Kathavatthu Sutta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ontology of Consciousness

Ontology of Consciousness Percipient Action edited by Helmut Wautischer A Bradford Book The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England ( 2008 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or me- chanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. MIT Press books may be purchased at special quantity discounts for business or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected] or write to Special Sales Depart- ment, The MIT Press, 55 Hayward Street, Cambridge, MA 02142. This book was set in Stone Serif and Stone Sans on 3B2 by Asco Typesetters, Hong Kong, and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ontology of consciousness : percipient action / edited by Helmut Wautischer. p. cm. ‘‘A Bradford book.’’ Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-262-23259-3 (hardcover : alk. paper)—ISBN 978-0-262-73184-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Consciousness. 2. Philosophical anthropology. 3. Culture—Philosophy. 4. Neuropsychology— Philosophy. 5. Mind and body. I. Wautischer, Helmut. B105.C477O58 2008 126—dc22 2006033823 10987654321 Index Abaluya culture (Kenya), 519 as limitation of Turing machines, 362 Abba Macarius of Egypt, 166 as opportunity, 365, 371 Abhidharma in dualism, person as extension of matter, as guides to Buddhist thought and practice, 167, 454 10–13, 58 in focus of attention, 336 basic content, 58 in measurement of intervals, 315 in Asanga’s ‘‘Compendium of Abhidharma’’ in regrouping of elements, 335, 344 (Abhidharma-samuccaya), 67 in technical causality, 169, 177 in Maudgalyayana’s ‘‘On the Origin of shamanic separation from body, 145 Designations’’ Prajnapti–sastra,73 Action, 252–268. -

Chronology of the Pali Canon Bimala Churn Law, Ph.D., M.A., B.L

Chronology of the Pali Canon Bimala Churn Law, Ph.D., M.A., B.L. Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Researchnstitute, Poona, pp.171-201 Rhys Davids in his Buddhist India (p. 188) has given a chronological table of Buddhist literature from the time of the Buddha to the time of Asoka which is as follows:-- 1. The simple statements of Buddhist doctrine now found, in identical words, in paragraphs or verses recurring in all the books. 2. Episodes found, in identical words, in two or more of the existing books. 3. The Silas, the Parayana, the Octades, the Patimokkha. 4. The Digha, Majjhima, Anguttara, and Samyutta Nikayas. 5. The Sutta-Nipata, the Thera-and Theri-Gathas, the Udanas, and the Khuddaka Patha. 6. The Sutta Vibhanga, and Khandhkas. 7. The Jatakas and the Dhammapadas. 8. The Niddesa, the Itivuttakas and the Patisambbhida. 9. The Peta and Vimana-Vatthus, the Apadana, the Cariya-Pitaka, and the Buddha-Vamsa. 10. The Abhidhamma books; the last of which is the Katha-Vatthu, and the earliest probably the Puggala-Pannatti. This chronological table of early Buddhist; literature is too catechetical, too cut and dried, and too general to be accepted in spite of its suggestiveness as a sure guide to determination of the chronology of the Pali canonical texts. The Octades and the Patimokkha are mentioned by Rhys Davids as literary compilations representing the third stage in the order of chronology. The Pali title corresponding to his Octades is Atthakavagga, the Book of Eights. The Book of Eights, as we have it in the Mahaniddesa or in the fourth book of the Suttanipata, is composed of sixteen poetical discourses, only four of which, namely, (1.) Guhatthaka, (2) Dutthatthaka. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 233 3rd International Conference on Contemporary Education, Social Sciences and Humanities (ICCESSH 2018) On a Logical Reconstruction of the Kathavatthu Andrew Schumann University of Information Technology and Management in Rzeszow Rzeszow, Poland E-mail: [email protected] Abstract—The Kathavatthu is one of the treatises of the Formally: Abhidhamma Pitaka of the Pali Canon. This treatise contains many different syllogisms – first of all, modus ponens and (A B) (C D); (C D) modus tollens. It is quite unique, because the same huge —————————————— number of syllogisms involved into reasoning are contained only in the Milindapanha – another treatise of the (A B). Abhidhamma Pitaka. Usually, the authors of the Pali Canon do not appeal to pure syllogisms. In this paper, I show that Another example of correct syllogism as a modification syllogisms play rather a rhetoric role in the Kathavatthu. So, of modus tollens is logically formulated in the Kathāvatthu the author of the Kathavatthu had no excellent competence in as follows: ‗If D be denied of C, then B should have been logic because there are many sophisms among correct denied of A. But you affirmed B of A. Therefore, that B can syllogisms and in the Kathavatthu there is no requirement to be affirmed of A, but not D of C, is wrong,‘ or in the simpler give examples in syllogisms. But the latter requirement is one way: ‗If C is not D, then A is not B. But A is B. Therefore C of the principal ideas of the Indian logic to give examples for is D‘ [3]. -

Sects & Sectarianism

Sects & Sectarianism Also by Bhikkhu Sujato through Santipada A History of Mindfulness How tranquillity worsted insight in the Pali canon Beginnings There comes a time when the world ends… Bhikkhuni Vinaya Studies Research & reflections on monastic discipline for Buddhist nuns A Swift Pair of Messengers Calm and insight in the Buddha’s words Dreams of Bhaddā Sex. Murder. Betrayal. Enlightenment. The story of a Buddhist nun. White Bones Red Rot Black Snakes A Buddhist mythology of the feminine SANTIPADA is a non-profit Buddhist publisher. These and many other works are available in a variety of paper and digital formats. http://santipada.org Sects & Sectarianism The origins of Buddhist schools BHIKKHU SUJATO SANTIPADA SANTIPADA Buddhism as if life matters Originally published by The Corporate Body of the Buddha Education Foundation, Taiwan, 2007. This revised edition published in 2012 by Santipada. Copyright © Bhikkhu Sujato 2007, 2012. Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 2.5 Australia You are free to Share—to copy, distribute and transmit the work under the follow- ing conditions: Attribution. You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). No Derivative Works. You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. With the understanding that: Waiver—Any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder. Other Rights—In no way are any of the following rights affected by the license: o Your fair dealing or fair use rights; o The author’s moral rights; o Rights other persons may have either in the work itself or in how the work is used, such as publicity or privacy rights. -

The Bodhisattva Ideal in Selected Buddhist

i THE BODHISATTVA IDEAL IN SELECTED BUDDHIST SCRIPTURES (ITS THEORETICAL & PRACTICAL EVOLUTION) YUAN Cl Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 2004 ProQuest Number: 10672873 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672873 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This thesis consists of seven chapters. It is designed to survey and analyse the teachings of the Bodhisattva ideal and its gradual development in selected Buddhist scriptures. The main issues relate to the evolution of the teachings of the Bodhisattva ideal. The Bodhisattva doctrine and practice are examined in six major stages. These stages correspond to the scholarly periodisation of Buddhist thought in India, namely (1) the Bodhisattva’s qualities and career in the early scriptures, (2) the debates concerning the Bodhisattva in the early schools, (3) the early Mahayana portrayal of the Bodhisattva and the acceptance of the six perfections, (4) the Bodhisattva doctrine in the earlier prajhaparamita-siltras\ (5) the Bodhisattva practices in the later prajnaparamita texts, and (6) the evolution of the six perfections (paramita) in a wide range of Mahayana texts. -

Sects and Sectarianism: the Origins of Buddhist Schools

Sects & Sectarianism The origins of Buddhist schools Bhikkhu Sujato 2006 This work is copyright©2006BhikkhuSujato.All rights reserved. Permission to reprintmay be obtained on application to the author. Available for free download online at http://sectsandsectarianism.googlepages.com Available for purchase from www.lulu.com. This isat COST PRICE ONLY. Neither the author nor Lulu receives any royalties for purchases. This book must not be sold for profit. Santi ForestMonastery http://santifm1.0.googlepages.com The Sangha of bhikkhus and bhikkhunis has been made unified. As long as my children and grandchildren shall live, and as long as the sun and the moon shall shine, any bhikkhu or bhikkhuni who divides the Sangha shall be made to wear white clothes and dwell outside the monasteries. What it is my wish? That the unity of the Sangha should last a long time. King Aśoka, Minor Pillar Edict, Sāñchī Contents Foreword 1 Abstract 2 1. The ‘Unity Edicts’ 4 2. TheSaintsofVedisa 15 3. The Dīpavaṁsa 24 4. Monster or Saint? 41 5. ThreeSins&FiveTheses 54 6. More on the Vibhajjavādins 79 7. Vibhajjavāda vs. Sarvāstivāda? 89 8. Dharmagupta:TheGreekMissions 98 9. The Mūlasarvāstivādins of Mathura 113 Conclusion 122 Appendix: Chronology 125 Bibliography 128 Mahāsaṅghika Śāriputraparipṛcchā Theravāda Dīpavaṁsa The Mahāsaṅghika school diligently study the collected Suttas and teach the true meaning, because they are the source and the center. They wear These 17 sects are schismatic, yellow robes. only one sect is non-schismatic. The Dharmaguptaka school master With the non-schismatic sect, the flavor ofthe true way.Theyare there areeighteen in all. -

Early Buddhism and Theravāda Buddhism: a Comparative Study

Early Buddhism and Theravāda Buddhism: A Comparative Study By Adesh Barua Introduction In the history of Buddhism, we notice several stages of development. Among these, “Early Buddhism” has been regarded as the most important starting point of Buddhism and also for the later development of Buddhism. It is accepted that Early Buddhism began with the Buddha and gradually developed not only with the community of monks and nuns but also laymen and laywomen. It is also accepted that the original core of early Buddhist teachings are preserved in the Pāli Nikāyas which belongs to the Theravādins. Theravāda Buddhism and its literature are a part of the vast body of doctrines and literary output inspired by the Buddha’s teachings through the centuries. But the controversies as to the origin and meaning of the term Theravāda are not yet over, since Buddhist scholars still debate on the issue. Some have identified Theravāda with Early Buddhism while others are inclined to think that it is one of the Schools that seceded from Early Buddhism. However, in this short paper, I do not wish to reiterate the points that have already been highlighted in researches by different scholars, especially Pāli scholars, and published in their works. I wish here to confine myself only to certain points about the Early Buddhist teachings which are recorded in the Pāli canon and its connection with the language and literature used by Theravādins. And also to highlight the general opinion as to the identification of Theravāda that has come down through generations up to present day in the Theravāda Buddhist countries. -

Metaphor and Literalism in Buddhism

METAPHOR AND LITERALISM IN BUDDHISM The notion of nirvana originally used the image of extinguishing a fire. Although the attainment of nirvana, ultimate liberation, is the focus of the Buddha’s teaching, its interpretation has been a constant problem to Buddhist exegetes, and has changed in different historical and doctrinal contexts. The concept is so central that changes in its understanding have necessarily involved much larger shifts in doctrine. This book studies the doctrinal development of the Pali nirvana and sub- sequent tradition and compares it with the Chinese Agama and its traditional interpretation. It clarifies early doctrinal developments of nirvana and traces the word and related terms back to their original metaphorical contexts. Thereby, it elucidates diverse interpretations and doctrinal and philosophical developments in the abhidharma exegeses and treatises of Southern and Northern Buddhist schools. Finally, the book examines which school, if any, kept the original meaning and reference of nirvana. Soonil Hwang is Assistant Professor in the Department of Indian Philosophy at Dongguk University, Seoul. His research interests are focused upon early Indian Buddhism, Buddhist Philosophy and Sectarian Buddhism. ROUTLEDGE CRITICAL STUDIES IN BUDDHISM General Editors: Charles S. Prebish and Damien Keown Routledge Critical Studies in Buddhism is a comprehensive study of the Buddhist tradition. The series explores this complex and extensive tradition from a variety of perspectives, using a range of different methodologies. The series is diverse in its focus, including historical studies, textual translations and commentaries, sociological investigations, bibliographic studies, and considera- tions of religious practice as an expression of Buddhism’s integral religiosity. It also presents materials on modern intellectual historical studies, including the role of Buddhist thought and scholarship in a contemporary, critical context and in the light of current social issues. -

The Literary Abhidhamma Text: Anuruddha's Manual of Defining Mind and Matter (Namarupapariccheda) and the Production of Pali Commentarial Literature in South India

The Literary Abhidhamma Text: Anuruddha's Manual of Defining Mind and Matter (Namarupapariccheda) and the Production of Pali Commentarial Literature in South India By Sean M. Kerr A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in South and Southeast Asian Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Alexander von Rospatt, Chair Professor Robert P. Goldman Professor Robert H. Sharf Fall 2020 ABSTRACT This dissertation is a study of the ancillary works of the well-known but little understood Pali commentator and Abhidhamma scholar, Anuruddha. Anuruddha's Manual of Defining Mind & Matter (namarupapariccheda) and Decisive Treatment of the Abhidhamma Ultimates (paramatthavinicchaya) are counted among the “sleeping texts” of the Pali commentarial tradition (texts not included in standard curricula, and therefore neglected). Anuruddha's well-studied synopsis of the subject matter of the commentarial-era Abhidhamma tradition, the Compendium of Topics of the Abhidhamma (abhidhammatthasangaha), widely known under its English title, A Comprehensive Manual of Abhidhamma, came to be regarded as the classic handbook of the orthodox Theravadin Abhidhamma system. His lesser-known works, however, curiously fell into obscurity and came to be all but forgotten. In addition to shedding new and interesting light on the Compendium of Topics of the Abhidhamma (abhidhammatthasangaha), these overlooked works reveal another side of the famous author – one as invested in the poetry of his doctrinal expositions as in the terse, unembellished clarity for which he is better remembered. Anuruddha's poetic abhidhamma treatises provide us a glimpse of a little- known early strand of Mahavihara-affiliated commentarial literature infusing the exegetical project with creative and poetic vision. -

The Kathāvatthu Niyāma Debates

THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BUDDHIST STUDIES EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Roger Jackson Depl. of Religion Carleton College Northfield, MN 55057 EDITORS Peter N. Gregory Ernst Steinkellner University of Illinois University of Vienna Vrbana-Champaign, Illinois, USA Wien, Austria Alexander W. Macdonald Jikido Takasaki Universitede Paris X University of Tokyo Nanterre, France Tokyo,Japan Steven Collins Robert Thurman Concordia University Amherst College Montreal, Canada Amherst, Massachusetts, USA Volume 12 1989 Number 1 CONTENTS I. ARTICLES 1. Hodgson's Blind Alley? On the So-called Schools of Nepalese Buddhism by David N. Gellner 7 2. Truth, Contradiction and Harmony in Medieval Japan: Emperor Hanazono (1297-1348) and Buddhism by Andrew Goble 21 3. The Categories of T'i, Hsiang, and Yung: Evidence that Paramartha Composed the Awakening of Faith by William H. Grosnick 65 4. Asariga's Understanding of Madhyamika: Notes on the Shung-chung-lun by John P. Keenan 93 5. Mahayana Vratas in Newar Buddhism by Todd L. Lewis 109 6. The Kathavatthu Niyama Debates by James P McDermott 139 II. SHORT PAPERS 1. A Verse from the Bhadracaripranidhdna in a 10th Century Inscription found at Nalanda by Gregory Schopen 149 2. A Note on the Opening Formula of Buddhist Sutras by Jonathan A. Silk 158 III. BOOK REVIEWS 1. Die Frau imfriihen Buddhismus, by Renata Pitzer-Reyl (Vijitha Rajapakse) 165 Alayavijndna: On the Origin and the Early Development of a Central Concept of Yogacara Philosophy by Iambert Schmithausen (Paul J. Griffiths) 170 LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS 178 The Kathdvatthu Niydma Debates by James P. McDermott A series of debates concerning what has been variously trans lated as "assurance," "fixity," "destiny," and "certitude" (Pali: niydma. -

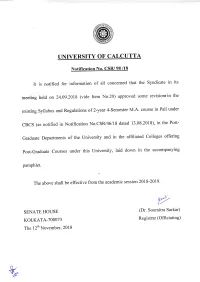

Post-Graduate Syllabus & Regulations --- Department of Pali

UNIVERSITY OF CALCUTTA ADMISSION AND EXAMINATION REGULATIONS FOR SEMESTER-WISE TWO- YEAR MA(FOUR- SEMESTER)IN PALI COURSES OF STUDIES UNDER CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM (CBCS) 2018 1 REGULATION RELATING TO TWO –YEAR (FOUR -SEMESTER) MA DEGREE COURSE OF STUDY IN PALI(CBCS) ATTACHED TO THE POST -GRADUATE FACULTY OF ARTS, UNIVERSITY OF CALCUTTA These Regulations shall come into effect from the academic session 2018-2020. In exercise of the powers conferred by section 54 of the Calcutta University Act, 1979, the Syndicate of the University hereby makes the following Regulations, namely: These Regulations may be called the University of Calcutta (Regulations relating to two year (Four Semesters, CBCS) M.A. Degree Course of Studies in Pali) Regulations, 2018. It shall apply to every candidate prosecuting the above courses in this University. Notwithstanding anything contained in any Regulations or Rules for the time being in force the study of the above course shall be guided by these Regulations. 2 Rules and Regulatons for Two-Year Post Graduate MA Course of study in Pali (CBCS) University of Calcutta 1. To be considered for admission to M.A. in Pali candidate must have obtained B.A. Honours in Pali; BSC,B.COM degree with Honours or equivalent in any Undergraduate subjects like Ancient History & World History, Anthropology, Arabic, Archaeology, Bengali, Buddhist Studies, Comparative Literature, Education, English, French, Hindi, History, Islamic History and Culture, Journalism and Mass Communication, Linguistics, Pali, Persian, Philosophy, Ploitical Science, Sanskrit, Urdu (as Pali is interdisciplinary subject) 2. To be considered for admission to M.A.in Pali candidate may have passed B.A and M.A previous years with any subject (as Pali is mainly traditional and research based subject) .The M.A. -

00-Title JIABU (V.11 No.2).Indd

The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Universities (JIABU) Vol. 11 No.2 (July – December 2018) Aims and Scope The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Universities is an academic journal published twice a year (1st issue January-June, 2nd issue July-December). It aims to promote research and disseminate academic and research articles for researchers, academicians, lecturers and graduate students. The Journal focuses on Buddhism, Sociology, Liberal Arts and Multidisciplinary of Humanities and Social Sciences. All the articles published are peer-reviewed by at least two experts. The articles, submitted for The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Universities, should not be previously published or under consideration of any other journals. The author should carefully follow the submission instructions of The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Universities including the reference style and format. Views and opinions expressed in the articles published by The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Universities, are of responsibility by such authors but not the editors and do not necessarily refl ect those of the editors. Advisors The Most Venerable Prof. Dr. Phra Brahmapundit Rector, Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University, Thailand The Most Venerable Xue Chen Vice President, Buddhist Association of China & Buddhist Academy of China The Most Venerable Dr. Ashin Nyanissara Chancellor, Sitagu International Buddhist Academy, Myanmar Executive Editor Ven. Prof. Dr. Phra Rajapariyatkavi Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University, Thailand ii JIABU | Vol. 11 No.2 (July – December 2018) Chief Editor Ven. Phra Weerasak Jayadhammo (Suwannawong) International Buddhist Studies College (IBSC), Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University, Thailand Editorial Team Ven. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Phramaha Hansa Dhammahaso Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University, Thailand Prof.