Rap and the Construction of Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role Identity Plays in B-Ball Players' and Gangsta Rappers

Vassar College Digital Window @ Vassar Senior Capstone Projects 2016 Playin’ tha game: the role identity plays in b-ball players’ and gangsta rappers’ public stances on black sociopolitical issues Kelsey Cox Vassar College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone Recommended Citation Cox, Kelsey, "Playin’ tha game: the role identity plays in b-ball players’ and gangsta rappers’ public stances on black sociopolitical issues" (2016). Senior Capstone Projects. 527. https://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone/527 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Window @ Vassar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Window @ Vassar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cox playin’ tha Game: The role identity plays in b-ball players’ and gangsta rappers’ public stances on black sociopolitical issues A Senior thesis by kelsey cox Advised by bill hoynes and Justin patch Vassar College Media Studies April 22, 2016 !1 Cox acknowledgments I would first like to thank my family for helping me through this process. I know it wasn’t easy hearing me complain over school breaks about the amount of work I had to do. Mom – thank you for all of the help and guidance you have provided. There aren’t enough words to express how grateful I am to you for helping me navigate this thesis. Dad – thank you for helping me find my love of basketball, without you I would have never found my passion. Jon – although your constant reminders about my thesis over winter break were annoying you really helped me keep on track, so thank you for that. -

G-Eazy & DJ Paul Star in the Movie Tunnel Vision October/November 2017 in the BAY AREA YOUR VIEW IS UNLIMITED

STREET CONSEQUENCES MAGAZINE Exclusive Pull up a seat as Antonio Servidio take us through his life as a Legitimate Hustler & Executive Producer of the movie “Tunnel Vision” Featuring 90’s Bay Area Rappers Street Consequences Presents E-40, Too Short, B-Legit, Spice 1 & The New Talent of Rappers KB, Keak Da Sneak, Rappin 4-Tay Mac Fair & TRAP Q&A with T. A. Corleone Meet the Ladies of Street Consequences G-Eazy & DJ Paul star in the movie Tunnel Vision October/November 2017 IN THE BAY AREA YOUR VIEW IS UNLIMITED October/November 2017 2 October /November 2017 Contents Publisher’s Word Exclusive Interview with Antonio Servidio Featuring the Bay Area Rappers Meet the Ladies of Street Consequences Street Consequences presents new talent of Rappers October/November 2017 3 Publisher’s Words Street Consequences What are the Street Consequences of today’s hustling life- style’s ? Do you know? Do you have any idea? Street Con- sequences Magazine is just what you need. As you read federal inmates whose stories should give you knowledge on just what the street Consequences are. Some of the arti- cles in this magazine are from real people who are in jail because of these Street Consequences. You will also read their opinion on politics and their beliefs on what we, as people, need to do to chance and make a better future for the up-coming youth of today. Stories in this magazine are from big timer in the games to small street level drug dealers and regular people too, Hopefully this magazine will open up your eyes and ears to the things that are going on around you, and have to make a decision that will make you not enter into the game that will leave you dead or in jail. -

Respiratory Support

Intensive Care Nursery House Staff Manual Respiratory Support ABBREVIATIONS FIO2 Fractional concentration of O2 in inspired gas PaO2 Partial pressure of arterial oxygen PAO2 Partial pressure of alveolar oxygen PaCO2 Partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide PACO2 Partial pressure of alveolar carbon dioxide tcPCO2 Transcutaneous PCO2 PBAR Barometric pressure PH2O Partial pressure of water RQ Respiratory quotient (CO2 production/oxygen consumption) SaO2 Arterial blood hemoglobin oxygen saturation SpO2 Arterial oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry PIP Peak inspiratory pressure PEEP Positive end-expiratory pressure CPAP Continuous positive airway pressure PAW Mean airway pressure FRC Functional residual capacity Ti Inspiratory time Te Expiratory time IMV Intermittent mandatory ventilation SIMV Synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation HFV High frequency ventilation OXYGEN (Oxygen is a drug!): A. Most infants require only enough O2 to maintain SpO2 between 87% to 92%, usually achieved with PaO2 of 40 to 60 mmHg, if pH is normal. Patients with pulmonary hypertension may require a much higher PaO2. B. With tracheal suctioning, it may be necessary to raise the inspired O2 temporarily. This should not be ordered routinely but only when the infant needs it. These orders are good for only 24h. OXYGEN DELIVERY and MEASUREMENT: A. Oxygen blenders allow O2 concentration to be adjusted between 21% and 100%. B. Head Hoods permit non-intubated infants to breathe high concentrations of humidified oxygen. Without a silencer they can be very noisy. C. Nasal Cannulae allow non-intubated infants to breathe high O2 concentrations and to be less encumbered than with a head hood. O2 flows of 0.25-0.5 L/min are usually sufficient to meet oxygen needs. -

E-40 Album Download DOWNLOAD ALBUM: Too Short & E-40 -Ain’T Gone Do It Terms and Conditions ZIP

e-40 album download DOWNLOAD ALBUM: Too Short & E-40 -Ain’t Gone Do It Terms and Conditions ZIP. DOWNLOAD Too Short & E-40 Ain’t Gone Do It Terms and Conditions ZIP & MP3 File. Ever Trending Star drops this amazing song titled “Too Short & E-40 – Ain’t Gone Do It Terms and Conditions Album“, its available for your listening pleasure and free download to your mobile devices or computer. You can Easily Stream & listen to this new “ FULL ALBUM: Too Short & E-40 – Ain’t Gone Do It Terms and Conditions Zip File” free mp3 download” 320kbps, cdq, itunes, datafilehost, zip, torrent, flac, rar zippyshare fakaza Song below. E-40 album download. Artist: E-40 And B-Legit Album: Connected And Respected Released: 2018 Style: Hip Hop. Format: MP3 320Kbps. Tracklist: 01 – Life Lessons 02 – Straight Like That 03 – Boy 04 – Guilty By Association 05 – Carpal Tunnel 06 – Stompdown (Skit 1) 07 – Meet The Dealers 08 – Get It On My Own 09 – Up Against It 10 – Fsho 11 – Whooped 12 – Tap In 13 – You Ah Lie 14 – Need To Know 15 – Stompdown (Skit 2) 16 – Bare 17 – Barbershop 18 – Blame It 19 – So High. DOWNLOAD LINKS: RAPIDGATOR: DOWNLOAD TURBOBIT: DOWNLOAD. E-40 Discography @ 320 (21 Albums+1)(RAP)(by dragan09) 1990 - E-40 - Mr. Flamboyant @192 1994 - E-40 - Federal 1994 - E-40 - The Mail Man (EP) 1995 - E-40 - In a Major Way 1996 - E-40 - Tha Hall of Game 1997 - E-40 & B-Legit - Southwest Riders (2 CD`s) 1998 - E-40 - The Element Of Surprise (2 CD`s) 1999 - E-40 - Charlie Hustle - The Blueprint of a Self-Made Millionaire 2000 - E-40 - Loyalty and Betrayal 2002 - E-40 - Grit & Grind 2003 - E-40 - Breakin' News 2004 - E-40 - My Ghetto Report Card 2008 - E-40 - The Ball Street Journal 2010 - E-40 - Revenue Retrievin' Day Shift 2010 - E-40 - Revenue Retrievin' Night Shift 2011 - E-40 - Revenue Retrievin'. -

Small Door Veterinary

CAT PARENTING 101 Everything you need to know about caring for your new cat. Cat Parenting 101 | Page 2 CONGRATULATIONS! Welcoming a new cat into your family is one of the most rewarding experiences in life, and we’re so excited for you to get to know your new furry family member over the coming days and weeks. As a new cat owner, there’s a lot to learn, so we’ve put together this comprehensive guide to help you navigate cat parenthood. Remember – as a Small Door member, you can contact us 24/7 via the app for advice or if you ever have any concerns about your new kitty. Best of luck, and we can’t wait to meet you both at the practice soon! CONTENTS Page 3 The essentials, on one page Page 22 Grooming Page 22 Nail trimming Page 4 Bringing your new cat home Page 23 Ear cleaning Page 4 Preparing your home Page 5 The first day with your new cat Page 24 Medical care Page 5 Introducing your cat to other pets Page 24 Vaccinations Page 25 Vaccine reactions Page 7 Socialization Page 25 Preventatives Page 26 Wellness care schedules Page 8 Stimulation, exercise & play Page 27 Indoor cats Page 8 Toys Page 28 Spaying and neutering Page 10 How to play with your cat Page 29 Dental health Page 11 How much playtime do cats need? Page 30 How to brush your cat’s teeth Page 11 Catios for indoor cats Page 31 Microchipping Page 12 Behavior & training Page 31 Pet insurance Page 12 Positive reinforcement Page 32 Developing a positive vet experience Page 12 Discouraging unwanted behaviors Page 33 Common problems & when to seek help Page 14 Litter box training Page -

Basquiat and the Bayou,’ the No

The Times-Picayune October 20, 2014 GAGOSIAN GALLERY ‘Basquiat and the Bayou,’ the No. 1 Prospect.3 art festival stop in New Orleans Doug MacCash Franklin Sirmans, artistic director, Prospect.3 international art festival in New Orleans (Photo by Doug MacCash / NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune) Though he died at age 27 in 1988, artist Jean-Michel Basquiat remains among the brightest of American art stars. For a short time, he was a street artist in New York’s burgeoning 1970s graffiti scene. His tag, SAMO, became a graffiti icon. Not long after, Basquiat climbed to the highest rungs of the rarified Manhattan art world, eventually even collaborating on paintings with pop legend Andy Warhol. His celebrity was almost unparalleled among visual artists. His expressionist paintings now hang in museums across the globe and sell for tens of millions. Reebok recently released a line of athletic shoes decorated with Basquiat images. A suite of nine of Basquiat’s artworks based on Southern themes has been assembled for the first time ever on the Ogden Museum of Southern Art’s fifth floor. The exhibit, “Basquiat and the Bayou,” is certain to be the most popular stop during the Prospect.3 art festival that opens Oct. 25 and continues through Jan. 25, 2015. Franklin Sirmans, the artistic director of Prospect.3, has studied Basquiat for years. During a visit to the Ogden on Saturday (Oct. 18), Sirmans explained the amazing persistence of the artist’s popularity. Basquiat, as part of the New York graffiti and club scene in the 1970s and ‘80s, became a link to the beginnings of hip-hop culture, Sirmans said. -

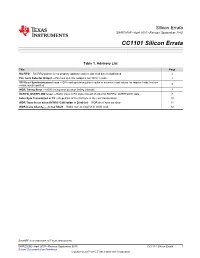

CC1101 Silicon Errata (Rev. E)

Silicon Errata SWRZ020E–April 2007–Revised September 2015 CC1101 Silicon Errata Table 1. Advisory List Title Page RX FIFO —RX FIFO pointer is not properly updated and the last read byte is duplicated 2 PLL Lock Detector Output —PLL lock detector output is not 100% reliable 3 SPI Read Synchronization Issue —SPI read synchronization results in incorrect read values for register fields that are 4 continuously updated WOR Timing Error —WOR timing error on short timing intervals 7 RXFIFO_OVERFLOW Issue —Radio stays in RX state instead of entering RXFIFO_OVERFLOW state 8 Extra Byte Transmitted in TX —Repetition of the first byte in the next transmission 10 WOR Timer Issue when RCOSC Calibration is Disabled —WOR timer runs too slow 11 WOR Issue when tEvent1 is too Short —Radio not entering RX in WOR mode 12 SmartRF is a trademark of Texas Instruments. SWRZ020E–April 2007–Revised September 2015 CC1101 Silicon Errata 1 Submit Documentation Feedback Copyright © 2007–2015, Texas Instruments Incorporated RX FIFO — RX FIFO pointer is not properly updated and the last read byte is duplicated www.ti.com RX FIFO RX FIFO pointer is not properly updated and the last read byte is duplicated Revision(s) Affected This errata note applies to all batches and revisions of the chip. Details If a received data byte is written to the RX FIFO at the exact same time as the last byte in the RX FIFO is read over the SPI interface, the RX FIFO pointer is not properly updated and the last read byte is duplicated. Workaround(s) For packets below 64 bytes, it is recommended to wait until the complete packet has been received before reading it out. -

The Effects of Hip-Hop and Rap on Young Women in Academia

The Effects of Hip-Hop and Rap on Young Women in Academia by Sandra C Zichermann A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education Sociology in Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Sandra C Zichermann 2013 The Effects of Hip-Hop and Rap on Young Women in Academia Sandra C Zichermann Doctor of Education Sociology in Education University of Toronto 2013 Abstract This thesis investigates the rise of the cultures and music of hip-hop and rap in the West and its effects on its female listeners and fans, especially those in academia. The thesis consists of two parts. First I conducted a content analysis of 95 lyrics from the book, Hip-Hop & Rap: Complete Lyrics for 175 Songs (Spence, 2003). The songs I analyzed were performed by male artists whose lyrics repeated misogynist and sexist messages. Second, I conducted a focus group with young female university students who self-identify as fans of hip-hop and/or rap music. In consultation with my former thesis supervisor, I selected women enrolled in interdisciplinary programmes focused on gender and race because they are equipped with an academic understanding of the potential damage or negative effects of anti-female or negative political messaging in popular music. My study suggests that the impact of hip-hop and rap music on young women is both positive and negative, creating an overarching feeling of complexity for some young female listeners who enjoy music that is infused with some lyrical messages they revile. -

Journal of Hip Hop Studies

et al.: Journal of Hip Hop Studies June 2016 Published by VCU Scholars Compass, 2016 1 Journal of Hip Hop Studies, Vol. 3 [2016], Iss. 1, Art. 1 Editor in Chief: Daniel White Hodge, North Park University Senior Editorial Advisory Board: Anthony Pinn, Rice University James Paterson, Lehigh University Book Review Editor: Gabriel B. Tait, Arkansas State University Associate Editors: Cassandra Chaney, Louisiana State University Jeffrey L. Coleman, St. Mary’s College of Maryland Monica Miller, Lehigh University Associate & Copy Editor: Travis Harris, PhD Student, College of William and Mary Editorial Board: Dr. Rachelle Ankney, North Park University Dr. Jason J. Campbell, Nova Southeastern University Dr. Jim Dekker, Cornerstone University Ms. Martha Diaz, New York University Mr. Earle Fisher, Rhodes College/Abyssinian Baptist Church, United States Dr. Daymond Glenn, Warner Pacific College Dr. Deshonna Collier-Goubil, Biola University Dr. Kamasi Hill, Interdenominational Theological Center Dr. Andre E. Johnson, University of Memphis Dr. David Leonard, Washington State University Dr. Terry Lindsay, North Park University Ms. Velda Love, North Park University Dr. Anthony J. Nocella II, Hamline University Dr. Priya Parmar, SUNY Brooklyn, New York Dr. Soong-Chan Rah, North Park University Dr. Rupert Simms, North Park University Dr. Darron Smith, University of Tennessee Health Science Center Dr. Jules Thompson, University Minnesota, Twin Cities Dr. Mary Trujillo, North Park University Dr. Edgar Tyson, Fordham University Dr. Ebony A. Utley, California State University Long Beach, United States Dr. Don C. Sawyer III, Quinnipiac University https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/jhhs/vol3/iss1/1 2 et al.: Journal of Hip Hop Studies . Sponsored By: North Park Universities Center for Youth Ministry Studies (http://www.northpark.edu/Centers/Center-for-Youth-Ministry-Studies) Save The Kids Foundation (http://savethekidsgroup.org/) Published by VCU Scholars Compass, 2016 3 Journal of Hip Hop Studies, Vol. -

The Not So Short Introduction to L Atex2ε

The Not So Short Introduction to LATEX 2" Or LATEX 2" in 139 minutes by Tobias Oetiker Hubert Partl, Irene Hyna and Elisabeth Schlegl Version 6.4, March 09, 2021 ii Copyright ©1995-2021 Tobias Oetiker and Contributors. All rights reserved. This document is free; you can redistribute it and/or modify it under the terms of the GNU General Public License as published by the Free Software Foundation; either version 2 of the License, or (at your option) any later version. This document is distributed in the hope that it will be useful, but without any warranty; without even the implied warranty of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. See the GNU General Public License for more details. You should have received a copy of the GNU General Public License along with this document; if not, write to the Free Software Foundation, Inc., 51 Franklin Street, Fifth Floor, Boston, MA 02110-1301, USA. Thank you! Much of the material used in this introduction comes from an Austrian introduction to LATEX 2.09 written in German by: Hubert Partl <[email protected]> Zentraler Informatikdienst der Universität für Bodenkultur Wien Irene Hyna <[email protected]> Bundesministerium für Wissenschaft und Forschung Wien Elisabeth Schlegl <noemail> in Graz If you are interested in the German document, you can find a version updated for LATEX 2" by Jörg Knappen at CTAN://info/lshort/german iv Thank you! The following individuals helped with corrections, suggestions and material to improve this paper. They put in a big effort to help me get this document into its present shape. -

13-983 Brief for the Marion B. Brechner First

NO. 13-983 In the Supreme Court of the United States ANTHONY DOUGLAS ELONIS, Petitioner, v. UNITED STATES, Respondent. On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit AMICI CURIAE BRIEF OF THE MARION B. BRECHNER FIRST AMENDMENT PROJECT AND RAP MUSIC SCHOLARS (PROFESSORS ERIK NIELSON AND CHARIS E. KUBRIN) IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER CLAY CALVERT Counsel of Record MARION B. BRECHNER FIRST A MENDMENT P ROJECT 2060 Weimer Hall Gainesville, FL 32611 (352) 273-1096 [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae August 18, 2014 Becker Gallagher · Cincinnati, OH · Washington, D.C. · 800.890.5001 i TABLE OF CONTENTS INTERESTS OF AMICI CURIAE .............. 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.................. 2 ARGUMENT............................... 6 I. Origins of Hip Hop and Rap.............. 6 II. The Complexity, Hyperbole, and Rhetoric of Rap: Meanings Lost in Translation........ 8 III. Fear of Rap: Another Moral Panic ........ 17 IV. Rap is Art, Even If It Often is Misinterpreted and Misunderstood.................... 21 CONCLUSION ............................ 24 ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CASES: Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association, 131 S. Ct. 2729 (2011) .................... 17 Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, 558 U.S. 310 (2010) ...................... 11 Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15 (1971) .................... 18, 24 Illinois v. Oduwole, 985 N.E.2d 316 (Ill. App. Ct. 2013), appeal denied, 2013 Ill. LEXIS 796 (Ill. May 29, 2013) ........................ 4 In re S.W., 45 A.3d 151 (D.C. Cir. 2012) ................ 4 New Jersey v. Skinner, 2014 N.J. LEXIS 803 (N.J. Aug. 4, 2014) ..... 17 United States v. Elonis, 730 F.3d 321 (3d Cir. -

Poem #1 It Was After Dinner in the Suburbs the Lovely Time Where

Poem #1 It was after dinner in the suburbs just this, I said, the lovely time where everybody looks trying to convince her into the dusk, the sunset that with the chirp in my voice they would promise to watch that it could’ve been an some other time onslaught of rotting apple they pretend to be thinking stuffed in a ramekin about tomorrow’s tasks but look, it was only an extra thing for her to wash and my mother, who was maybe thinking something and as she reached for the cup sweeter, with fingers wrinkled from was standing at the sink, the scalding water the crickets and trees just above her that got everything pure, downcast angle of vision, I took the teabag out and and she was washing the dishes threw it away anything else, she would ask I felt happy then, anything left upstairs, an too short to look out the window unfinished cup of water at the sunset I thought was still there, that I can wash, make new again? I was happy because I thought the teabag would and I raced upstairs show how kind I was, making up back down again for her doing the dishes two at a time by this time but now I’m tall enough it was dark to see the dark, the crickets everybody, like always, have gone under the snow had missed the sunset, and I think how my mother and I handed her a teacup used to wash the dishes to make up for all the bad things she thought she had ever done to me.