Thich Nhat Hanh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Šum#9 Ni Manifest Ali Skupek Vizij Okoli Dileme, Ki Je Bila V Določenem Obdobju Znana Kot Čto Delat?

Šum #9 Exit or Die Koreografija postajati- Kirurginja -truplo Kazimir Kolar Voranc Kumar Skrivni Scarlett Jo- Jeruzalem hansson Le- Miroslav Griško aps to Your Advanced Lips An interview with R. Scott Bakker Persistent Primož Krašovec, Marko Bauer Threats in the Izhod Arts iz filozofije Patrick Steadman Robert Bobnič Šum #9 Exit or Die 987 Partnerji in koproducenti Društvo Galerija BOKS Društvo Igor Zabel drustvoboks. wordpress.com www.igorzabel.org Galerija Kapelica www.kapelica.org Galerija Miklova hiša www.galerija-miklovahisa.si Partnerji in koproducenti Galerija Škuc galerija.skuc-drustvo.si MGLC Mednarodni grafični likovni center www.mglc-lj.si Mestna galerija Ljubljana www.mgml.si/ mestna-galerija-ljubljana PartnerjiŠum in koproducenti #9 MG+MSUM Moderna galerija www.mg-lj.si UGM Umetnostna galerija Maribor www.ugm.si Zavod Celeia Celje Center sodobnih umetnosti www.celeia.info 990 PartnerjiŠum in koproducenti #9 Aksioma www.aksioma.org OSMO/ZA www.osmoza.si Pizzerija Riko Foculus www.riko.si www.foculus.si 991 Šum #9 1003 Kirurginja Kazimir Kolar 1011 Skrivni Jeruzalem miroslav GrišKo 1029 Advanced Persistent Threats in the Arts patricK steadman 1041 Koreografija postajati-truplo: kratka genealogija umirajočega telesa v računalniških igrah voranc Kumar 1073 Scarlett Johansson Leaps to Your Lips An Interview with R. Scott Bakker primož Krašovec, marKo Bauer 1101 Izhod iz filozofije: François Laruelle roBert BoBnič 1121 Points of View: On Photography & Our Fragmented, Transcendental Selves matt colquhoun 1137 Autism Wars: Neurodivergence as Exit Strategy dominic Fox 1151 Kapitalizem in čustva primož Krašovec 1175 On Letting Go arran crawFord 992 Šum #9 Uvodnik Izstop, exit, predstavlja relativno pogosto paradigmo v umetno- sti. -

EIAB MAGAZINE Contributions from the EIAB and the International Sangha · August 2019

EIAB MAGAZINE Contributions from the EIAB and the international Sangha · August 2019 Contents 2 The Path of the Bodhisattva 41 An MBSR Teacher at the EIAB 85 We can take a leaf out of their book 6 Bells 43 The Ten Commandments – when it comes to living generosity newly formulated 86 How the Honey gets to the EIAB 7 Opening Our Hearts by Taking Root In Ourselves 44 Inner Clarity, Inner Peace 88 Amidst the noble sangha: Interviewing Sr. Song Nghiem 16 “From discrimination to 46 Retreat “time limited ordination, inclusiveness” being a novice at EIAB” 90 Love in Action 19 Honoring Our Ancestors 49 No More War 91 Time-limited Novice Program 23 Construction Management and 50 ‘The only thing we really need is 107 In Memoriam Thầy Pháp Lượng Planning for the 2nd + 3rd Stages of your transformation’ the Renovation of the EIAB 54 Impermanence or the Art of Letting 25 Working Meditation on the Go Construction Project for the Ashoka 56 Slow Hiking and Time in Nature (I) Building 58 Slow Hiking and Time in Nature (II) 27 Every Moment is a Temple European Institute of 60 The Path of Meditation 29 Interview with the Dharma Teacher Applied Buddhism gGmbH 73 Singing at the EIAB Annabelle Zinser from Berlin Schaumburgweg 3 | 51545 Waldbröl 75 It’s a Game + 49 (0)2291 9071373 32 Mindfulness in Schools 77 The weight of the air [email protected] | [email protected] 34 Look Deeply! www.eiab.eu 79 The Dharma of youth – Examples 36 20 Years Intersein-Zentrum from the Wake Up generation Editorial: EIAB. -

Mountains Talking Summer 2020 in This Issue

mountains talking Summer 2020 In this issue... When Cold and Heat Visit When Cold and Heat Visit Karin Ryuku Kempe 3 Karin Ryuku Kempe Temple Practice & Covid-19 Guidelines 4 Today is temperate that too is our human condition. And yet, we can’t get weather, but in past weeks we away from dukkha, can’t avoid it. Daily Vigil Practice 4 have been visited by cold and heat, the Colorado spring. And The first step is to just to see that we cannot. Tung- Garden Zazen 5 some of us may have had chills shan challenges us: “Why not go where there is neither or maybe fever. As a com- cold not heat?” To move away, isn’t it our first instinct? Summer Blooms 6 munity, we are visited by an We squirm in the face of discomfort. But is there any- invisible but powerful disease where without cold or heat? No…no. Of course, Tung- To Practice All Good Joel Tagert 8 process, one to which we are shan knows this, knows it in his bones. He is not playing all vulnerable, no one of us ex- with words and he is not misleading us. He is pushing the Water Peggy Metta Sheehan 9 cepted. Staying close to home, question deeper, closer. Where is that place of no cold no we may be visited by the fear of not having enough sup- heat? Can it be anywhere but right here? Untitled Poem Fred Becker 10 plies, perhaps the loss of our work or financial security, or “When it is cold, let the cold kill you. -

Read Book the Miracle of Mindfulness: the Classic Guide To

THE MIRACLE OF MINDFULNESS: THE CLASSIC GUIDE TO MEDITATION BY THE WORLDS MOST REVERED MASTER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Thich Nhat Hanh | 160 pages | 07 Feb 2008 | Ebury Publishing | 9781846041068 | English | London, United Kingdom The Miracle of Mindfulness: The Classic Guide to Meditation by the Worlds Most Revered Master PDF Book Books by Thich Nhat Hanh. Translated into English under his supervision by a friend, you can't sever this fro The subtitle is "an introduction to the practice of meditation. A chronology details the important moments in his life, and rare photographs illustrate key moments. You May Also Like. The same with all Eastern paths. Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and is used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies. The third being my rightful? Original Title. Summary : Over the years, Thich Nhat Hanh and his monastic community in Plum Village, have developed more and more ways to integrate mindfulness practices into every aspect of their daily life. Summary : By a renowned Buddhist monk and best-selling author, this guide offers simple daily practices--including mindfulness of breath, mindful walking, deep listening, mindful speech, and more--to help readers discover the happiness and freedom of living in the present moment. It begins where one is, with basically very little knowledge of how to "breathe" and be mindful. If you cannot make your own child happy, how do you expect to be able to make anyone else happy? Friend Reviews. He suggests to Jim he ought to eat the tangerine. -

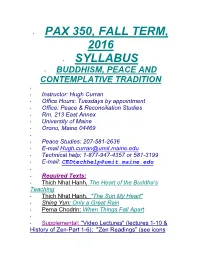

Pax 350, Fall Term, 2016 Syllabus

• PAX 350, FALL TERM, 2016 • SYLLABUS • BUDDHISM, PEACE AND CONTEMPLATIVE TRADITION • • Instructor: Hugh Curran • Office Hours: Tuesdays by appointment • Office: Peace & Reconciliation Studies • Rm. 213 East Annex • University of Maine • Orono, Maine 04469 • • Peace Studies: 207-581-2636 • E-mail [email protected] • Technical help: 1-877-947-4357 or 581-3199 • E-mail: [email protected] • • Required Texts: • Thich Nhat Hanh, The Heart of the Buddha’s Teaching • Thich Nhat Hanh, "The Sun My Heart" • Shing Yun: Only a Great Rain • Pema Chodrin: When Things Fall Apart • • Supplemental: “Video Lectures" (lectures 1-10 & History of Zen-Part 1-6); "Zen Readings” (see icons above lessons): Articles include: The Way of Zen; The Spirit of Zen; Mysticism; Sermons of a Buddhist Abbot ;Dharma Rain; • • Recommended: • Donald Lopez, “The Story of Buddhism” • Dalai Lama: How to Practice Thich Nhat Hanh:"Commentaries on the Heart Sutra" • • The UMA Bookstore 800 number is: 1-800-621- 0083 • The Fax number of the UMA Bookstore is: 1-800- 243-7338The UM Bookstore number is:1-207- 581- 1700 and e-mail at [email protected] • • Course Objective: • Course Objective: • This course is designed as an introduction to Buddhism, especially the practice of Zen (Ch'an). We will examine spiritual & ethical aspects including stories, sutras, ethical precepts, ecological issues, and how we can best embody the Way in our daily lives. • • University Policy: • In complying with the letter and spirit of applicable laws and in pursuing its own goals of pluralism, the University of Maine shall not discriminate on the grounds of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, national origin or citizenship status, age, disability, or veterans status in employment, education, and all other areas of the University. -

Critical Sermons of the Zen Tradition Dr Hisamatsu Shin’Ichi, at Age 87

Critical Sermons of the Zen Tradition Dr Hisamatsu Shin’ichi, at age 87. Photograph taken by the late Professor Hy¯od¯o Sh¯on¯osuke in 1976, at Dr Hisamatsu’s residence in Gifu. Critical Sermons of the Zen Tradition Hisamatsu’s Talks on Linji translated and edited by Christopher Ives and Tokiwa Gishin © Editorial matter and selection © Christopher Ives and Tokiwa Gishin Chapters 1–22 © Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2002 978-0-333-96271-8 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2002 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. -

Intro to Literature & the Environment, Buddhism, Ideology Buddhism And

9/20/2020 Lecture 17: Intro to Literature & the Environment, Buddhism, Ideology - Google Docs Lecture 17: Intro to Literature & the Environment, Buddhism, Ideology Buddhism and Earlier (and Later) Traditions The spiritual context of ancient India had a strong influence on the Buddha’s teachings. Buddhism is made of nonBuddhist elements in the same way that a flower is made of nonflower elements. In the West, Buddhism is often associated with the ideas of reincarnation, karma, and retribution, but these are not originally Buddhist concepts. They were already well established when the Buddha began teaching. In fact, they were not at all at the heart of what the Buddha taught. Thích Nhất Hạnh The idea of reincarnation suggests there is a separate soul, self, or spirit that somehow leaves the body at death, flies away, and then reincarnates in another body. It’s as though the body is some kind of house for the mind, soul, or spirit. This implies that the mind and body can be separated from each other, and that although the body is impermanent, the mind and spirit are somehow permanent. But neither of these ideas is in accord with the deepest teachings of Buddhism. Thích Nhất Hạnh We can speak of two kinds of Buddhism: popular Buddhism and deep Buddhism. Different audiences need different kinds of teachings, so the teachings should always be adapted in order to be appropriate to the audience...In popular Buddhist culture, it is said there are countless hell realms that we can fall into after dying. Many temples display vivid illustrations of what can happen to us in the hell realms—for example, if we lie in this lifetime, our tongue will be cut out in the next. -

Downloads/10YEARSMALL.Pdf

THE NOBLE PATH OF SOCIALLY-ENGAGED PEDAGOGY: CONNECTING TEACHING AND LEARNING WITH PERSONAL AND SOCIETAL WELL-BEING by CLAY McLEOD LL.B., The University of Alberta, 1992 B.Ed., Malaspina University-College, 1999 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN EDUCATION in THE COLLEGE OF GRADUATE STUDIES THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA - OKANAGAN September, 2007 © Clay McLeod, 2007 ii ABSTRACT This thesis is an articulation of how the principles of socially-engaged Buddhism, a spiritual practice rooted in the teachings of the historical Buddha that integrates Buddhist practice and social activism, can enrich and enhance contemporary educational practice. It discusses Buddhist epistemology, metaphysics, ontology, psychology, ethics, and practice and relates these things to holistic education, critical pedagogy, SEL, and global education. On the basis of the theoretical understanding represented by that discussion, it articulates several theoretical principles that can be practically applied to the practice of teaching and learning to make it resonate with the theory and approach of socially- engaged Buddhism. In integrating the implications of Buddhist teachings and practices with teaching and learning practice, it draws from bell hooks’ notion of “engaged pedagogy” in order to articulate a transformational, liberatory, and progressive approach to teaching called “socially-engaged pedagogy.” Socially-engaged pedagogy represents the notion that teaching and learning can be a practical site for progressive social action designed to address the real problem of suffering, both in the present and in the future, as it manifests in the world, exemplified by stress, illness, violence, war, discrimination, oppression, exploitation, poverty, marginalization, and ecological degradation. -

Pulses in the Pattern a Collection Of

PULSES IN THE PATTERN A COLLECTION OF NON-DUAL QUOTATIONS Deepest Thanks To All Who shared These words of wisdom. ………… Thanks to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration - NASA And to the Space Telescope Science Institute - STScI For permission to use the Hubble Telescope Photographs Deep down, Fundamentally, We are the 'Unborn'. We never came into being And We never go out of being. All of these Coming and goings Are just Pulses in the pattern. Bankei The Great Perfection Is Non-conceptual Awareness. Non-conceptual, Ever-fresh, Self-shining Presence awareness. Just this, And Nothing else. Dzogchen teaching Remember, We‟re All In This Alone. Lily Tomlin Enlightenment Is but a recognition, Not a change At all. Helen Schucman From within or From behind, A light shines Through us upon things And makes us aware That we are nothing, But the light is All. R.W. Emerson That which is, Never ceases to be. That which is not, Never comes into being. Parmenides Knowledge - What is to be known - And the knower - These three Do not exist in reality. I am the Spotless Reality In which they appear Because of ignorance. Ashtavakra Gita Peace, be still, and know that I Am God. Peace, be still, and know that I Am. Peace, be still, and know. Peace, be still. Peace, be. Peace. PeacePilgrim, and the Bible This is It And I am It And You are It And so is That And He is It And She is It And It is It And That is That. James Broughton Be yourself. -

Reflections Sutras

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Symposium: EARLY MAHAYANA Mediums and Messages: Reflections on the Production of Mahayana Sutras Paul Harrison 1. Introduction N its discussion of the seventh bhumi or stage on the path leading to the full awakening of a Buddha, the Mahavastu glorifies the manifold qualities of bodhisattvas,I the heroic beings who tread that path. Among their many virtues and achievements, it cites the invention of all the forms of writing known in the world, of which a long list is given.1 This list includes familiar terms like brahmt, kharostri (i.e., kharosthi), Greek (readingyonani with Edgerton for MSS yonari, against Senart’s emendation yavam) and Chinese, as well as * This is a lightly revised version of a paper presented at the symposium “Mahayana Reconsidered: On the Basis of Recent Controversies and Achievements,” convened by Prof. Akira Saito at the 48th International Conference of Eastern Studies of the Tbho Gakkai, Tokyo, 16 May 2003. Earlier drafts were read at Harvard, Stanford (at the Asilomar Conference on early Mahayana in May 2001), Washington and UC Berkeley, and a considerably expanded treatment of the same material was presented as the Radhakrishnan Lectures for 2002 at the University of Oxford. I thank all those colleagues whose comments on these earlier presenta tions have helped me to refine what is still very much a work-in-progress, which I hope will eventually be published in amplified form (vistarena) as a monograph. 1 See Senart 1882, p. 135; translated in Jones 1949, pp. -

Primary Point, Vol 4 Num 3

8 pRIMARypOINT OCTOBER 1987 An account of the "Engaging American Buddhism" ,"MAY OUR BODIES BECOME A retreat and experiment for artists with Thich Nhat ,'. Hanh at the Foundation 1-12 Ojai May moon-so tnoughts arc very simple: heaven ers of the culture." Time after rime as peo is to walk on the earth, horne, just taking ple got up and went to the eenter and either (The follo .....ing account is drawn from a retreat journal kept bJ' Ellen Sidor. one of simple steps, happiness." (Thay) spoke or sang or whatever. I felt chills of more than 60 artists participating ill all unusual and historic ltl-day retreat last May Sitting under the medicine tree, 50 quiet resonance and often eame to tears. at the Ojai Foundation, high up ill the foothills above Santa Barbara ill southern folks. Ike hum. Waiting, not waiting, There are a lot of good hearts here. California.. Special thanks go, to Thay (Vietnamese Zen Master Thich Xhut Hanh) readiness, not even readiness. Just being friendships already underway, a sense of in and his senior assistant Sister Phuong, the Ojai Foundation staff and founder Joan there. No thought of enlightenment or credible leisure to explore whatever is Halifax (a long-time student of Zen Master Seung Sahn), and Marlow Hotchkiss teaching, no teacher, no student. Thay emerginl People's personalities are begin and Cynthia Jurs, coordinators of the retreat. The basic concept for the retreat comes slowly. Goes down to the Dharma ning to emerge. especially through the . flo .....edforth from Thay's idea of artists as 'lineage holden' 'for the culture and that yurt to get a cushion. -

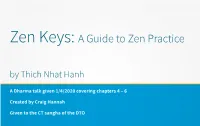

Zen Keys: a Guide to Zen Practice by Thich Nhat Hanh

Zen Keys: A Guide to Zen Practice by Thich Nhat Hanh A Dharma talk given 1/4/2020 covering chapters 4 – 6 Created by Craig Hannah Given to the CT sangha of the DTO Material to be covered Chapter 4 - Mountains Are Mountains and Rivers Are Rivers The Mind Seal True Mind and False Mind Reality in Itself The Lamp and Lampshade A Non-Conceptual Experience The Principle of Non-Duality Interbeing Material to be covered Chapter 5 - Footprints of Emptiness Subject and Object The Birth of Zen Buddhism The Three Gates of Liberation Zen and the West The Eight Negations of Nagarjuna Zen and China The Middle Way The Notion of Emptiness The Vijnanavada School Complementary Notions Classification of the Dharmas Anti-Scholastic Reactions Conscious Knowledge Return to the Source Method of Vijnanavada The A Which Is Not A Is Truly A Alaya as the Basis Penetrating the Tathata The Process of Enlightenment Material to be covered Chapter 6 - The Regeneration of Man Monastic Life The Retreats The Encounter The Role of the Laity The Zen Man and the World of Today Future Perspectives Is an Awakening Possible? Spirituality versus Technology Chapter 4 Mountains Are Mountains and Rivers Are Rivers The Mind Seal ● The Mind Seal is traditionally thought of as “a mind-to-mind recognition between a master and disciple that the disciple has realized the ‘true Dharma eye.’” (e.g. When Buddha holding a flower transmitted it to Mahakashyapa). ● In truth: ● The authentic mind seal is transmitted in every moment. ● It is not transmitted from a master.