Boon-Marcus In-Praise-Of-Copying

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Magician by Kate Simon

The Magician By Kate Simon Chapter One “God, I hate Mondays.” Anna ran her fingers through her long auburn hair. She may have gotten Dad’s long chin, button nose and the monster tush, but at least she had his great hair. Thick curls fell softly to her shoulders. Ok, so she had to touch up the few strands of gray, but at the ripe old age of forty-nine, a few strands weren’t too bad. She punched at the keys of her computer, looking for the right file. The new guy was coming, and she couldn’t find the damn client files. New Guy was replacing Fred Sterling, a tubby, nasty little man who rumor had it once pissed off Mother Teresa, not to mention important clients. His two martini lunches were the stuff of legend. That was until Anna discovered the last straw, heavily padded expense accounts. Fred had been submitting three figure lunch tabs from the same Tribecca restaurant for months. Hand written receipts were unusual in this day of computers, but not unheard of. Something still didn’t feel right. She’d pulled several weeks reports. The receipts in question were written by the same hand. They were also sequential. Fred never was the brightest bulb in the box. A quick call to the restaurant confirmed they ran all receipts through the cash register. It was one thing to tick off clients, but stealing money from the boss’s pocket was a mortal The Magician 2 By Kate Simon sin at Barrow. Freddy boy was left to concentrate all his efforts on his martinis, without those pesky clients to get in the way. -

URL 100% (Korea)

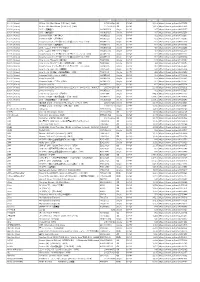

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤C> OKCK5022 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732096 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤B> OKCK5021 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732095 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (チャンヨン)(LTD) OKCK5017 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655033 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤A> OKCK5020 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732093 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ジョンファン)(LTD) OKCK5016 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655032 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ヒョクジン)(LTD) OKCK5018 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655034 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 Single K-POP 421 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 -

Religious Naturalism: the Current Debate

Religious Naturalism: The Current Debate Leidenhag, M. (2018). Religious Naturalism: The Current Debate. Philosophy Compass, 13(8), [e12510]. https://doi.org/10.1111/phc3.12510 Published in: Philosophy Compass Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2018 The Author(s) Philosophy Compass © 2018 John Wiley & Sons Ltd. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:02. Oct. 2021 Religious Naturalism: The Current Debate A religious naturalist seeks to combine two beliefs. The first belief is that nature is all there is. There is no “ontologically distinct and superior realm (such as God, soul, or heaven) to ground, explain, or give meaning to this world” (Stone, 2008, 1). Moreover, the natural sciences are the only or at least most reliable source of knowledge about the world. -

Read This Article (PDF)

Essays in the Philosophy of Humanism Published on behalf of the American Humanist Association and The Institute for Humanist Studies Essays in the Philosophy of Humanism Editor John R. Shook, American Humanist Association Consulting Editor Anthony Pinn, Rice University, USA Editorial Board Louise Antony, University of Massachusetts, USA; Arthur Caplan, New York University, USA; Patricia Churchland, University of California, USA; Franz de Waal, Emory University, USA; Peter Derkx, University of Humanistics, Netherlands; Greg Epstein, Harvard University, USA; Owen Flanagan, Duke University, USA; James Giordano, Georgetown University, USA; Rebecca Goldstein, USA; Anthony Clifford Grayling, New College of the Humanities, United Kingdom; Susan Hansen, University of Pittsburgh, USA; Jennifer Michael Hecht, USA; Marian Hillar, Houston Humanists, USA; Sikivu Hutchinson, Los Angeles County Commission on Human Relations, USA; Philip Kitcher, Columbia University, USA; Stephen Law, University of London, United Kingdom; Cathy Legg, University of Waikato, New Zealand; Jonathan Moreno, University of Pennsylvania, USA; Stephen Pinker, Harvard University, USA; Charlene Haddock Seigfried, Purdue University, USA; Michael Shermer, The Skeptics Society, USA; Alistair J. Sinclair, Centre for Dualist Studies, United Kingdom; Stan van Hooft, Deakin University, Australia; Judy Walker, USA; Sharon Welch, Meadville Theological Seminary, USA Essays in the Philosophy of Humanism publishes scholarly papers concerning philosophical, historical, or interdisciplinary aspects of humanism, or that deal with the application of humanist principles to problems of everyday life. EPH encourages the exploration of aspects and applications of humanism, in the broadest sense of “philosophical” as a search for self-understanding, life wisdom, and improvement to the human condition. The topic of humanism is also understood to embrace its thoughtful manifestations across the widest breadth of cultures and historical periods, and non-western perspectives are encouraged. -

Religion-And-The-Challenges.Pdf

RELIGION AND THE CHALLENGES OF SCIENCE Does science pose a challenge to religion and religious belief? This question has been a matter of long•standing debate • and it continues to concern not only scholars in philosophy, theology, and the sciences, but also those involved in public educational policy. This volume provides background to the current ‘science and religion’ debate, yet focuses as well on themes where recent discussion of the relation between science and religion has been particularly concentrated. The first theme deals with the history of the interrelation of science and religion. The second and third themes deal with the implications of recent work in cosmology, biology and so•called intelligent design for religion and religious belief. The fourth theme is concerned with ‘conceptual issues’ underlying, or implied, in the current debates, such as: Are scientific naturalism and religion compatible? Are science and religion bodies of knowledge or practices or both? Do religion and science offer conflicting truth claims? By illuminating contemporary discussion in the science•religion debate and by outlining the options available in describing the relation between the two, this volume will be of interest to scholars and to members of the educated public alike. This page intentionally left blank Religion and the Challenges of Science Edited by WILLIAM SWEET St Francis Xavier University, Canada and RICHARD FEIST Saint Paul University, Canada © William Sweet and Richard Feist 2007 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. -

Religious Naturalism

Religious Naturalism Michael BarreƩ wonders whether religious naturalism might be ‘a beƩer mouse- trap’. What does ‘religious naturalism’ Rather than trace the burgeoning of modern religious naturalism all through the enlightenment mean? era, it is more useful to focus on the development of this way of thinking in late 19th and early 20th The nineteenth century American thinker Emerson, century USA and Britain. Around that time seen by some as a precursor of modern religious religious naturalism diverged down two parallel naturalism, wrote: ‘If a man builds a better mouse- paths: a non-theistic mainstream approach, trap, the world will beat a path to his door.’ expressed for example by agnostic pragmatist However, if religious naturalism is an example, as I George Santayana, and a theistic approach in which, suggest, of his ‘better mousetrap’, why aren’t more as suggested earlier, Emerson is often cited as an people beating a path to that door? Why isn’t important influence. Some of Emerson’s religious naturalism more widely known? transcendentalist ideas, such as his notion of a ‘universal soul’ within or behind life, would today The term ‘religious’ is used here not to refer to a rule him out as a mainstream religious naturalist. cultural system or to any particular faith or philosophy, but to suggest the kind of affective In the mid-20th century modern religious experience – emotional or ‘spiritual’ feeling – of naturalism flourished among thinkers in the United awe, wonder, at-one-ness, respect, and reverence, States. Henry Nelson Wieman, professor of which can be evoked by nature. philosophy of religion at Chicago University in the 1930s-40s, adopted what he called ‘a theistic stance, ‘Naturalism’ is a view of the world and man’s but without a supernatural God’. -

Vicarious Lulu5 FINALEST VAN NIEUWE DEFINITIVE2 Allerbest …

Envoy When in the Spring of 2015 I started on the editing of this book, it was out of dissatisfaction. The definitive book on my life-long Nkoya research (‘Our Drums Are Always On My Mind’, in press (a)) only required some tedious up- dating for which I lacked the inspiration, and my ongoing ‘Sunda’ empirical research on ‘Rethinking Africa’s transcontinental continuities in pre- and pro- tohistory’, recently enriched by a spell of field-work on the Bamileke Plateau, Cameroon, had reached a break-through. The models of transcontinental inter- action which I had hitherto applied, had turned out to need more rethinking than I had bargained for, and the prospects of bringing out the Nkoya or the Sunda book by the end of the year were thwarted. I thought to remedy this unpleasant situation by quickly compiling a book of my many articles on inter- cultural philosophy. Most of these had already been published and therefore could be expected to be in an accomplished state of textual editing. But I had totally misjudged, both the amount of work involved (given my current stan- dards of perfection), and the centrality this new project was to occupy within the entire scope of my intellectual production. Only gradually did I come to realise what I was really doing: writing my philosophical and Africanist testa- ment, by bringing to bear, upon the original arguments conceived for a phi- losophical audience, the full extent of my comparative empirical research over the last two decades. In this way, what emerged was increasingly a coherent statement on empirically-grounded intercultural philosophy, greatly inspired and intellectually equipped by my philosophical adventure around the Rotter- dam chair of Foundations of Intercultural Philosophy, yet revisiting and reviv- ing the methods and theories of my original training, research and teaching as an anthropologist. -

The Hamptons Diet

fmatter.qxd 3/16/04 1:30 PM Page iii The Hamptons Diet Lose Weight Quickly and Safely with the Doctor’s Delicious Meal Plans FRED PESCATORE, M.D. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. fmatter.qxd 3/16/04 1:30 PM Page vi fmatter.qxd 3/16/04 1:30 PM Page i The Hamptons Diet fmatter.qxd 3/16/04 1:30 PM Page ii Also by Fred Pescatore, M.D. Feed Your Kids Well Thin For Good The Allergy and Asthma Cure fmatter.qxd 3/16/04 1:30 PM Page iii The Hamptons Diet Lose Weight Quickly and Safely with the Doctor’s Delicious Meal Plans FRED PESCATORE, M.D. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. fmatter.qxd 3/16/04 1:30 PM Page iv Copyright © 2004 by Fred Pescatore. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada Design and production by Navta Associates, Inc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008. -

Aesthetics of Gentrification of Aesthetics Edited by Christoph Lindner and Gerard F

CITIES AND CULTURES Lindner & Sandoval (eds) Aesthetics of Gentrification Edited by Christoph Lindner and Gerard F. Sandoval Aesthetics of Gentrification Seductive Spaces and Exclusive Communities in the Neoliberal City Aesthetics of Gentrification Cities and Cultures Cities and Cultures is an interdisciplinary book series addressing the inter relations between cities and the cultures they produce. The series takes a special interest in the impact of globalization on urban space and cultural production, but remains concerned with all forms of cultural expression and transformation associated with modern and contemporary cities. Series Editor: Christoph Lindner, University College London Advisory Board: Ackbar Abbas, University of California, Irvine Myria Georgiou, London School of Economics and Political Science Derek Gregory, University of British Colombia Mona Harb, American University of Beirut Stephanie Hemelryk Donald, University of Lincoln Shirley Jordan, Queen Mary, University of London Nicole Kalms, Monash University Geofffrey Kantaris, University of Cambrigde Brandi Thompson Summers, University of California, Berkeley Ginette Verstraete, VU University Amsterdam Richard J. Williams, University of Edinburgh Aesthetics of Gentrification Seductive Spaces and Exclusive Communities in the Neoliberal City Edited by Christoph Lindner and Gerard F. Sandoval Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Oliver Wainwright Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Layout: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 203 2 eisbn 978 90 4855 117 0 doi 10.5117/9789463722032 nur 758 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/byncnd/3.0) All authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

The Death Penalty the Seminars of Jacques Derrida Edited by Geoffrey Bennington and Peggy Kamuf the Death Penalty Volume I

the death penalty the seminars of jacques derrida Edited by Geoffrey Bennington and Peggy Kamuf The Death Penalty volume i h Jacques Derrida Edited by Geoffrey Bennington, Marc Crépon, and Thomas Dutoit Translated by Peggy Kamuf The University of Chicago Press ‡ chicago and london jacques derrida (1930–2004) was director of studies at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales, Paris, and professor of humanities at the University of California, Irvine. He is the author of many books published by the University of Chicago Press, most recently, The Beast and the Sovereign Volume I and The Beast and the Sovereign Volume II. peggy kamuf is the Marion Frances Chevalier Professor of French and Comparative Literature at the University of Southern California. She has written, edited, or translated many books, by Derrida and others, and is coeditor of the series of Derrida’s seminars at the University of Chicago Press. Publication of this book has been aided by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2014 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2014. Printed in the United States of America Originally published as Séminaire: La peine de mort, Volume I (1999–2000). © 2012 Éditions Galilée. 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 1 2 3 4 5 isbn- 13: 978- 0- 226- 14432- 0 (cloth) isbn- 13: 978- 0- 226- 09068- 9 (e- book) doi: 10.7208 / chicago / 9780226090689.001.0001 Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Derrida, Jacques, author. -

İçindekiler Tanımlar

Din Vikipedi, özgür ansiklopedi Dîn ile karıştırılmamalıdır. Din, genellikle doğaüstü, kutsal ve ahlakî öğeler taşıyan, çeşitli ayin, uygulama, değer ve kurumlara sahipinançlar ve ibâdetler bütünü. Zaman zaman inanç sözcüğünün yerine kullanıldığı gibi, bazen de inanç sözcüğü din sözcüğünün yerinde kullanılır. Dinler tarihine bakıldığında, farklı kültür, topluluk ve bireylerde din kavramının farklı biçimlere sahip olduğu, dinlerin müntesipleri tarafından her çağda, coğrafya ve kültür değerlerine göre yeniden tasarlandığı görülür. Arapça kökenli bir sözcük olan din sözcüğü, köken itibarıyla "yol, hüküm, mükafat" gibi anlamlara sahiptir. İçindekiler Tanımlar Çeşitli dini semboller, soldan sağa: Dinle İlgili Bazı Konu ve Anlayışlar 1. sıra: Hristiyanlık, Musevilik, Hinduizm Din ve Bilim 2. sıra: İslam, Budizm, Şintoizm Din, Felsefe ve Metafizik 3. sıra: Sihizm, Bahailik, Jainizm Ezoterizm ve Mistisizm Çeşitli Dünya Dinleri Nüfus Oranları Ayrıca bakınız Dipnotlar Kaynakça Notlar Dış bağlantılar Tanımlar Din kavramı Encyclopedia.com'da şöyle tanımlanır: Çeşitli çağdaş Pagan inanışlarının "Din üyelerine bir bağlılık amacı, bireylerin simgeleri: eylemlerinin kişisel ve sosyal sonuçlarını Slav • Keltik • Cermenik • Letonya yargılayabilecekleri bir davranış kuralları bütünü ve Helenizm • Ermeni • Romen • Kemetizm bireylerin gruplarını ve evreni bağlayabilecekleri Vika • Macar • Litvanya (açıklayabilecekleri) bir düşünce çerçevesi veren bir [1] Estonya • Çerkez • Semitik • Tanrıça düşünce, his ve eylem sistemidir." tapınması Türk Dil Kurumu sözlüğünde: -

Liberty University Mere Christian Theism And

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Liberty University Digital Commons LIBERTY UNIVERSITY MERE CHRISTIAN THEISM AND THE PROBLEM OF EVIL: TOWARD A TRINITARIAN PERICHORETIC THEODICY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF LIBERTY UIVERSITY SCHOOL OF DIVINITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY RONNIE PAUL CAMPBELL JR. LYNCHBURG, VA JUNE 2015 Copyright © 2015 Ronnie P. Campbell Jr. All Rights Reserved ii APPROVAL SHEET MERE CHRISTIAN THEISM AND THE PROBLEM OF EVIL: TOWARD A TRINITARIAN PERICHORETIC THEODICY Ronnie Paul Campbell Jr. Read and approved by: Chairpersons: David J. Baggett Reader: C. Anthony Thornhill Reader: Leo R. Percer Date: 6/29/2015 iii To my dad, Paul Campbell Thank you for first introducing me to Jesus so many years ago. I owe you much gratitude for setting an example of Christ-like service. To my wife, Debbie, and children, Abby, Caedmon, and Caleb It was your kindness, encouragement, and love that gave me great joy and kept me going. You deserve much more than my words could ever express. To my father-in-law, Bob Bragg Though you’ve had your bout with suffering, I will see you again one day, my friend, in the renewed heavens and earth, where we shall experience no more sickness, pain, or sorrow. We will dwell together in that country—Sweet Beulah Land! iv CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................... viii ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................