Eyeing the Ear: Roland Barthes and the Song Lync Graduate Studies In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

URL 100% (Korea)

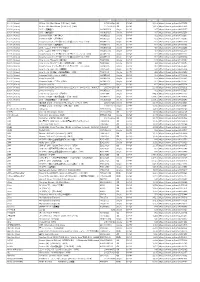

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤C> OKCK5022 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732096 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤B> OKCK5021 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732095 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (チャンヨン)(LTD) OKCK5017 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655033 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤A> OKCK5020 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732093 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ジョンファン)(LTD) OKCK5016 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655032 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ヒョクジン)(LTD) OKCK5018 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655034 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 Single K-POP 421 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 -

The Death Penalty the Seminars of Jacques Derrida Edited by Geoffrey Bennington and Peggy Kamuf the Death Penalty Volume I

the death penalty the seminars of jacques derrida Edited by Geoffrey Bennington and Peggy Kamuf The Death Penalty volume i h Jacques Derrida Edited by Geoffrey Bennington, Marc Crépon, and Thomas Dutoit Translated by Peggy Kamuf The University of Chicago Press ‡ chicago and london jacques derrida (1930–2004) was director of studies at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales, Paris, and professor of humanities at the University of California, Irvine. He is the author of many books published by the University of Chicago Press, most recently, The Beast and the Sovereign Volume I and The Beast and the Sovereign Volume II. peggy kamuf is the Marion Frances Chevalier Professor of French and Comparative Literature at the University of Southern California. She has written, edited, or translated many books, by Derrida and others, and is coeditor of the series of Derrida’s seminars at the University of Chicago Press. Publication of this book has been aided by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2014 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2014. Printed in the United States of America Originally published as Séminaire: La peine de mort, Volume I (1999–2000). © 2012 Éditions Galilée. 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 1 2 3 4 5 isbn- 13: 978- 0- 226- 14432- 0 (cloth) isbn- 13: 978- 0- 226- 09068- 9 (e- book) doi: 10.7208 / chicago / 9780226090689.001.0001 Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Derrida, Jacques, author. -

Cinema 11 Journal of Philosophy and the Moving Image Revista De Filosofia E Da Imagem Em Movimento

CINEMA 11 JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY AND THE MOVING IMAGE REVISTA DE FILOSOFIA E DA IMAGEM EM MOVIMENTO FILM AND ETHICS edited by CINEMA E ÉTICA editado por Patrícia Castello Branco Susana Viegas CINEMA 11 EDITORS Patrícia Silveirinha Castello Branco (IFILNOVA) Sérgio Dias Branco (University of Coimbra/CEIS20) Susana Viegas (IFILNOVA/Deakin University) EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARDD. N. Rodowick (University of Chicago) Francesco Casetti (Catholic University of the Sacred Heart/Yale University) Georges Didi-Huberman (School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences) Ismail Norberto Xavier (University of São Paulo) João Mário Grilo (Nova University of Lisbon/IFILNOVA) Laura U. Marks (Simon Fraser University) Murray Smith (University of Kent) Noël Carroll (City University of New York) Patricia MacCormack (Anglia Ruskin University) Raymond Bellour (New Sorbonne University - Paris 3/CNRS) Stephen Mulhall (University of Oxford) Thomas E. Wartenberg (Mount Holyoke College) INTERVIEWS EDITOR Susana Nascimento Duarte (School of Arts and Design, Caldas da Rainha/IFILNOVA) BOOK REVIEWS EDITOR Maria Irene Aparício (Nova University of Lisbon/IFILNOVA) CONFERENCE REPORTS EDITOR William Brown (University of Roehampton) ISSN 1647-8991 CATALOGS Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) Emerging Sources Citation Index, Clarivate Analytics (ESCI) Web of Science TM European Reference Index for the Humanities and the Social Sciences (ERIH PLUS) Regional Cooperative Online Information System for Scholarly Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal -

©2007 Karey Kar Yee Leung ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

©2007 Karey Kar Yee Leung ALL RIGHTS RESERVED SUSPENSION OF SECULAR SERIOUSNESS: A KIERKEGAARDIAN REVIVAL OF METAPHYSICAL HUMOR IN ETHICO-POLITICAL COMMUNICATION by KAREY KAR YEE LEUNG A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Political Science written under the direction of Drucilla Cornell and approved by ____________________________ ____________________________ ____________________________ ____________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May, 2007 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Suspension of Secular Seriousness: A Kierkegaardian Revival of Metaphysical Humor in Ethico-Political Communication by KAREY KAR YEE LEUNG Dissertation Director: Drucilla Cornell Scientific scholarship when applied to ethics may not only fail in providing a doctrine of ethics, but moreover negatively serve to drain the enthusiasm for concerted action. If a book on ethics makes one complacent rather than agitated to act, then according to Kierkegaard, it is written for unethical purposes. If an individual is more preoccupied with finding the perfect language to speak of ethics than becoming motivated to act in the world, then such profundity becomes a delay tactic to avoid right action. Even the careful attentiveness of waiting to act until one knows for sure that one’s action is the right one becomes a means to uncoil one’s active potential. How then can one write about ethics? Bar remaining silent, perhaps it is not a matter of writing about ethics in a detached manner of scientific academic prose but a way of writing that ignites the passions. Contrary to the common conception that Kierkegaard is against ethics in his pronouncement of Abraham’s “teleological suspension of the ethical” in Fear and Trembling by his pseudonym Johannes de Silentio, I argue that Kierkegaard is deeply invested in exciting his reader towards ethical action even if he writes to offend so that the reader puts the book down in order to live. -

The Essentials of Mysticism

The Essentials of Mysticism Author(s): Underhill, Evelyn (1875-1941) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library i Contents Title Page 1 Preface 2 The Essentials of Mysticism 3 The Mystic and the Corporate Life 18 Mysticism and the Doctrine of Atonement 30 The Mystic As Creative Artist 42 The Education of the Spirit 57 The Place of Will, Intellect and Feeling in Prayer 65 The Mysticism of Plotinus 76 Three Mediæval Mystics 91 1: The Mirror of Simple Souls 92 2: The Blessed Angela of Foligno 104 3: Julian of Norwich 119 Mysticism in Modern France 129 1. Soeur Thérèse de l'Enfant Jésus 130 2. Lucie-Christine 140 3. Charles Péguy 148 Indexes 160 Index of Pages of the Print Edition 161 ii This PDF file is from the Christian Classics Ethereal Library, www.ccel.org. The mission of the CCEL is to make classic Christian books available to the world. • This book is available in PDF, HTML, ePub, and other formats. See http://www.ccel.org/ccel/underhill/essentials.html. • Discuss this book online at http://www.ccel.org/node/7767. The CCEL makes CDs of classic Christian literature available around the world through the Web and through CDs. We have distributed thousands of such CDs free in developing countries. If you are in a developing country and would like to receive a free CD, please send a request by email to [email protected]. The Christian Classics Ethereal Library is a self supporting non-profit organization at Calvin College. If you wish to give of your time or money to support the CCEL, please visit http://www.ccel.org/give. -

Boon-Marcus In-Praise-Of-Copying

In Praise of Copying IN PRAISE OF COPYING Marcus Boon Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts / London, England / 2010 Copyright © 2010 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College Some rights reserved Copyright © 2010 CC Attribution Share Alike Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Boon, Marcus. In praise of copying / Marcus Boon. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-674-04783-9 (alk. paper) 1. Copying. 2. Philosophical anthropology. 3. Mahayana Buddhism— Doctrines. I. Title. BD225.B66 2010 153—dc22 2010005047 Contents Introduction 1 1 What Is a Copy? 12 2 Copia, or, The Abundant Style 41 3 Copying as Transformation 77 4 Copying as Deception 106 5 Montage 142 6 The Mass Production of Copies 176 7 Copying as Appropriation 204 Coda 238 Notes 251 Acknowledgments 277 Index 279 There are many that I know and they know it. They are all of them repeating and I hear it. I love it and I tell it. I love it and now I will write it. This is now a history of my love of it. I hear it and I love it and I write it. They repeat it. They live it and I see it and I hear it. They live it and I hear it and I see it and I love it and now and always I will write it. There are many kinds of men and women and I know it. They repeat it and I hear it and I love it. This is now a history of the way they do it. -

Fordoblelse in K Ierkegaard's Writings By

“Two things at the same time”: fordoblelse in Kierkegaard’s writings by Carolyn J. Mackie Supervisor: Dr. Robert Sweetman Institute for Christian Studies 2014 Mackie, "Two things at the same time":fordoblelse in Kierkegaard's writings, 2 Introduction “The spiritual person is different from us human beings in that he is, if I may put it this way, so solidly built that he can bear a redoubling /Fordoblelseywithin himself. By comparison, we human beings are like a half-timbered structure compared with a foundation wall—so loosely and weakly built that we are unable to bear a redoubling. But the Christianity o f the New Testament relates specifically to a redoubling. ”1 Existence. Faith. Despair. Subjectivity. If asked to choose a set of words that represent the distinctive voice of 19th century Danish writer0 renS Kierkegaard, these are some that might spring to mind. But—redoubling? Scholars and armchair philosophers alike might be forgiven for scratching their heads at the suggestion. “Er... excuse me, what was that? Re-what?” Redoubling—in Danish, fordoblelse—may not be a buzzword in Kierkegaard scholarship, but Kierkegaard himself freighted the term with enormous significance. Published less than six months before his death, the passage quoted above demonstrates the importance redoubling had gained in Kierkegaard’s thought. Marking the distinctions between the Christianity of the New Testament and the Christianity that he saw exemplified in a spiritually pallid Danish Christendom had become, by this time, the focal point of his project. And, as evident from this passage,fordoblelse had become essential to Kierkegaard’s understanding of true Christianity. -

On the Idea of European Islam Voices of Perpetual Modernity

On the Idea of European Islam Voices of Perpetual Modernity By Mohammed Hashas A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy to Political Theory Programme in the Faculty of Political Science, LUISS University of Rome, Italy LUISS Advisors: External Advisor: Professor Sebastiano Maffetone Doctor Jan Jaap de Ruiter Professor Francesca Corrao Tilburg University, the Netherlands March 2013 This page is intentionally left blank ii Abstract This work raises and deals with the following question: is European Islam possible? Following the methodology adopted in studying the selected texts, I argue that it is possible, theologically and politically. To corroborate my argument, I assist myself with three sub-questions that correspond to three cognitive and methodological stages of work. In the descriptive stage, I tackle this question: what is European Islam? I select four projects that advocate what I refer to as the “idea of European Islam.” These projects are advanced by Bassam Tibi, Tariq Ramadan, Tareq Oubrou, and Abdennour Bidar. Despite their differing approaches, I use textual analysis approach in reading the main aspects and concepts of their projects, which I later use for comparative purposes and conceptualization of the idea of European Islam. Subsequently, I enter the comparative stage so as to better understand what European Islam brings new. This stage deals with the following question: what is new in European Islam? Here, I revisit three scholarly generations from the Islamic tradition as a way of finding out what they share, or not, with European Islam. I refer to the Muʻtazila rationalist theological tradition, with major reference to the example of Qadi Abd Aljabbar. -

Workshop on Cosmology and Time

Workshop on Cosmology and Time State College, PA; 16-17 April 2013 Version: 16 April 2013 philsci-archive.pitt.edu Workshop on Cosmology and Time State College, PA; 16-17 April 2013 This conference volume was automatically compiled from a collection of papers deposited in PhilSci-Archive in conjunction with Workshop on Cosmology and Time (State College, PA; 16-17 April 2013). PhilSci-Archive offers a service to those organizing conferences or preparing volumes to allow the deposit of papers as an easy way to circulate advance copies of papers. If you have a conference or volume you would like to make available through PhilSci-Archive, please send an email to the archive’s academic advisors at [email protected]. PhilSci-Archive is a free online repository for preprints in the philosophy of science offered jointly by the Center for Philosophy of Science and the University Library System, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA Compiled on 16 April 2013 This work is freely available online at: http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/view/confandvol/confandvol2013wctstatecollpaapril16172013.html All of the papers contained in this volume are preprints. Cite a preprint in this document as: Author Last, First (year). Title of article. Preprint volume for Workshop on Cosmology and Time, retrieved from PhilSci-Archive at http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/view/confandvol/confandvol2013wctstatecollpaapril16172013.html, Version of 16 April 2013, pages XX - XX. All documents available from PhilSci-Archive may be protected under U.S. and foreign copyright laws, and may not be reproduced without permission. Table of Contents Page Abhay Ashtekar, Response to: Three Merry Roads to T-Violation, by Bryan W. -

Az EXO Nevű Koreai Fiúcsapat Debütkoncepciójának Vallási Szegmensei És Társadalmi Fogadtatása

Hanó Renáta Az EXO nevű koreai fiúcsapat debütkoncepciójának vallási szegmensei és társadalmi fogadtatása Bevezető Napjainkban Dél-Korea egyik legfontosabb kulturális vonzereje a hallyu 한류, amelyet más néven koreai hullámnak nevezünk. A hallyu magába fog- lalja a koreai tradicionális hagyományok, a koreai sorozatok és a koreai zene széleskörű elterjesztését és elterjedését. Dolgozatomban elsősorban a koreai popkultúrával fogok foglalkozni. Az amerikai popkultúrához hasonlóan a tá- vol-kelet is megállás nélkül ontja magából az újabb és újabb csapatokat, akik harcba szállnak egymás ellen a koreai és a külföldi piac megnyerése érdeké- ben. Viszont Amerikával ellentétben itt nem csupán jó marketingfogásról van szó: a hivatalossá váló, vagyis debütáló csapatok több éves gyakornokság után olyan munkára adják a fejüket, amely egyszerre hoz hatalmas sikert és egy- ben mérhetetlen túlhajszolást. A koreai zenei popkultúra, más néven k-pop az 1990-es években kezdett kibontakozni az első k-pop csapat, a Seo Taiji & Boys megalakulásával. 1995-ben jött létre a ma már legsikeresebbnek mond- ható cég, az SM. Entertainment, amely kiképezi, és versenyképes koncepcióval eladja az előadóit. Az elmúlt húsz év alatt a debütáló csapatok száma oly mértékben megnöveke- dett, hogy minden egyes menedzsmentnek erősen kell küzdeni a talpon mara- dásért, ami alól természetesen kivételt képez a három nagy tigrisnek is nevezett cég: az SM. Entertainment, a JYP Entertainment és a YJ Entertainment. Egy csapat eladhatósága nagyban függ a tagok kinézetétől, személyiségétől és tehetségétől, továbbá a legnagyobb löketet a cég adta csapatkoncepció jelenti. Ha egy csapatnak megvan a megfelelő stílusa és témája, azt könnyű eladni és megtartani az imázsát a jövőben is. A megfelelő koncepció kialakításához előbb 116 Hanó Renáta meg kell határozni a célcsoportot, fel kell mérni annak befogadóképességét, komoly társadalomkutatásokat kell végezni. -

The Poetry and Criticism of Hayden Carruth

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1990 Existentialism and New England: The oP etry and Criticism of Hayden Carruth. Anthony Jerome Robbins Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Robbins, Anthony Jerome, "Existentialism and New England: The oeP try and Criticism of Hayden Carruth." (1990). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4949. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4949 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Digital Version of Stationary 1

( Stationary 1) ( Stationary 2 ( Stationary 3 ( Stationary 4 ( Stationary 5 ( Contents) 8 ( My Mother, My Other: Or, Some Sort of Influence Quinn Latimer) 24 ( Cold Afternoons Ivan Argote) 30 ( And Now You See the Light, Man Fayen d’Evie) 36 ( Li Dawei Taocheng Wang) 42 ( The Story of — — Rosemary Heather) 52 ( Transcribing Sound Sean O’Toole) 58 ( O.S Filing System Malak Helmy) 64 ( MERIWETHER/ UTROPRULLIONS OF POPULATIONS/ ABC: PRETROGRELLITOL ROBOTICS/ GESTATIONAL PREVALENCE/ OTROWRELLIGUL Chris Fitzpatrick) 82 ( An Entrance or an Exit Sharon Hayes) 5) 90 ( The Glorious Phoenix Adrian Wong) 104 ( Innocence Yeo Wei Wei) 120 ( The Chalet Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer) 126 ( Outside the World Interior or the Light on the Writing Desk Ho Rui An) 140 ( A Toast Clifford Irving) 144 ( On Isolation and Interstices George Szirtes) 150 ( On Xerox Book Nav Haq and James Langdon) 160 ( Note on Stationary Heman Chong and Christina Li) 164 ( Colophon) (6 ( Quinn Latimer My Mother, My Other: Or, Some Sort of Influence I don’t think my mother would have chosen to return on her intelligence, her seriousness, her ambition, wit, as a stuffed giraffe in the studio of her daughter, but anger, grief, skepticism, mania, ardor. It was a look. she is dead. And while moving through those looks, those books, —Sophie Calle that season, and so many before and since, I began recognizing in the pages of these critical and literary Days push off into nights; your mother clones every women a gravity that my mother had herself gleaned object, every subject. Every sentence—what—leads to and adopted, tried and taken on.