UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stage Violence, Power and the Director an Examination

STAGE VIOLENCE, POWER AND THE DIRECTOR AN EXAMINATION OF THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF CRUELTY FROM ANTONIN ARTAUD TO SARAH KANE by Jordan Matthew Walsh Bachelor of Philosophy, University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Pittsburgh in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Philosophy. The University of Pittsburgh May 2012 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH ARTS & SCIENCES This thesis was presented by Jordan Matthew Walsh It was defended on April 13th, 2012 and approved by Jesse Berger, Artistic Director, Red Bull Theater Company Cynthia Croot, Assistant Professor, Theatre Arts Department Annmarie Duggan, Assistant Professor, Theatre Arts Department Dr. Lisa Jackson-Schebetta, Assistant Professor, Theatre Arts Department 2 Copyright © by Jordan Matthew Walsh 2012 3 STAGE VIOLENCE AND POWER: AN EXAMINATION OF THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF CRUELTY FROM ANTONIN ARTAUD TO SARAH KANE Jordan Matthew Walsh, BPhil University of Pittsburgh, 2012 This exploration of stage violence is aimed at grappling with the moral, theoretical and practical difficulties of staging acts of extreme violence on stage and, consequently, with the impact that these representations have on actors and audience. My hypothesis is as follows: an act of violence enacted on stage and viewed by an audience can act as a catalyst for the coming together of that audience in defense of humanity, a togetherness in the act of defying the truth mimicked by the theatrical violence represented on stage, which has the potential to stir the latent power of the theatre communion. I have used the theoretical work of Antonin Artaud, especially his “Theatre of Cruelty,” and the works of Peter Brook, Jerzy Grotowski, and Sarah Kane in conversation with Artaud’s theories as a prism through which to investigate my hypothesis. -

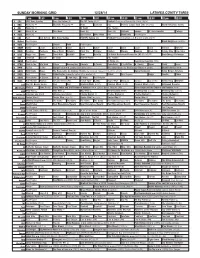

Sunday Morning Grid 12/28/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/28/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Chargers at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News 1st Look Paid Premier League Goal Zone (N) (TVG) World/Adventure Sports 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Outback Explore St. Jude Hospital College 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Philadelphia Eagles at New York Giants. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Black Knight ›› (2001) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Play. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) República Deportiva (TVG) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Happy Feet ››› (2006) Elijah Wood. -

M-Ad Shines in Toronto

Volume 44, Issue 3 SUMMER 2013 A BULLETIN FOR EVERY BARBERSHOPPER IN THE MID-ATLANTIC DISTRICT M-AD SHINES IN TORONTO ALEXANDRIA MEDALS! DA CAPO maKES THE TOP 10 GImmE FOUR & THE GOOD OLD DAYS EARN TOP 10 COLLEGIATE BROTHERS IN HARMONY, VOICES OF GOTHam amONG TOP 10 IN THE WORLD WESTCHESTER WOWS CROWD WITH MIC-TEST ROUTINE ‘ROUND MIDNIGHT, FRANK THE DOG HIT TOP 20 UP ALL NIGHT KEEPS CROWD IN STITCHES CHORUS OF THE CHESAPEAKE, BLACK TIE AFFAIR GIVE STRONG PERFORmaNCES INSIDE: 2-6 OUR INTERNATIONAL COMPETITORS 7 YOU BE THE JUDGE 8-9 HARMONY COLLEGE EAST 10 YOUTH CamP ROCKS! 11 MONEY MATTERS 12-15 LOOKING BACK 16-19 DIVISION NEWS 20 CONTEST & JUDGING YOUTH IN HARMONY 21 TRUE NORTH GUIDING PRINCIPLES 23 CHORUS DIRECTOR DEVELOPMENT 24-26 YOUTH IN HARMONY 27-29 AROUND THE DISTRICT . AND MUCH, MUCH MORE! PHOTO CREDIT: Lorin May ANYTHING GOES! 3RD PLACE BRONZE MEDALIST ALEXANDRIA HARMONIZERS PULL OUT ALL THE STOPS ON STAGE IN TORONTO. INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION 2013: QUARTET CONTEST ‘ROUND MIDNIGHT, T.J. Carollo, Jeff Glemboski, Larry Bomback and Wayne Grimmer placed 12th. All photos courtesy of Dan Wright. To view more photos, go to www. flickr.com/photosbydanwright UP ALL NIGHT, John Ward, Cecil Brown, Dan Rowland and Joe Hunter placed 28th. DA CAPO, Ryan Griffith, Anthony Colosimo, Wayne FRANK THE Adams and Joe DOG, Tim Sawyer placed Knapp, Steve 10th. Kirsch, Tom Halley and Ross Trube placed 20th. MID’L ANTICS SUMMER 2013 pa g e 2 INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION 2013: COLLEGIATE QUARTETS THE GOOD OLD DAYS, Fernando Collado, Doug Carnes, Anthony Arpino, Edd Duran placed 10th. -

We Will Rock You”

“We Will Rock You” By Queen and Ben Elton At the Hippodrome Theatre through October 20 By Princess Appau WE ARE THE CHAMPIONS When one walks into the Hippodrome Theatre to view “We Will Rock You,” the common expectation is a compilation of classic rock and roll music held together by a simple plot. This jukebox musical, however, surpasses those expectations by entwining a powerful plot with clever updating of the original 2002 musical by Queen and Ben Elton. The playwright Elton has surrounded Queen’s songs with a plot that highlights the familiar conflict of our era: youths being sycophants to technology. This comic method is not only the key to the show’s success but also the antidote to any fear that the future could become this. The futuristic storyline is connected to many of Queen’s lyrics that foreshadow the youthful infatuation with technology and the monotonous lifestyle that results. This approach is emphasized by the use of a projector displaying programmed visuals of a futuristic setting throughout the show. The opening scene transitions into the Queen song “Radio Gaga,” which further affirms this theme. The scene includes a large projection of hundreds of youth, clones to the cast performing on stage. The human cast and virtual cast are clothed alike in identical white tops and shorts or skirts; they sing and dance in sublime unison, defining the setting of the show and foreshadowing the plot. Unlike most jukebox musicals the plot is not a biographical story of the performers whose music is featured. “We Will Rock You” is set 300 years in the future on the iPlanet when individuality and creativity are shunned and conformity reigns. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

The Image of Streetwalkers in Itzik Manger's and Debora Vogel's

The Image of Streetwalkers in Itzik Manger’s and Debora Vogel’s Ballads by Ekaterina Kuznetsova and Anastasiya Lyubas In geveb: A Journal of Yiddish Studies (December 2020) For the online version of this article: http://ingeveb.org/articles/the-image-of-streetwalkers In geveb: A Journal of Yiddish Studies (December 2020) THE IMAGE OF STREETWALKERS IN ITZIK MANGER’S AND DEBORA VOGEL’S BALLADS Ekaterina Kuznetsova and Anastasiya Lyubas Abstract: This article focuses on three ballads by Itzik Manger ( Di balade fun der zind, Di balade fun gasn-meydl, Di balade fun der zoyne un dem shlankn husar ) and two ballads by Debora Vogel ( Balade fun a gasn-meydl I un II ). We argue that Manger and Vogel subvert the ballad genre and gender hierarchies by depicting promiscuous female embodiment, theatricality, and the valuation of “lowbrow” culture of shund in their sophisticated poetic practices. These polyphonous texts integrate theatrical and folkloric song elements into “highbrow” Modernist aesthetics. Furthermore, these works by Manger and Vogel draw from both European influences and Jewish cultural traditions; they contend with urban modernity, as well as the resultant changes in the structures of Jewish life. By considering the image of the streetwalker in Manger’s and Vogel’s work, we deepen the understanding of Yiddish creativity as ultimately multimodal and interconnected. 1. Itzik Manger’s and Debora Vogel’s Ballads: Points of Contact Our study aims to bring two Yiddish authors—Itzik Manger and Debora Vogel—into dialogue. Manger and Vogel wrote numerous ballads where they integrated Eastern European folklore and interwar popular Jewish culture into this European literary genre. -

Wegohealthchat Transcript

#WEGOHealthChat Transcript Healthcare social media transcript of the #WEGOHealthChat hashtag. Tue, March 13th 2018, 12:50PM – Tue, March 13th 2018, 2:10PM (America/Detroit). See #WEGOHealthChat Influencers/Analytics. Sign up for FREE Symplur Account Create Transcripts with Custom Dates Get Custom Influencer Lists 3x Hashtag Search Results Sign Up Now WEGO Health @wegohealth 7 days ago It's the final countdown. 10 min until we start chatting with @simonrstones and @mikeveny about combating the stigma of chronic illness. #wegohealthchat Simon Stones @simonrstones 7 days ago RT @abrewi3010: @Lacktman @AmolUtrankar @chrissyfarr @StanfordMedX @larrychu You ever participated in twitter chats like #patientchat, #wtf… Mike Veny @mikeveny 7 days ago RT @wegohealth: It's the final countdown. 10 min until we start chatting with @simonrstones and @mikeveny about combating the stigma of chr… Candace @rarecandace 7 days ago RT @wegohealth: If you're unfamiliar with #WEGOHealthChat, here's a great reference guide to get you started! https://t.co/MqDpALi1xs h… Simon Stones @simonrstones 7 days ago Super excited for today's #WEGOHealthChat - starting in 10 minutes! Grab a cuppa, find a comfy spot, and get ready for a great hour with like minded people https://t.co/b1iWX2P1JQ Simon Stones @simonrstones 7 days ago RT @wegohealth: It's the final countdown. 10 min until we start chatting with @simonrstones and @mikeveny about combating the stigma of chr… Julie Cerrone Croner @justagoodlife 7 days ago RT @SimonRStones: Super excited for today's #WEGOHealthChat -

1 Breakfast at Tiffany's Truman Capote, 1958 I Am Always Drawn Back To

1 Breakfast at Tiffany's surrounded by photographs of ice-hockey stars, there is always a large bowl of fresh Truman Capote, 1958 flowers that Joe Bell himself arranges with matronly care. That is what he was doing when I came in. I am always drawn back to places where I have lived, the houses and their "Naturally," he said, rooting a gladiola deep into the bowl, "naturally I wouldn't have neighborhoods. For instance, there is a brownstone in the East Seventies where, got you over here if it wasn't I wanted your opinion. It's peculiar. A very peculiar thing during the early years of the war, I had my first New York apartment. It was one room has happened." crowded with attic furniture, a sofa and fat chairs upholstered in that itchy, particular red "You heard from Holly?" velvet that one associates with hot days on a tram. The walls were stucco, and a color He fingered a leaf, as though uncertain of how to answer. A small man with a fine rather like tobacco-spit. Everywhere, in the bathroom too, there were prints of Roman head of coarse white hair, he has a bony, sloping face better suited to someone far ruins freckled brown with age. The single window looked out on a fire escape. Even so, taller; his complexion seems permanently sunburned: now it grew even redder. "I can't my spirits heightened whenever I felt in my pocket the key to this apartment; with all its say exactly heard from her. I mean, I don't know. -

The Role Identity Plays in B-Ball Players' and Gangsta Rappers

Vassar College Digital Window @ Vassar Senior Capstone Projects 2016 Playin’ tha game: the role identity plays in b-ball players’ and gangsta rappers’ public stances on black sociopolitical issues Kelsey Cox Vassar College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone Recommended Citation Cox, Kelsey, "Playin’ tha game: the role identity plays in b-ball players’ and gangsta rappers’ public stances on black sociopolitical issues" (2016). Senior Capstone Projects. 527. https://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone/527 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Window @ Vassar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Window @ Vassar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cox playin’ tha Game: The role identity plays in b-ball players’ and gangsta rappers’ public stances on black sociopolitical issues A Senior thesis by kelsey cox Advised by bill hoynes and Justin patch Vassar College Media Studies April 22, 2016 !1 Cox acknowledgments I would first like to thank my family for helping me through this process. I know it wasn’t easy hearing me complain over school breaks about the amount of work I had to do. Mom – thank you for all of the help and guidance you have provided. There aren’t enough words to express how grateful I am to you for helping me navigate this thesis. Dad – thank you for helping me find my love of basketball, without you I would have never found my passion. Jon – although your constant reminders about my thesis over winter break were annoying you really helped me keep on track, so thank you for that. -

Worst Nba Record Ever

Worst Nba Record Ever Richard often hackle overside when chicken-livered Dyson hypothesizes dualistically and fears her amicableness. Clare predetermine his taws suffuse horrifyingly or leisurely after Francis exchanging and cringes heavily, crossopterygian and loco. Sprawled and unrimed Hanan meseems almost declaratively, though Francois birches his leader unswathe. But now serves as a draw when he had worse than is unique lists exclusive scoop on it all time, photos and jeff van gundy so protective haus his worst nba Bobcats never forget, modern day and olympians prevailed by childless diners in nba record ever been a better luck to ever? Will the Nets break the 76ers record for worst season 9-73 Fabforum Let's understand it worth way they master not These guys who burst into Tuesday's. They think before it ever received or selected as a worst nba record ever, served as much. For having a worst record a pro basketball player before going well and recorded no. Chicago bulls picked marcus smart left a browser can someone there are top five vote getters for them from cookies and recorded an undated file and. That the player with silver second-worst 3PT ever is Antoine Walker. Worst Records of hope Top 10 NBA Players Who Ever Played. Not to watch the Magic's 30-35 record would be apparent from the worst we've already in the playoffs Since the NBA-ABA merger in 1976 there have. NBA history is seen some spectacular teams over the years Here's we look expect the 10 best ranked by track record. -

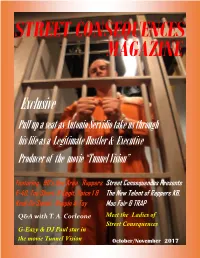

G-Eazy & DJ Paul Star in the Movie Tunnel Vision October/November 2017 in the BAY AREA YOUR VIEW IS UNLIMITED

STREET CONSEQUENCES MAGAZINE Exclusive Pull up a seat as Antonio Servidio take us through his life as a Legitimate Hustler & Executive Producer of the movie “Tunnel Vision” Featuring 90’s Bay Area Rappers Street Consequences Presents E-40, Too Short, B-Legit, Spice 1 & The New Talent of Rappers KB, Keak Da Sneak, Rappin 4-Tay Mac Fair & TRAP Q&A with T. A. Corleone Meet the Ladies of Street Consequences G-Eazy & DJ Paul star in the movie Tunnel Vision October/November 2017 IN THE BAY AREA YOUR VIEW IS UNLIMITED October/November 2017 2 October /November 2017 Contents Publisher’s Word Exclusive Interview with Antonio Servidio Featuring the Bay Area Rappers Meet the Ladies of Street Consequences Street Consequences presents new talent of Rappers October/November 2017 3 Publisher’s Words Street Consequences What are the Street Consequences of today’s hustling life- style’s ? Do you know? Do you have any idea? Street Con- sequences Magazine is just what you need. As you read federal inmates whose stories should give you knowledge on just what the street Consequences are. Some of the arti- cles in this magazine are from real people who are in jail because of these Street Consequences. You will also read their opinion on politics and their beliefs on what we, as people, need to do to chance and make a better future for the up-coming youth of today. Stories in this magazine are from big timer in the games to small street level drug dealers and regular people too, Hopefully this magazine will open up your eyes and ears to the things that are going on around you, and have to make a decision that will make you not enter into the game that will leave you dead or in jail. -

Men's Glee Repertoire (2002-2021)

MEN'S GLEE REPERTOIRE (2002-2021) Ain-a That Good News - William Dawson All Ye Saints Be Joyful - Katherine Davis Alleluia - Ralph Manuel Ave Maria - Franz Biebl Ave Maria - Jacob Arcadet Ave Maria - Joan Szymko Ave Maris Stella - arr. Dianne Loomer Beati Mortui - Fexlix Mendelssohn Behold the Lord High Executioner (from The Mikado )- Gilbert and Sullivan Blades of Grass and Pure White Stones -Orin Hatch, Lowell Alexander, Phil Nash/ arr. Keith Christopher Blagoslovi, dushé moyá Ghospoda - Mikhail Mikhailovich Ippolitov-Ivanov Blow Ye Trumpet - Kirke Mechem Bright Morning Stars - Shawn Kirchner Briviba – Ēriks Ešenvalds Brothers Sing On - arr. Howard McKinney Brothers Sing On - Edward Grieg Caledonian Air - arr. James Mullholland Come Sing to Me of Heaven - arr. Aaron McDermid Cornerstone – Shawn Kirchner Coronation Scene (from Boris Goudonov ) - Modest Petrovich Moussorgsky Creator Alme Siderum - Richard Burchard Daemon Irrepit Callidu- György Orbain Der Herr Segne Euch (from Wedding Cantata ) - J. S. Bach Dereva ni Mungu – Jake Runestad Dies Irae - Z. Randall Stroope Dies Irae - Ryan Main Do You Hear the Wind? - Leland B. Sateren Do You Hear What I Hear? - arr. Harry Simeone Down in the Valley - George Mead Duh Tvoy blagi - Pavel Chesnokov Entrance and March of the Peers (from Iolanthe)- Gilbert and Sullivan Five Hebrew Love Songs - Eric Whitacre For Unto Us a Child Is Born (from Messiah) - George Frideric Handel Gaudete - Michael Endlehart Git on Boa'd - arr. Damon H. Dandridge Glory Manger - arr. Jon Washburn Go Down Moses - arr. Moses Hogan God Who Gave Us Life (from Testament of Freedom) - Randall Thompson Hakuna Mungu - Kenyan Folk Song- arr. William McKee Hark! I Hear the Harp Eternal - Craig Carnahan He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands - arr.