Digital Version of Stationary 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In This Issue

BTHINKachelor CRITICALLY • ACT RESPONSIBLY • LEAD EFFECTIVELY • LIVE HUMANELY April 15, 2011 the student voice of wabash since 1908 volume 104 • issue 24 Mockingbird Tan ’14 Debuts at Vanity Wins REED HEPBURN ‘12 STAFF WRITER Baldwin When Harper Lee’s best- selling novel To Kill a Mockinbird was first pub- SEAN HILDEBRAND ‘14 lished in the 1950s, the Ku STAFF WRITER Klux Klan was still rampant in Crawfordsville. This weekend, the stage adapta- Wednesday night’s Baldwin Ora- tion of Mockingbird will torical Contest offered that rare open at Crawfordsville’s opportunity for Wabash students to Vanity Theatre, brought to get paid for the discussions that life by Wabash alum Jim happen on campus all the time. Amidon as director and a Each year, students deliver slew of Wabash personali- speeches to an audience and a dis- ties in the cast. tinguished panel of judges. Those Two Wabash students who placed in the top four earned share a pivotal role in the monetary prizes (1st receives $250, play—freshman Larry 2nd $150, 3rd $100, 4th $50). This Savoy and sophomore is a tradition that dates back to the DeVan Taylor, will alternate beginning years of the school, in weekends to portray Tom 1873, when Judge D.P. Baldwin DREW CASEY | WABASH ‘12 Robinson, the falsely- hosted this event for the first time. Freshman Tim Tan beat two seniors and went on to win this year’s Baldwin Oratorical Contest. Fitting with the accused defendant in a rape Baldwin believed that awards theme of “Practicing Civic Engagement,” Tan spoke on the College’s support (or lack thereof) of GLBT students. -

URL 100% (Korea)

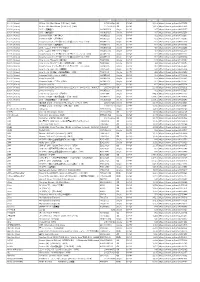

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤C> OKCK5022 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732096 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤B> OKCK5021 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732095 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (チャンヨン)(LTD) OKCK5017 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655033 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤A> OKCK5020 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732093 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ジョンファン)(LTD) OKCK5016 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655032 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ヒョクジン)(LTD) OKCK5018 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655034 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 Single K-POP 421 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 -

Information 2014, 5, 28-100; Doi:10.3390/Info5010028 OPEN ACCESS Information ISSN 2078-2489

Information 2014, 5, 28-100; doi:10.3390/info5010028 OPEN ACCESS information ISSN 2078-2489 www.mdpi.com/journal/information To cite this paper Ghosh, S.; Aswani, K.; Singh, S.; Sahu, S.; Fujita, D.; Bandyopadhyay, A. Design and Construction of a Brain-Like Computer: A New Class of Frequency-Fractal Computing Using Wireless Communication in a Supramolecular Organic, Inorganic System. Information 2014, 5, 28-100. Full paper could be downloaded from journal website free of charge. Article Design and Construction of a Brain-Like Computer: A New Class of Frequency-Fractal Computing Using Wireless Communication in a Supramolecular Organic, Inorganic System Subrata Ghosh, Krishna Aswani, Surabhi Singh, Satyajit Sahu, Daisuke Fujita and Anirban Bandyopadhyay * Advanced Nano Characterization Center, National Institute for Materials Science, 1-2-1 Sengen, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-0047, Japan; E-Mails: [email protected] (S.G.); [email protected] (K.A.); [email protected] (S.Si.); [email protected] (S.Sa.); [email protected] (D.F.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mails: [email protected] or [email protected]. Received: 6 August 2013; in revised form: 8 January 2014 / Accepted: 13 January 2014/ Published: 27 January 2014 Abstract: Here, we introduce a new class of computer which does not use any circuit or logic gate. In fact, no program needs to be written: it learns by itself and writes its own program to solve a problem. Gödel’s incompleteness argument is explored here to devise an engine where an astronomically large number of “if-then” arguments are allowed to grow by self-assembly, based on the basic set of arguments written in the system, thus, we explore the beyond Turing path of computing but following a fundamentally different route adopted in the last half-a-century old non-Turing adventures. -

Rugged Defense Propels BU To

WE’RE THERE WHEN YOU CAN’T BE LADY BEARS from Page 1 TheTUESDAY | MARCH 22, 2011Baylor Lariatwww.baylorlariat.com NEWS Page 3 A&E Page 5 SPORTS Page 6 Row, row, row your boat Album review BU wins one, drops two Anyone can join Baylor crew, but A new worship CD provides Baylor baseball wins a 14-13 the demanding sport requires early an accurate summary of thriller Saturday but loses two of mornings and tough workouts American praise music three games to Texas Tech Vol. 112 No. 31 © 2011, Baylor University In Print >> Keep SXSW global Rugged defense propels BU to win Austin’s raucous South by Southwest fascinates with Lady Bears must Williams wasted no time getting The sophomore was responsible acts from around the world started offensively either, connecting for nine during a 13-2 run that led to on her first jumper and following that Mulkey sitting her starting five and Page 5 rebound to beat up with two layups en route to a 16-0 sending in five reserves to finish out the West Virginia today opening run. game. >> Play outside The Panthers managed their first “No matter what you did at the be- Men’s and women’s track By Matt Larsen points at the 10:56 mark in the first half ginning of the season, no one will re- Sports Writer opens its outdoor season at and finished the half with just eight member,” Pope said when asked about points, the fewest first half points in her energy. “You pretty much remember TCU and performs well A stingy, glamour-less first half de- Women’s NCAA Tournament history. -

Design, Modeling, Fabrication and Characterization of Three-Dimensional Ferromagnetic-Core Solenoid Inductors in Su-8 Interposer

DESIGN, MODELING, FABRICATION AND CHARACTERIZATION OF THREE-DIMENSIONAL FERROMAGNETIC-CORE SOLENOID INDUCTORS IN SU-8 INTERPOSER LAYER FOR EMBEDDED PASSIVE COMPONENT INTEGRATION WITH ACTIVE CHIPS A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By ROBERT CARL FITCH, JR. M.S.E.E., Air Force Institute of Technology, 1990 B.S.E.E., Louisiana Tech University, 1985 B.S.M.E., The Pennsylvania State University, 1983 _______________________________________________________ 2010 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES September 2, 2010 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE DISSERTATION PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Robert Carl Fitch, Jr. ENTITLED Design, Modeling, Fabrication and Characterization of Three-Dimensional Ferromagnetic-Core Solenoid Inductors in SU-8 Interposer Layer for Embedded Passive Component Integration with Active Chips BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy. _________________________________ Marian K. Kazimierczuk, Ph.D. Dissertation Director _________________________________ Ramana V. Grandhi, Ph. D. Director, Ph.D. in Engineering Program _________________________________ Andrew Toming Hsu, Ph.D. Dean, School of Graduate Studies Committee on Final Examination _______________________________________ Antonio Crespo, Ph.D. _______________________________________ Marty Emmert, Ph.D. _______________________________________ Marian Kazimierczuk, Ph.D. _______________________________________ Raymond -

Spartan Daily, March 11, 2015

INSIDE ONLINE: SPARTANDAILY.COM Hi: 68o KILLA WHALE VOCAL LEGENDS MOVEABLE o FEASTS Lo: 47 Andre Nickatina Performers’ ode to plays at The Luther Vandross, Food trucks are Wednesday, Catalyst Chaka Khan and rampant in San Gladys Knight Jose March 11, 2015 PAGE 3 Volume 144 • Issue 20 VISIT SPARTANDAILY.COMANDAILYY.CCOMO Serving San Jose State Universityy sisincence 1934 ANNIVERSARY A CINDERELLA STORY Women’s basketball takes down top seed Bringing up the bottom Two years aft er San Jose’s minimum wage increase, unemployment is down BY ESTEFANY SOSA & MARISSA TRIGOS @estefany_scs @MarissaTrigos Today marks the second anniversary of the Measure D policy that raised the minimum wage in San Jose from $8 an hour to $10 an hour. Th e wage increase, started by Scott Myers-Lipton, San Jose State University Professor of Sociology, and his students, has impacted the lives of many people in the Bay Area. “It does make a diff erence,” said De- varsh Gandhi, international computer engineering graduate student. “If it was eight (dollars an hour) I don’t know what would happen.” Myers-Lipton said Marisela Castro was the student who came up with the idea to increase the minimum wage back in 2010. Myers-Lipton said he still remembers Castro saying, “Profé we have to do this,” when they were covering the section on Photo Contributed by SJSU Athletics minimum wage in his wealth, poverty and privilege class. The San Jose State’s women’s basketball team erupts in excitement after the No.8 seed Spartans’ upset Castro came up with the idea while victory over top-ranked Colorado State during the Mountain West Tournament in Las Vegas yesterday. -

Class of 2021 Triumphs Amid Challenges

Community Graduation Food & Wine Jon M. Chu, film director Read the complete Show some dad-itude with local roots, follows list of local high school with Father’s Day food ‘Crazy’ success with graduates and wine adventures ‘In the Heights’ Page 12 Page 22 Page 29 Vol. 74 No. 23 • 50 cents losaltosonline.com WEDNESDAY • June 9, 2021 Community news for Los Altos, Los Altos Hills and Mountain View since 1947 Class of 2021 triumphs amid challenges Staff turnover By Zoe Morgan Staff Writer/[email protected] debate widens s seniors graduated from Mountain View divide among Aand Los Altos high schools last week, the occasion Hills residents had many of the hallmarks of By Megan V. Winslow a traditional commencement Staff Writer/[email protected] ceremony, from students giving speeches to graduates lining up he volume of emails is over- to receive their diplomas. whelming, missive after for- In other ways, though, the Twarded missive either con- graduations reflected the un- demning or supporting Los Altos precedented year the seniors Hills City Manager Carl Cahill. have experienced, with ceremo- Although residents have debated nies held off-campus to give the rate of town staff turnover for more room for students and months, some as part of an attempt families to social distance. to demonstrate how Cahill’s manage- The celebrations were held at ment style has forced employees to PayPal Park, the soccer stadium leave, the barrage of emails intensi- where the San Jose Earthquakes fied when town planning and build- play. Students and families ing director Zach Dahl sent the city were spread out throughout the council an email explaining his deci- stands. -

Art and Logic of Ramon Llull

The Art and Logic of Ramon Llull BOONER_f1_i-xx.indd i 10/2/2007 1:00:20 PM Studien und Texte zur Geistesgeschichte des Mittelalters Begründet von Josef Koch Weitergeführt von Paul Wilpert, Albert Zimmermann und Jan A. Aertsen Herausgegeben von Andreas Speer In Zusammenarbeit mit Tzotcho Boiadjiev, Kent Emery, Jr. und Wouter Goris BAND XCV BOONER_f1_i-xx.indd ii 10/2/2007 1:00:21 PM The Art and Logic of Ramon Llull A User’s Guide by Anthony Bonner LEIDEN • BOSTON 2007 BOONER_f1_i-xx.indd iii 10/2/2007 1:00:21 PM This book is printed on acid-free paper. A C.I.P. record for this book is available from the Library of Congress ISSN 0169–8028 ISBN 978 90 04 16325 6 © Copyright 2007 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. printed in the netherlands BOONER_f1_i-xx.indd iv 10/5/2007 10:59:30 AM To the memory of Robert Pring-Mill and David Rosenblatt BOONER_f1_i-xx.indd v 10/2/2007 1:00:21 PM BOONER_f1_i-xx.indd vi 10/2/2007 1:00:22 PM CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................ -

Fall 2011 Herald

The erald A Publication of Eastern Christian School Association FALL 2011 VOL. 52 ~ ISSUE 1 H A Celebration of Learning Graduation 2011 2011-2012 ■ Graduation Speeches AnnuAl Also ■ Fund AppeAl Meet the New Principals InsIde: ■ Alumni News and More! see pAge 20 engaging the mind astern Christian School’s mission statement and graduate profile remind us erald that all children are made in the image of God and challenge us “to educate Eeach child to the best of his or her ability and to help each child recognize H the gifts that he / she possesses.” Our goal is that each Eastern Christian graduate will be...”prepared to be a person of Christian vision and influence [who] seeks to contribute ... to God’s mission of renewing all of creation.” This issue of The Herald celebrates learning and the learning community that is Eastern Christian School. It is a celebration of the achievements of our graduates and the learning that has prepared them to continue their education, to enter service on the mission field or in the protection of our country, or to begin full-time employment. It is a celebration of the phenomenal growth in skills, knowledge, and understanding that has enabled our younger students to advance their academic work to the next level. It is a celebration of the learning that has provided our students with a greater understanding of the world around them through problem based learning projects and through concrete efforts to ease suffering throughout the world. It is a celebration of Eastern Christian’s first ever system-wide accreditation and the many months invested in developing Eastern Christian’s Educational Blueprint that will guide our academic endeavors for the next several years. -

The Death Penalty the Seminars of Jacques Derrida Edited by Geoffrey Bennington and Peggy Kamuf the Death Penalty Volume I

the death penalty the seminars of jacques derrida Edited by Geoffrey Bennington and Peggy Kamuf The Death Penalty volume i h Jacques Derrida Edited by Geoffrey Bennington, Marc Crépon, and Thomas Dutoit Translated by Peggy Kamuf The University of Chicago Press ‡ chicago and london jacques derrida (1930–2004) was director of studies at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales, Paris, and professor of humanities at the University of California, Irvine. He is the author of many books published by the University of Chicago Press, most recently, The Beast and the Sovereign Volume I and The Beast and the Sovereign Volume II. peggy kamuf is the Marion Frances Chevalier Professor of French and Comparative Literature at the University of Southern California. She has written, edited, or translated many books, by Derrida and others, and is coeditor of the series of Derrida’s seminars at the University of Chicago Press. Publication of this book has been aided by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2014 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2014. Printed in the United States of America Originally published as Séminaire: La peine de mort, Volume I (1999–2000). © 2012 Éditions Galilée. 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 1 2 3 4 5 isbn- 13: 978- 0- 226- 14432- 0 (cloth) isbn- 13: 978- 0- 226- 09068- 9 (e- book) doi: 10.7208 / chicago / 9780226090689.001.0001 Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Derrida, Jacques, author. -

DOWNLOAD ALBUM INFINITE Top Seed Zip Mp3

DOWNLOAD ALBUM INFINITE Top Seed Zip Mp3 Updated [July 27, 2021}] byBy {MNkba} ~ Users Online: 178 [VERSION 8.32] Newest single from the album is Reminisce (L Solo). Top Seed is the new album by INFINITE. This album has been released on 2018-01-08 and contains 12 tracks. ⇩⇩⇩ CLICK HERE ⇩⇩⇩ DOWNLOAD ALBUM #zippymp3now "Top Seed" track listing: 1. Begin 2. Reminisce (L Solo) 3. Love Song (Sung Jong Solo) 4. Begin Again 5. Tell Me 6. Synchronise 7. No More 8. TGIF (Dong Woo Solo) 9. Pray 10. Why Me 11. Wind 12. I Hate Tags: DOWNLOAD INFINITE - Top Seed Album Leak, [Free ZiP] INFINITE - Top Seed Download MP3, Leak INFINITE - Top Seed album , ( Album ZIP RAR ) INFINITE - Top Seed Album Download, {ZIP & RAR } INFINITE - Top Seed Descargar, [ zip Album ] INFINITE - Top Seed zip free, { Album Download } INFINITE - Top Seed Deluxe Edition, [ZIP] INFINITE Top Seed 320 kbps Album, [Leak..] INFINITE - Top Seed album mp3 telecharger, (2018) Free iTunes INFINITE - Top Seed Deluxe Edition, { Telecharger } INFINITE - Top Seed album télécharger, (Zip Album) INFINITE - Top Seed album mp3 download, ~MP3~ INFINITE - Top Seed Free Download, [Download Free] Album INFINITE - Top Seed Descargar album, {Album 320 kbps} INFINITE - Top Seed (2018) album zip download, { Télécharger } INFINITE - Top Seed (2018) utorrent, [RAR] INFINITE - Top Seed (2018) Album Download, {Album Leak} INFINITE - Top Seed Full Album Download, [ zip Album ] INFINITE - Top Seed 320 kbps Album, { FREE } INFINITE - Top Seed Full Album Télécharger 2018, { ZIP ALBUM } INFINITE - Top Seed Télécharger 2018, (ZiP) INFINITE Top Seed ^ free^, { FREE } INFINITE - Top Seed 320 kbps Album, ^ZIP^ INFINITE - Top Seed Deluxe Edition, [ZIP] INFINITE - Top Seed 2018 download, (FREE) INFINITE - Top Seed Download Free Album, [Full Album} INFINITE - Top Seed (2018) Free iTunes, [Telecharger gratuit] Album INFINITE - Top Seed Album Téléchargment, ^.zip^ .Album. -

ATROPOS PRESS New York • Dresden General Editor: Wolfgang Schirmacher

ATROPOS PRESS new york • dresden General Editor: Wolfgang Schirmacher Editorial Board: Giorgio Agamben Pierre Alferi Hubertus von Amelunxen Alain Badiou Judith Balso Judith Butler Diane Davis Chris Fynsk Martin Hielscher Geert Lovink Larry Rickels Avital Ronell Michael Schmidt Fredrich Ulfers Victor Vitanza Siegfried Zielinski Slavoj Žižek © 2015 by John Calvelli Think Media EGS Series is supported by the European Graduate School Book designed by John Calvelli ATROPOS PRESS New York • Dresden 151 First Avenue # 14, New York, N.Y. 10003 all rights reserved THE FUTURE IS AN IMAGE Unsustainability, Plasticity and the Design of Time John Calvelli For my partner Amery Contents Abbreviations vii INTRODUCTION The Image in Plasticity 1 CHAPTER I Future History 21 CHAPTER II Unsustainability 43 CHAPTER III Designing Time 59 CHAPTER IV The Motor of Plasticity 79 CHAPTER V Plasticity and the Image 105 CHAPTER VI Designing Future 119 Afterword 141 References 143 vii Abbreviations AND And. Phenomenology of the End AOR Acts of religion ATF After the Future CPE For a Critique of a New Political Economy CPR Critique of Pure Reason CPJ Critique of the Power of Judgment CWA The Complete Works of Aristotle DTL Radical Atheism: Derrida and the Time of Life ECN The End of Cheap Nature FOH The Future of Hegel IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change KPM Kant and the Problem of Metaphysics MOP Margins of Philosophy NDP The Neuroplastic Dilemma ODC oxforddictionaries.com OED Online Etymology Dictionary PLH Pierre Loves Horranges Lévinas-Sartre-Nancy TMR Marx’s Theory of Metabolic Rift TT1 Time and Technics 1 TT2 Time and Technics 2 1 Introduction THE IMAGE IN PLASTICITY The Unsustainable Image WE LIVE IN AN UNSUSTAINABLE WORLD .