) (and in particular Regulation 4 thereof) or any re-enactment thereto; “disabled person’s badge” means a badge issued in accordance with the provisions of the Disabled Persons (Badges for Motor Vehicles) (England) Regulations 2000 (as amended) (in particular Regulation 11 and the Schedule thereto) or under regulations having effect in Scotland and Wales under Section 212 of the Chronically Sick and Disabled Persons Act 1970 as referred to currently by the Local Authorities Traffic Orders (Exemptions for Disabled Persons) (England) Regulations 2000 (No. 683) or any subsequent further re- enactments thereof; “disabled person’s vehicle” means a vehicle driven by a disabled person as defined in Regulation 4(2) of the Disabled Persons (Badges for Motor Vehicles) (England) Regulations 2000 (No. -

North West Yorkshire Level 1 Strategic Flood Risk Assessment Volume II: Technical Report

North West Yorkshire Level 1 Strategic Flood Risk Assessment Volume II: Technical Report FINAL Report July 2010 Harrogate Borough Council with Craven District Council and Richmondshire District Council North West Yorkshire Level 1 SFRA Volume II: Technical Report FINAL Report July 2010 Harrogate Borough Council Council Office Crescent Gardens Harrogate North Yorkshire HG1 2SG JBA Office JBA Consulting The Brew House Wilderspool Park Greenall's Avenue Warrington WA4 6HL JBA Project Manager Judith Stunell Revision History Revision Ref / Date Issued Amendments Issued to Initial Draft: Initial DRAFT report Linda Marfitt 1 copy of report 9th October 2009 by email (4 copies of report, maps and Sequential Testing Spreadsheet on CD) Includes review comments from Linda Marfitt (HBC), Linda Marfitt (HBC), Sian John Hiles (RDC), Sam Watson (CDC), John Hiles Kipling and Dan Normandale (RDC) and Dan Normandale FINAL report (EA). (EA) - 1 copy of reports, Floodzones for Ripon and maps and sequential test Pateley Bridge updated to spreadsheet on CD) version 3.16. FINAL report FINAL report with all Linda Marfitt (HBC) - 1 copy 9th July 2010 comments addressed of reports on CD, Sian Watson (CDC), John Hiles (RDC) and Dan Normandale (EA) - 1 printed copy of reports and maps FINAL Report FINAL report with all Printed copy of report for Linda 28th July 2010 comments addressed Marfitt, Sian Watson and John Hiles. Maps on CD Contract This report describes work commissioned by Harrogate Borough Council, on behalf of Harrogate Borough Council, Craven District Council and Richmondshire District Council by a letter dated 01/04/2009. Harrogate Borough Council‟s representative for the contract was Linda Marfitt. -

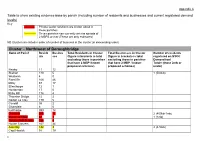

Cluster – North/West of Boroughbridge

Appendix A Table to show existing evidence base by parish (including number of residents and businesses and current registered demand levels) Key: ----------- Private sector solutions are known about in these parishes *----------- These parishes can currently access speeds of 2 MBPS or mor (These are only estimates) NB Clusters are listed in order of number of business in the cluster (in descending order) Cluster – North/west of Boroughbridge Name of Parish Reside Busines Total Residents in Cluster Total Businesses in Cluster Number of residents nts ses (figure in brackets is total (figure in brackets is total registered on NYCC excluding those in parishes excluding those in parishes Demand tool that have 2 MBP /known that have 2 MBP / known Total= (those 2mb or proposed schemes) proposed schemes) under) Newby 11 12 Skelton 140 5 1 (500kb) Westwick 4 0 Roecliffe 106 46 Milby 67 17 Ellenthorpe 12 1 Humberton 17 0 Kirby Hill 176 4 Thornton Bridge 12 2 Norton Le Clay 179 5 Cundall 39 2 Givendale 8 0 Lanthorpe 353 12 Dishforth 286 11 2 (400kb-1mb) Marton le Moor 84 1 1 (1mb) Rainton with Newby 156 4 Hutton Conyers 107 34 Assenby 132 3 2 (4-5mb) Copt Hewick 97 19 1 Bridge Hewick 19 5 Total 2005 (1873) - (1,347) 183 (180) - (164) Total = (6) RECOMMENDATION FOR NORTH/WEST OF BOROUGHBRIDGE CLUSTER: Do not prioritise for PRG funding at this stage because at least three of the parishes have an identified private sector solution, with potential for more. HBC to engage with private sector partner to try and establish full cluster scheme if possible. -

Download Club Constitution, Rules and By-Laws

NIDDERDALE ANGLING CLUB Nidderdale Angling Club has provided fine brown trout and grayling fishing for local and visiting anglers to the Dale for over a hundred years. The club will continue to do this for the benefit of future generations by good fishery management and by adopting rules, by-laws, and policies that encourage angling practices sympathetic to the conservation of fish species native to the river. The club constitution, rules, and fishing by-laws below are also posted on the club website at www.nidderdaleac.co.uk. No liability will be accepted by the Club for any accident to Members, Season Ticket Holders, Guests or Day Ticket Holders. IMPORTANT MESSAGE TO NIDDERDALE ANGLING CLUB MEMBERS Following changes in the way insurance companies manage liability claims our insurers require the club to advise them immediately following incidents in which they may have an interest especially incidents involving personal injury. In order to comply with these changes any member who is involved in an incident whilst angling or on any fishery must immediately report the circumstances to the General Secretary on 07 971 873 746 NAC FISHING BY-LAWS 1. Juniors under 14 must be accompanied by an adult. The adult must be within easy calling distance and reach at all times and must be responsible for the behaviour and safety of the junior. 2. The NAC Trout season opens on 25th March and closes on 30th September. The Grayling season opens on 16th June and closes on March14th. Scar House opens on March 25th. 3. Day tickets will usually be available to the public from 25th March to 14th March. -

Wheel Easy Ride Report 541

Sunday, September 18, 2016 Wheel Easy Ride Report 541 Short Ride There were only four of us for the short ride today but it is quality not quantity that counts. So Dennis, Corinne and Malcolm joined me for a jaunt through the sunny countryside. Having been warned that the area around Beckwithshaw would be busy with a Harrogate Harriers Trail Race we opted for Oakdale Bridge and Pennypot Lane, but with Pot Bank closed for the race Pennypot was even more than usual a busy race track. But we survived and turned off to cross the A59 at the Black Bull, the swooped down into Kettlesing. We dawdled along quiet sunlit back lanes coming across the house with a magnificent flower display (photo), and arrived at Clapham Green before making haste for the inevitable Sophie Stop at Hampsthwaite. Lots of cyclists were doing a Leeds 100 event and arrived but we were comfortably ensconced in the garden and were not moving whatever arrived! Soon Steve and Neeta Wilson appeared and also joined us in the garden. Eventually we headed homeward along Hollybank Lane and the Greenway. Twenty exceptionally pleasant miles in the early autumn sunshine. Martin W Slow-Medium Ride There were two gents and eight ladies for today's ride and we set off for Boroughbridge in glorious sunshine. Lovely to see Ruth back with us after a little break over the summer. The route had to be changed from the one posted on the Internet as I was not sure of the way. We rode to Knaresborough, Abbey Road and turned right to the Wetherby Road. -

1 Pateley Bridge Town Council

PATELEY BRIDGE TOWN COUNCIL The Council Chamber, King Street Pateley Bridge, HG3 5LE tel: 07751 571 374 [email protected] 28th October 2020 To: All Pateley Bridge Town Councillors You are hereby summoned to attend the next meeting of the Town Council to be held on Tuesday 3rd November 2020 at 7.15pm. In accordance with Regulation 5 of The Local Authorities and Police and Crime Panels (Coronavirus) (Flexibility of Local Authority and Police and Crime Panel Meetings) (England and Wales) Regulations 2020, this meeting will be held remotely using video conferencing technology. Parishioners are welcome to attend. Please email the Clerk for information on how to do this. Laura Jowett Clerk to the Council AGENDA 1 To accept Apologies and reason for absence 2 Parishioners’ Representations 3 Councillors’ Declarations of Interest and Consideration of Dispensations 4 Minutes of the Meeting held on the 6th October 2020 5 Matters Arising (a) To receive the Clerk’s report 6 County Matters a) To receive and consider information, previously circulated, about the proposed Local Government Reorganisation of North Yorkshire 7 District Matters 8 Planning Matters (a) Applications to Harrogate Borough Council (i) 20/02909/FUL. Erection of replacement outbuilding to provide a studio and workspace at Church Green Farm, Old Church Lane, Pateley Bridge HG3 5LZ (ii) 20/03810/FUL. Installation of flue to front elevation at Cats Foot Cottage, Glasshouse, HG3 5QY. 1 (b) Decisions by Harrogate Borough Council (i) 20/02076/FUL. Demolition of conservatory. Erection of a single storey extension at Fir Grove House, Glasshouses, HG3 5QH. Permission granted subject to conditions. -

This Walk Description Is from Happyhiker.Co.Uk Ramsgill To

This walk description is from happyhiker.co.uk Ramsgill to Lofthouse Starting point and OS Grid reference Ramsgill – roadside parking at village green (SE 119710) Ordnance Survey map OS Explorer Map 298 - Nidderdale. Distance 5 miles Traffic light rating Introduction: Nidderdale missed out on a Yorkshire Dales designation when the National Park was founded in 1954, which was a pity as it is certainly scenic enough to justify inclusion. It has gained prestige however through being designated as an Area of Outstanding National Beauty in 1994. Not surprisingly, the River Nidd flows through it and this walk from Ramsgill explores a short pretty middle section of it. The walk is an easy low level 5 mile “stroll” following the Nidderdale Way, ideal for the shorter winter days or when conditions higher are unappealing. It could be linked with my Lofthouse to Scar House Reservoir walk if you wanted a longer walk of about 15 miles. The Nidderdale Way sign with its Curlew will become a familiar sight. To get to Ramsgill, heading west through Pateley Bridge on the B6265, turn right after crossing the river bridge. Ramsgill is signposted. The road follows the lengthy Gouthwaite reservoir and Ramsgill is reached shortly after its end. Park on the main road by the village green, opposite the Yorke Arms where there are convenient benches for booting up. Refreshments are a possibility at the Crown Hotel in Lofthouse but check the times (and days!) of opening. Start: Facing the Yorke Arms, turn left and walk along the road. After only 50 yards or so, after crossing the bridge, take the track on the left then fork right to follow the fingerpost for the Nidderdale Way. -

LOFTHOUSE Conservation Area Character Appraisal

LOFTHOUSE Conservation Area Character Appraisal Approved 24 March 2010 Lofthouse Conservation Area Character Appraisal - Approved March 2010 p. 31 Contents Page 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................... 1 Objectives ........................................................................................................................ 2 2. Planning policy framework ............................................................................................ 2 3 Historic development & archaeology ............................................................................. 3 4 Location & landscape setting ........................................................................................ 5 5. Landscape character .................................................................................................... 6 6. The form & character of buildings ................................................................................11 7. Character area analysis ............................................................................................. 16 Map 1: Historic development ........................................................................................... 20 Map 2: Conservation Area boundary .............................................................................. 21 Map 3: Analysis & concepts ............................................................................................. 22 Map 4: Landscape analysis ............................................................................................ -

Thomas Goldthwaite

Goldthwaite Genealogy ---=---.::c==-=-: ==================== DESCENDANTS OF THOMAS GOLDTHWAITE AN EARLY SETTLER Of SALEM, MASS. \\'!Tll SOME ACCOUNT OF T!IE GOLDTHWAITE FAMILY IN ENGLAND Jj'llttlltrntrl.J COMl'ILFn ANIJ l'IJ111.ISl1Fn By CHARLOTTE GOLDTHWAITE Compiler of the Boardmnn li-enenlo~y 11,artforb }l'mili : THE CASE, LoCK\\'OOD & BRAINARD CoMP.\NY 1899 GOLDTHvVAITE GENEALOGY The GOLDTHWAITE GENEALOGY is now ready for delivery, and will be forwarded to subscribers on receipt of the subscription price, $5.oc per copy, with postage (20 cents), if sent hy mail. - - The <~cnealogT treats of the family of Thomas Gold thwaite, an early settler of Salem, Mass., and ancestor of all of this name in America. The following is a list of its contents: IntrOlluction. History of the Work - Wide Distribution of Family-Sources n( Information -- Different Records Exntnined - Correspondence with Descendants-Centers of Familr Residence Visitcd--Rccords Prc~ervc<l in Fainilies -Tradition: Separation of the Trtte from Falsc--Thc 'l'rne Often Corroborated by Conten1pora.ry Records Impnrtant Clue~ to Lines of Descent thus Obtained - Instances G ivcn - Errors in Records Generally Authentic -The name Gold• thwaite- Various Spellings --Different Forms Used in the Fatnily - • Reasons fur and ng-ainst Use of Final i!-Chnnge from Original Form in Many Nan.H'S -Ooldlhwaitc Remains ns u;arliest Found Varic<l Pronunciations - Its Ag-e ancl AdYantnges as a 8urname Lilllits of its llnme during- First Century in New Englnnd-Natnes St1(•cessively Bortle hy First Home-Acknowled~ntents for Assist ance - lllH~trations -Contrih11tio11s towards Pnblicatinn. The (;oldthwaitc Family in England.