PDF Printing 600

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Šum#9 Ni Manifest Ali Skupek Vizij Okoli Dileme, Ki Je Bila V Določenem Obdobju Znana Kot Čto Delat?

Šum #9 Exit or Die Koreografija postajati- Kirurginja -truplo Kazimir Kolar Voranc Kumar Skrivni Scarlett Jo- Jeruzalem hansson Le- Miroslav Griško aps to Your Advanced Lips An interview with R. Scott Bakker Persistent Primož Krašovec, Marko Bauer Threats in the Izhod Arts iz filozofije Patrick Steadman Robert Bobnič Šum #9 Exit or Die 987 Partnerji in koproducenti Društvo Galerija BOKS Društvo Igor Zabel drustvoboks. wordpress.com www.igorzabel.org Galerija Kapelica www.kapelica.org Galerija Miklova hiša www.galerija-miklovahisa.si Partnerji in koproducenti Galerija Škuc galerija.skuc-drustvo.si MGLC Mednarodni grafični likovni center www.mglc-lj.si Mestna galerija Ljubljana www.mgml.si/ mestna-galerija-ljubljana PartnerjiŠum in koproducenti #9 MG+MSUM Moderna galerija www.mg-lj.si UGM Umetnostna galerija Maribor www.ugm.si Zavod Celeia Celje Center sodobnih umetnosti www.celeia.info 990 PartnerjiŠum in koproducenti #9 Aksioma www.aksioma.org OSMO/ZA www.osmoza.si Pizzerija Riko Foculus www.riko.si www.foculus.si 991 Šum #9 1003 Kirurginja Kazimir Kolar 1011 Skrivni Jeruzalem miroslav GrišKo 1029 Advanced Persistent Threats in the Arts patricK steadman 1041 Koreografija postajati-truplo: kratka genealogija umirajočega telesa v računalniških igrah voranc Kumar 1073 Scarlett Johansson Leaps to Your Lips An Interview with R. Scott Bakker primož Krašovec, marKo Bauer 1101 Izhod iz filozofije: François Laruelle roBert BoBnič 1121 Points of View: On Photography & Our Fragmented, Transcendental Selves matt colquhoun 1137 Autism Wars: Neurodivergence as Exit Strategy dominic Fox 1151 Kapitalizem in čustva primož Krašovec 1175 On Letting Go arran crawFord 992 Šum #9 Uvodnik Izstop, exit, predstavlja relativno pogosto paradigmo v umetno- sti. -

EIAB MAGAZINE Contributions from the EIAB and the International Sangha · August 2019

EIAB MAGAZINE Contributions from the EIAB and the international Sangha · August 2019 Contents 2 The Path of the Bodhisattva 41 An MBSR Teacher at the EIAB 85 We can take a leaf out of their book 6 Bells 43 The Ten Commandments – when it comes to living generosity newly formulated 86 How the Honey gets to the EIAB 7 Opening Our Hearts by Taking Root In Ourselves 44 Inner Clarity, Inner Peace 88 Amidst the noble sangha: Interviewing Sr. Song Nghiem 16 “From discrimination to 46 Retreat “time limited ordination, inclusiveness” being a novice at EIAB” 90 Love in Action 19 Honoring Our Ancestors 49 No More War 91 Time-limited Novice Program 23 Construction Management and 50 ‘The only thing we really need is 107 In Memoriam Thầy Pháp Lượng Planning for the 2nd + 3rd Stages of your transformation’ the Renovation of the EIAB 54 Impermanence or the Art of Letting 25 Working Meditation on the Go Construction Project for the Ashoka 56 Slow Hiking and Time in Nature (I) Building 58 Slow Hiking and Time in Nature (II) 27 Every Moment is a Temple European Institute of 60 The Path of Meditation 29 Interview with the Dharma Teacher Applied Buddhism gGmbH 73 Singing at the EIAB Annabelle Zinser from Berlin Schaumburgweg 3 | 51545 Waldbröl 75 It’s a Game + 49 (0)2291 9071373 32 Mindfulness in Schools 77 The weight of the air [email protected] | [email protected] 34 Look Deeply! www.eiab.eu 79 The Dharma of youth – Examples 36 20 Years Intersein-Zentrum from the Wake Up generation Editorial: EIAB. -

Contents Transcriptions Romanization Zen 1 Chinese Chán Sanskrit Name 1.1 Periodisation Sanskrit Dhyāna 1.2 Origins and Taoist Influences (C

7/11/2014 Zen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Zen From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Zen is a school of Mahayana Buddhism[note 1] that Zen developed in China during the 6th century as Chán. From China, Zen spread south to Vietnam, northeast to Korea and Chinese name east to Japan.[2] Simplified Chinese 禅 Traditional Chinese 禪 The word Zen is derived from the Japanese pronunciation of the Middle Chinese word 禪 (dʑjen) (pinyin: Chán), which in Transcriptions turn is derived from the Sanskrit word dhyāna,[3] which can Mandarin be approximately translated as "absorption" or "meditative Hanyu Pinyin Chán state".[4] Cantonese Zen emphasizes insight into Buddha-nature and the personal Jyutping Sim4 expression of this insight in daily life, especially for the benefit Middle Chinese [5][6] of others. As such, it de-emphasizes mere knowledge of Middle Chinese dʑjen sutras and doctrine[7][8] and favors direct understanding Vietnamese name through zazen and interaction with an accomplished Vietnamese Thiền teacher.[9] Korean name The teachings of Zen include various sources of Mahāyāna Hangul 선 thought, especially Yogācāra, the Tathāgatagarbha Sutras and Huayan, with their emphasis on Buddha-nature, totality, Hanja 禪 and the Bodhisattva-ideal.[10][11] The Prajñāpāramitā Transcriptions literature[12] and, to a lesser extent, Madhyamaka have also Revised Romanization Seon been influential. Japanese name Kanji 禅 Contents Transcriptions Romanization Zen 1 Chinese Chán Sanskrit name 1.1 Periodisation Sanskrit dhyāna 1.2 Origins and Taoist influences (c. 200- 500) 1.3 Legendary or Proto-Chán - Six Patriarchs (c. 500-600) 1.4 Early Chán - Tang Dynasty (c. -

Mountains Talking Summer 2020 in This Issue

mountains talking Summer 2020 In this issue... When Cold and Heat Visit When Cold and Heat Visit Karin Ryuku Kempe 3 Karin Ryuku Kempe Temple Practice & Covid-19 Guidelines 4 Today is temperate that too is our human condition. And yet, we can’t get weather, but in past weeks we away from dukkha, can’t avoid it. Daily Vigil Practice 4 have been visited by cold and heat, the Colorado spring. And The first step is to just to see that we cannot. Tung- Garden Zazen 5 some of us may have had chills shan challenges us: “Why not go where there is neither or maybe fever. As a com- cold not heat?” To move away, isn’t it our first instinct? Summer Blooms 6 munity, we are visited by an We squirm in the face of discomfort. But is there any- invisible but powerful disease where without cold or heat? No…no. Of course, Tung- To Practice All Good Joel Tagert 8 process, one to which we are shan knows this, knows it in his bones. He is not playing all vulnerable, no one of us ex- with words and he is not misleading us. He is pushing the Water Peggy Metta Sheehan 9 cepted. Staying close to home, question deeper, closer. Where is that place of no cold no we may be visited by the fear of not having enough sup- heat? Can it be anywhere but right here? Untitled Poem Fred Becker 10 plies, perhaps the loss of our work or financial security, or “When it is cold, let the cold kill you. -

The Effect of War on Art: the Work of Mark Rothko Elizabeth Leigh Doland Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 The effect of war on art: the work of Mark Rothko Elizabeth Leigh Doland Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Doland, Elizabeth Leigh, "The effect of war on art: the work of Mark Rothko" (2010). LSU Master's Theses. 2986. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2986 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EFFECT OF WAR ON ART: THE WORK OF MARK ROTHKO A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Arts in The Interdepartmental Program in Liberal Arts by Elizabeth Doland B.A., Louisiana State University, 2007 May 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT…………………………………………………………………iii CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION……………………………………………........1 2 EARLY LIFE……………………………………………………....3 Yale Years……………………………………………………6 Beginning Life as Artist……………………………………...7 Milton Avery…………………………………………………9 3 GREAT DEPRESSION EFFECTS………………………………...13 Artists’ Union………………………………………………...15 The Ten……………………………………………………….17 WPA………………………………………………………….19 -

Read Book the Miracle of Mindfulness: the Classic Guide To

THE MIRACLE OF MINDFULNESS: THE CLASSIC GUIDE TO MEDITATION BY THE WORLDS MOST REVERED MASTER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Thich Nhat Hanh | 160 pages | 07 Feb 2008 | Ebury Publishing | 9781846041068 | English | London, United Kingdom The Miracle of Mindfulness: The Classic Guide to Meditation by the Worlds Most Revered Master PDF Book Books by Thich Nhat Hanh. Translated into English under his supervision by a friend, you can't sever this fro The subtitle is "an introduction to the practice of meditation. A chronology details the important moments in his life, and rare photographs illustrate key moments. You May Also Like. The same with all Eastern paths. Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and is used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies. The third being my rightful? Original Title. Summary : Over the years, Thich Nhat Hanh and his monastic community in Plum Village, have developed more and more ways to integrate mindfulness practices into every aspect of their daily life. Summary : By a renowned Buddhist monk and best-selling author, this guide offers simple daily practices--including mindfulness of breath, mindful walking, deep listening, mindful speech, and more--to help readers discover the happiness and freedom of living in the present moment. It begins where one is, with basically very little knowledge of how to "breathe" and be mindful. If you cannot make your own child happy, how do you expect to be able to make anyone else happy? Friend Reviews. He suggests to Jim he ought to eat the tangerine. -

Explorers China Exploration and Research Society Volume 17 No

A NEWSLETTER TO INFORM AND ACKNOWLEDGE CERS’ FRIENDS AND SUPPORTERS CHINA since 1986 EXPLORERS CHINA EXPLORATION AND RESEARCH SOCIETY VOLUME 17 NO. 2 SUMMER 2015 3 Last of the Pi Yao Minority People 30 Entering The Dinosaur’s Mouth 6 A Tang Dynasty Temple (circa 502 A.D.) 34 CERS in the Field 9 Avalanche! 35 News/Media & Lectures 12 Caught in Kathmandu 36 Thank You 15 Adventure to Dulongjiang Region: An Unspoiled place in Northwest Yunnan CLOCKWISE FROM TOP: 18 Blue Sky, White Peaks and Green Hills CERS and village cavers in Palawan 22 Shake-Down Cruise of HM Explorer 2 of the Philippines. A Yao elder lady. Earthquake news in Kathmandu. 26 Singing the Ocean Blues Suspension bridge across the Dulong Musings on fish and commitment while floating in the Sulu Sea River in Yunnan. CHINA EXPLORATION AND RESEARCH SOCIETY PAGE 1 A NEWSLETTER TO INFORM AND ACKNOWLEDGE CERS' FRIENDS AND SUPPORTERS Founder / President WONG HOW MAN CHINA Directors: BARRY LAM, CERS Chairman Chairman, Quanta Computer, Taiwan EXPLORERS JAMES CHEN CHINA EXPLORATION AND RESEARCH SOCIETY Managing Director, Legacy Advisors Ltd. HUANG ZHENG YU VOLUME 17 NO.2 SUMMER 2015 Entrepreneur CHRISTABEL LEE President’s Message Managing Director, Toppan Vite Limited DAVID MONG isk management is institutionalized into all big Chairman, Shun Hing Education and Charity Fund businesses today, perhaps with exception of rogue traders among leading banks. In life, risk WELLINGTON YEE management extends from practical measures BILLY YUNG to philosophical ones, from having multiple Group Chairman, Shell Electric Holdings Ltd. Ralternatives of partners, insurance and bank accounts, Advisory Council: education and degrees, to Plan Bs & Cs for zillions of CYNTHIA D’ANJOU BROWN activities, to religious options for those who want to Philanthropy Adviser manage their afterlife, just in case there is an afterlife. -

Jy Din Shakya , a Biography

VENERABLE MASTER JY DIN SHAKYA , A BIOGRAPHY FORWARD BY REV . F A DAO SHAKYA , OHY The following story is the translation from the Chinese of a biography of VM Jy Din -- the Master responsible for the establishment of our Zen Buddhist Order of Hsu Yun. The article is straight journalism, perhaps a bit "dry" in comparison to some of the other Zen essays we are accustomed to encountering. The story of the story, however, is one of convergence, patience and luck -- if we consider “luck” to be the melding of opportunity and action. I have long wished to know more information about the founding master of our order and history of the Hsu Yun Temple in Honolulu. Like many of us, I have scoured books and websites galore for the merest mentions or tidbits of facts. Not being even a whit knowledgeable of Chinese language, any documentation in Master Jy Din's native language was beyond my grasp. I read what I could find -- and waited. I knew that some day I would stumble across that which I sought, if only I did not drive myself to distraction desiring it. Late in July of 2005, that which I had sought was unexpectedly delivered to me. By chance and good fortune, I received an e-mail from Barry Tse, in Singapore -- the continuance of a discussion we had originated on an internet "chat board." As the e-mail discussion continued, Barry mentioned an article he had found on a Chinese Buddhist website -- a biography of our direct Master Jy Din. He pointed out the website to me and I printed a copy of the article for my files. -

道不盡的思念 Endless Thoughts 沴

【海外來鴻】〈憶故人〉 道不盡的思念 Endless Thoughts 沴 by Lily Chang Angel Teng 南非 張莉華 撰文 鄧凱倢 英譯 編按雁本文為凱鴻之母親寫於凱鴻歸空三週年紀念日阻中文稿已刊登於2隹钃期阻歡 迎讀者前賢參閱阻今特刊登英文版(分兩次關以服務廣大英文讀者群阡 馞鶉上期馥馞To be continued 馥 Yuang Chia, as well as uncles and aun- ties from Buddha's Light Association 溫馨盛情的送別 heard of your accident, they have all The Sweet Farewell rushed their way to come pay their When we have finally found you homage to you. You were so fortunate after your accident, the Tzu Chi mem- that Venerable Hui Li had conducted bers have first volunteered to arrange the memorial service for you. Venerable your shrine at our house. They have Hui Li, is the South Africa Buddha's brought fresh flowers, fruits and things Light Association's first abbot (Fo for the setup. Later many more friends Guang Shan, Nan Hua Temple), he has from Tzu Chi, Buddha's Light dedicated his life to toil in propagating Association and I-Kuan Tao had came Buddhism in Africa, highly respected as to recite the holy scriptures for you. a Buddhism Venerable and loved by When Venerable Hui Fang, Venerable Africa people. 38 基礎雜誌胡臑9期 In order to recite “ The True Sutra in Taiwan. Transmit teachers, temple of Mi-Lei Buddha” perfectly in your owners, as well as Tao members from funeral, the I-Kuan Tao members had groups of Chi-Chu, Fa-Yi, Bao-kuang, countless rehearsals before the memori- Tian-Jen, and family friends have come al service. The youth Tao members, from all corners of Taiwan (Taipei, whom were responsible to guard your Taichung, Chiayi & Kaohsiung), they coffin on your day of service, had prac- have waited for your arrival at the ticed through out the nights too. -

URL 100% (Korea)

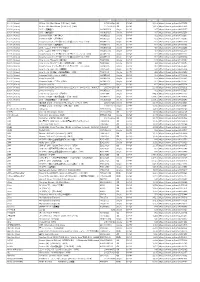

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤C> OKCK5022 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732096 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤B> OKCK5021 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732095 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (チャンヨン)(LTD) OKCK5017 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655033 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤A> OKCK5020 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732093 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ジョンファン)(LTD) OKCK5016 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655032 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ヒョクジン)(LTD) OKCK5018 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655034 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 Single K-POP 421 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 -

Encyclopedia of Buddhism

Encyclopedia of Buddhism J: AF Encyclopedia of Buddhism Encyclopedia of Catholicism Encyclopedia of Hinduism Encyclopedia of Islam Encyclopedia of Judaism Encyclopedia of Protestantism Encyclopedia of World Religions nnnnnnnnnnn Encyclopedia of Buddhism J: AF Edward A. Irons J. Gordon Melton, Series Editor Encyclopedia of Buddhism Copyright © 2008 by Edward A. Irons All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the pub- lisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. An imprint of Infobase Publishing 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Irons, Edward A. Encyclopedia of Buddhism / Edward A. Irons. p. cm. — (Encyclopedia of world religions) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8160-5459-6 (alk. paper) 1. Buddhism—Encyclopedias. I. Title. BQ128.I76 2007 294.303—dc22 2007004503 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quanti- ties for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Spe- cial Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Erika Arroyo Cover design by Cathy Rincon Maps by Dale Williams Printed in the United States of America VB FOF 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper and contains 30% post-consumer recycled content. -

Torturing the Artist: Celebrity and Trope in Media Representations of the Abstract Expressionists

1 Torturing the Artist: Celebrity and Trope in Media Representations of the Abstract Expressionists A Senior Honors Thesis in the Department of Art and Art History By Phoebe Cavise Under the advisement of Professor Eric Rosenberg Professor Malcolm Turvey 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………………………... 3 Introduction About the Paper ……………………………………………………………… 5 Definitions …………………………………………………………………… 8 Celebrity, Suicide, and Celebrity Suicides ………………………………….. 11 About the Process …………………………………………………………… 19 Chapter I. Pollock: Life, Death, and Everything In Between …………………………... 23 Chapter II. Pollock Background …………………………………………………………………. 44 Biopic: Portrait of a Genre ………………………………………………….. 49 Media within Media ………………………………………………………… 53 The Tools of Torture ………………………………………………………... 74 Chapter III. Rothko: Life, Death, and Everything After ……………………………….. 81 Chapter IV. Red Background …………………………………………………………………. 88 Reality and Red ……………………………………………………………... 91 Misery’s Company ………………………………………………………… 103 Productions and Press ……………………………………………………… 108 Chapter V. Directing Red ……………………………………………………………... 119 Conclusions………………………………………………………………………...….. 130 Bibliography ………………………………………………………………………….. 134 3 Acknowledgments First and foremost, thank you to Professor Eric Rosenberg for his complete faith in me. When I proposed a questionably-relevant thesis topic he accepted it wholeheartedly and has done nothing but encourage me every step of the way, even when many of those steps came later than planned. His enthusiasm was paramount to this paper’s completion. Thank you to Professor Ikumi Kaminishi who has advised the latter half of my college career. I am lucky to have worked with someone so supportive and brilliant, whose challenging Theories and Methods class forced me to become a better art historian. Thank you to Professor Malcolm Turvey for joining this project on a topic only half- related to the field in which he is so respected. I only wish my thesis could have been more relevant to his knowledge and utilized his expertise more.