Congdon: “See What Is Coming to Pass and Not Only What Is” 294

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calvin's Doctrine of Prayer: an Examination of Book 3, Chapter 20 of the Institutes of the Christian Religion

21 CALVIN'S DOCTRINE OF PRAYER: AN EXAMINATION OF BOOK 3, CHAPTER 20 OF THE INSTITUTES OF THE CHRISTIAN RELIGION D. B. Garlington Anyone who undertakes an examiriation of Calvin's theology soon discovers that the subject of prayer looms large in his thinking. This is due to the fact that prayer is not simply another of the divisions of theological study; it is, rather, of the essence of Christian existence. Thus, Calvin's consciousness of being a teacher of the church finds frequent expression in his exposition of this doctrine, both systematically in the Institutes! and more fragmentarily in the sermons and commentaries.2 Calvin's estimation of the importance of prayer is best expressed in his own words: "The principal exericse which the children of God have is to pray; for in this way they give a true proof of their faith. "3 Prayer, then, is the distinguishing mark of the believing person, because he instinctively casts his burdens upon the Lord.4 The purpose of this article is to make Calvin's teaching on prayer in book three, chapter 20 of the Institutes as accessible as possible, particularly to those who find the unabridged Institutes to be formidable reading.S I have sought to let Calvin speak for himself with a minimum of comment, since his own words can hardly be improved upon. 1. The Necessity of Prayer In Calvin's discussion of prayer in the Institutes, it is indeed significant that he begins with a transitional statement which looks back to those previous sections of his work concerning Christian soteriology and forms a natural bridge to the subject at hand. -

Cosmos: a Spacetime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based On

Cosmos: A SpaceTime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based on Cosmos: A Personal Voyage by Carl Sagan, Ann Druyan & Steven Soter Directed by Brannon Braga, Bill Pope & Ann Druyan Presented by Neil deGrasse Tyson Composer(s) Alan Silvestri Country of origin United States Original language(s) English No. of episodes 13 (List of episodes) 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way 2 - Some of the Things That Molecules Do 3 - When Knowledge Conquered Fear 4 - A Sky Full of Ghosts 5 - Hiding In The Light 6 - Deeper, Deeper, Deeper Still 7 - The Clean Room 8 - Sisters of the Sun 9 - The Lost Worlds of Planet Earth 10 - The Electric Boy 11 - The Immortals 12 - The World Set Free 13 - Unafraid Of The Dark 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way The cosmos is all there is, or ever was, or ever will be. Come with me. A generation ago, the astronomer Carl Sagan stood here and launched hundreds of millions of us on a great adventure: the exploration of the universe revealed by science. It's time to get going again. We're about to begin a journey that will take us from the infinitesimal to the infinite, from the dawn of time to the distant future. We'll explore galaxies and suns and worlds, surf the gravity waves of space-time, encounter beings that live in fire and ice, explore the planets of stars that never die, discover atoms as massive as suns and universes smaller than atoms. Cosmos is also a story about us. It's the saga of how wandering bands of hunters and gatherers found their way to the stars, one adventure with many heroes. -

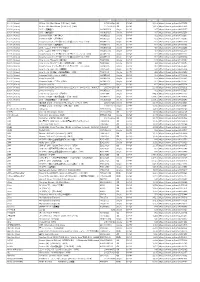

Worldcharts TOP 200 Vom 13.06.2016

CHARTSSERVICE – WORLDCHARTS – TOP 200 NO. 860 – 13.06.2016 PL VW WO PK ARTIST SONG 1 1 6 1 JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE can't stop the feeling! 2 2 7 1 CALVIN HARRIS ft. RIHANNA this is what you came for 3 3 10 1 DRAKE ft. WIZKID & KYLA one dance 4 4 22 1 SIA ft. SEAN PAUL cheap thrills 5 5 24 2 ALAN WALKER faded 6 6 16 3 FIFTH HARMONY ft. TY DOLLA $IGN work from home 7 7 33 4 MIKE POSNER i took a pill in ibiza 8 11 8 8 PINK just like fire 9 15 8 9 KUNGS vs. COOKIN' ON 3 BURNERS this girl 10 9 17 9 CHAINSMOKERS ft. DAYA don't let me down 11 8 34 8 DNCE cake by the ocean 12 17 4 12 DAVID GUETTA ft. ZARA LARSSON this one's for you 13 14 27 7 COLDPLAY ft. BEYONCÉ hymn for the weekend 14 10 36 4 LUKAS GRAHAM 7 years 15 18 10 15 GALANTIS no money 16 12 14 5 MEGHAN TRAINOR no 17 13 30 4 TWENTY ONE PILOTS stressed out 18 16 8 16 ENRIQUE IGLESIAS ft. WISIN duele el corazón 19 26 11 19 ADELE send my love (to your new lover) 20 19 25 7 JONAS BLUE ft. DAKOTA fast car 21 27 5 21 ARIANA GRANDE into you 22 20 20 1 RIHANNA ft. DRAKE work 23 24 11 20 DESIIGNER panda 24 22 31 1 JUSTIN BIEBER love yourself 25 30 15 20 TINIE TEMPAH ft. ZARA LARSSON girls like 26 29 5 26 DRAKE ft. -

URL 100% (Korea)

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤C> OKCK5022 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732096 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤B> OKCK5021 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732095 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (チャンヨン)(LTD) OKCK5017 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655033 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤A> OKCK5020 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732093 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ジョンファン)(LTD) OKCK5016 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655032 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ヒョクジン)(LTD) OKCK5018 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655034 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 Single K-POP 421 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 -

Advent Booklet 2008 for Web Site

PREPARING FOR THE COMING OF JESUS CHRIST ADVENT 2008 DAILY SCRIPTURE READINGS AND REFLECTIONS FROM THE WRITINGS OF JOHN CALVIN Compiled and Edited by Edwin Gray Hurley This Daily Advent Devotional Guide, prepared for South Highland Presbyterian Church of Birmingham, Alabama, contains Daily Scripture Readings from the Common Christian Lec- tionary together with selections from the writings of the renowned Christian Theologian and Reformer John Calvin. 2009 marks the 500TH birthday of Calvin. It will be a year in which we will be invited to delve again into the vast works of this giant of catholic worldwide Christianity, and father of the Reformed and Presbyterian Faith. John Calvin, 1509 – 1564 was born at Noyon in Picardy, France on July 10, 1509, the son of Gerard Cauvin, a man of low birth who rose to become secretary to the bishop and attor- ney to the cathedral chapter. Calvin’s mother, Jeanne le Franc, was the pious daughter of a well-to-do innkeeper of Cambrai. Calvin seemed destined by his father for an ecclesiastical career, and so was sent to study in Paris. There the young stellar student, with a gift for vast memory recall, demonstrated brilliance in philosophical and theological studies. Achieving the masters of arts degree, Calvin’s father turned his obedient son from the study of theol- ogy to that of law in Orleans and later in Bourges. Calvin imbibed the “new learning” of Renaissance ideas that were contesting the supremacy of Medieval Scholasticism. Calvin, who was baptized and raised in the Roman Catholic Church, had a “sudden” con- version to Protestantism, hearing and reading Martin Luther’s fresh teachings, somewhere between 1528 and 1534. -

![2018-2019 ● WCSAB [-] ● RFAB [Allison Kramer] ❖ Campus-Wide Cost of Electricity Is Going up 226% (Not a Typo) Over the Next 5 Years](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2122/2018-2019-wcsab-rfab-allison-kramer-campus-wide-cost-of-electricity-is-going-up-226-not-a-typo-over-the-next-5-years-1252122.webp)

2018-2019 ● WCSAB [-] ● RFAB [Allison Kramer] ❖ Campus-Wide Cost of Electricity Is Going up 226% (Not a Typo) Over the Next 5 Years

REVELLE COLLEGE COUNCIL Thursday, May 3rd, 2018 Meeting #1 I. Call to Order: II. Roll Call PRESENT: Andrej, Hunter, Amanda, Allison, Elizabeth, Art, Eni, Natalie, Isabel, Emily, Blake, Cy’ral, Anna, Samantha, Patrick, ,Dean Sherry, Ivan, Reilly, Neeja, Edward, Patrick, Earnest, Crystal, Garo EXCUSED: Allison, Mick, Miranda, Natalie UNEXCUSED: III. Approval of Minutes IV. Announcements: V. Public Input and Introduction VI. Committee Reports A. Finance Committee [Amanda Jiao] ● I have nothing to report. B. Revelle Organizations Committee [Crystal Sandoval] ● I have nothing to report. C. Rules Committee [Andrej Pervan] ● I have nothing to report. D. Appointments Committee [Hunter Kirby] ● I have nothing to report. E. Graduation Committee [Isabel Lopez] ● I have nothing to report. F. Election Committee [-] G. Student Services Committee [Miranda Pan] ● I have nothing to report. VII. Reports A. President [Andrej Pervan] ● I have nothing to report. B. Vice President of Internal [Hunter Kirby] ● I have nothing to report. C. Vice President of Administration [Elizabeth Bottenberg] ● I have nothing to report. D. Vice President of External [Allison Kramer] ● I have nothing to report. E. Associated Students Revelle College Senators [Art Porter and Eni Ikuku] ● I have nothing to report. F. Director of Spirit and Events [Natalie Davoodi] ● I have nothing to report. G. Director of Student Services [Miranda Pan] ● I have nothing to report. H. Class Representatives ● Fourth Year Representative [Isabel Lopez] ❖ I have nothing to report. ● Third Year Representative [Emily Paris] ❖ I have nothing to report. ● Second Year Representative [Blake Civello] ❖ I have nothing to report. ● First Year Representative [Jaidyn Patricio] ❖ I have nothing to report. I. -

How Chuck Palahniuk's Characters Challenge the Dominant Discourse Jose Antonio Aparicio Florida International University

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 10-28-2008 I want out of the labels : how Chuck Palahniuk's characters challenge the dominant discourse Jose Antonio Aparicio Florida International University DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI14032326 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Aparicio, Jose Antonio, "I want out of the labels : how Chuck Palahniuk's characters challenge the dominant discourse" (2008). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1297. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/1297 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida I WANT OUT OF THE LABELS: HOW CHUCK PALAHNIUK'S CHARACTERS CHALLENGE THE DOMINANT DISCOURSE A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in ENGLISH by Jose Antonio Aparicio 2008 To: Dean Kenneth Furton College of Arts and Sciences This thesis, written by Jose Antonio Aparicio, and entitled, I Want Out of the Labels: How Chuck Palahniuk's Characters Challenge the Dominant Discourse, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved./ Philip Marcus Richard .VSchwartz Ana Luszczyn kV ajor Professor Date of Defense: October 28, 2008 The thesis of Jose Antonio Aparicio is approved. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

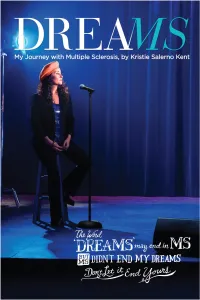

Dreams-041015 1.Pdf

DREAMS My Journey with Multiple Sclerosis By Kristie Salerno Kent DREAMS: MY JOURNEY WITH MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS. Copyright © 2013 by Acorda Therapeutics®, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Author’s Note I always dreamed of a career in the entertainment industry until a multiple sclerosis (MS) diagnosis changed my life. Rather than give up on my dream, following my diagnosis I decided to fight back and follow my passion. Songwriting and performance helped me find the strength to face my challenges and help others understand the impact of MS. “Dreams: My Journey with Multiple Sclerosis,” is an intimate and honest story of how, as people living with MS, we can continue to pursue our passion and use it to overcome denial and find the courage to take action to fight MS. It is also a story of how a serious health challenge does not mean you should let go of your plans for the future. The word 'dreams' may end in ‘MS,’ but MS doesn’t have to end your dreams. It has taken an extraordinary team effort to share my story with you. This book is dedicated to my greatest blessings - my children, Kingston and Giabella. You have filled mommy's heart with so much love, pride and joy and have made my ultimate dream come true! To my husband Michael - thank you for being my umbrella during the rainy days until the sun came out again and we could bask in its glow together. Each end of our rainbow has two pots of gold… our precious son and our beautiful daughter! To my heavenly Father, thank you for the gifts you have blessed me with. -

Online Ajumma: Self-Presentations of Contemporary Elderly Women Via Digital Media in Korea Jungyoun Moon and Crystal Abidin

8 Online ajumma: Self-presentations of contemporary elderly women via digital media in Korea Jungyoun Moon and Crystal Abidin Introduction Ajumma is a pronoun that refers to middle-aged and married women, but it is more likely to be used as a proper noun that only exists and is used as an everyday word in Korea. The cultural implications of being an ajumma cannot be defined in a word and is difficult to translate (Cho Han, 2002), but it can be situated in the Korean cultural and social context. In general, the common elements that consider whether a woman is an ajumma is determined by being a certain age range (mid-30s to early-70s), being married and having children, expressing specific behaviours (loud voices, being meddlesome), and adopting certain aesthetics of self-presentation (permed hair, gaudy fashion style). In most cases, ajumma-rous women are assigned this status primarily based on their outer appearance. These ajumma-rous elements are stereotypical and disdainful but prevalent in Korean society, and ajummas are often portrayed as clichés. This chapter examines the economic and sociocultural history of ajummas, how they are represented in the Korean media and culture, and how they subsequently self-present via new media technologies to create their own forms of expression and creativity. In the mainstream media, ajummas were used to be represented as objects (Chung, 2008). However, they have become subjects of the media, specifically social media, and they now actively participate in creating their own media culture and communities through the usage of smartphones in their everyday practices. -

The Death Penalty the Seminars of Jacques Derrida Edited by Geoffrey Bennington and Peggy Kamuf the Death Penalty Volume I

the death penalty the seminars of jacques derrida Edited by Geoffrey Bennington and Peggy Kamuf The Death Penalty volume i h Jacques Derrida Edited by Geoffrey Bennington, Marc Crépon, and Thomas Dutoit Translated by Peggy Kamuf The University of Chicago Press ‡ chicago and london jacques derrida (1930–2004) was director of studies at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales, Paris, and professor of humanities at the University of California, Irvine. He is the author of many books published by the University of Chicago Press, most recently, The Beast and the Sovereign Volume I and The Beast and the Sovereign Volume II. peggy kamuf is the Marion Frances Chevalier Professor of French and Comparative Literature at the University of Southern California. She has written, edited, or translated many books, by Derrida and others, and is coeditor of the series of Derrida’s seminars at the University of Chicago Press. Publication of this book has been aided by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2014 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2014. Printed in the United States of America Originally published as Séminaire: La peine de mort, Volume I (1999–2000). © 2012 Éditions Galilée. 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 1 2 3 4 5 isbn- 13: 978- 0- 226- 14432- 0 (cloth) isbn- 13: 978- 0- 226- 09068- 9 (e- book) doi: 10.7208 / chicago / 9780226090689.001.0001 Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Derrida, Jacques, author. -

Sumitomo Forestry Group CSR Report 2018 Contents

FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS Sumitomo Forestry Group CSR Report 2018 Contents 2 Message from the President 52 Governance 179 Social Report 53 Corporate Governance 180 Human Rights Initiatives CSR Activity Hightlight 63 Risk Management 184 Health and Safety 4 HIGHLIGHT 01 Adapting to Climate Change 68 Compliance 197 Employment and Human Resources 6 HIGHLIGHT 02 Promoting MOCCA Development (Timber Solutions) Business 73 Business Continuity Management 210 Social Contribution 8 HIGHLIGHT 03 Biodiversity Conservation 76 Sharing, Protection, and Security of Information Acquisition of Quality-Related HIGHLIGHT 04 Responsible Timber Procurement 230 10 Certication Intellectual Property Management 12 HIGHLIGHT 05 Transition to Renewable Power 79 232 Social Data Generation 81 Return to Shareholders and IR Activities 14 HIGHLIGHT 06 Promotion of Work Style Reforms Sumitomo Forestry Group CSR Material Issues 239 Environmental Report 16 84 Contribution Through Our Businesses and Mid-Term CSR Management Plan (FY2017 result) 240 Environmental Management 85 Overall Business and Scope of Impact 251 Responding to Climate Change 18 CSR Management 88 Housing and Construction Business 272 Responding to Waste and Pollution 19 Corporate Philosophy and CSR Management 129 Distribution Business 293 Biodiversity Conservation 23 CSR-related Policies 141 Manufacturing Facilities Stakeholder Engagement 300 Efcient Use of Water Resources 28 150 Forest Management Initiatives to Achieve Sustainable 303 Environmental Related Data 36 Energy Business Development Goals