Basquiat and the Bayou,’ the No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daft Punk Collectible Sales Skyrocket After Breakup: 'I Could've Made

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE APRIL 13, 2020 | PAGE 4 OF 19 ON THE CHARTS JIM ASKER [email protected] Bulletin SamHunt’s Southside Rules Top Country YOURAlbu DAILYms; BrettENTERTAINMENT Young ‘Catc NEWSh UPDATE’-es Fifth AirplayFEBRUARY 25, 2021 Page 1 of 37 Leader; Travis Denning Makes History INSIDE Daft Punk Collectible Sales Sam Hunt’s second studio full-length, and first in over five years, Southside sales (up 21%) in the tracking week. On Country Airplay, it hops 18-15 (11.9 mil- (MCA Nashville/Universal Music Group Nashville), debutsSkyrocket at No. 1 on Billboard’s lion audience After impressions, Breakup: up 16%). Top Country• Spotify Albums Takes onchart dated April 18. In its first week (ending April 9), it earned$1.3B 46,000 in equivalentDebt album units, including 16,000 in album sales, ac- TRY TO ‘CATCH’ UP WITH YOUNG Brett Youngachieves his fifth consecutive cording• Taylor to Nielsen Swift Music/MRCFiles Data. ‘I Could’veand total Made Country Airplay No.$100,000’ 1 as “Catch” (Big Machine Label Group) ascends SouthsideHer Own marks Lawsuit Hunt’s in second No. 1 on the 2-1, increasing 13% to 36.6 million impressions. chartEscalating and fourth Theme top 10. It follows freshman LP BY STEVE KNOPPER Young’s first of six chart entries, “Sleep With- MontevalloPark, which Battle arrived at the summit in No - out You,” reached No. 2 in December 2016. He vember 2014 and reigned for nine weeks. To date, followed with the multiweek No. 1s “In Case You In the 24 hours following Daft Punk’s breakup Thomas, who figured out how to build the helmets Montevallo• Mumford has andearned Sons’ 3.9 million units, with 1.4 Didn’t Know” (two weeks, June 2017), “Like I Loved millionBen in Lovettalbum sales. -

Alicia Keys Releases Emotional New Song “Perfect Way to Die”

ALICIA KEYS RELEASES EMOTIONAL NEW SONG “PERFECT WAY TO DIE” “Of course there is no perfect way to die. This phrase doesn’t even make sense but that’s what makes the title so powerful and heartbreaking because so many have died unjustly. It’s written from the point of view of the mother whose child has been murdered because of the system of racism that looks at Black life as unworthy. We all know none of these innocent lives should have been taken due to the culture of police violence.” – Alicia Keys The Grammy Winner Set to Give a Special Performance of the Song during the BET Awards Broadcast on June 28 STREAM “PERFECT WAY TO DIE” DOWNLOAD ARTWORK AND LYRICS NEW YORK, NY (June 19, 2020) -- According to Alicia, “Of course there is no perfect way to die. This phrase doesn’t even make sense but that’s what makes the title so powerful and heartbreaking because so many have died unjustly. It’s written from the point of view of the mother whose child has been murdered because of the system of racism that looks at Black life as unworthy. We all know none of these innocent lives should have been taken due to the culture of police violence.” Listen to “Perfect Way To Die” across digital platforms HERE. As the outrage and protests over the repeated killings of unarmed black men and women by police and systemic racism continues, 15-time GRAMMY Award-winning singer/songwriter/producer Keys has not only joined the chorus of those who are demanding justice, but has also channeled those feelings into a haunting new ballad, “Perfect Way to Die,” out today. -

Cassidy BARS Full Album Zip

Cassidy BARS Full Album Zip 1 / 5 Cassidy BARS Full Album Zip 2 / 5 3 / 5 Get down after dark with more bars than any ship out there and savor a world of ... cruise ships are full of adventures guaranteed to wow every kind of explorer. ... If you're chasing thrills, try a white-knuckle zip line ride nine stories above the .... Jun 12, 2020 — Tags: Cassidy - Bars Is Back mp3, stream & download Cassidy - Bars Is Back mp3 zip, download Cassidy - Bars Is Back mp3 song, Cassidy .... Dec 20, 2017 — There is a new release by Eva Cassidy called "Acoustic", which appears to ... But even if it is a compilation of takes of songs from exiting albums and there is ... So, the plan quickly emerged that I would restore it and create a full ... last 8 bars of the first chorus (“Somewhere over the rainbow, bluebirds fly…”).. ... Votes @ Eva's Sports Bar (Outside) 736 A Philip Randolph Blvd, Jacksonville, ... VIPSquadNation.com to download in FULL for FREE] -- Florida's Finest 7 ... Bangem Banzz | Cassidy| Chris Rivers | Cardi B | Wiz Khalifa | Nipsey Hussle | Lil ... ://www.mediafire.com/file/iqcjhytk71d394t/Freestyile_Filez_6_FULL_Final.zip/file.. Download/Stream Cassidy's mixtape, Da BARbarian, for Free at MixtapeMonkey.com - Download/Stream Free Mixtapes and Music Videos from your favorite ... Mar 16, 2021 — singham returns 320 kbps mp3 download Singham Returns [2014-MP3-VBR-320Kbps] MN Singham ... Cassidy, B.A.R.S. Full Album Zip. cassidy bars cassidy bars, cassidy barsdorf, cassidy bars is back lyrics, pat cassidy barstool, best cassidy bars, delta cassidy towel bars, cassidy who got bars, cassidy 100 bars lyrics, cassidy towel bars, zoe barsanti cassidy, cassidy best bars Jun 11, 2021 — The fifth installment of the rapper-producer's long-running series lands closer to the sweet spot between beats and bars glimpsed on his ... -

Reflections from Djs Rearranging Relations and Improvising Continuity

Critical Studies in Improvisation / Études critiques en improvisation, Vol. 14, No. 2–3 #djlife During the Pandemic: Reflections from DJs Rearranging Relations and Improvising Continuity Mark V. Campbell and Ayşe Barut Across multiple social media platforms, the hashtag #djlife has offered a glimpse into what DJs do in both their online and offline lives. Some DJs post their remixes, others post their practice sessions or their latest booking. Globally, as nightclubs closed their doors and festivals cancelled their 2020 editions in response to COVID-19, DJs were forced to reconsider how to maintain their livelihoods. Like most performers in popular culture, the DJ’s public visibility is tied to their continued relevance, so with two major arenas—festivals and nightclubs—closed, DJs had to quickly find a way to engage their fans. For many DJs, livestreaming themselves mixing records became a way to continue connecting with their fans. While several DJs were already livestreaming, such as DJ Mel Boogie on her Toronto-based radio show Studio B on Vibe 105 FM, many more delved into streaming for the first time during the pandemic. Platforms such as Facebook and Instagram became the go-to sites for various kinds of livestream events during the pandemic. Verzuz, a visual webcast series presented, created, and launched by multi-platinum producers Timbaland and Swizz Beatz at the end of March 2020, quickly established viewership records as it went viral. Each Verzuz online event features two prominent recording artists squaring off “against” each other in a friendly competition, each sharing their esteemed catalogues. With high profile artists in events such as Jill Scott vs. -

The Role Identity Plays in B-Ball Players' and Gangsta Rappers

Vassar College Digital Window @ Vassar Senior Capstone Projects 2016 Playin’ tha game: the role identity plays in b-ball players’ and gangsta rappers’ public stances on black sociopolitical issues Kelsey Cox Vassar College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone Recommended Citation Cox, Kelsey, "Playin’ tha game: the role identity plays in b-ball players’ and gangsta rappers’ public stances on black sociopolitical issues" (2016). Senior Capstone Projects. 527. https://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone/527 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Window @ Vassar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Window @ Vassar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cox playin’ tha Game: The role identity plays in b-ball players’ and gangsta rappers’ public stances on black sociopolitical issues A Senior thesis by kelsey cox Advised by bill hoynes and Justin patch Vassar College Media Studies April 22, 2016 !1 Cox acknowledgments I would first like to thank my family for helping me through this process. I know it wasn’t easy hearing me complain over school breaks about the amount of work I had to do. Mom – thank you for all of the help and guidance you have provided. There aren’t enough words to express how grateful I am to you for helping me navigate this thesis. Dad – thank you for helping me find my love of basketball, without you I would have never found my passion. Jon – although your constant reminders about my thesis over winter break were annoying you really helped me keep on track, so thank you for that. -

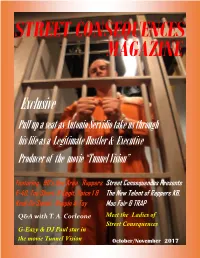

G-Eazy & DJ Paul Star in the Movie Tunnel Vision October/November 2017 in the BAY AREA YOUR VIEW IS UNLIMITED

STREET CONSEQUENCES MAGAZINE Exclusive Pull up a seat as Antonio Servidio take us through his life as a Legitimate Hustler & Executive Producer of the movie “Tunnel Vision” Featuring 90’s Bay Area Rappers Street Consequences Presents E-40, Too Short, B-Legit, Spice 1 & The New Talent of Rappers KB, Keak Da Sneak, Rappin 4-Tay Mac Fair & TRAP Q&A with T. A. Corleone Meet the Ladies of Street Consequences G-Eazy & DJ Paul star in the movie Tunnel Vision October/November 2017 IN THE BAY AREA YOUR VIEW IS UNLIMITED October/November 2017 2 October /November 2017 Contents Publisher’s Word Exclusive Interview with Antonio Servidio Featuring the Bay Area Rappers Meet the Ladies of Street Consequences Street Consequences presents new talent of Rappers October/November 2017 3 Publisher’s Words Street Consequences What are the Street Consequences of today’s hustling life- style’s ? Do you know? Do you have any idea? Street Con- sequences Magazine is just what you need. As you read federal inmates whose stories should give you knowledge on just what the street Consequences are. Some of the arti- cles in this magazine are from real people who are in jail because of these Street Consequences. You will also read their opinion on politics and their beliefs on what we, as people, need to do to chance and make a better future for the up-coming youth of today. Stories in this magazine are from big timer in the games to small street level drug dealers and regular people too, Hopefully this magazine will open up your eyes and ears to the things that are going on around you, and have to make a decision that will make you not enter into the game that will leave you dead or in jail. -

UNDERSTANDING PORTRAYALS of LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS in HIP-HOP LYRICS SINCE 2009 By

ON THE BEAT: UNDERSTANDING PORTRAYALS OF LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS IN HIP-HOP LYRICS SINCE 2009 by Francesca A. Keesee A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degrees of Master of Science Conflict Analysis and Resolution Master of Arts Conflict Resolution and Mediterranean Security Committee: ___________________________________________ Chair of Committee ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Graduate Program Director ___________________________________________ Dean, School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution Date: _____________________________________ Fall Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, VA University of Malta Valletta, Malta On the Beat: Understanding Portrayals of Law Enforcement Officers in Hip-hop Lyrics Since 2009 A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees of Master of Science at George Mason University and Master of Arts at the University of Malta by Francesca A. Keesee Bachelor of Arts University of Virginia, 2015 Director: Juliette Shedd, Professor School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution Fall Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, Virginia University of Malta Valletta, Malta Copyright 2016 Francesca A. Keesee All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to all victims of police brutality. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am forever grateful to my best friend, partner in crime, and husband, Patrick. -

Respiratory Support

Intensive Care Nursery House Staff Manual Respiratory Support ABBREVIATIONS FIO2 Fractional concentration of O2 in inspired gas PaO2 Partial pressure of arterial oxygen PAO2 Partial pressure of alveolar oxygen PaCO2 Partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide PACO2 Partial pressure of alveolar carbon dioxide tcPCO2 Transcutaneous PCO2 PBAR Barometric pressure PH2O Partial pressure of water RQ Respiratory quotient (CO2 production/oxygen consumption) SaO2 Arterial blood hemoglobin oxygen saturation SpO2 Arterial oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry PIP Peak inspiratory pressure PEEP Positive end-expiratory pressure CPAP Continuous positive airway pressure PAW Mean airway pressure FRC Functional residual capacity Ti Inspiratory time Te Expiratory time IMV Intermittent mandatory ventilation SIMV Synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation HFV High frequency ventilation OXYGEN (Oxygen is a drug!): A. Most infants require only enough O2 to maintain SpO2 between 87% to 92%, usually achieved with PaO2 of 40 to 60 mmHg, if pH is normal. Patients with pulmonary hypertension may require a much higher PaO2. B. With tracheal suctioning, it may be necessary to raise the inspired O2 temporarily. This should not be ordered routinely but only when the infant needs it. These orders are good for only 24h. OXYGEN DELIVERY and MEASUREMENT: A. Oxygen blenders allow O2 concentration to be adjusted between 21% and 100%. B. Head Hoods permit non-intubated infants to breathe high concentrations of humidified oxygen. Without a silencer they can be very noisy. C. Nasal Cannulae allow non-intubated infants to breathe high O2 concentrations and to be less encumbered than with a head hood. O2 flows of 0.25-0.5 L/min are usually sufficient to meet oxygen needs. -

E-40 Album Download DOWNLOAD ALBUM: Too Short & E-40 -Ain’T Gone Do It Terms and Conditions ZIP

e-40 album download DOWNLOAD ALBUM: Too Short & E-40 -Ain’t Gone Do It Terms and Conditions ZIP. DOWNLOAD Too Short & E-40 Ain’t Gone Do It Terms and Conditions ZIP & MP3 File. Ever Trending Star drops this amazing song titled “Too Short & E-40 – Ain’t Gone Do It Terms and Conditions Album“, its available for your listening pleasure and free download to your mobile devices or computer. You can Easily Stream & listen to this new “ FULL ALBUM: Too Short & E-40 – Ain’t Gone Do It Terms and Conditions Zip File” free mp3 download” 320kbps, cdq, itunes, datafilehost, zip, torrent, flac, rar zippyshare fakaza Song below. E-40 album download. Artist: E-40 And B-Legit Album: Connected And Respected Released: 2018 Style: Hip Hop. Format: MP3 320Kbps. Tracklist: 01 – Life Lessons 02 – Straight Like That 03 – Boy 04 – Guilty By Association 05 – Carpal Tunnel 06 – Stompdown (Skit 1) 07 – Meet The Dealers 08 – Get It On My Own 09 – Up Against It 10 – Fsho 11 – Whooped 12 – Tap In 13 – You Ah Lie 14 – Need To Know 15 – Stompdown (Skit 2) 16 – Bare 17 – Barbershop 18 – Blame It 19 – So High. DOWNLOAD LINKS: RAPIDGATOR: DOWNLOAD TURBOBIT: DOWNLOAD. E-40 Discography @ 320 (21 Albums+1)(RAP)(by dragan09) 1990 - E-40 - Mr. Flamboyant @192 1994 - E-40 - Federal 1994 - E-40 - The Mail Man (EP) 1995 - E-40 - In a Major Way 1996 - E-40 - Tha Hall of Game 1997 - E-40 & B-Legit - Southwest Riders (2 CD`s) 1998 - E-40 - The Element Of Surprise (2 CD`s) 1999 - E-40 - Charlie Hustle - The Blueprint of a Self-Made Millionaire 2000 - E-40 - Loyalty and Betrayal 2002 - E-40 - Grit & Grind 2003 - E-40 - Breakin' News 2004 - E-40 - My Ghetto Report Card 2008 - E-40 - The Ball Street Journal 2010 - E-40 - Revenue Retrievin' Day Shift 2010 - E-40 - Revenue Retrievin' Night Shift 2011 - E-40 - Revenue Retrievin'. -

Open Steinle Cory Kanyecriticism.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION ARTS & SCIENCES “I THOUGHT ABOUT KILLING YOU”: CONSIDERING THE UTILITY OF RHETORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL CRITICAL APPROACHES TO KANYE WEST’S YE CORY N. STEINLE SPRING 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Communication Arts and Sciences and Labor and Employment Relations with honors in Communication Arts and Sciences Reviewed and approved* by the following: Bradford Vivian Professor of Communication Arts & Sciences Thesis Supervisor Lori Bedell Associate Teaching Professor in Communication Arts & Sciences Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT This paper examines the merits of intrinsic and extrinsic critical approaches to hip-hop artifacts. To do so, I provide both a neo-Aristotelian and biographical criticism of three songs from ye (2018) by Kanye West. Chapters 1 & 2 consider Roland Barthes’ The Death of the Author and other landmark papers in rhetorical and literary theory to develop an intrinsic and extrinsic approach to criticizing ye (2018), evident in Tables 1 & 2. Chapter 3 provides the biographical antecedents of West’s life prior to the release of ye (2018). Chapters 4, 5, & 6 supply intrinsic (neo-Aristotelian) and extrinsic (biographical) critiques of the selected artifacts. Each of these chapters aims to address the concerns of one of three guiding questions: which critical approaches prove most useful to the hip-hop consumer listening to this song? How can and should the listener construct meaning? Are there any improper ways to critique and interpret this song? Chapter 7 discusses the variance in each mode of critical analysis from Chapters 4, 5, & 6. -

Small Door Veterinary

CAT PARENTING 101 Everything you need to know about caring for your new cat. Cat Parenting 101 | Page 2 CONGRATULATIONS! Welcoming a new cat into your family is one of the most rewarding experiences in life, and we’re so excited for you to get to know your new furry family member over the coming days and weeks. As a new cat owner, there’s a lot to learn, so we’ve put together this comprehensive guide to help you navigate cat parenthood. Remember – as a Small Door member, you can contact us 24/7 via the app for advice or if you ever have any concerns about your new kitty. Best of luck, and we can’t wait to meet you both at the practice soon! CONTENTS Page 3 The essentials, on one page Page 22 Grooming Page 22 Nail trimming Page 4 Bringing your new cat home Page 23 Ear cleaning Page 4 Preparing your home Page 5 The first day with your new cat Page 24 Medical care Page 5 Introducing your cat to other pets Page 24 Vaccinations Page 25 Vaccine reactions Page 7 Socialization Page 25 Preventatives Page 26 Wellness care schedules Page 8 Stimulation, exercise & play Page 27 Indoor cats Page 8 Toys Page 28 Spaying and neutering Page 10 How to play with your cat Page 29 Dental health Page 11 How much playtime do cats need? Page 30 How to brush your cat’s teeth Page 11 Catios for indoor cats Page 31 Microchipping Page 12 Behavior & training Page 31 Pet insurance Page 12 Positive reinforcement Page 32 Developing a positive vet experience Page 12 Discouraging unwanted behaviors Page 33 Common problems & when to seek help Page 14 Litter box training Page -

Triller Network Acquires Verzuz: Exclusive

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE APRIL 13, 2020 | PAGE 4 OF 19 ON THE CHARTS JIM ASKER [email protected] Bulletin SamHunt’s Southside Rules Top Country YOURAlbu DAILYms; BrettENTERTAINMENT Young ‘Catc NEWSh UPDATE’-es Fifth AirplayMARCH 9, 2021 Page 1 of 25 Leader; Travis Denning Makes History INSIDE Triller Network Acquires Sam Hunt’s second studio full-length, and first in over five years, Southside sales (up 21%) in the tracking week. On Country Airplay, it hops 18-15 (11.9 mil- (MCA Nashville/Universal Music Group Nashville), debuts at No. 1 on Billboard’s lion audience impressions, up 16%). Top Country• Verzuz Albums Founders chart dated April 18. In its first week (endingVerzuz: April 9), it Exclusive earnedSwizz 46,000 Beatz equivalent & album units, including 16,000 in album sales, ac- TRY TO ‘CATCH’ UP WITH YOUNG Brett Youngachieves his fifth consecutive cordingTimbaland to Nielsen Talk Music/MRC Data. andBY total GAIL Country MITCHELL Airplay No. 1 as “Catch” (Big Machine Label Group) ascends SouthsideTriller Partnership: marks Hunt’s second No. 1 on the 2-1, increasing 13% to 36.6 million impressions. chart‘This and fourthPuts a top Light 10. It followsVerzuz, freshman the LPpopular livestream music platform creat- in music todayYoung’s than Verzuz,” first of six said chart Bobby entries, Sarnevesht “Sleep With,- MontevalloBack on, which Creatives’ arrived at theed summit by Swizz in No Beatz- and Timbaland, has been acquired executive chairmanout You,” andreached co-owner No. 2 in of December Triller, in 2016. an- He vember 2014 and reigned for nineby weeks. Triller To Network, date, parent company of the Triller app.