Performance Philosophy Vol 4(1) (2018): Crisis/Krisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

W2eu Info Guide Greece

WELCOME TO GREECE! D UPDATE N! VERSIO 15 JULY 20 www.w2eu.info AN INFO-GUIDE FOR REFUGEES AND MIGRANTS 2 We are a group of people of whom some live in Greece and some others come from and (usually) live in different Euro - pean countries. We support refugees in the places we live and elsewhere as activists, because for us all human beings are equal. We believe in the freedom of movement as every - body’s right and a world without borders. In order to sup - port you we would like to give you some useful information about your rights in Greece and the overall situation here. We don’t ask for money, we don’t take money and we don’t ask for any reward. We just wish you a safe journey to a bet - ter place and tell you from our side: WELCOME TO EUROPE! If you need any further information not provided in this fly - er or if you have more specialised / personalised questions please ask us directly or contact us via mail: 8 CONTACT @W2EU .INFO W2EU _INFO @YAHOO .COM Last update: July 2015 3 WELCOME TO GREECE! WHAT IS THE CURRENT der for some months now, while SITUATION IN they seemingly continue at the ?THE AEGEAN land border. NEW GOVERNMENT: In February ATTENTION: If you have been 2015 Greece elected a new go - pushed back from Greek territory vernment which is much more (sea or land) to Turkey, specifi - friendly to refugees and migrants cally in the period after February than the governments before. -

Antiquity, Archaeology, and National Imagination in Greece

CLASSICAL PRESENCES General Editors Lorna Hardwick James I. Porter CLASSICAL PRESENCES The texts, ideas, images, and material culture of ancient Greece and Rome have always been crucial to attempts to appropriate the past in order to authenticate the present. They underlie the mapping of change and the assertion and challenging of values and identities, old and new. Classical Presences brings the latest scholarship to bear on the contexts, theory, and practice of such use, and abuse, of the classical past. The Nation and its Ruins: Antiquity, Archaeology, and National Imagination in Greece YANNIS HAMILAKIS 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With oYces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York ß Yannis Hamilakis 2007 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2007 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. -

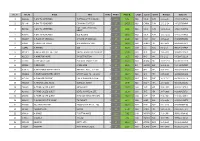

Vol 39 No 48 November 26

Notice of Forfeiture - Domestic Kansas Register 1 State of Kansas 2AMD, LLC, Leawood, KS 2H Properties, LLC, Winfield, KS Secretary of State 2jake’s Jaylin & Jojo, L.L.C., Kansas City, KS 2JCO, LLC, Wichita, KS Notice of Forfeiture 2JFK, LLC, Wichita, KS 2JK, LLC, Overland Park, KS In accordance with Kansas statutes, the following busi- 2M, LLC, Dodge City, KS ness entities organized under the laws of Kansas and the 2nd Chance Lawn and Landscape, LLC, Wichita, KS foreign business entities authorized to do business in 2nd to None, LLC, Wichita, KS 2nd 2 None, LLC, Wichita, KS Kansas were forfeited during the month of October 2020 2shutterbugs, LLC, Frontenac, KS for failure to timely file an annual report and pay the an- 2U Farms, L.L.C., Oberlin, KS nual report fee. 2u4less, LLC, Frontenac, KS Please Note: The following list represents business en- 20 Angel 15, LLC, Westmoreland, KS tities forfeited in October. Any business entity listed may 2000 S 10th St, LLC, Leawood, KS 2007 Golden Tigers, LLC, Wichita, KS have filed for reinstatement and be considered in good 21/127, L.C., Wichita, KS standing. To check the status of a business entity go to the 21st Street Metal Recycling, LLC, Wichita, KS Kansas Business Center’s Business Entity Search Station at 210 Lecato Ventures, LLC, Mullica Hill, NJ https://www.kansas.gov/bess/flow/main?execution=e2s4 2111 Property, L.L.C., Lawrence, KS 21650 S Main, LLC, Colorado Springs, CO (select Business Entity Database) or contact the Business 217 Media, LLC, Hays, KS Services Division at 785-296-4564. -

Hamilakis Nation and Its Ruins.Pdf

CLASSICAL PRESENCES General Editors Lorna Hardwick James I. Porter CLASSICAL PRESENCES The texts, ideas, images, and material culture of ancient Greece and Rome have always been crucial to attempts to appropriate the past in order to authenticate the present. They underlie the mapping of change and the assertion and challenging of values and identities, old and new. Classical Presences brings the latest scholarship to bear on the contexts, theory, and practice of such use, and abuse, of the classical past. The Nation and its Ruins: Antiquity, Archaeology, and National Imagination in Greece YANNIS HAMILAKIS 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With oYces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York ß Yannis Hamilakis 2007 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2007 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. -

Bertus in Stock 7-4-2014

No. # Art.Id Artist Title Units Media Price €. Origin Label Genre Release Eancode 1 G98139 A DAY TO REMEMBER 7-ATTACK OF THE KILLER.. 1 12in 6,72 NLD VIC.R PUN 21-6-2010 0746105057012 2 P10046 A DAY TO REMEMBER COMMON COURTESY 2 LP 24,23 NLD CAROL PUN 13-2-2014 0602537638949 FOR THOSE WHO HAVE 3 E87059 A DAY TO REMEMBER 1 LP 16,92 NLD VIC.R PUN 14-11-2008 0746105033719 HEART 4 K78846 A DAY TO REMEMBER OLD RECORD 1 LP 16,92 NLD VIC.R PUN 31-10-2011 0746105049413 5 M42387 A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS 1 LP 20,23 NLD MOV POP 13-6-2013 8718469532964 6 L49081 A FOREST OF STARS A SHADOWPLAY FOR.. 2 LP 38,68 NLD PROPH HM. 20-7-2012 0884388405011 7 J16442 A FRAMES 333 3 LP 38,73 USA S-S ROC 3-8-2010 9991702074424 8 M41807 A GREAT BIG PILE OF LEAVE YOU'RE ALWAYS ON MY MIND 1 LP 24,06 NLD PHD POP 10-6-2013 0616892111641 9 K81313 A HOPE FOR HOME IN ABSTRACTION 1 LP 18,53 NLD PHD HM. 5-1-2012 0803847111119 10 L77989 A LIFE ONCE LOST ECSTATIC TRANCE -LTD- 1 LP 32,47 NLD SEASO HC. 15-11-2012 0822603124316 11 P33696 A NEW LINE A NEW LINE 2 LP 29,92 EU HOMEA ELE 28-2-2014 5060195515593 12 K09100 A PALE HORSE NAMED DEATH AND HELL WILL.. -LP+CD- 3 LP 30,43 NLD SPV HM. 16-6-2011 0693723093819 13 M32962 A PALE HORSE NAMED DEATH LAY MY SOUL TO. -

What Literature Knows: Forays Into Literary Knowledge Production

Contributions to English 2 Contributions to English and American Literary Studies 2 and American Literary Studies 2 Antje Kley / Kai Merten (eds.) Antje Kley / Kai Merten (eds.) Kai Merten (eds.) Merten Kai / What Literature Knows This volume sheds light on the nexus between knowledge and literature. Arranged What Literature Knows historically, contributions address both popular and canonical English and Antje Kley US-American writing from the early modern period to the present. They focus on how historically specific texts engage with epistemological questions in relation to Forays into Literary Knowledge Production material and social forms as well as representation. The authors discuss literature as a culturally embedded form of knowledge production in its own right, which deploys narrative and poetic means of exploration to establish an independent and sometimes dissident archive. The worlds that imaginary texts project are shown to open up alternative perspectives to be reckoned with in the academic articulation and public discussion of issues in economics and the sciences, identity formation and wellbeing, legal rationale and political decision-making. What Literature Knows The Editors Antje Kley is professor of American Literary Studies at FAU Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany. Her research interests focus on aesthetic forms and cultural functions of narrative, both autobiographical and fictional, in changing media environments between the eighteenth century and the present. Kai Merten is professor of British Literature at the University of Erfurt, Germany. His research focuses on contemporary poetry in English, Romantic culture in Britain as well as on questions of mediality in British literature and Postcolonial Studies. He is also the founder of the Erfurt Network on New Materialism. -

Fleabag’ from London’S West End Expands Distribution in U.S

MEDIA ALERT – September 20, 2019 ‘Fleabag’ from London’s West End Expands Distribution in U.S. Cinemas Monday, November 18 for One Night See the critically acclaimed, award-winning one woman show that inspired the network series with BAFTA winner and Emmy nominee Phoebe Waller-Bridge • WHAT: Fathom Events, BY Experience and National Theatre Live release “Fleabag” in cinemas on Monday, November 18, 2019 at 7:00 p.m. local time, captured live from Wyndham’s Theatre London during its sell out West End run. • WHERE: Tickets for these events can be purchased online by visiting www.FathomEvents.com or at participating theater box offices. Fans throughout the U.S. will be able to enjoy the events in nearly 500 movie theaters through Fathom’s Digital Broadcast Network (DBN). For a complete list of theater locations visit the Fathom Events website (theaters and participants are subject to change). • WHO: Fathom Events, BY Experience and National Theatre Live “Filthy, funny, snarky and touching” Daily Telegraph “Witty, filthy and supreme” The Guardian “Gloriously Disruptive. Phoebe Waller-Bridge is a name to reckon with” The New York Times Fleabag Written by Phoebe Waller-Bridge and directed by Vicky Jones, Fleabag is a rip-roaring look at some sort of woman living her sort of life. Fleabag may appear emotionally unfiltered and oversexed, but that’s just the tip of the iceberg. With family and friendships under strain and a guinea pig café struggling to keep afloat, Fleabag suddenly finds herself with nothing to lose. Fleabag was adapted into a BBC Three Television series in partnership with Amazon Prime Video in 2016 and earned Phoebe a BAFTA Award for Best Female Comedy Performance. -

May 2019 Dear Guests, This Is a Small List of Recommendations and Useful Information for You

www.svacropolis.com Last update: May 2019 Dear Guests, This is a small list of recommendations and useful information for you. It is by no means an exhaustive list as there are too many places to eat, drink and sight-see than we could possibly put down. Rather, this is a list of places that we enjoy and that our guests seem to like. We find that our guests like to discover things themselves. After all, is that not a great part of the joy of traveling? To discover new experiences and places. Just click on the underlined letters (link) to see information concerning whatever you are reading. We wish you a wonderful stay, and we hope you love Athens! Lucy & Andreas ACROPOLIS & OTHER SITES https://etickets.tap.gr/: The official site to purchase tickets online for the Acropolis and slopes, The Temple of Olympian Zeus, Kerameikos, Ancient Agora, Roman Agora, Adrians Library and Aristotle's School. Once you access the site in the left-hand corner there are the letters EΛ|EN; click on the EN for English. MUSEUMS THE ACROPOLIS MUSEUM, Dionysiou Areopagitou 15, Athens 117 42 Summer season hours (1/4 – 31/10) Winter season hours (1/11 – 31/3) Monday 8:00 - 16:00 Monday – Thursday 9:00 - 17:00 Tuesday – Sunday 8:00 – 20:00 Friday 9:00 - 22:00 Friday 8:00 a.m. – 22:00 Saturday – Sunday 9:00 a.m. – 20:00 last admission 30 minutes before closing time Closed: 1 January, Greek Orthodox Easter Sunday, 1 May, 25 and 26 December Good Friday: opens 12:00 to 18:00, Easter Saturday: opens 8:00 to 15:00 On August Full Moon and European Night of Museums, the Museum operates until midnight. -

Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean Culture

ANTONIJE SHKOKLJEV SLAVE NIKOLOVSKI - KATIN PREHISTORY CENTRAL BALKANS CRADLE OF AEGEAN CULTURE Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture By Antonije Shkokljev Slave Nikolovski – Katin Translated from Macedonian to English and edited By Risto Stefov Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2013 by Antonije Shkokljev, Slave Nikolovski – Katin & Risto Stefov e-book edition 2 Index Index........................................................................................................3 COMMON HISTORY AND FUTURE ..................................................5 I - GEOGRAPHICAL CONFIGURATION OF THE BALKANS.........8 II - ARCHAEOLOGICAL DISCOVERIES .........................................10 III - EPISTEMOLOGY OF THE PANNONIAN ONOMASTICS.......11 IV - DEVELOPMENT OF PALEOGRAPHY IN THE BALKANS....33 V – THRACE ........................................................................................37 VI – PREHISTORIC MACEDONIA....................................................41 VII - THESSALY - PREHISTORIC AEOLIA.....................................62 VIII – EPIRUS – PELASGIAN TESPROTIA......................................69 -

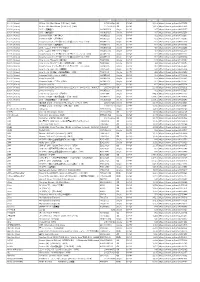

URL 100% (Korea)

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤C> OKCK5022 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732096 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤B> OKCK5021 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732095 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (チャンヨン)(LTD) OKCK5017 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655033 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤A> OKCK5020 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732093 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ジョンファン)(LTD) OKCK5016 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655032 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ヒョクジン)(LTD) OKCK5018 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655034 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 Single K-POP 421 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 -

Writing Figures of Political Resistance for the British Stage Vol1.Pdf

Writing Figures of Political Resistance for the British Stage Volume One (of Two) Matthew John Midgley PhD University of York Theatre, Film and Television September 2015 Writing Figures of Resistance for the British Stage Abstract This thesis explores the process of writing figures of political resistance for the British stage prior to and during the neoliberal era (1980 to the present). The work of established political playwrights is examined in relation to the socio-political context in which it was produced, providing insights into the challenges playwrights have faced in creating characters who effectively resist the status quo. These challenges are contextualised by Britain’s imperial history and the UK’s ongoing participation in newer forms of imperialism, the pressures of neoliberalism on the arts, and widespread political disengagement. These insights inform reflexive analysis of my own playwriting. Chapter One provides an account of the changing strategies and dramaturgy of oppositional playwriting from 1956 to the present, considering the strengths of different approaches to creating figures of political resistance and my response to them. Three models of resistance are considered in Chapter Two: that of the individual, the collective, and documentary resistance. Each model provides a framework through which to analyse figures of resistance in plays and evaluate the strategies of established playwrights in negotiating creative challenges. These models are developed through subsequent chapters focussed upon the subjects tackled in my plays. Chapter Three looks at climate change and plays responding to it in reflecting upon my creative process in The Ends. Chapter Four explores resistance to the Iraq War, my own military experience and the challenge of writing autobiographically. -

Linda by Penelope Skinner and the Wasp by Morgan Lloyd Malcolm Performance Reviews

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 13 | 2016 Thomas Spence and his Legacy: Bicentennial Perspectives Linda by Penelope Skinner and The Wasp by Morgan Lloyd Malcolm Performance reviews William C. Boles Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/9420 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.9420 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference William C. Boles, “Linda by Penelope Skinner and The Wasp by Morgan Lloyd Malcolm ”, Miranda [Online], 13 | 2016, Online since 23 November 2016, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/miranda/9420 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.9420 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Linda by Penelope Skinner and The Wasp by Morgan Lloyd Malcolm 1 Linda by Penelope Skinner and The Wasp by Morgan Lloyd Malcolm Performance reviews William C. Boles Factual information about the shows 1 Play : Linda by Penelope Skinner Place : Royal Court Theatre Downstairs (London) Running time : November, 29th, 2015-January, 9th, 2016 Director : Michael Longhurst Set Designer : Es Devlin Costume Designer : Alex Lowde Lighting Designer : Lee Curran Composer and Sound Designer : Richard Hammarton Video Designer : Luke Halls Movement Director : Imogen Knight Cast : Imogen Byron, Karla Crome, Jaz Deol, NomaDumezweni, Amy Beth Hayes, Dominic Mafham,