The Poetry and Criticism of Hayden Carruth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Vive L'angleterre": Exploring the Relationship Between Britain And

“Vive l’Angleterre” Exploring the Relationship between Britain and Europe in Charlotte Brontë’s Novels Sunniva Sveino Strand A Thesis Presented to The Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages University of Oslo In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the MA Degree Spring 2015 ii “Vive l’Angleterre” Exploring the Relationship between Britain and Europe in Charlotte Brontë’s Novels Sunniva Sveino Strand iii © Sunniva Sveino Strand 2015 “Vive l’Angleterre”: Exploring the Relationship between Britain and Europe in Charlotte Brontë’s Novels Sunniva Sveino Strand http://www.duo.uio.no Print: Reprosentralen, University of Oslo iv Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to explore the complex relationship Charlotte Brontë’s novels have with Europe. It will examine how religion, sexuality and morality, and language are used in order to create a British identity that is contrasted to a European one, but also how these binaries are broken down via the romantic unions of British and European characters and the appeal of certain aspects of Catholicism, European sexuality and the French language. The role of Europe has often been overlooked in favour of the British Empire in Brontë scholarship, and this thesis posits that Europe is integral to the establishment of a British national identity in Brontë’s works. Furthermore, those who have studied the author’s presentation of Europe have often limited themselves to the two novels that are set on the Continent, but I argue that much is lost in disregarding the remainder of Brontë’s works. The findings of this thesis suggest that despite the rampant Europhobia found in Brontë’s works, these novels stand out amongst their contemporaries in envisaging romantic unions between Britons and Europeans and that the British characters need something, or someone, European in order to be fulfilled. -

In This Issue

BTHINKachelor CRITICALLY • ACT RESPONSIBLY • LEAD EFFECTIVELY • LIVE HUMANELY April 15, 2011 the student voice of wabash since 1908 volume 104 • issue 24 Mockingbird Tan ’14 Debuts at Vanity Wins REED HEPBURN ‘12 STAFF WRITER Baldwin When Harper Lee’s best- selling novel To Kill a Mockinbird was first pub- SEAN HILDEBRAND ‘14 lished in the 1950s, the Ku STAFF WRITER Klux Klan was still rampant in Crawfordsville. This weekend, the stage adapta- Wednesday night’s Baldwin Ora- tion of Mockingbird will torical Contest offered that rare open at Crawfordsville’s opportunity for Wabash students to Vanity Theatre, brought to get paid for the discussions that life by Wabash alum Jim happen on campus all the time. Amidon as director and a Each year, students deliver slew of Wabash personali- speeches to an audience and a dis- ties in the cast. tinguished panel of judges. Those Two Wabash students who placed in the top four earned share a pivotal role in the monetary prizes (1st receives $250, play—freshman Larry 2nd $150, 3rd $100, 4th $50). This Savoy and sophomore is a tradition that dates back to the DeVan Taylor, will alternate beginning years of the school, in weekends to portray Tom 1873, when Judge D.P. Baldwin DREW CASEY | WABASH ‘12 Robinson, the falsely- hosted this event for the first time. Freshman Tim Tan beat two seniors and went on to win this year’s Baldwin Oratorical Contest. Fitting with the accused defendant in a rape Baldwin believed that awards theme of “Practicing Civic Engagement,” Tan spoke on the College’s support (or lack thereof) of GLBT students. -

Cosmos: a Spacetime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based On

Cosmos: A SpaceTime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based on Cosmos: A Personal Voyage by Carl Sagan, Ann Druyan & Steven Soter Directed by Brannon Braga, Bill Pope & Ann Druyan Presented by Neil deGrasse Tyson Composer(s) Alan Silvestri Country of origin United States Original language(s) English No. of episodes 13 (List of episodes) 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way 2 - Some of the Things That Molecules Do 3 - When Knowledge Conquered Fear 4 - A Sky Full of Ghosts 5 - Hiding In The Light 6 - Deeper, Deeper, Deeper Still 7 - The Clean Room 8 - Sisters of the Sun 9 - The Lost Worlds of Planet Earth 10 - The Electric Boy 11 - The Immortals 12 - The World Set Free 13 - Unafraid Of The Dark 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way The cosmos is all there is, or ever was, or ever will be. Come with me. A generation ago, the astronomer Carl Sagan stood here and launched hundreds of millions of us on a great adventure: the exploration of the universe revealed by science. It's time to get going again. We're about to begin a journey that will take us from the infinitesimal to the infinite, from the dawn of time to the distant future. We'll explore galaxies and suns and worlds, surf the gravity waves of space-time, encounter beings that live in fire and ice, explore the planets of stars that never die, discover atoms as massive as suns and universes smaller than atoms. Cosmos is also a story about us. It's the saga of how wandering bands of hunters and gatherers found their way to the stars, one adventure with many heroes. -

Anatomy of Criticism, Four Essays

ANATOMY OF CRITICISM Four Essays Anatomy or Criticism FOUR ESSAYS ty NORTHROP FRYE PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS Copyright 1957, by Princeton University Press All Rights Reserved L.C. Card No. 56-8380 ISBN 0-691-01298-9 (paperback edn.) ISBN 0-691-06004-5 (hardcover edn.) Publication of this book has been aided by a grant from the Council of the Humanities, Princeton University, and the Class of 1932 Lectureship. First PRINCETON PAPERBACK Edition, 1971 Third printing, 1973 Tli is book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise disposed of without the pub lisher's consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. Printed in the United States of America by Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey HELENAE UXORI PREFATORY STATEMENTS AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS THIS book forced itself on me while I was trying to write some thing else, and it probably still bears the marks of the reluctance with which a great part of it was composed. After completing a of William Blake study (Fearful Symmetry, 1947), I determined to the of apply principles literary symbolism and Biblical typology which I had learned from Blake to another poet, preferably one who had taken these principles from the critical theories of his own day, instead of working them out by himself as Blake did. I therefore a began study of Spenser's Faerie Queene, only to dis cover that in my beginning was my end. The introduction to an Spenser became introduction to the theory of allegory, and that theory obstinately adhered to a much larger theoretical structure. -

A MEDIUM for MODERNISM: BRITISH POETRY and AMERICAN AUDIENCES April 1997-August 1997

A MEDIUM FOR MODERNISM: BRITISH POETRY AND AMERICAN AUDIENCES April 1997-August 1997 CASE 1 1. Photograph of Harriet Monroe. 1914. Archival Photographic Files Harriet Monroe (1860-1936) was born in Chicago and pursued a career as a journalist, art critic, and poet. In 1889 she wrote the verse for the opening of the Auditorium Theater, and in 1893 she was commissioned to compose the dedicatory ode for the World’s Columbian Exposition. Monroe’s difficulties finding publishers and readers for her work led her to establish Poetry: A Magazine of Verse to publish and encourage appreciation for the best new writing. 2. Joan Fitzgerald (b. 1930). Bronze head of Ezra Pound. Venice, 1963. On Loan from Richard G. Stern This portrait head was made from life by the American artist Joan Fitzgerald in the winter and spring of 1963. Pound was then living in Venice, where Fitzgerald had moved to take advantage of a foundry which cast her work. Fitzgerald made another, somewhat more abstract, head of Pound, which is in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. Pound preferred this version, now in the collection of Richard G. Stern. Pound’s last years were lived in the political shadows cast by his indictment for treason because of the broadcasts he made from Italy during the war years. Pound was returned to the United States in 1945; he was declared unfit to stand trial on grounds of insanity and confined to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital for thirteen years. Stern’s novel Stitch (1965) contains a fictional account of some of these events. -

The Fragmentation of Imagism It Was 1912, and a New Mode of Poetry Was Taking Root

The Fragmentation of Imagism It was 1912, and a new mode of poetry was taking root. Sparked by the ideas of T.E. Hulme and from distaste of the drippy sentimentalism of the Romantic era (Britannica “Imagist”), Ezra Pound, Richard Aldington, and H.D. literally wrote the rules of Imagism. Their dry, concise look at an image or “complex,” as Pound described it, helped lay the foundation for modernist poetry. However, the Imagists’ granite rules could not ensure strict adherence to their form, not even from founding members of Imagism themselves. As the years went by, the Imagists themselves grew weary of their own form by both their own admittance and through their later works. Ezra Pound was the first leader of the Imagist movement, and his autocratic grip on the concept of Imagism may be partly to blame for the fragmentation of the movement. Pound makes it quite clear that, “At least for myself, I want [twentieth-century poetry] so, austere, direction, free from emotional slither (“A Retrospect” 23).” He carefully selected and edited poems for published volumes of Imagist poetry, but the appearance of the popular and wealthy poet heiress Amy Lowell swept in a new democratic format for the group’s publications. Authors were to select what they considered their best work, without the stamp of approval from Pound deeming it true to the Imagist credo (Bradshaw 159). Amy Lowell and Ezra Pound clashed quite famously over the direction Imagism would take, as seen in Lowell’s poem to Pound, harshly dubbed “Astigmatism.” The poem pulls no punches; the analogy is clear in Lowell’s image of the Poet smashing lovely flowers of all kinds, saying “They are useless. -

First World War Poems Free

FREE FIRST WORLD WAR POEMS PDF Sir Andrew Motion | 192 pages | 07 Oct 2004 | FABER & FABER | 9780571221202 | English | London, United Kingdom First World - Prose & Poetry To commemorate the centennial of World War I, we present a selection of poets who served as soldiers, medical staff, journalists, or volunteers. Some poets glorified the cause patriotically—trumpeting the older, traditional notions of duty and honor, while mourning the millions of dead. Our list—sorted by country, then alphabetically—is not comprehensive, but it serves as a starting point for readers interested in exploring the Great War from many perspectives. We'll be adding more poets to this list periodically. Also be sure to take a First World War Poems at our sampler First World War Poems the Poetry First World War Poems World War I. Prose Home Harriet Blog. Visit Home Events Exhibitions First World War Poems. Newsletter Subscribe Give. Poetry Foundation. Back to Previous. World War I Poets. From Apollinaire to Rilke, and from Brooke to Sassoon: a sampling of war poets. Rainer Maria Rilke. Georg Trakl. Franz Werfel. John McCrae. Robert W. Richard Aldington. Laurence Binyon. Edmund Blunden. Vera Mary Brittain. Rupert Brooke. Margaret Postgate Cole. May Wedderburn Cannan. Ford Madox Ford. Wilfrid Wilson Gibson. Robert Graves. Julian Grenfell. Ivor Gurney. Robert Nichols. Wilfred Owen. Herbert Read. Edgell Rickword. Isaac Rosenberg. Siegfried Sassoon. May Sinclair. Edward Thomas. Arthur Graeme West. Guillaume Apollinaire. Jean Cocteau. Gottfried Benn. Wilhelm Klemm. August Stramm. Francis Ledwidge. Eugenio Montale. Giuseppe Ungaretti. Alexandr Blok. Nikolai Gumilev. Sergei Yesenin. Hugh MacDiarmid. Charles Hamilton Sorley. Hervey Allen. John Peale Bishop. -

URL 100% (Korea)

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤C> OKCK5022 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732096 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤B> OKCK5021 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732095 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (チャンヨン)(LTD) OKCK5017 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655033 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤A> OKCK5020 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732093 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ジョンファン)(LTD) OKCK5016 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655032 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ヒョクジン)(LTD) OKCK5018 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655034 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 Single K-POP 421 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 -

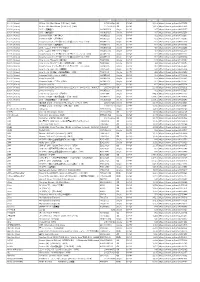

Table of Contents English I-IV

TABLE OF CONTENTS ENGLISH I–IV Literacy From a New Perspective It is important to understand that learning is different in the 21st century than it was in the 20th century. For many of us educated in the 20th century, our learning modalities are closer to Gutenberg than Zuckerberg! Learning changes as technologies change. We’re moving from what would have been a receptive learning ecology to an interactive and productive one. The 21st century is about producing knowledge. It’s a century where students need to develop unique and powerful voices plurally and consider the following questions: How do I speak to different audiences? How do I understand the rhetorical situation? How do I know what my audience needs to hear from me? How do I meet them where they are? There’s not just one generic academic voice; there are multiple voices. It’s also about learning to consider and engage diverse perspectives. —Dr. Ernest Morrell, myPerspectives Texas Author ERNEST MORRELL, Ph.D., Coyle Professor and the Literacy Education Director at the University of Notre Dame 2 Table of Contents myPerspectives Texas provides a rich survey of American, British, and world literature. It ensures that students read and understand a variety of complex texts across multiple genres such as poetry, myths, realistic fiction, historical fiction, speeches, dramas, literary criticism, letters, speeches, articles, short stories, and more. These varied texts allow students to encounter new perspectives, rethink ideas, and deepen their knowledge of contemporary, traditional, and classic literature. STUDENT EDITION THEMATIC UNITS English I. .6 English II . .11 English III. -

Information 2014, 5, 28-100; Doi:10.3390/Info5010028 OPEN ACCESS Information ISSN 2078-2489

Information 2014, 5, 28-100; doi:10.3390/info5010028 OPEN ACCESS information ISSN 2078-2489 www.mdpi.com/journal/information To cite this paper Ghosh, S.; Aswani, K.; Singh, S.; Sahu, S.; Fujita, D.; Bandyopadhyay, A. Design and Construction of a Brain-Like Computer: A New Class of Frequency-Fractal Computing Using Wireless Communication in a Supramolecular Organic, Inorganic System. Information 2014, 5, 28-100. Full paper could be downloaded from journal website free of charge. Article Design and Construction of a Brain-Like Computer: A New Class of Frequency-Fractal Computing Using Wireless Communication in a Supramolecular Organic, Inorganic System Subrata Ghosh, Krishna Aswani, Surabhi Singh, Satyajit Sahu, Daisuke Fujita and Anirban Bandyopadhyay * Advanced Nano Characterization Center, National Institute for Materials Science, 1-2-1 Sengen, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-0047, Japan; E-Mails: [email protected] (S.G.); [email protected] (K.A.); [email protected] (S.Si.); [email protected] (S.Sa.); [email protected] (D.F.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mails: [email protected] or [email protected]. Received: 6 August 2013; in revised form: 8 January 2014 / Accepted: 13 January 2014/ Published: 27 January 2014 Abstract: Here, we introduce a new class of computer which does not use any circuit or logic gate. In fact, no program needs to be written: it learns by itself and writes its own program to solve a problem. Gödel’s incompleteness argument is explored here to devise an engine where an astronomically large number of “if-then” arguments are allowed to grow by self-assembly, based on the basic set of arguments written in the system, thus, we explore the beyond Turing path of computing but following a fundamentally different route adopted in the last half-a-century old non-Turing adventures. -

The Company of Strangers: a Natural History of Economic Life

The Company of Strangers: A Natural History of Economic Life Paul Seabright Contents Page Preface: 2 Part I: Tunnel Vision Chapter 1: Who’s in Charge? 9 Prologue to Part II: 20 Part II: How is Human Cooperation Possible? Chapter 2: Man and the Risks of Nature 22 Chapter 3: Murder, Reciprocity and Trust 34 Chapter 4: Money and human relationships 48 Chapter 5: Honour among Thieves – hoarding and stealing 56 Chapter 6: Professionalism and Fulfilment in Work and War 62 Epilogue to Parts I and II: 71 Prologue to Part III: 74 Part III: Unintended Consequences Chapter 7: The City from Ancient Athens to Modern Manhattan 77 Chapter 8: Water – commodity or social institution? 88 Chapter 9: Prices for Everything? 98 Chapter 10: Families and Firms 110 Chapter 11: Knowledge and Symbolism 126 Chapter 12: Depression and Exclusion 139 Epilogue to Part III: 154 Prologue to Part IV: 155 Part IV: Collective Action Chapter 13: States and Empires 158 Chapter 14: Globalization and Political Action 169 Conclusion: How Fragile is the Great Experiment? 179 The Company of Strangers: A Natural History of Economic Life Preface The Great Experiment Our everyday life is much stranger than we imagine, and rests on fragile foundations. This is the startling message of the evolutionary history of humankind. Our teeming, industrialised, networked existence is not some gradual and inevitable outcome of human development over millions of years. Instead we owe it to an extraordinary experiment launched a mere ten thousand years ago*. No-one could have predicted this experiment from observing the course of our previous evolution, but it would forever change the character of life on our planet. -

Renaissance Texts, Medieval Subjectivities: Vernacular Genealogies of English Petrarchism from Wyatt to Wroth

Renaissance Texts, Medieval Subjectivities: Vernacular Genealogies of English Petrarchism from Wyatt to Wroth by Danila A. Sokolov A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada 2012 © Danila A. Sokolov 2012 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This dissertation investigates the symbolic presence of medieval forms of textual selfhood in early modern English Petrarchan poetry. Seeking to problematize the notion of Petrarchism as a Ren- aissance discourse par excellence, as a radical departure from the medieval past marking the birth of the modern poetic voice, the thesis undertakes a systematic re-reading of a significant body of early modern English Petrarchan texts through the prism of late medieval English poetry. I argue that me- dieval poetic texts inscribe in the vernacular literary imaginary (i.e. a repository of discursive forms and identities available to early modern writers through antecedent and contemporaneous literary ut- terances) a network of recognizable and iterable discursive structures and associated subject posi- tions; and that various linguistic and ideological traces of these medieval discourses and selves can be discovered in early modern English Petrarchism. Methodologically, the dissertation’s engagement with poetic texts across the lines of periodization is at once genealogical and hermeneutic. The prin- cipal objective of the dissertation is to uncover a vernacular history behind the subjects of early mod- ern English Petrarchan poems and sonnet sequences.